Michelangelo and Beyond is not a Michelangelo exhibition. Instead, it is a transhistorical survey of the nude throughout Western art from the Renaissance to the Vienna Secession, and quite an accessible one at that.

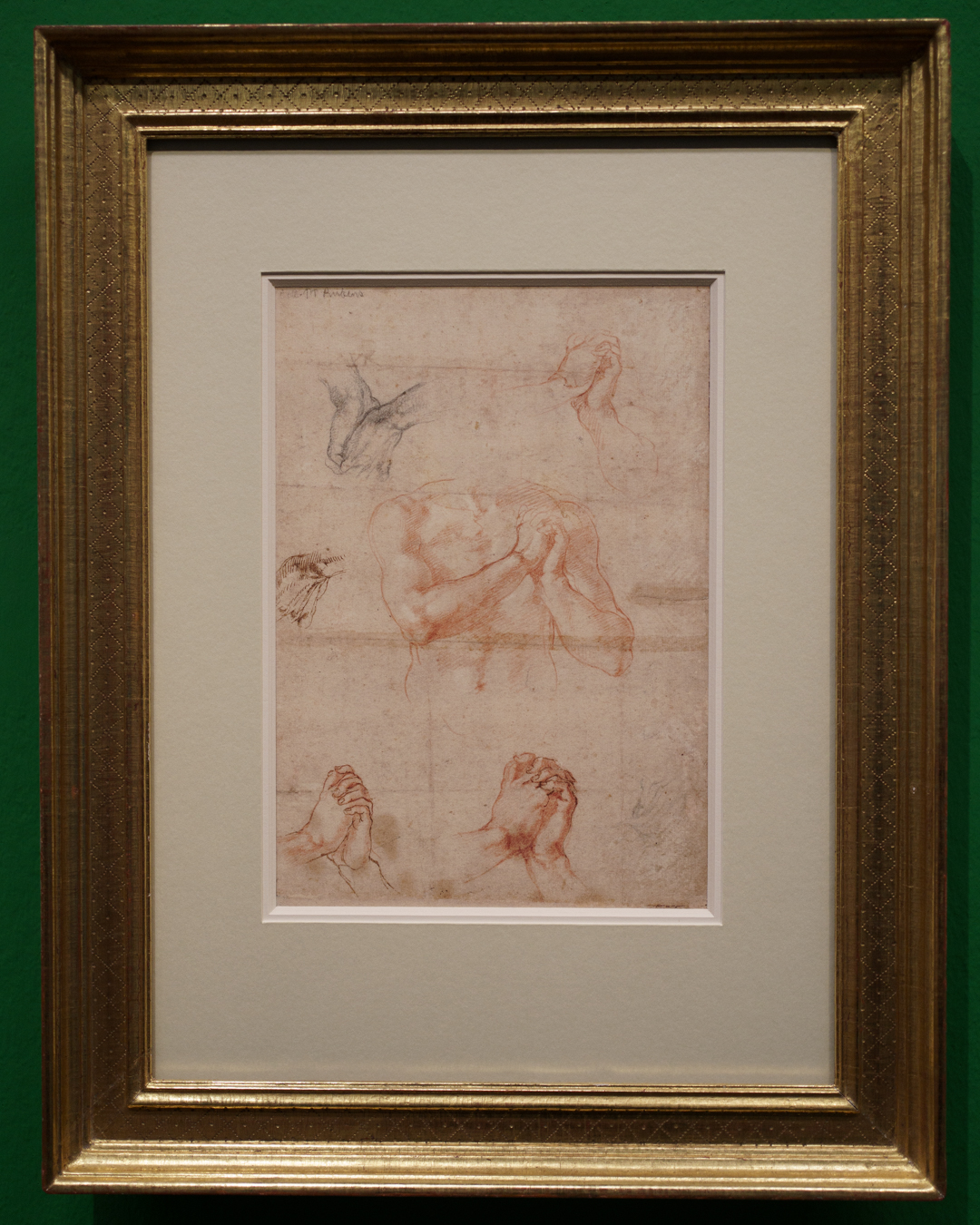

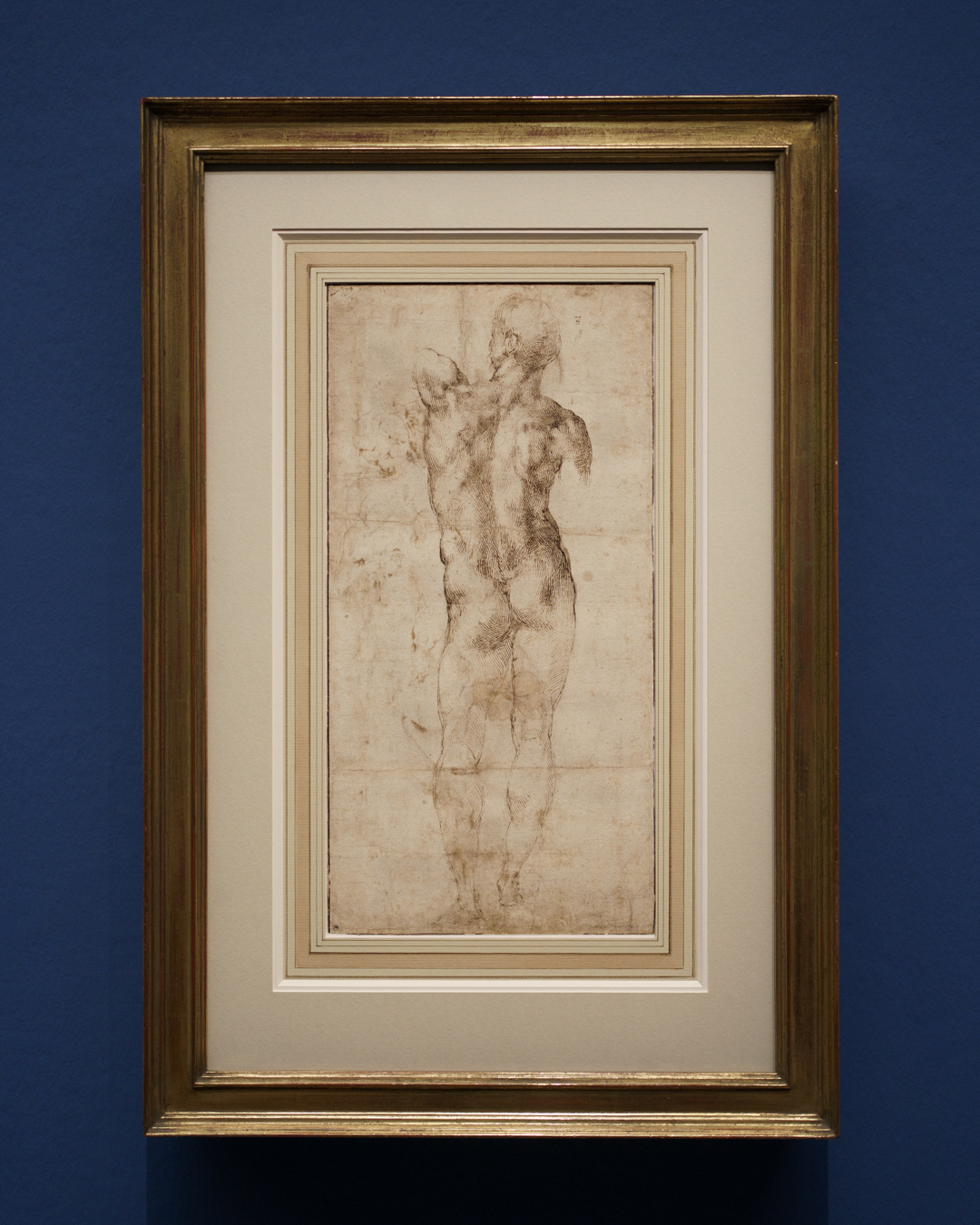

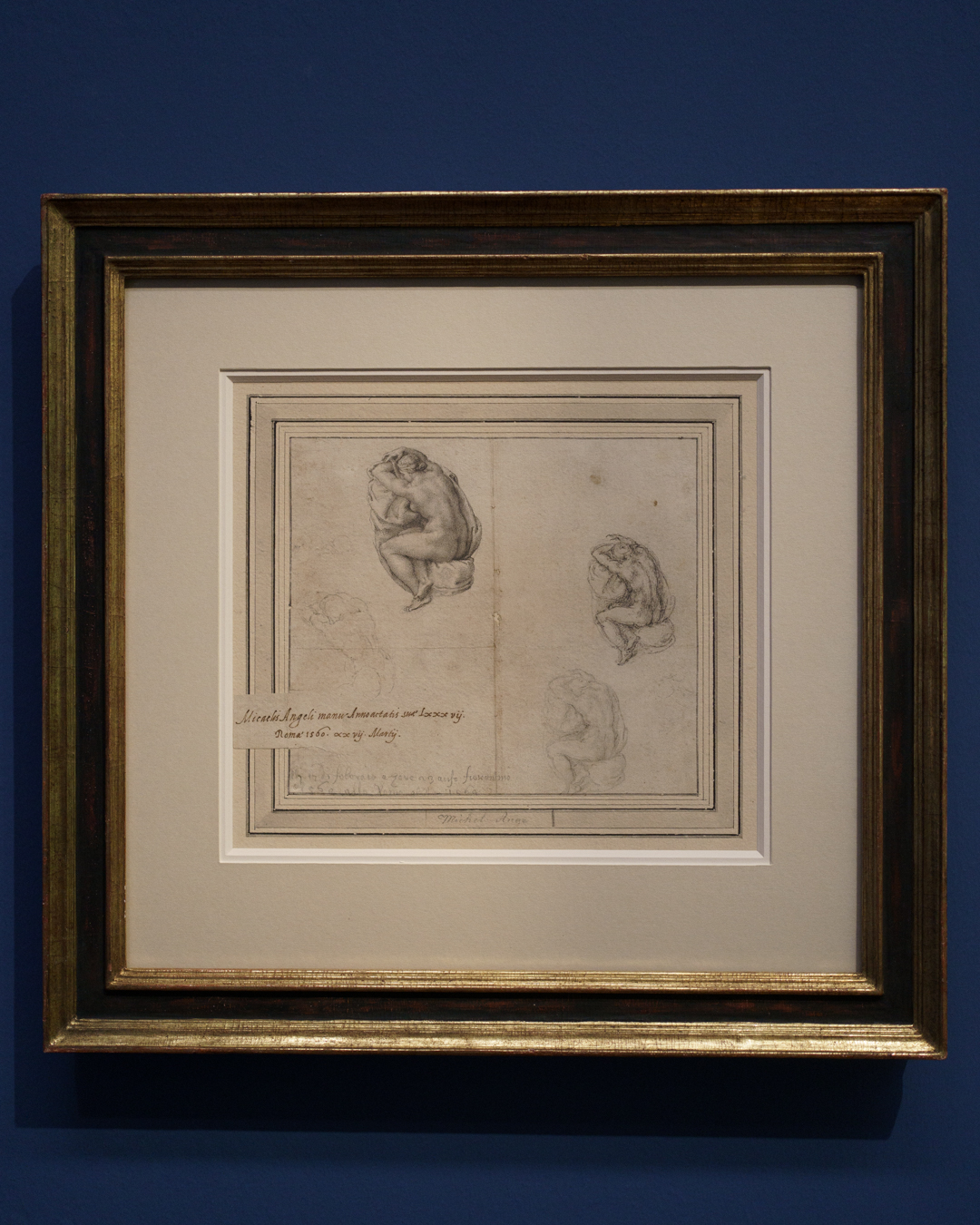

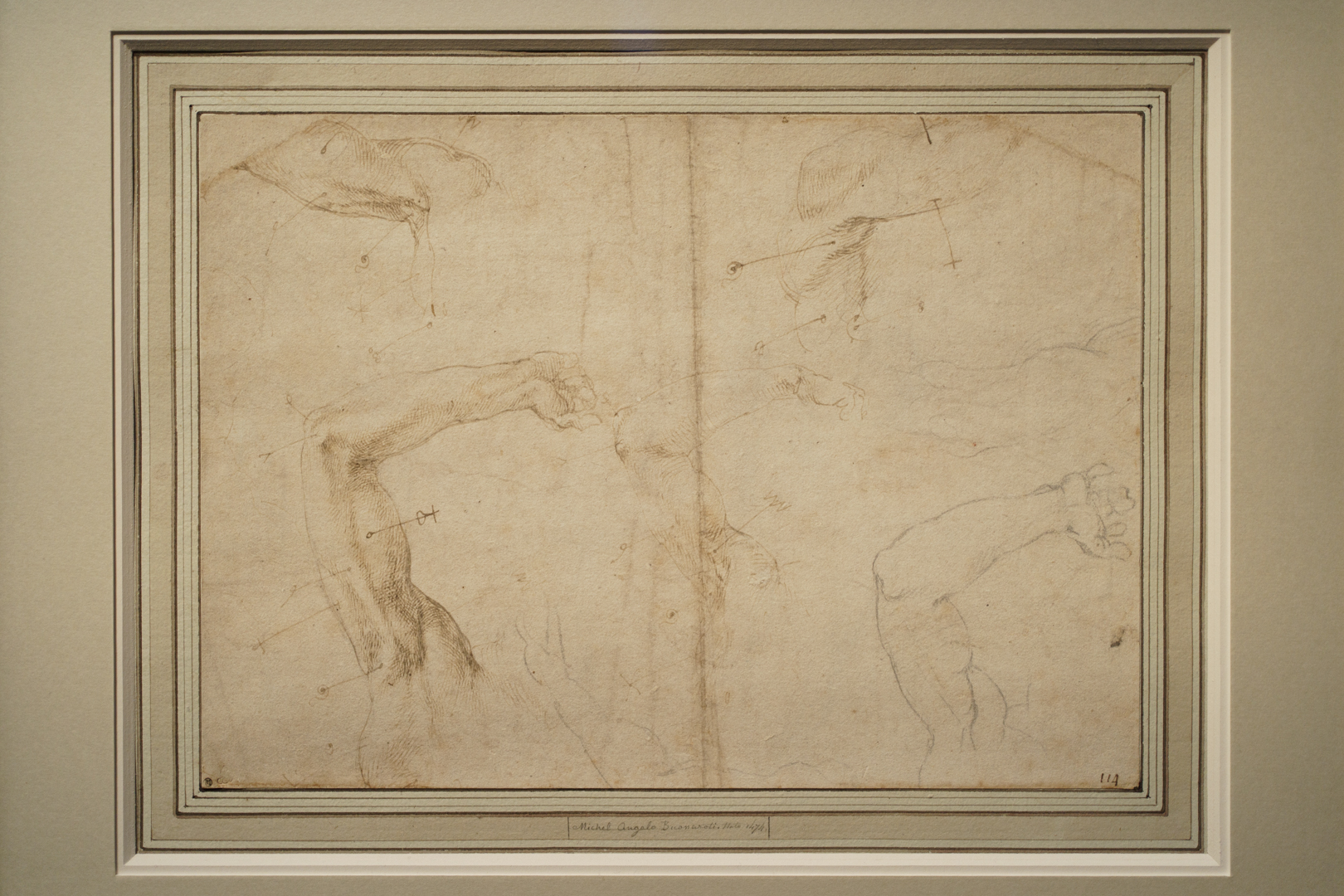

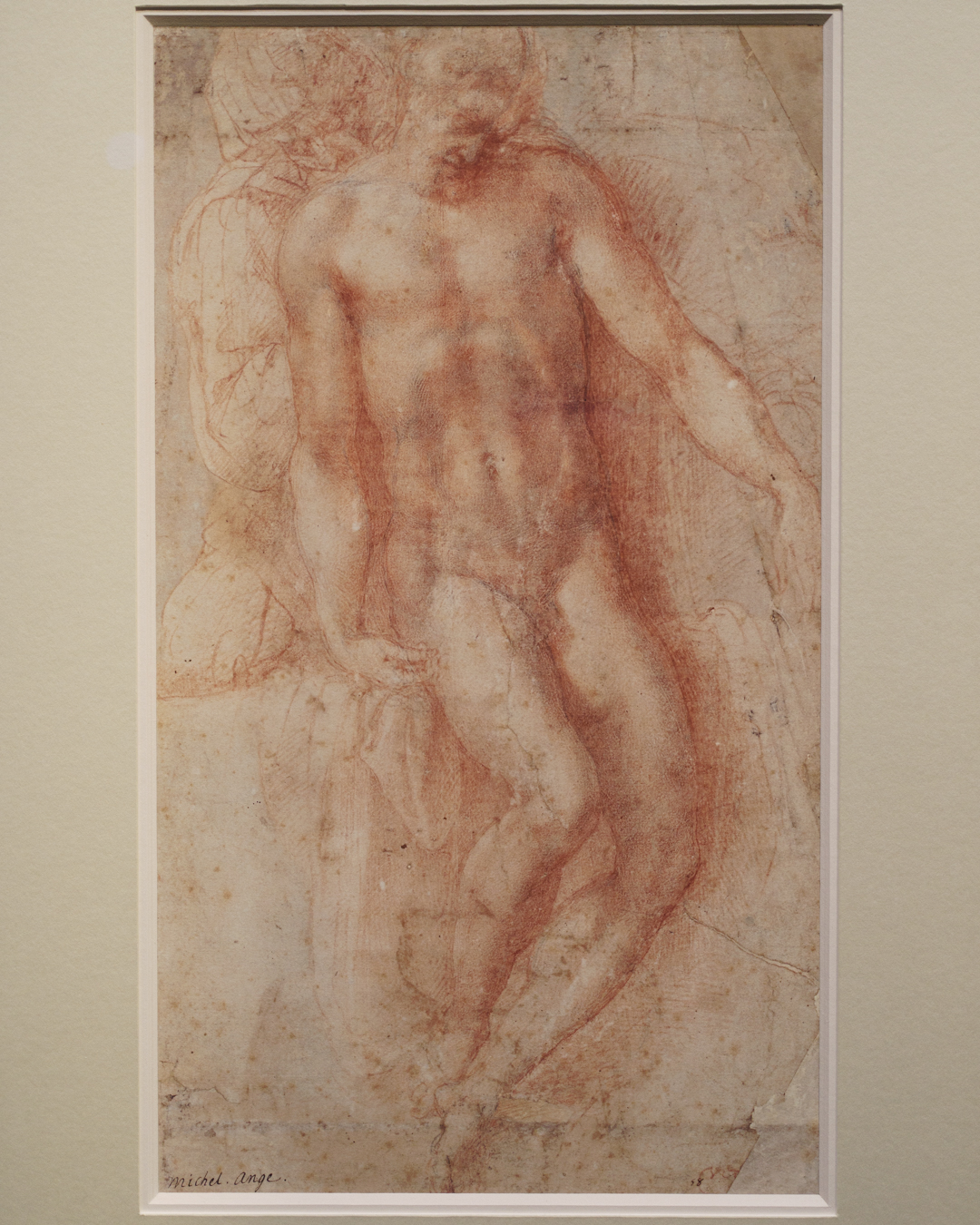

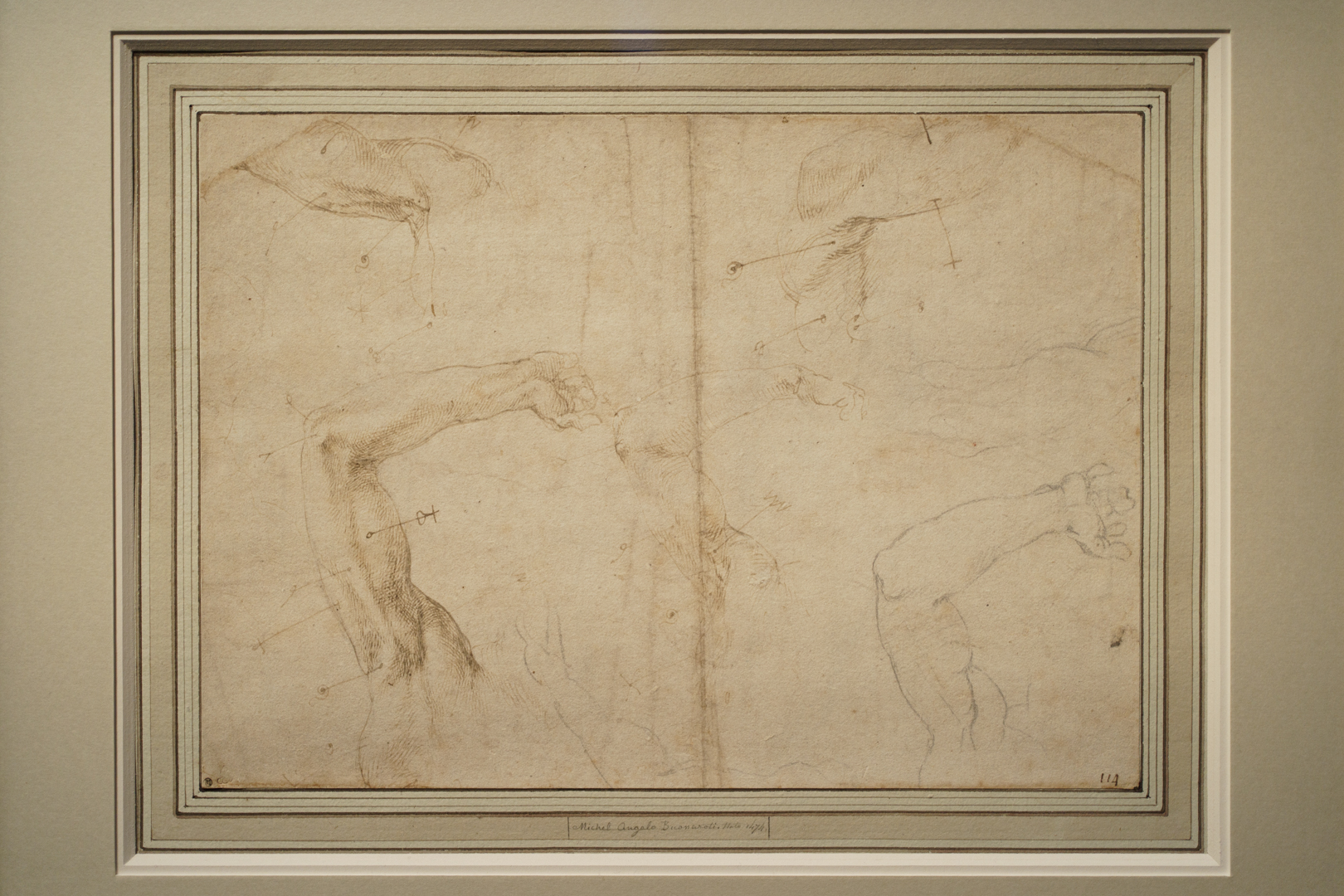

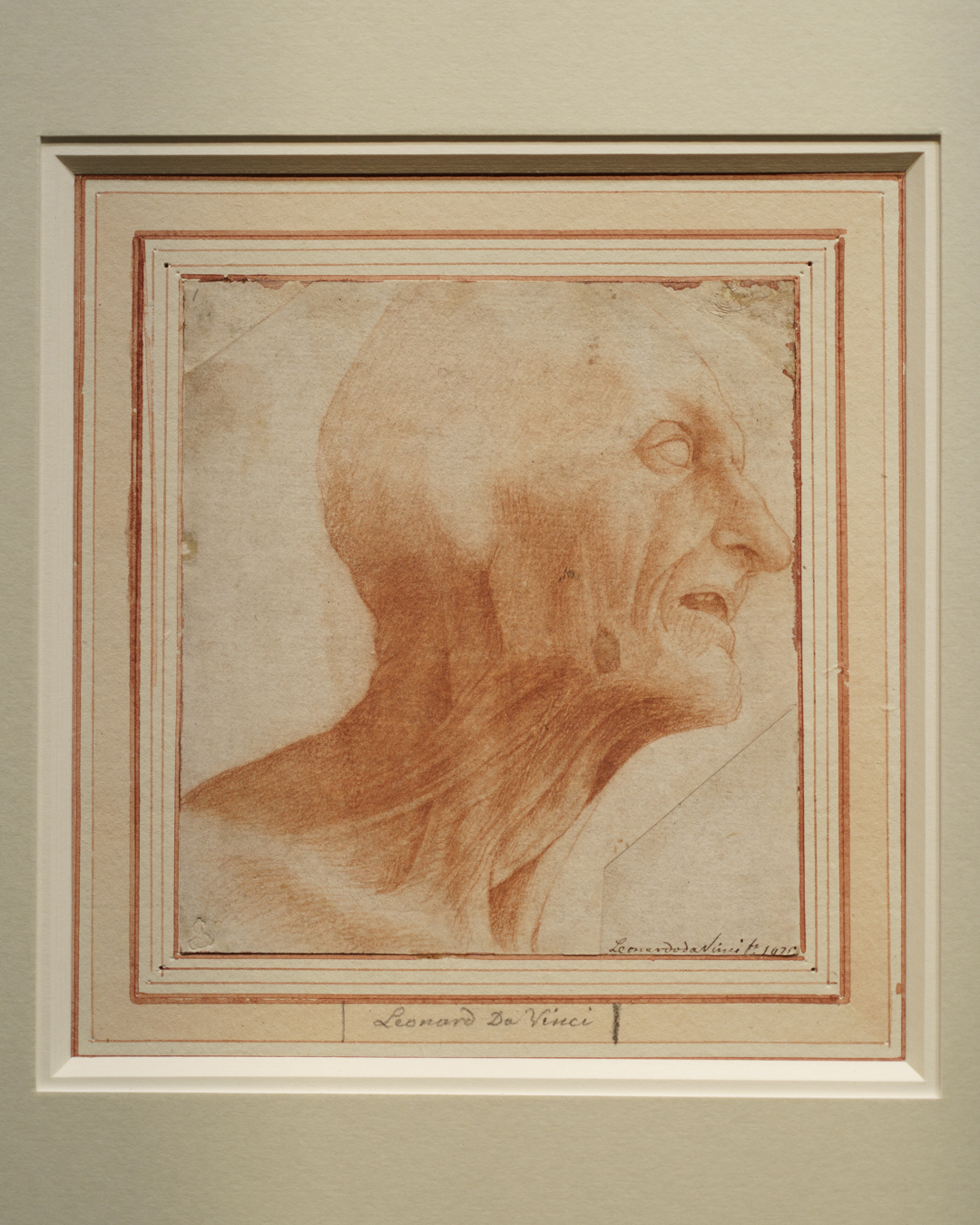

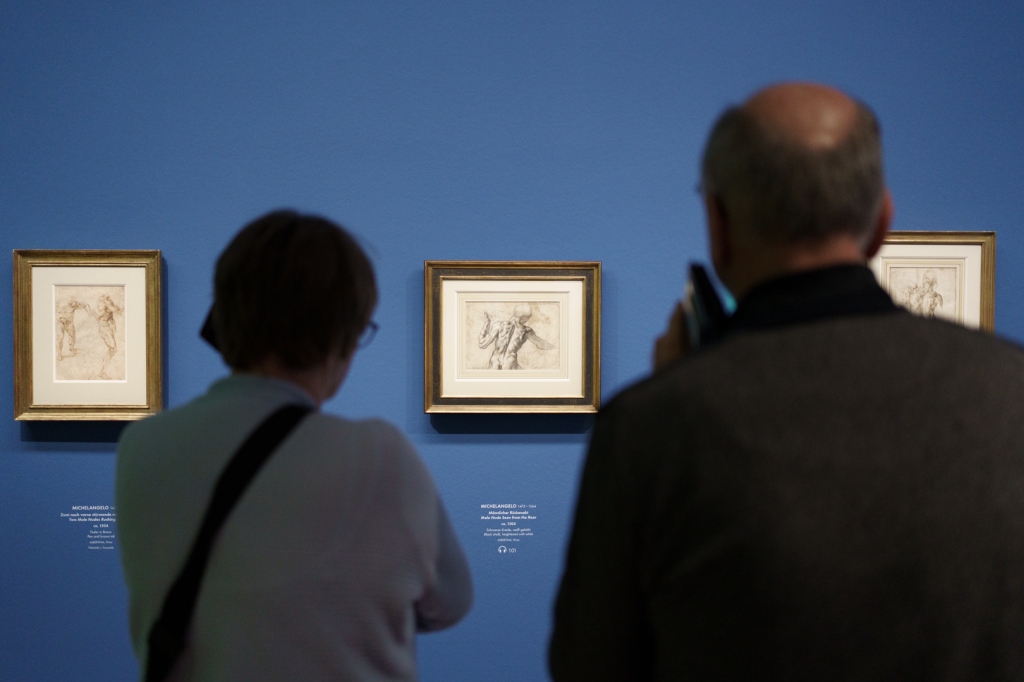

