Back in 2013, the Hayward Gallery held an exhibition simply called Light Show. I was in my first year of university and that exhibition was one of my earliest experiences of installation art en masse. Still to this day, I can vividly remember how mind blown I was experiencing Anthony McCall’s ‘light sculptures’ in a pitch black room, by far my favourite works in that show.

Fast forward 11 years later, I got to relive that encounter once more, this time in a concentrated survey of the artist’s work at Tate Modern. McCall specialises in light projections, which doesn’t sound like much at first…until you enter them.

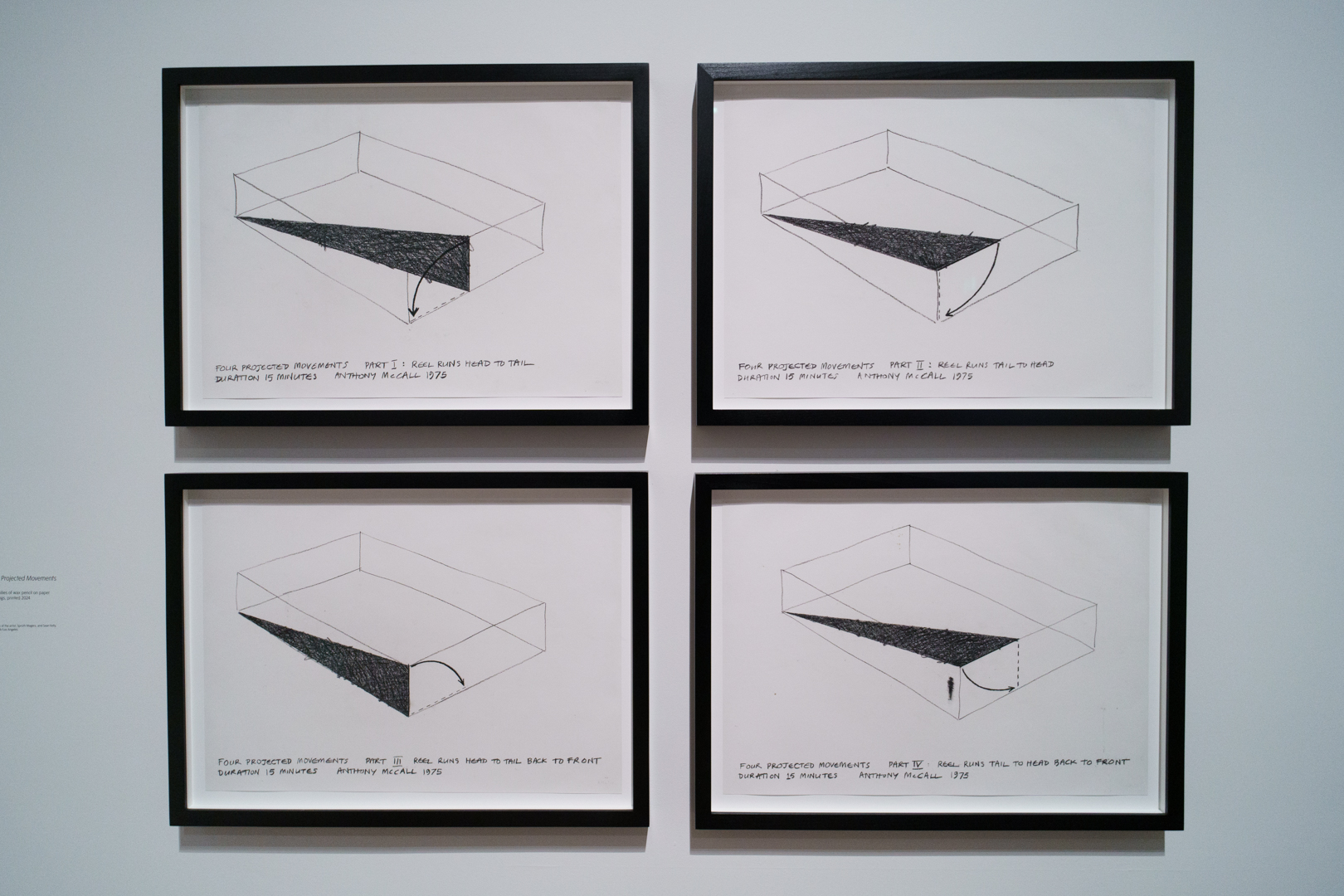

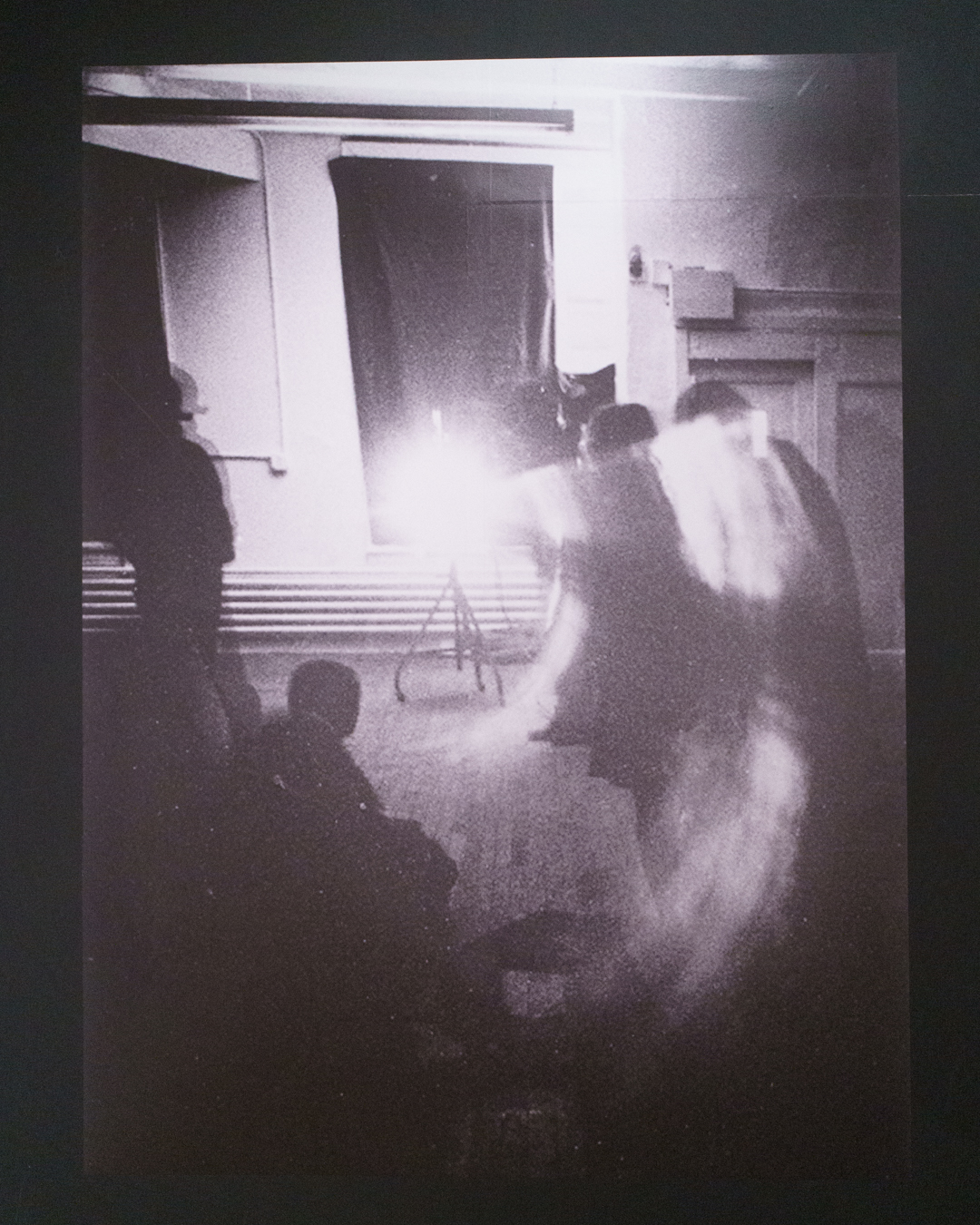

A small, slightly underwhelming introductory room gives viewers a basic sense of McCall’s process, including a sketchbook, facsimiles of preparatory drawings, and photographs. Grounded in mathematics, his projections are based on algorithmic equations. Sounds boring, I know, but I promise this is worth it.

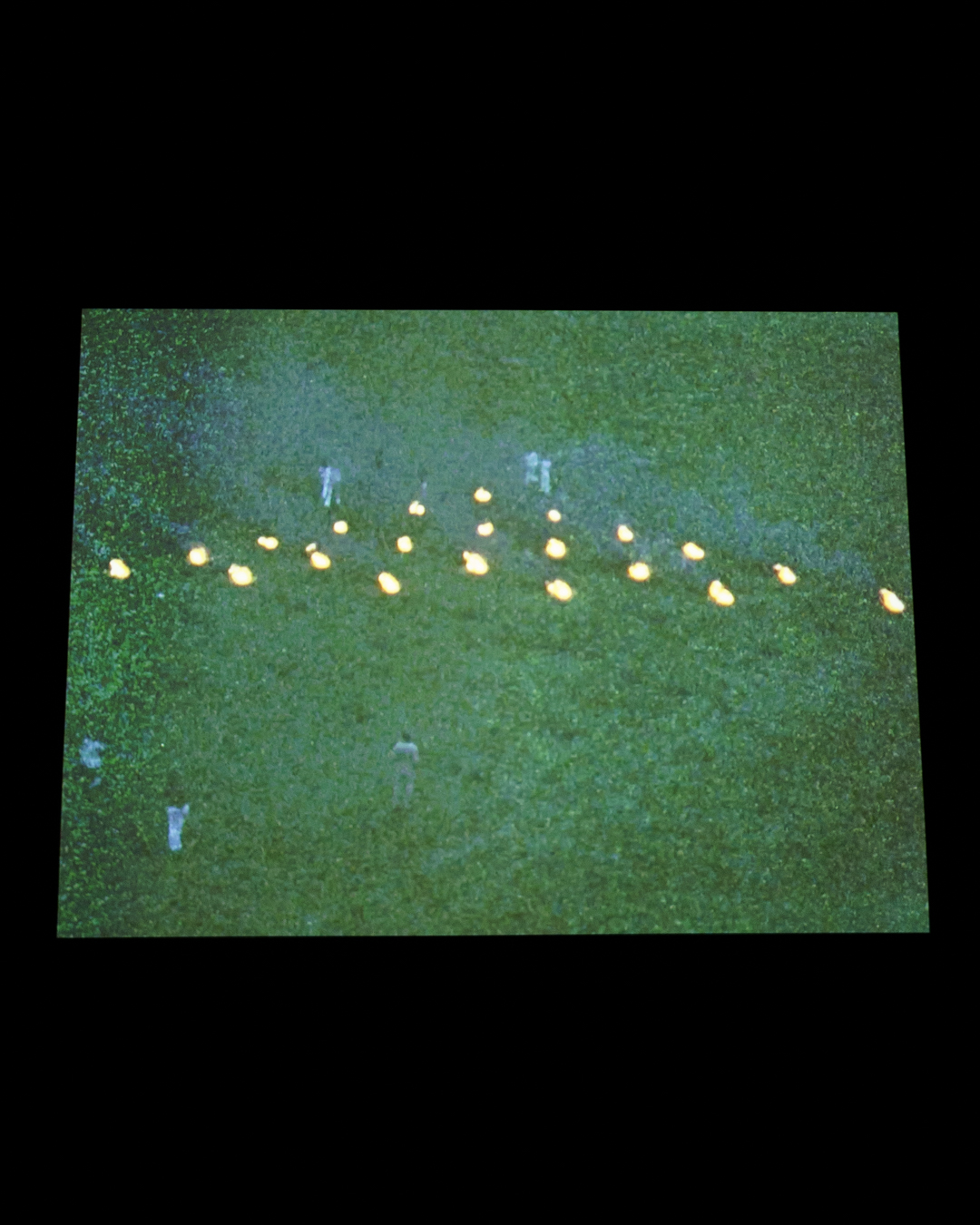

The second room is a screening of one of his earliest films, Landscape for Fire (1973), which shows McCall lighting small fires at dusk in a geometric grid with the British artist collective Exit. Honestly, it felt rather out of place from the rest of the exhibition.