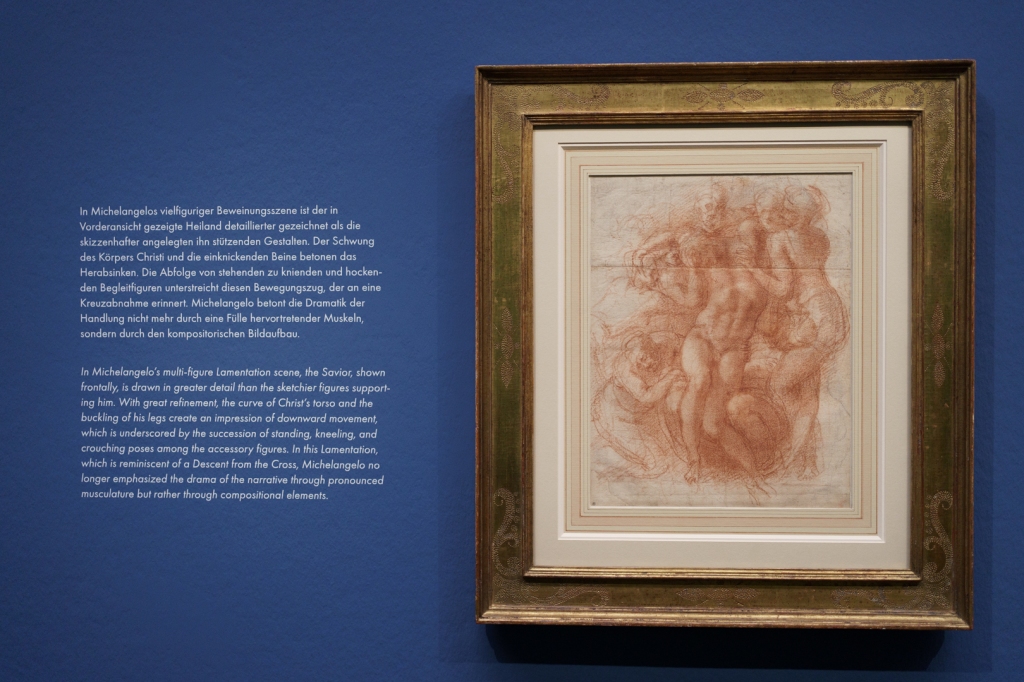

Facilitated by additional loans, the real value is the chance to experience the Albertina’s world-class collection of Western works on paper. All of their eight Michelangelo sheets are exhibited, but there’s a catch. For the five double-sided sheets, only one side is shown. Instead, the versos are represented by framed facsimiles to strengthen other sections, but the recto-verso relationship is frustratingly never mentioned. This misleads visitors into thinking they are independent sheets, which is not the case.

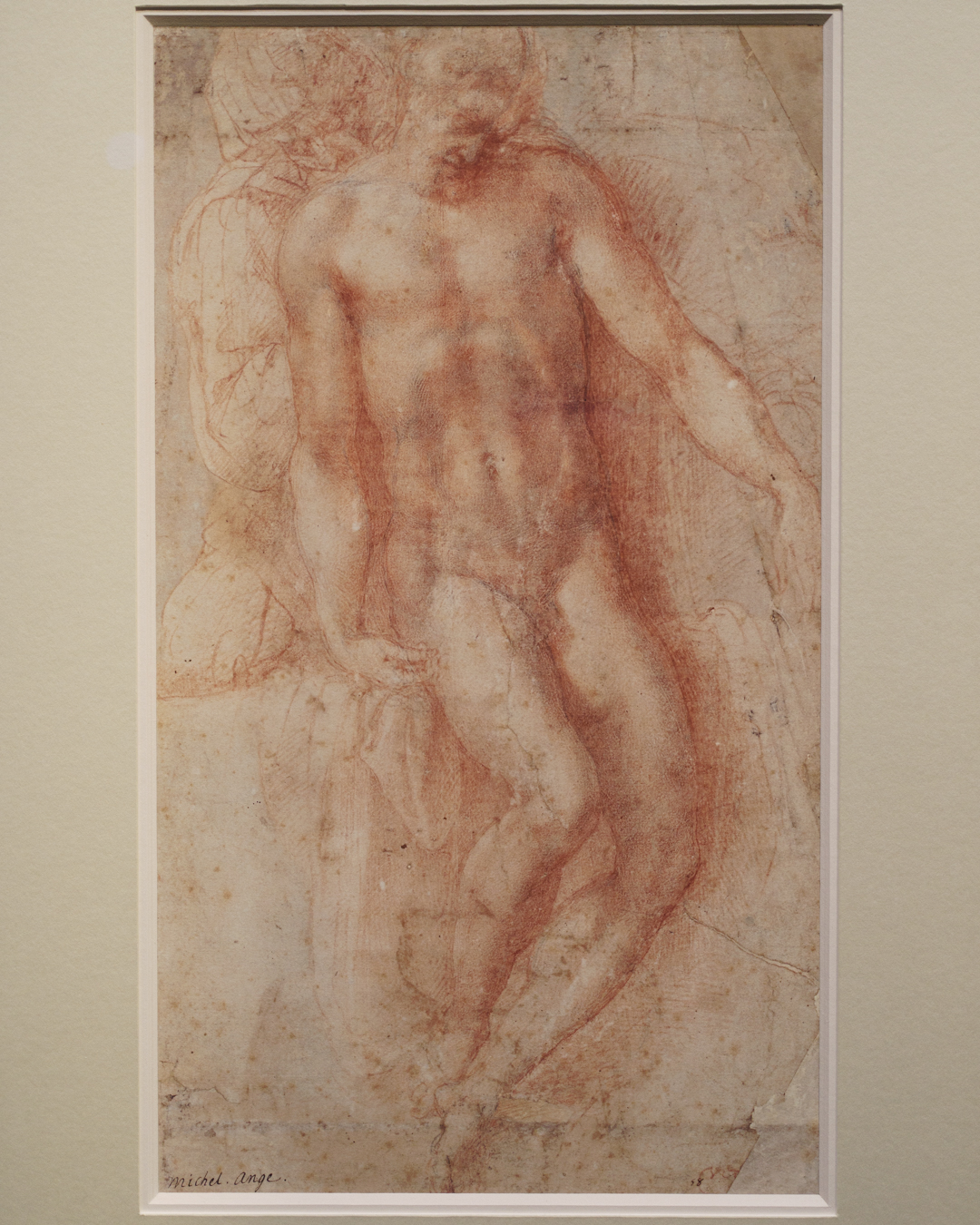

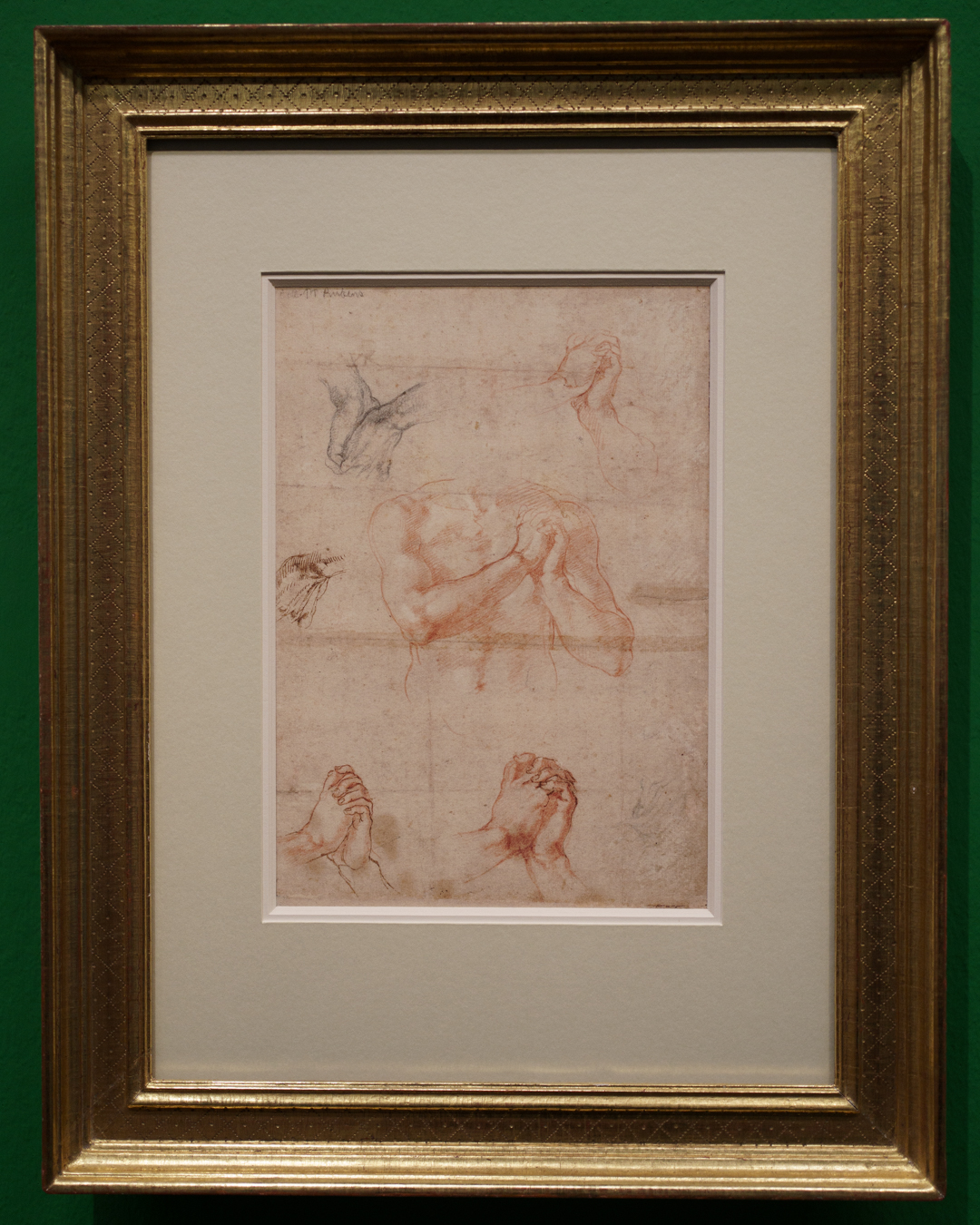

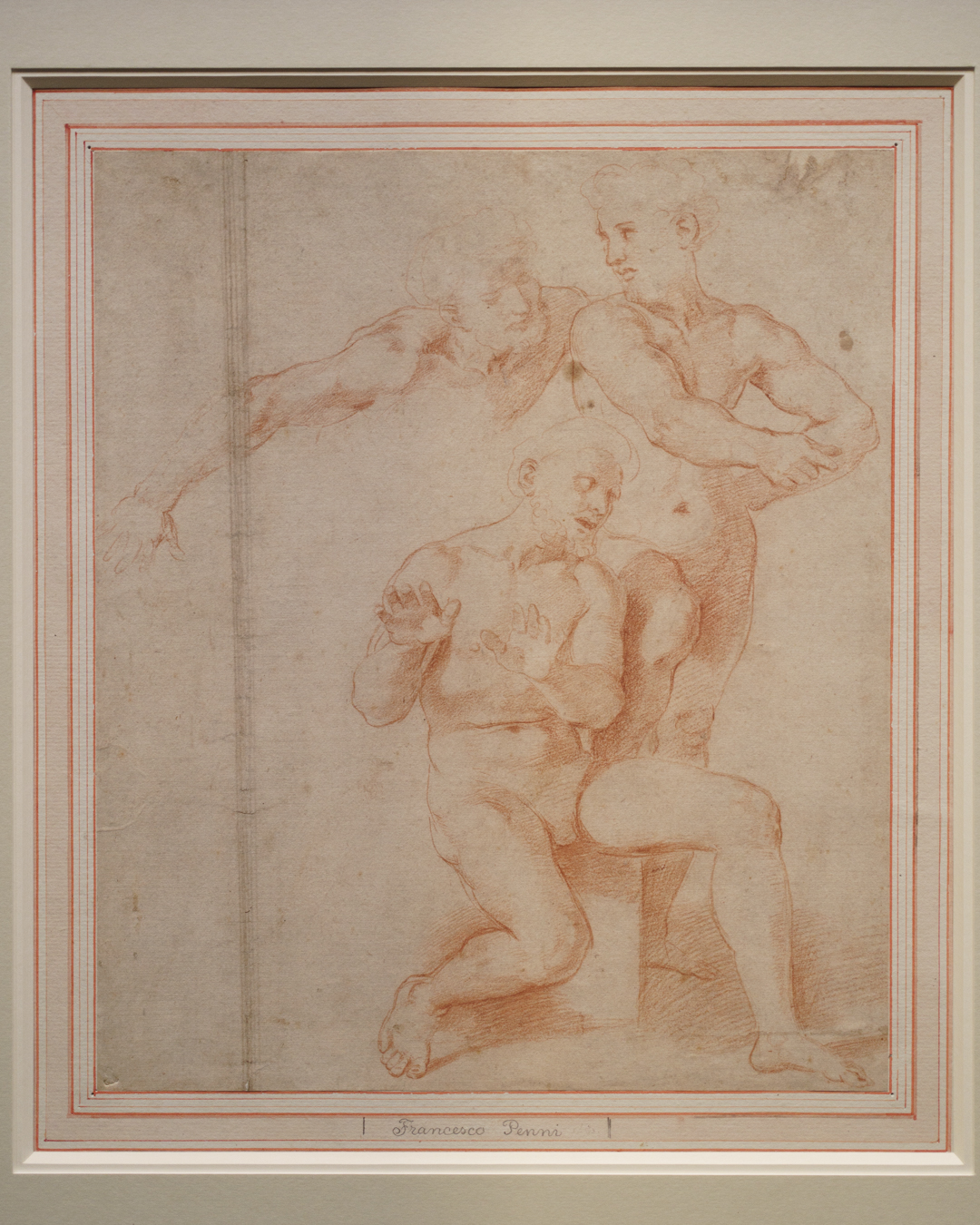

There is only one instance where both sides are divided between rooms: the red-chalk seated Sistine Chapel ignudo with studies for Sebastiano del Piombo‘s Pietà (Museo Civico, Viterbo) on the back. The recto is brilliantly paired with the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s famous study for the Libyan Sibyl, a most enviable loan. One also has the opportunity to see last year’s rediscovered early Michelangelo drawing (after Masaccio), but it is annoyingly grouped away from the Albertina’s related sheet, eluding opportunities for comparison. In total, 14 Michelangelo sheets are present, including loans from the Louvre.