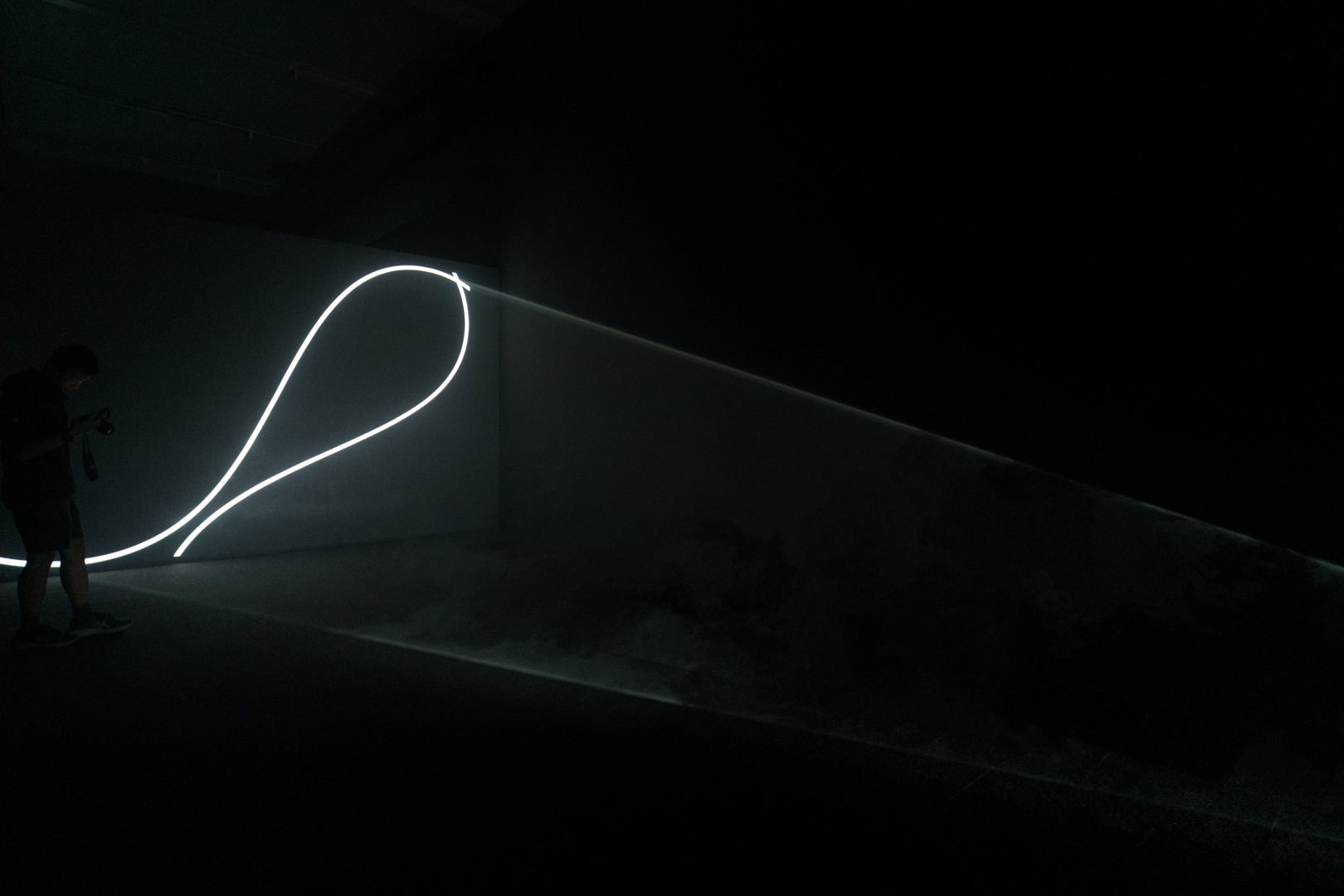

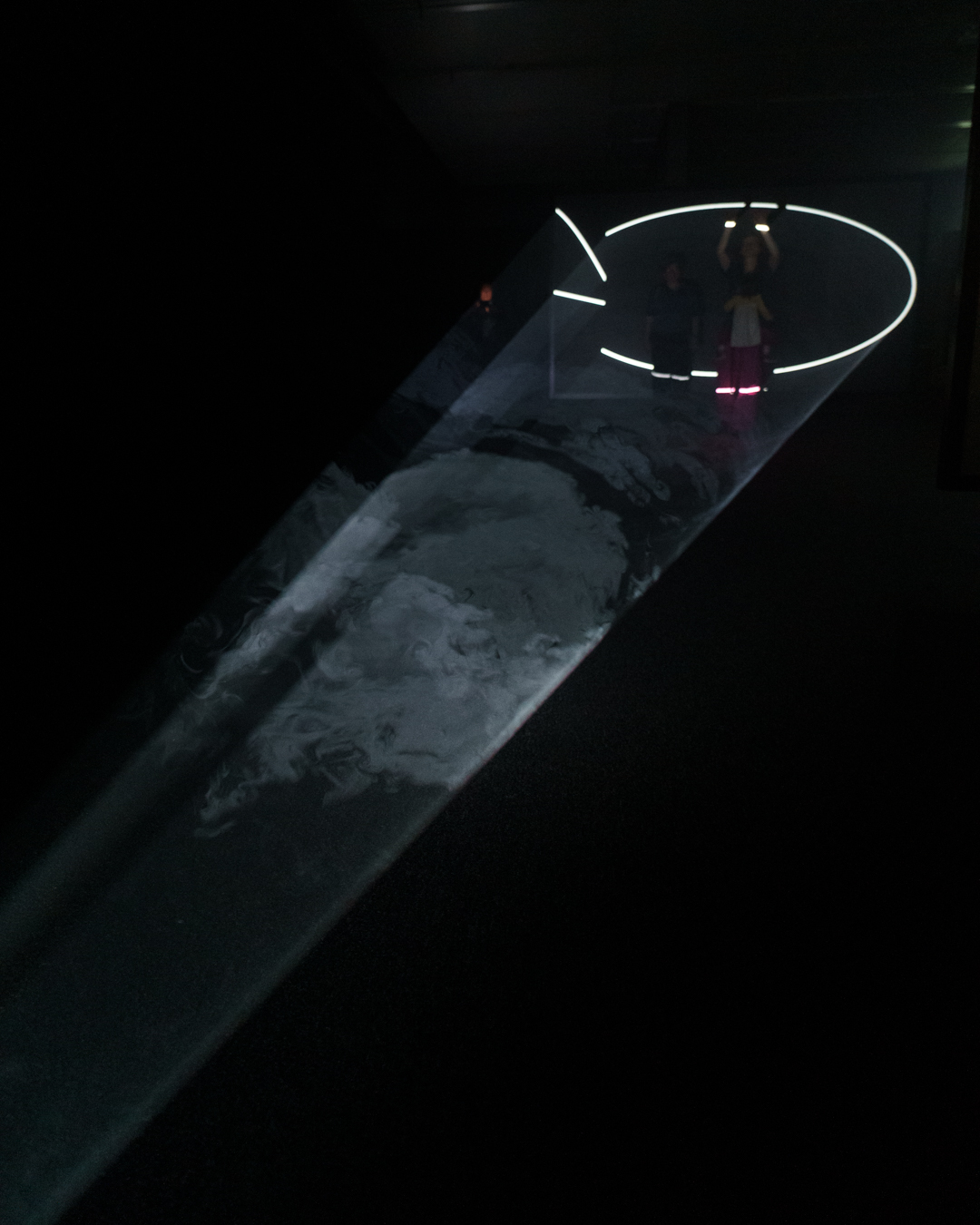

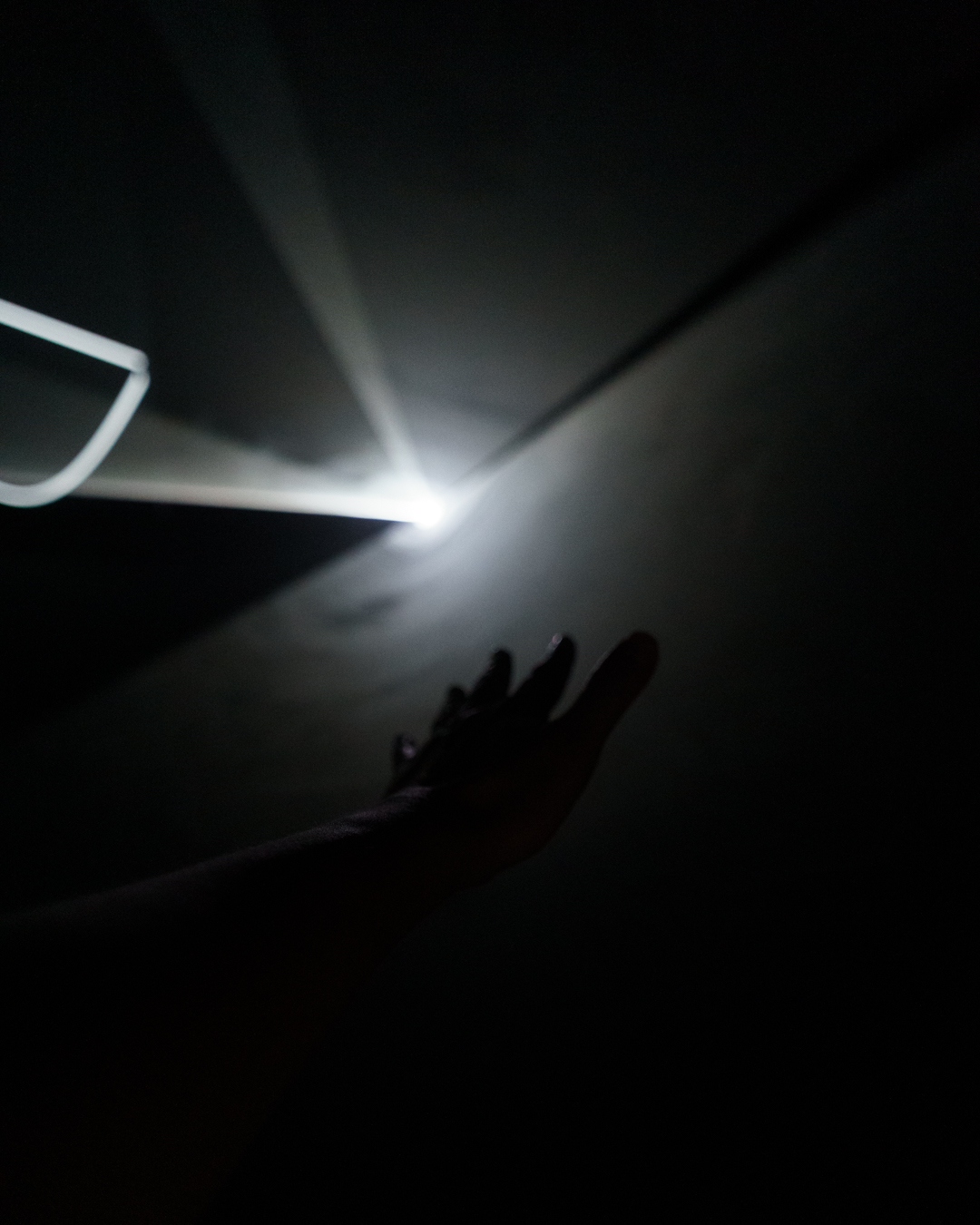

After these filler rooms, one arrives at the pièce de résistance: four light projections permeating a dark, mist-filled room. These span from his very first light installation – Line Describing a Cone (1973) – to the more recent Split-Second (Mirror) I (2018). It’s actually a great place for people-watching. No one knows how to interact with these pieces ‘correctly’, so everyone hesitantly extends their hands into the works while their friends snap aesthetic pictures for their social media profiles. Seeing how one’s fingers interrupt the perfect path of the light is certainly a cool, pleasing effect that can entertain children and adults for hours.

The power of these simple projections unveils itself when you walk into them, letting their curvilinear forms surround you completely. The experience is mystical, entrancing, and