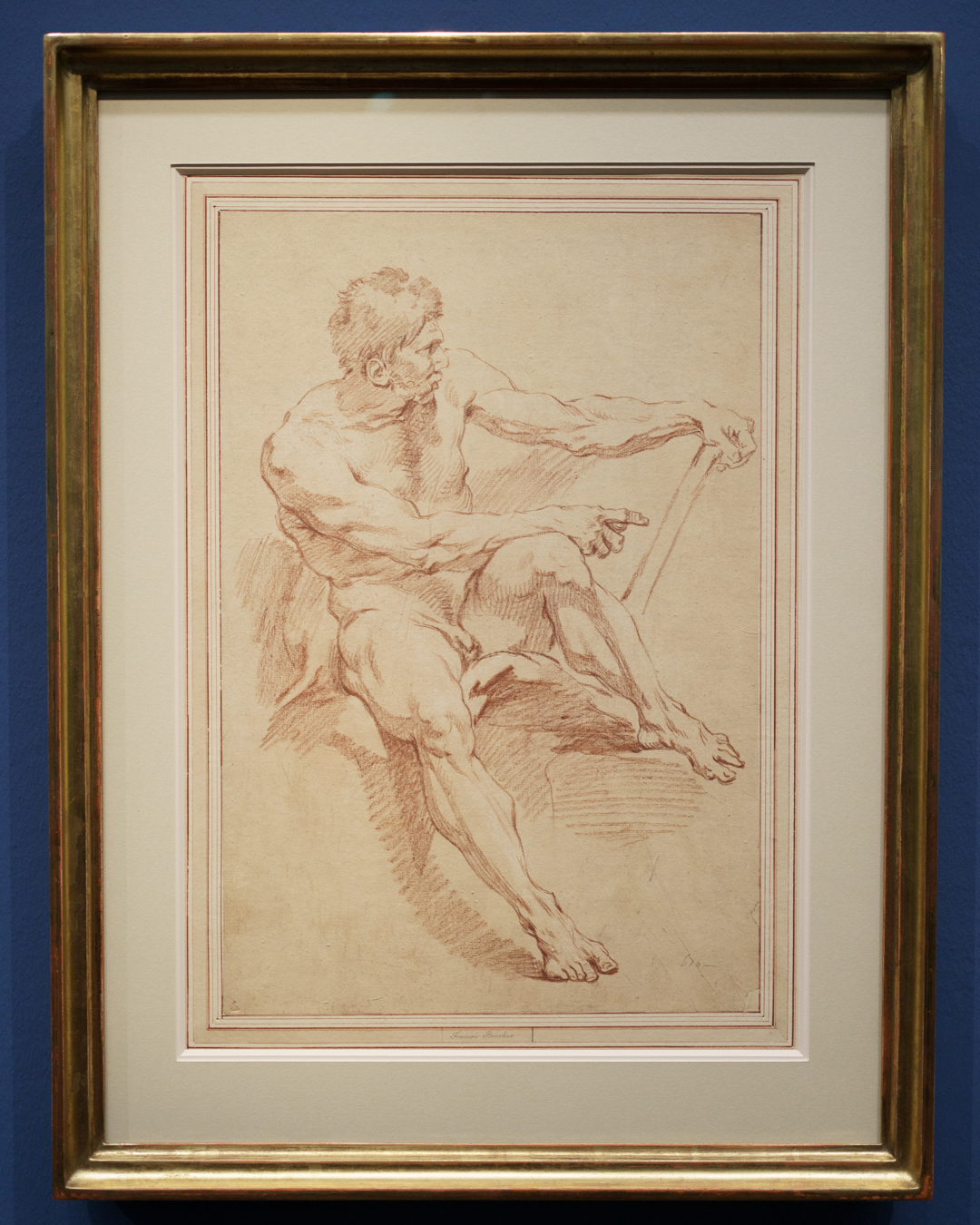

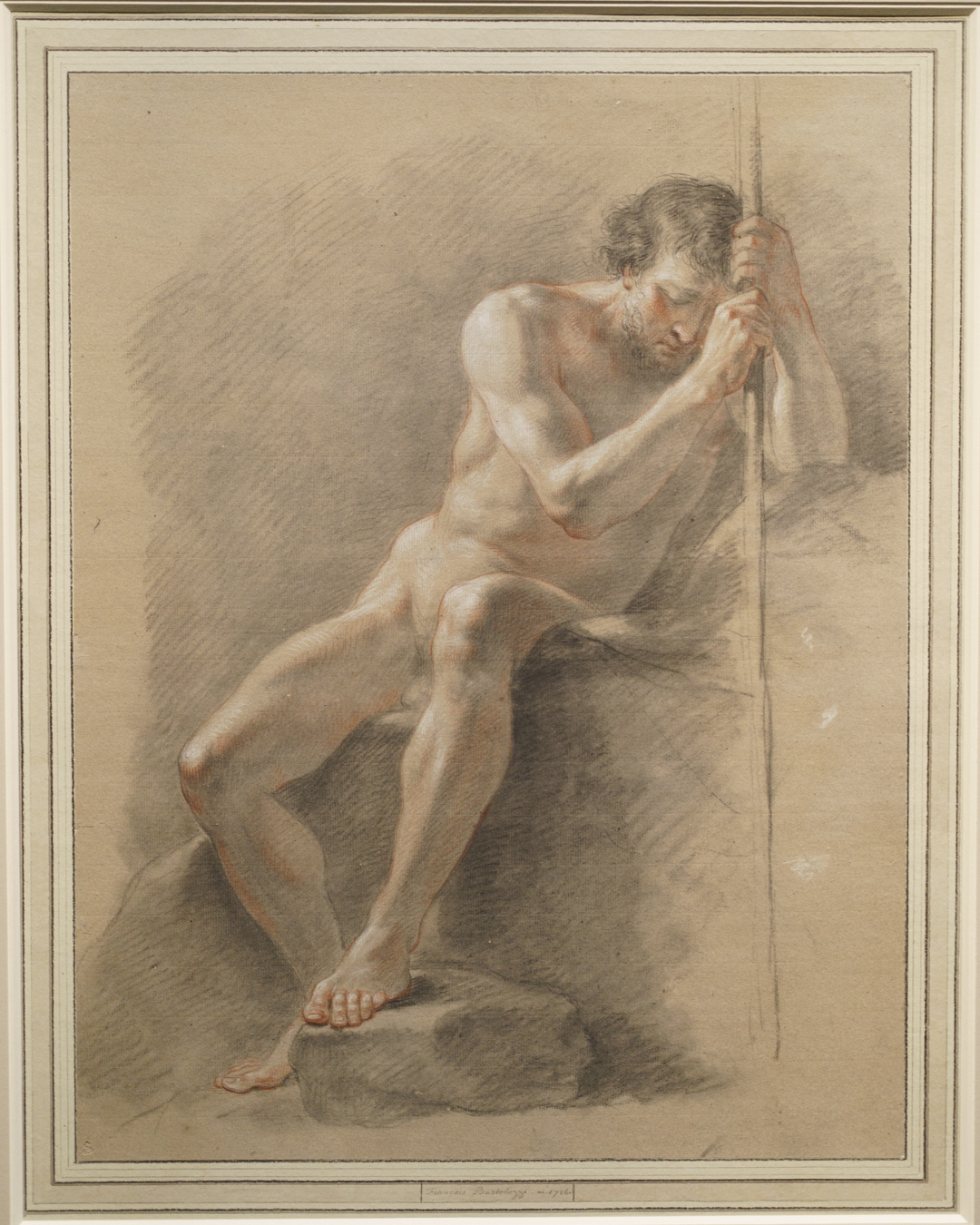

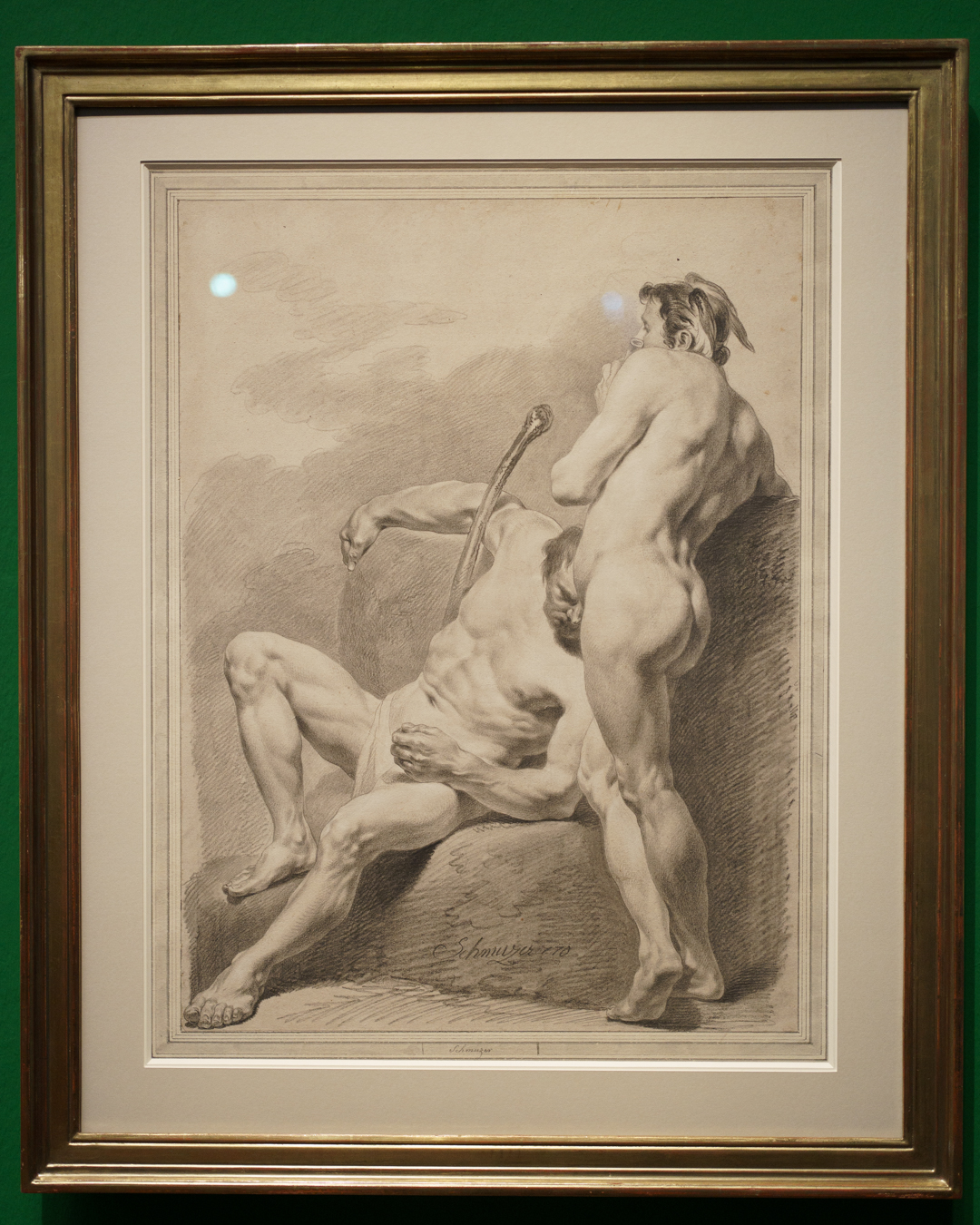

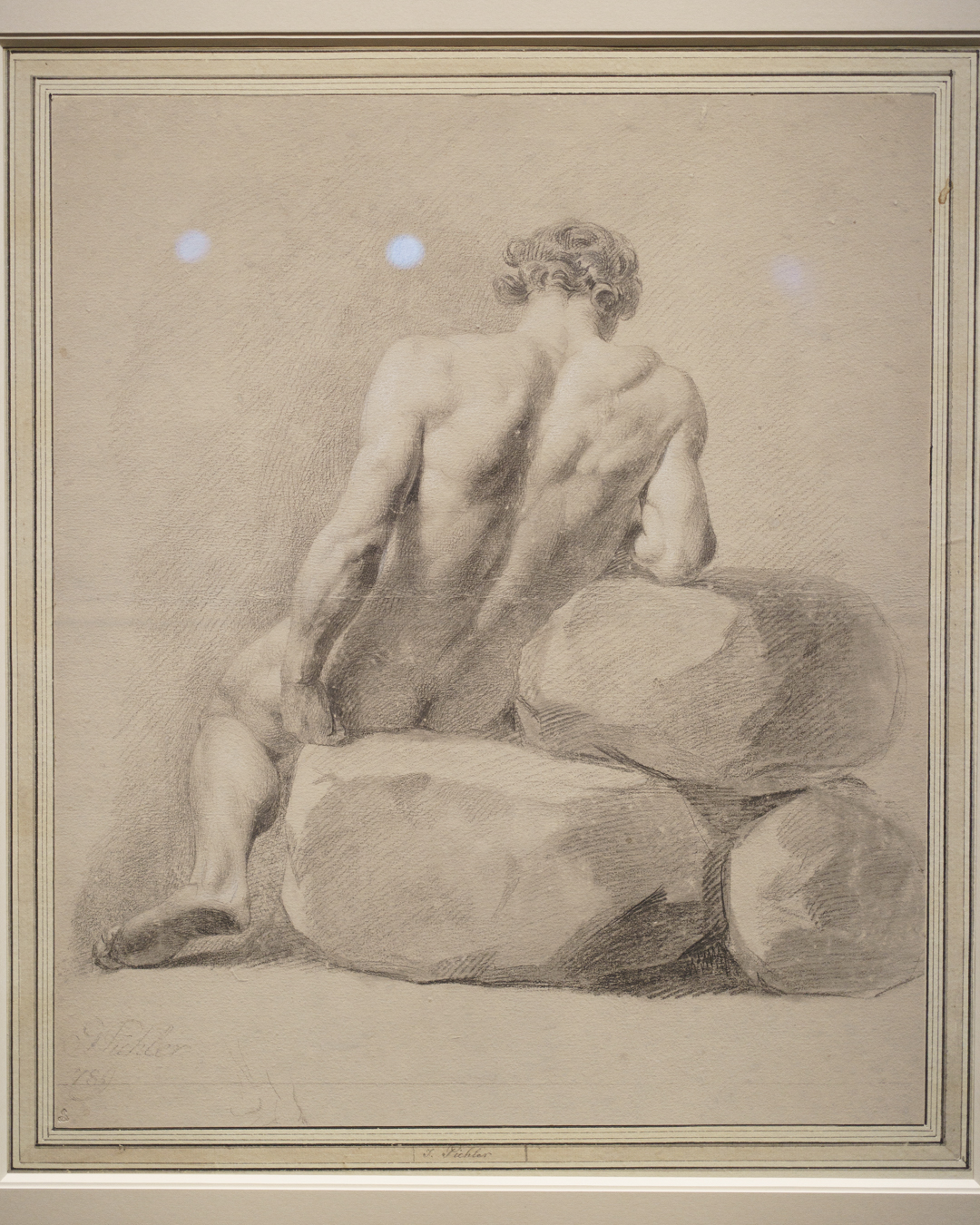

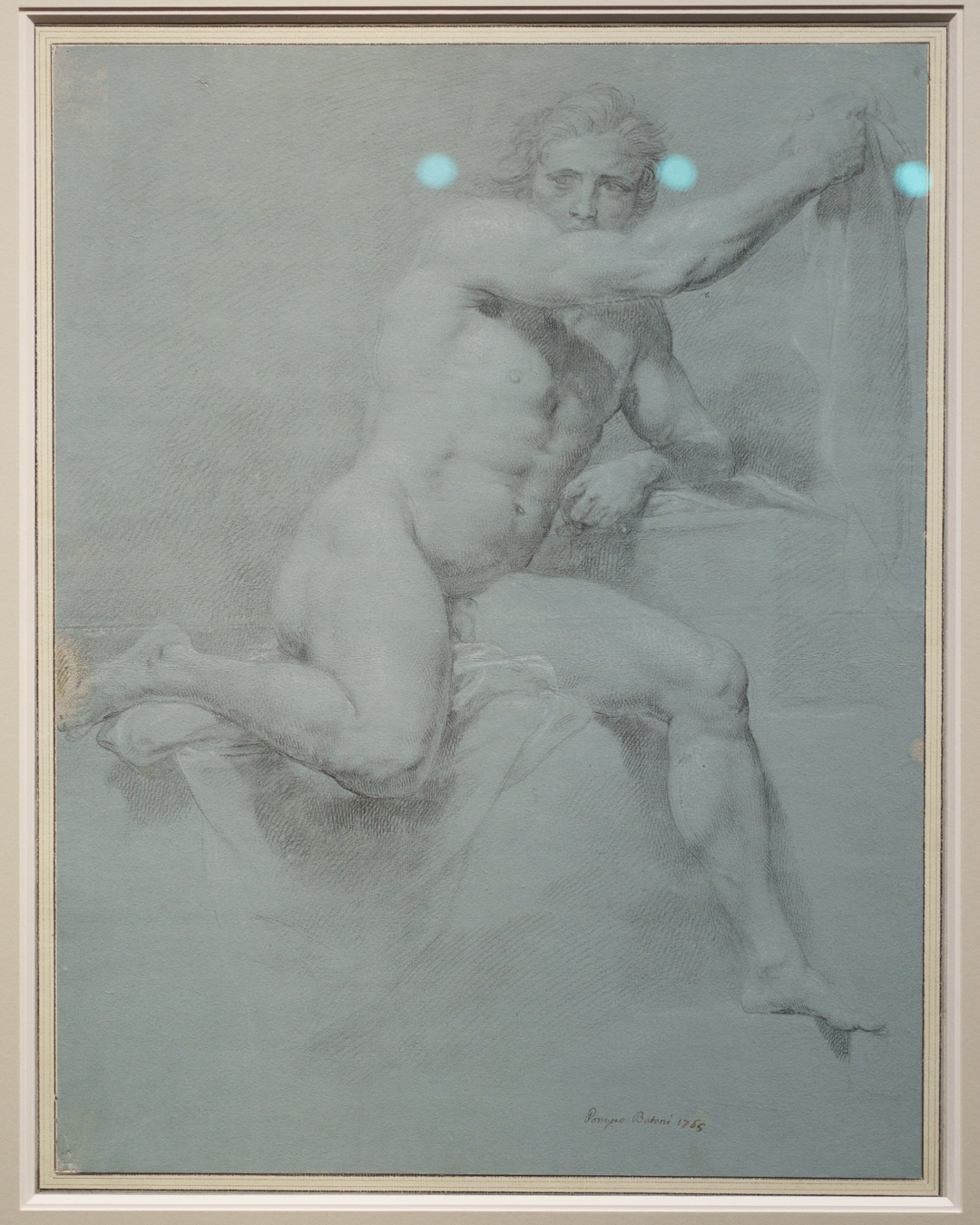

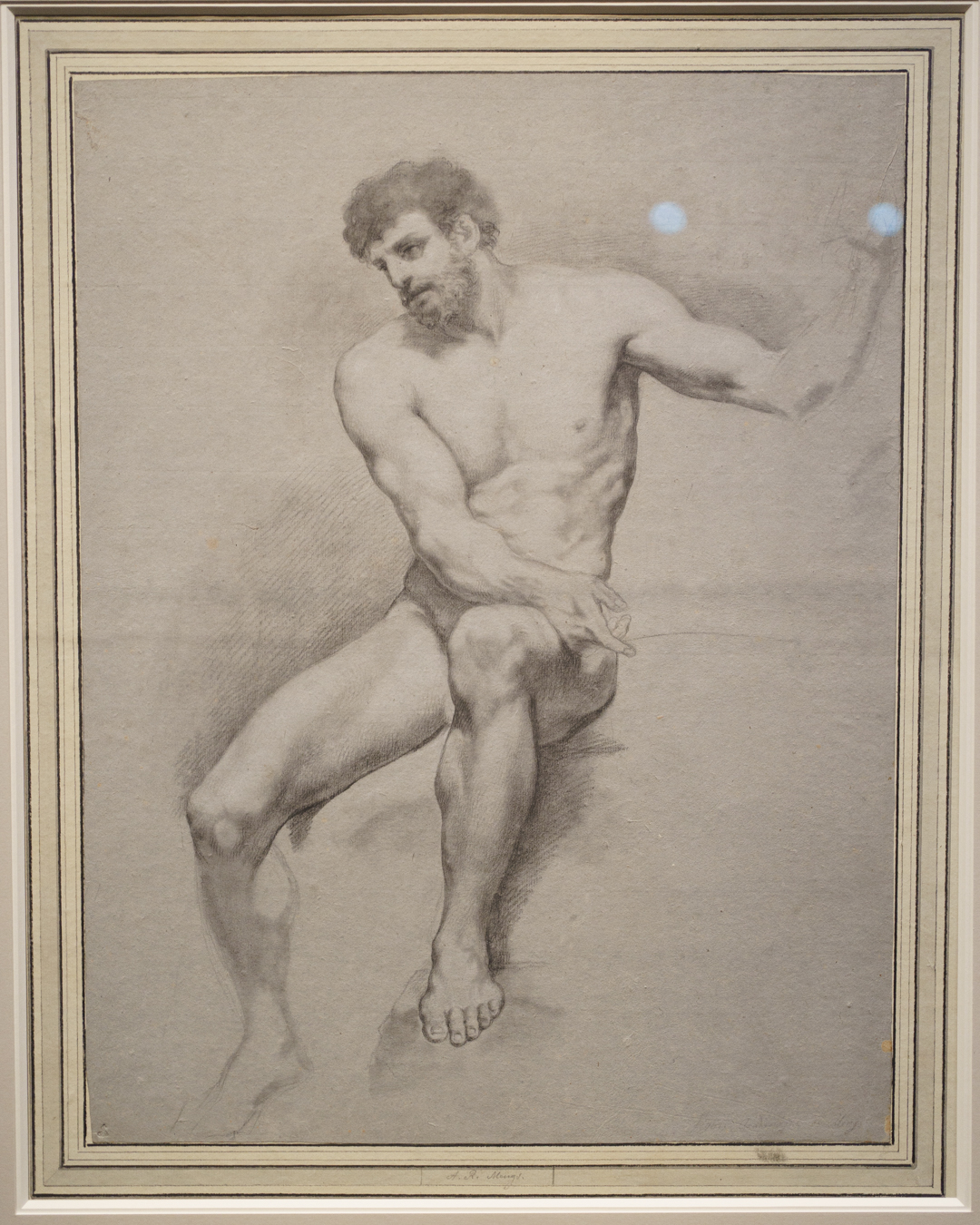

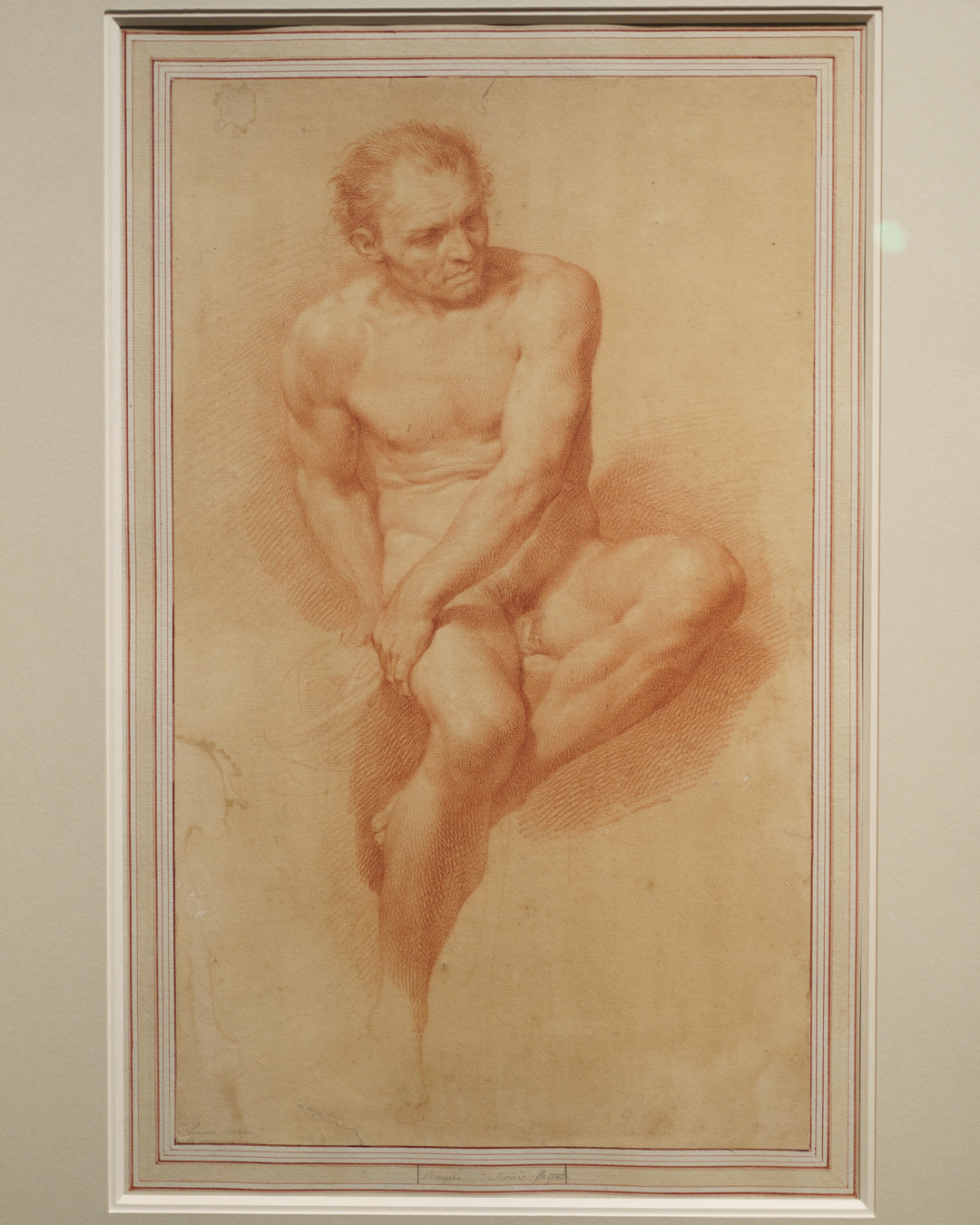

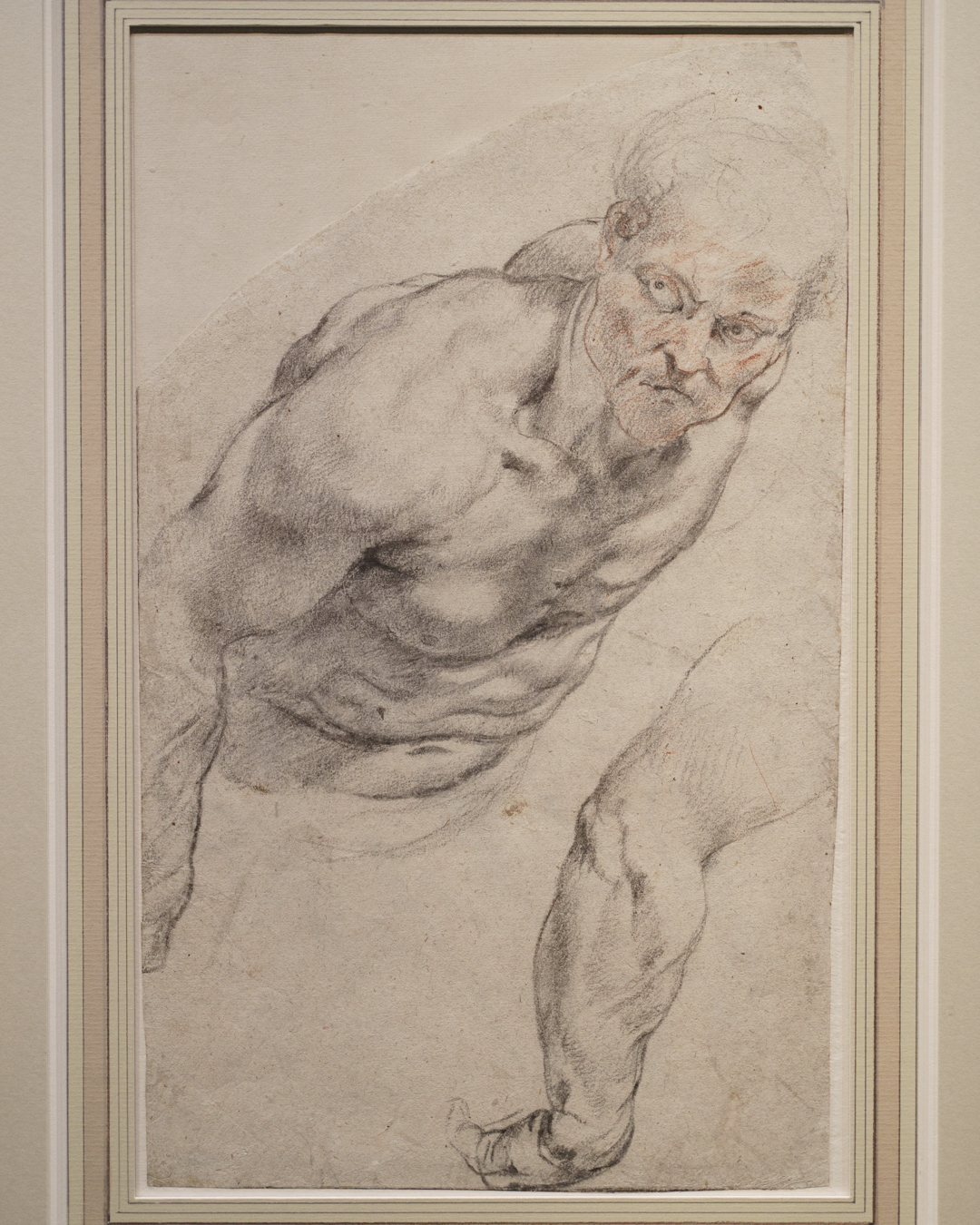

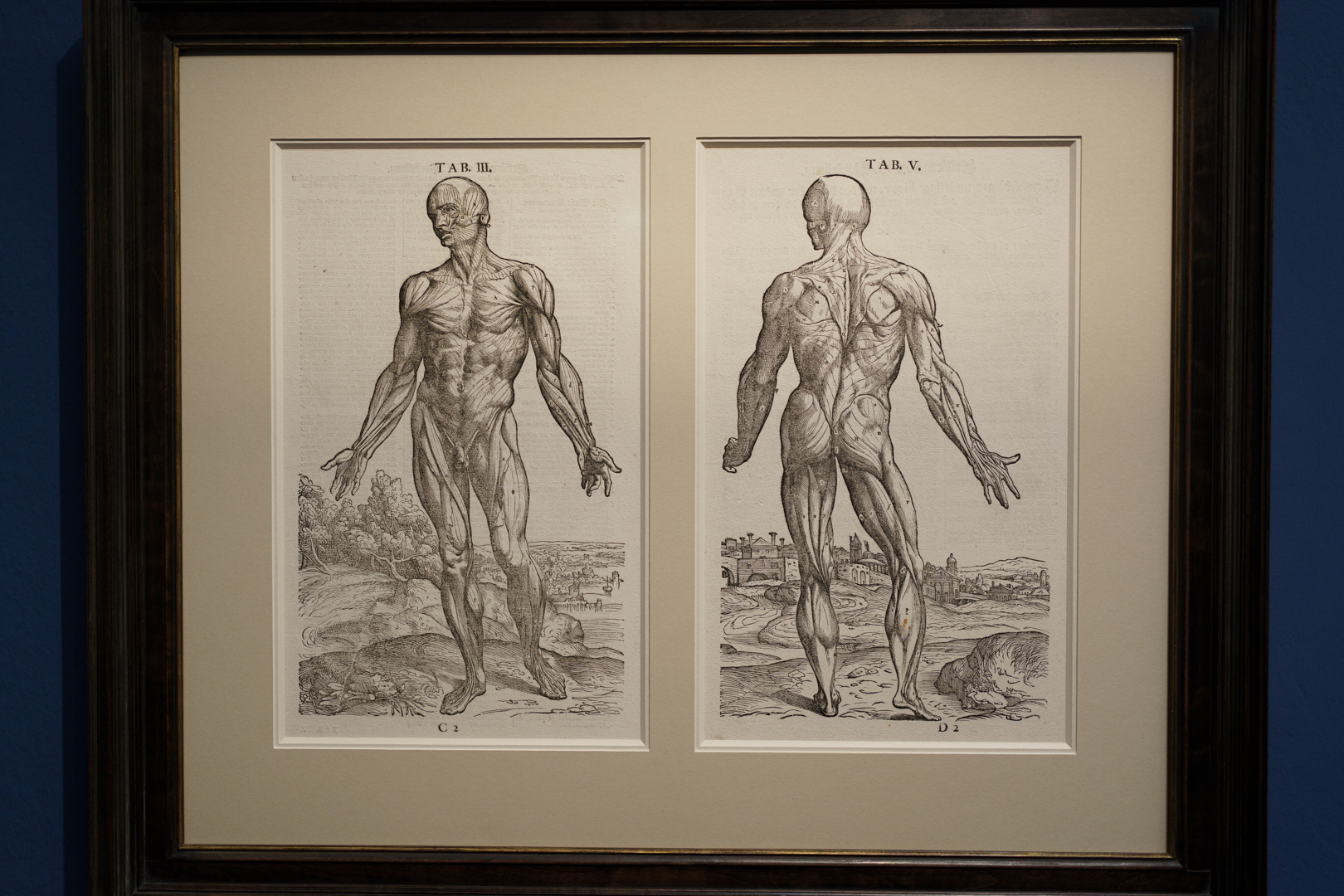

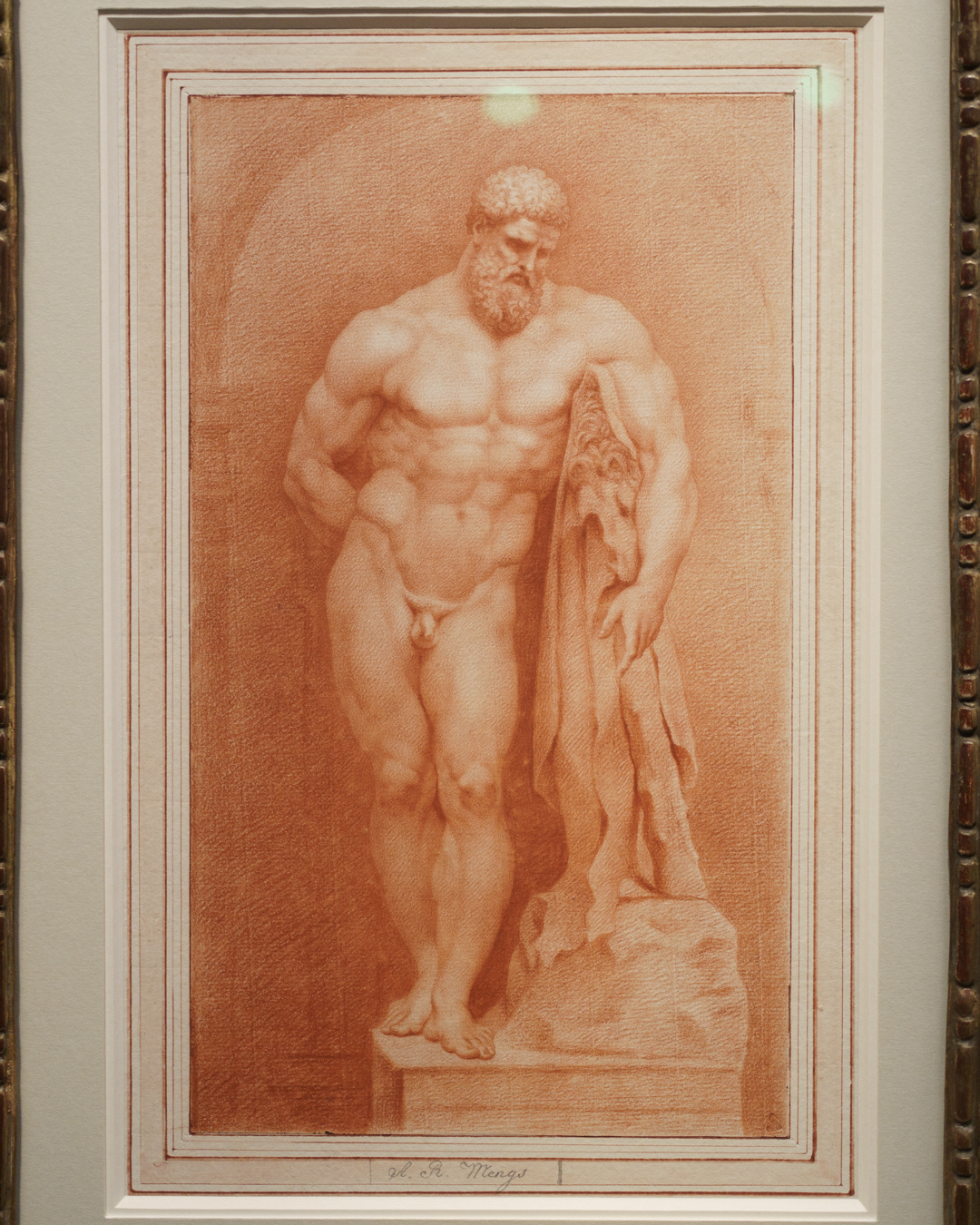

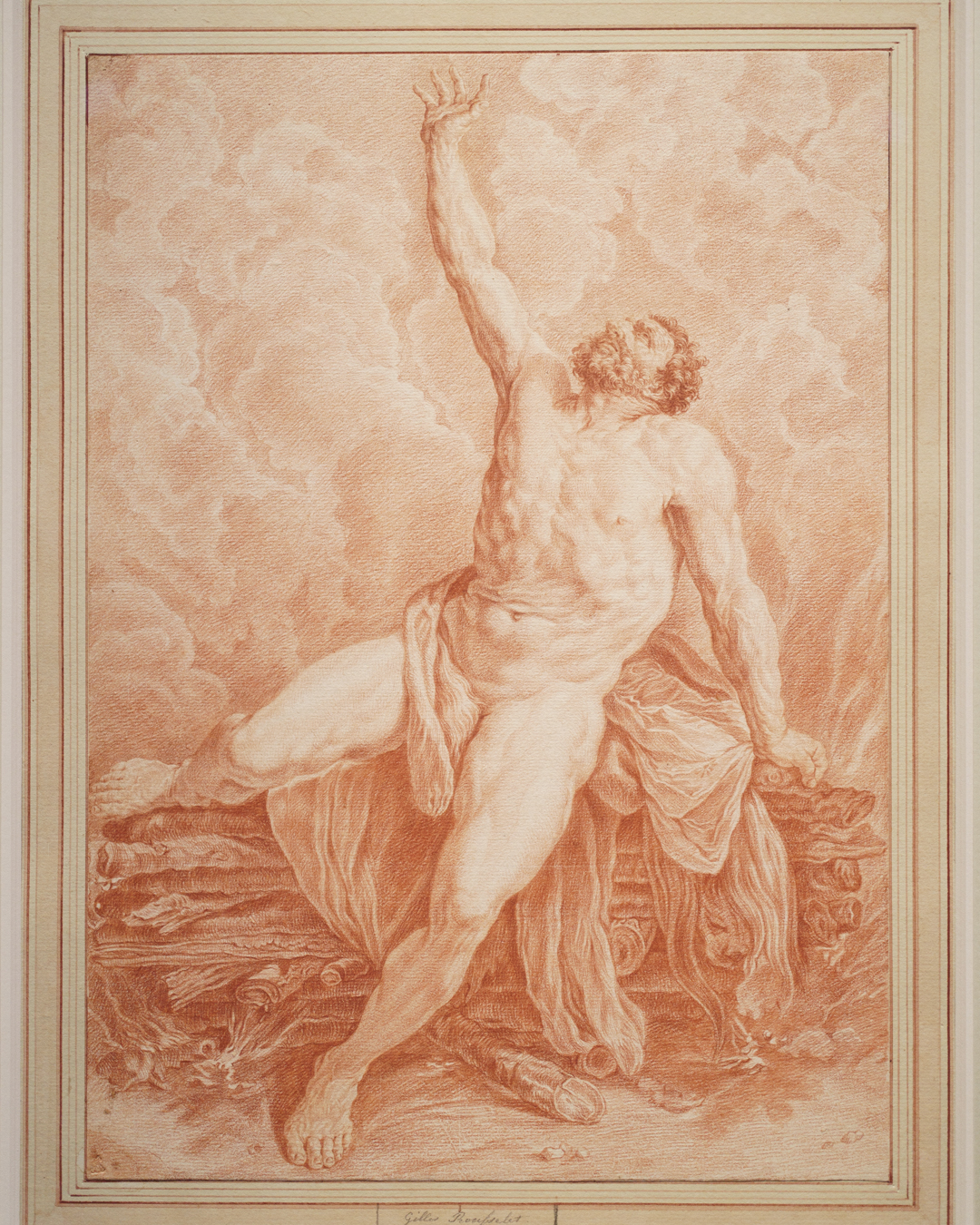

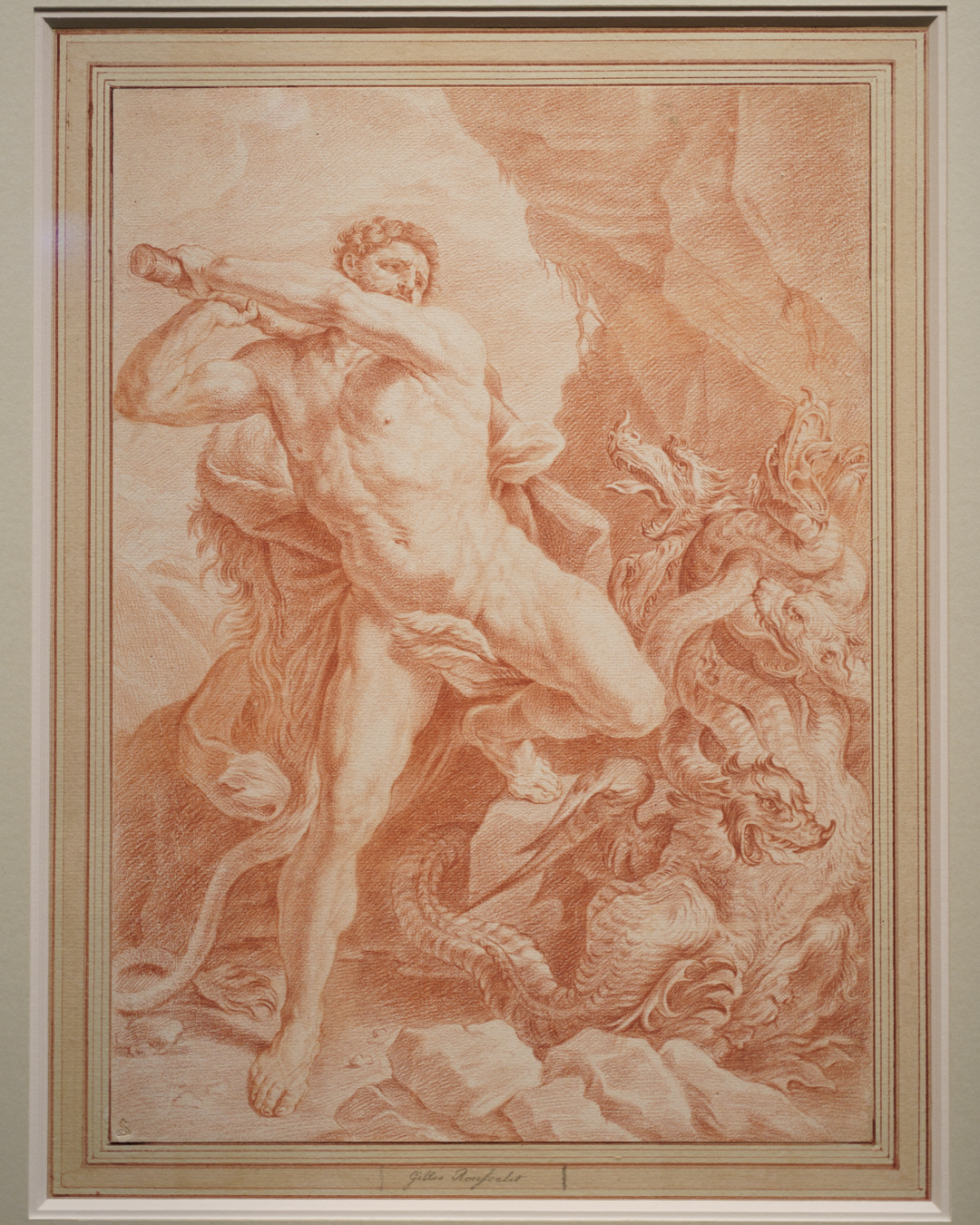

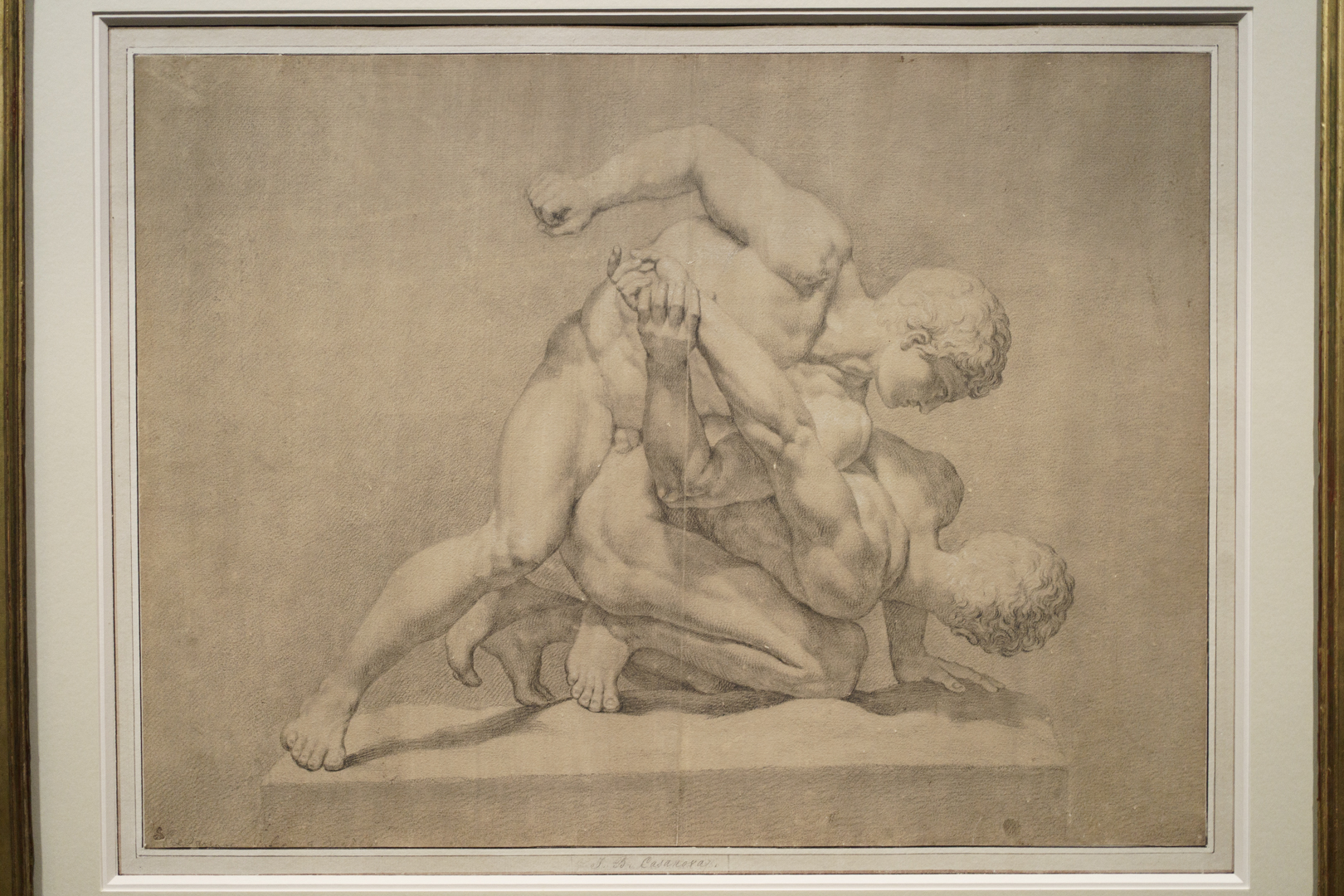

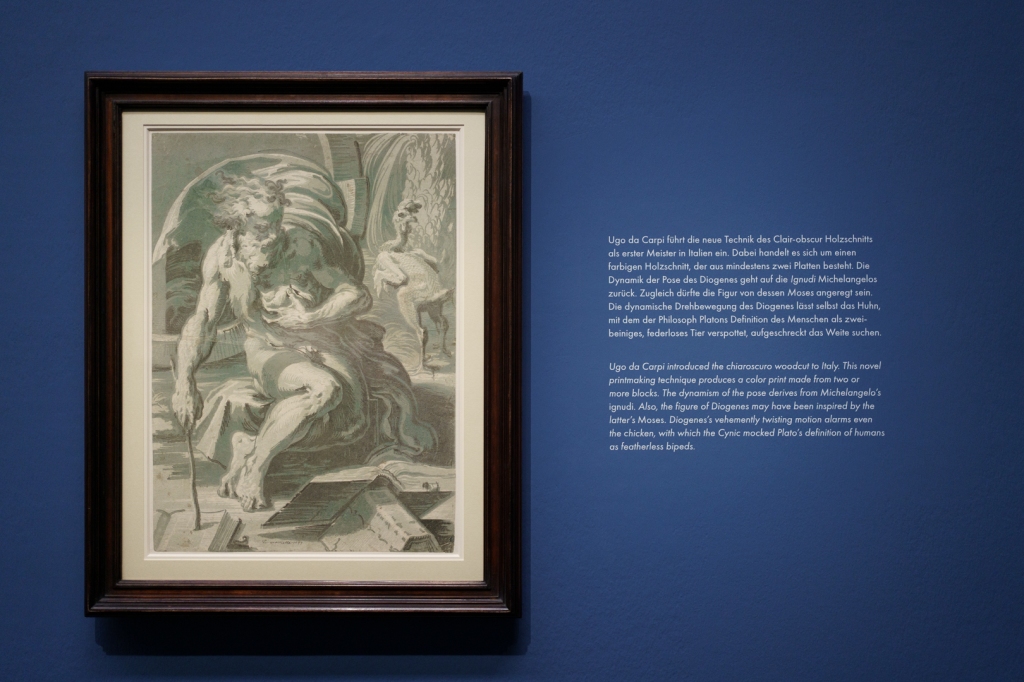

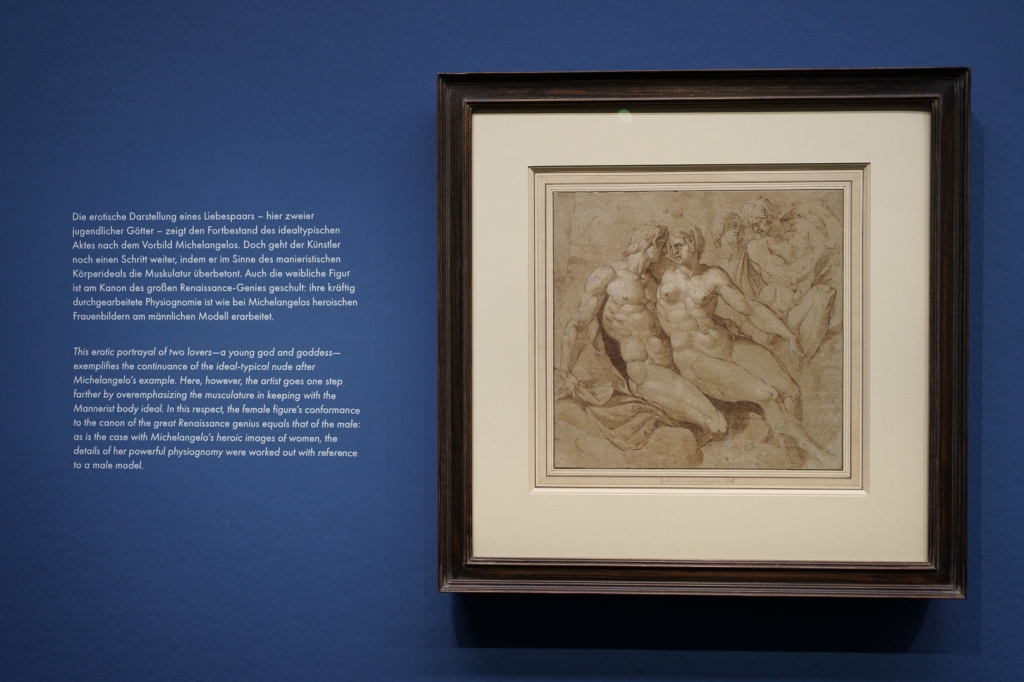

More than half of the exhibition is dedicated to male nudes, highlighting their reception as visual exemplars worthy of detailed anatomical study, but also availability in the form of antique sculptures and life models, a dual focus which has its own room (Room 5). The persistent agenda to frame everything as either adhering or rejecting Michelangelesque ideals was irritating and discursively minor within a sea of actually rather interesting thematic presentations.