weirdly soothing if you face the light source directly. If you’re lucky to be obstructed by other visitors during Face to Face IV (2013), you receive a cinematic view of discombobulated heads in shadow, appearing like souls about to head into Heaven’s light while a white, wispy haze envelopes them.

These projections are not static, however. With a little patience, you can see the physical shape and gradual movement of each waveform on the wall behind each piece. As such, the boundaries of the light moves incrementally in physical space. This causes some very quirky visual effects if you wait long enough.

I can’t speak for claustrophobics, but taller works like Doubling Back (2003) can evoke the feeling of being in an enclosed space. I like to refer to these boundaries of light as ‘walls’. Despite literally being a trick of the light, those walls can reasonably be perceived as solid surfaces.

Where a waveform intersects with itself, the illusion can appear like physical shelves. It was incredibly tempting to rest my hand on a horizontal ‘surface’ or even place my phone on it. Such is the power of simple trickery, which it genuinely is. The set up could probably be done at home with a projector and a fog machine. Yet the aesthetic experience is so great.

On the flip side, I can also forsee people missing the point entirely. The lack of spectacle might be disappointing to less experienced visitors, while others might treat it as a family-friendly activity.

This is by no means a perfect exhibition, and the ‘less is more’ concept doesn’t always translate in this modern age of decreasing attention spans. But I think McCall’s artworks speak for themselves very well if people are willing to play around with them for more than a couple minutes.

Anthony McCall: Solid Light (27 June 2024 – 27 April 2025) is at Tate Modern, London, https://www.tate.org.uk/

Leave a comment