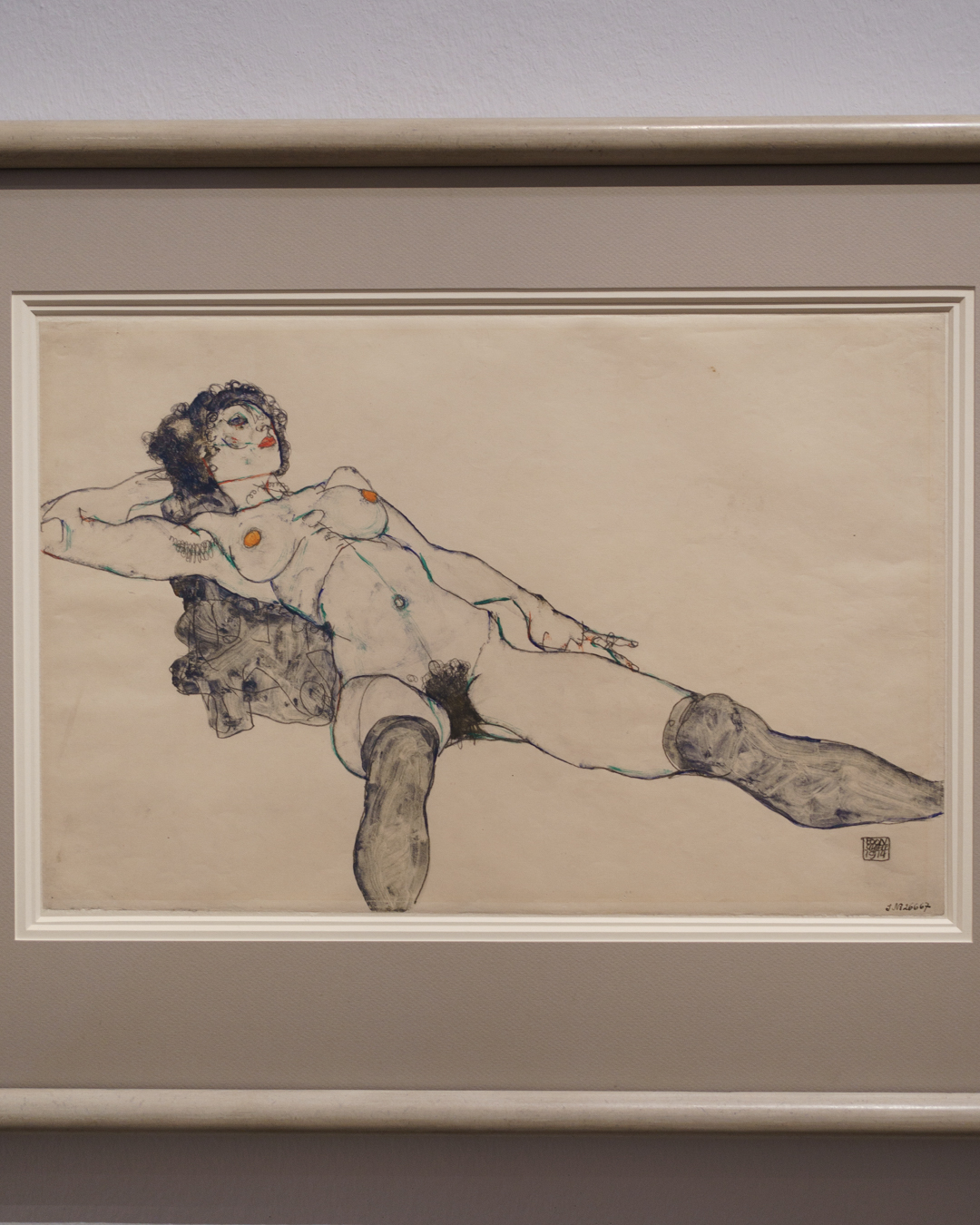

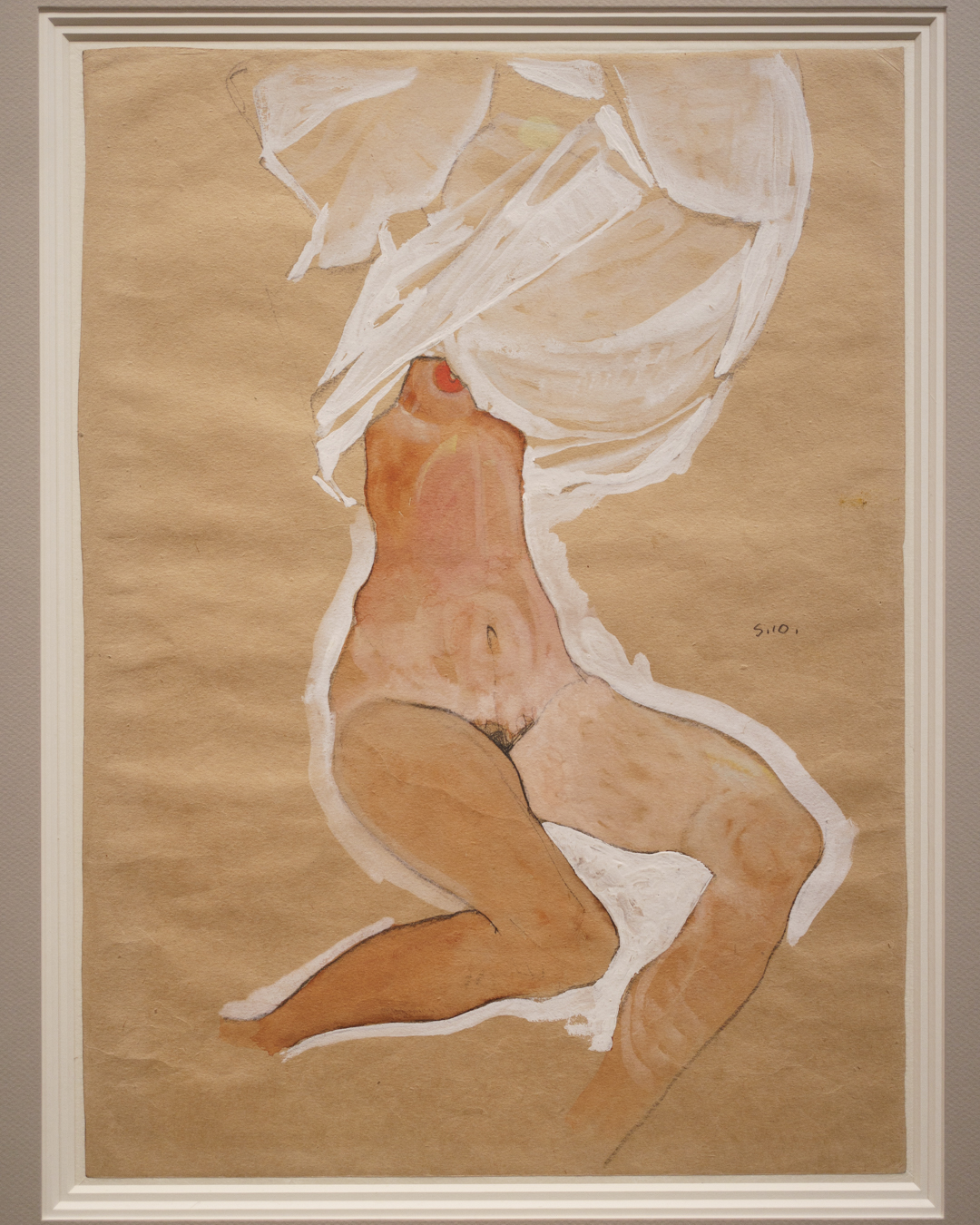

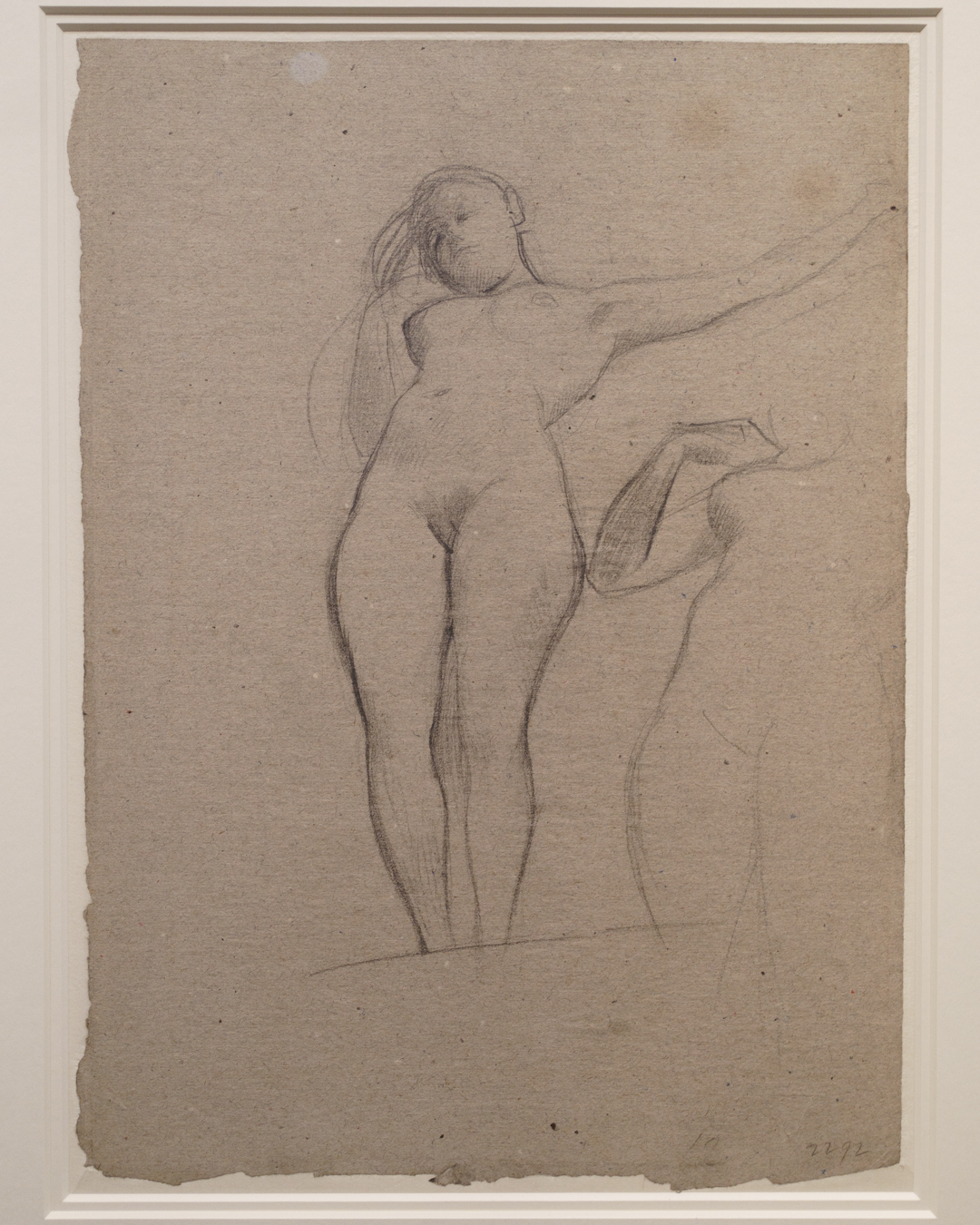

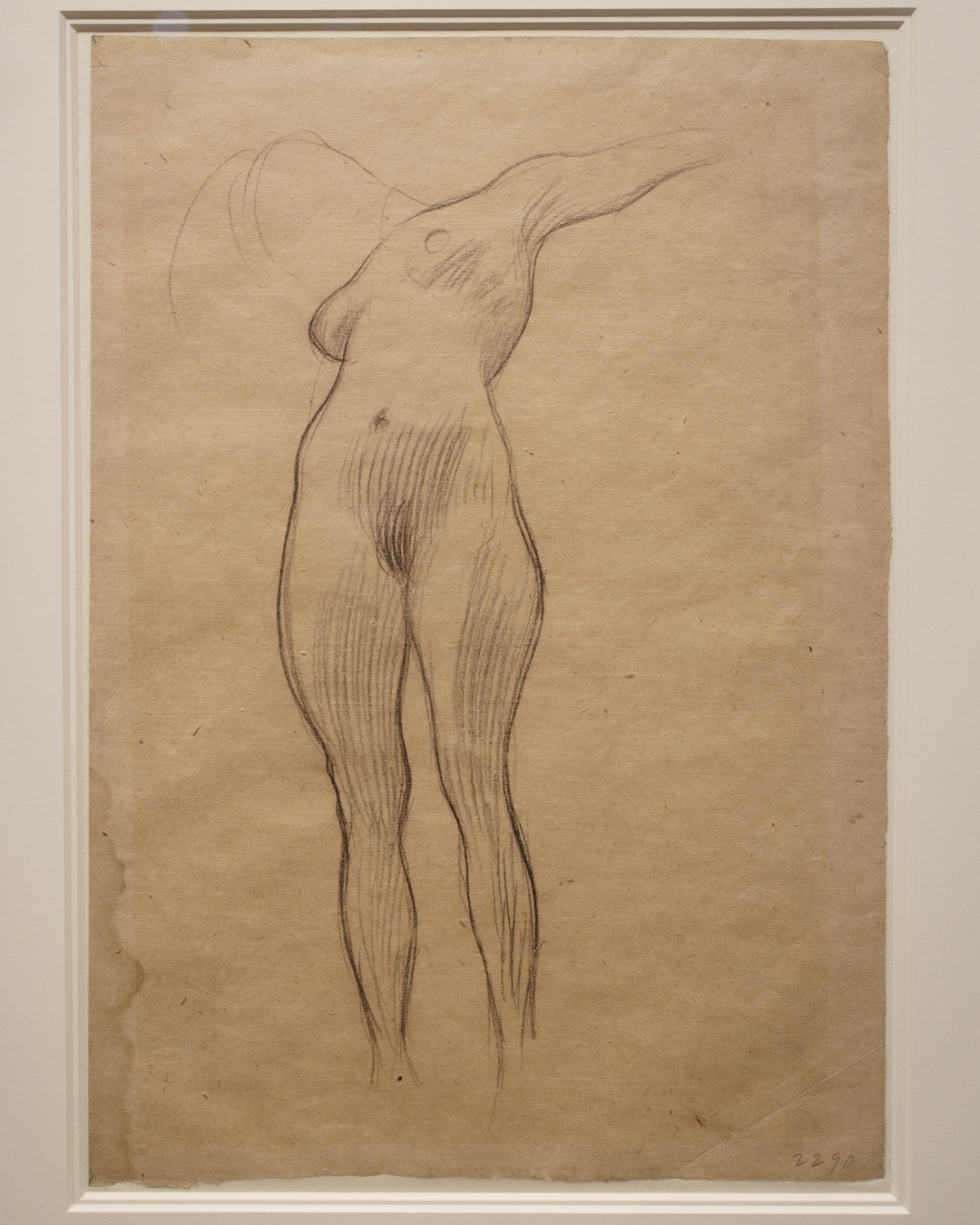

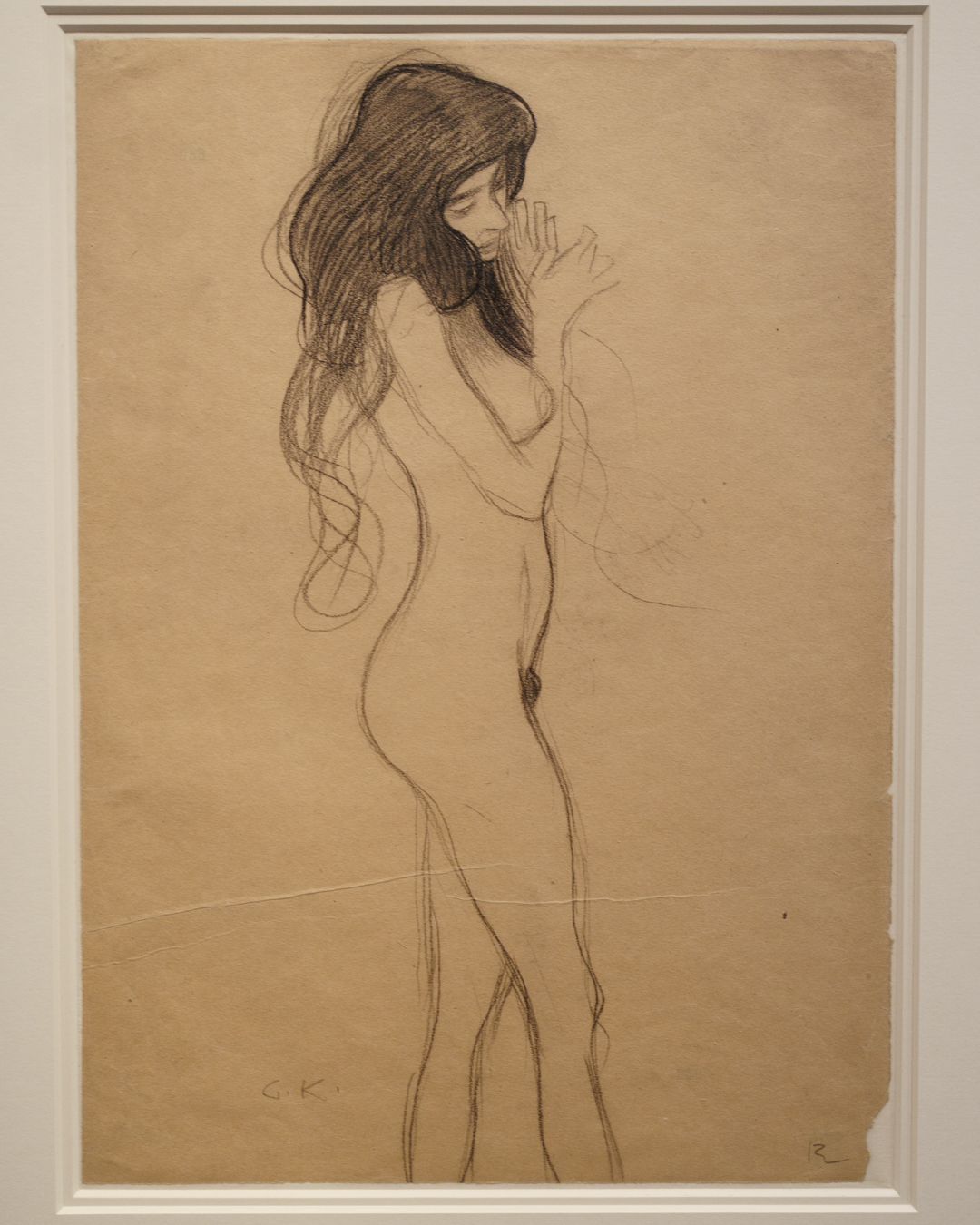

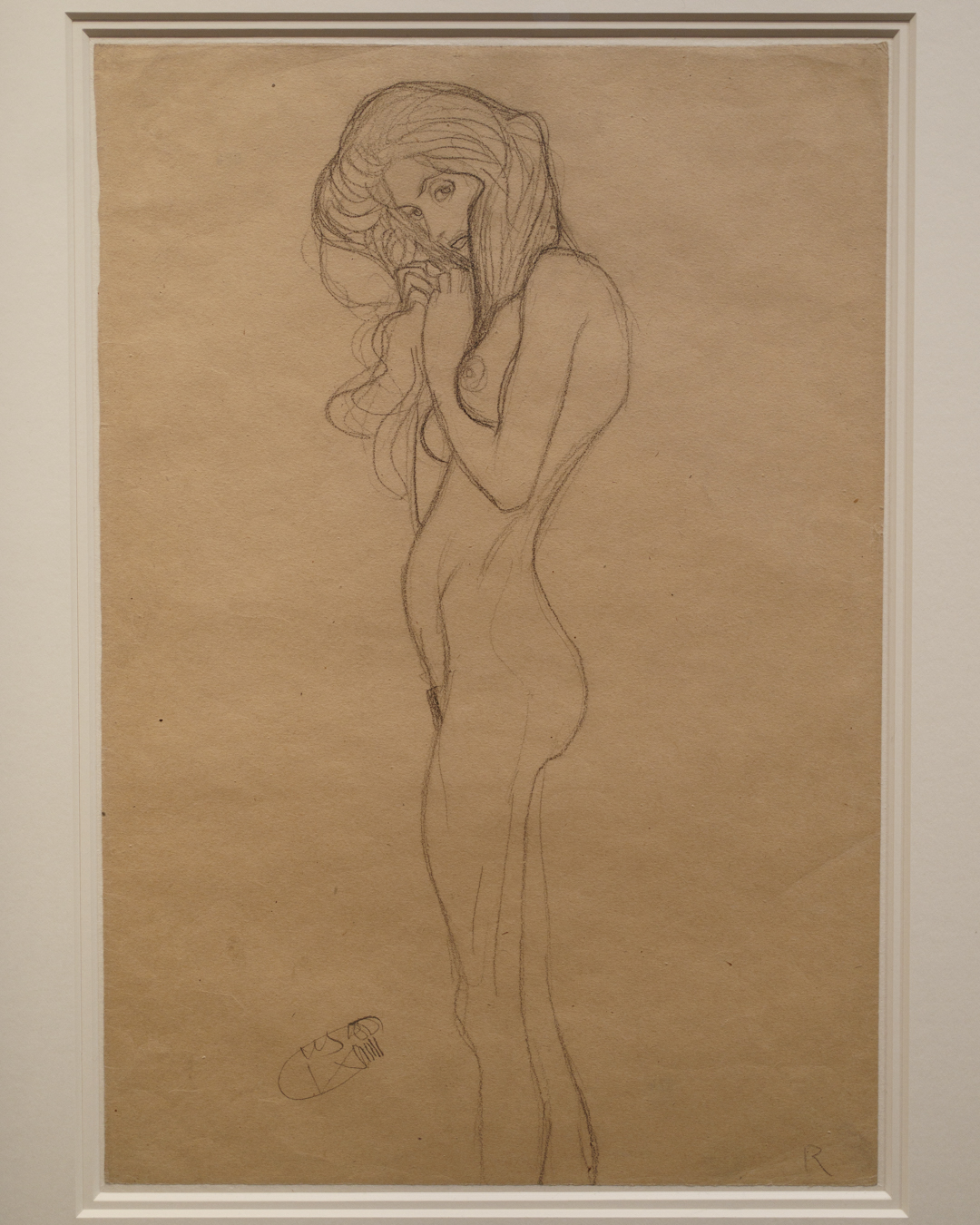

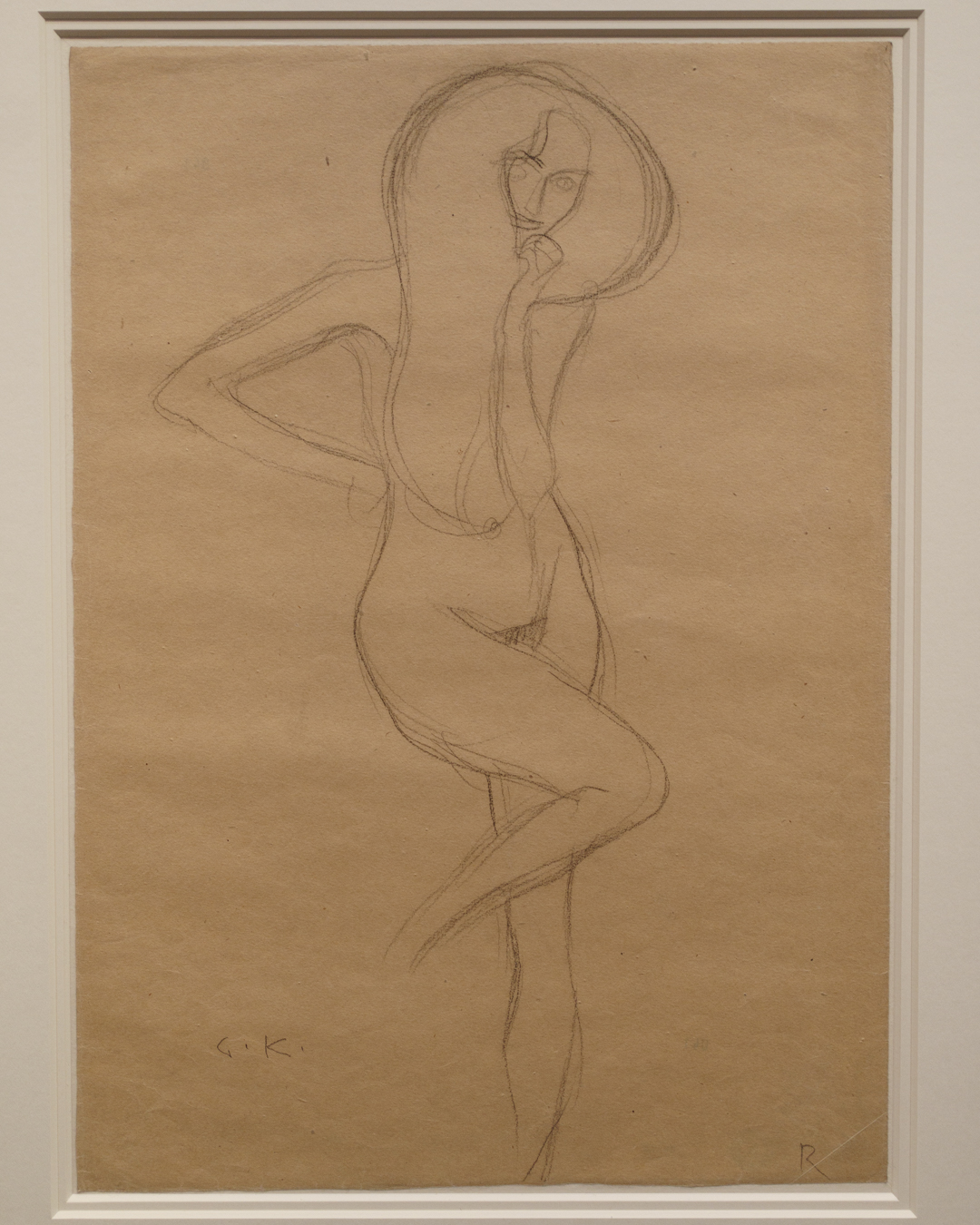

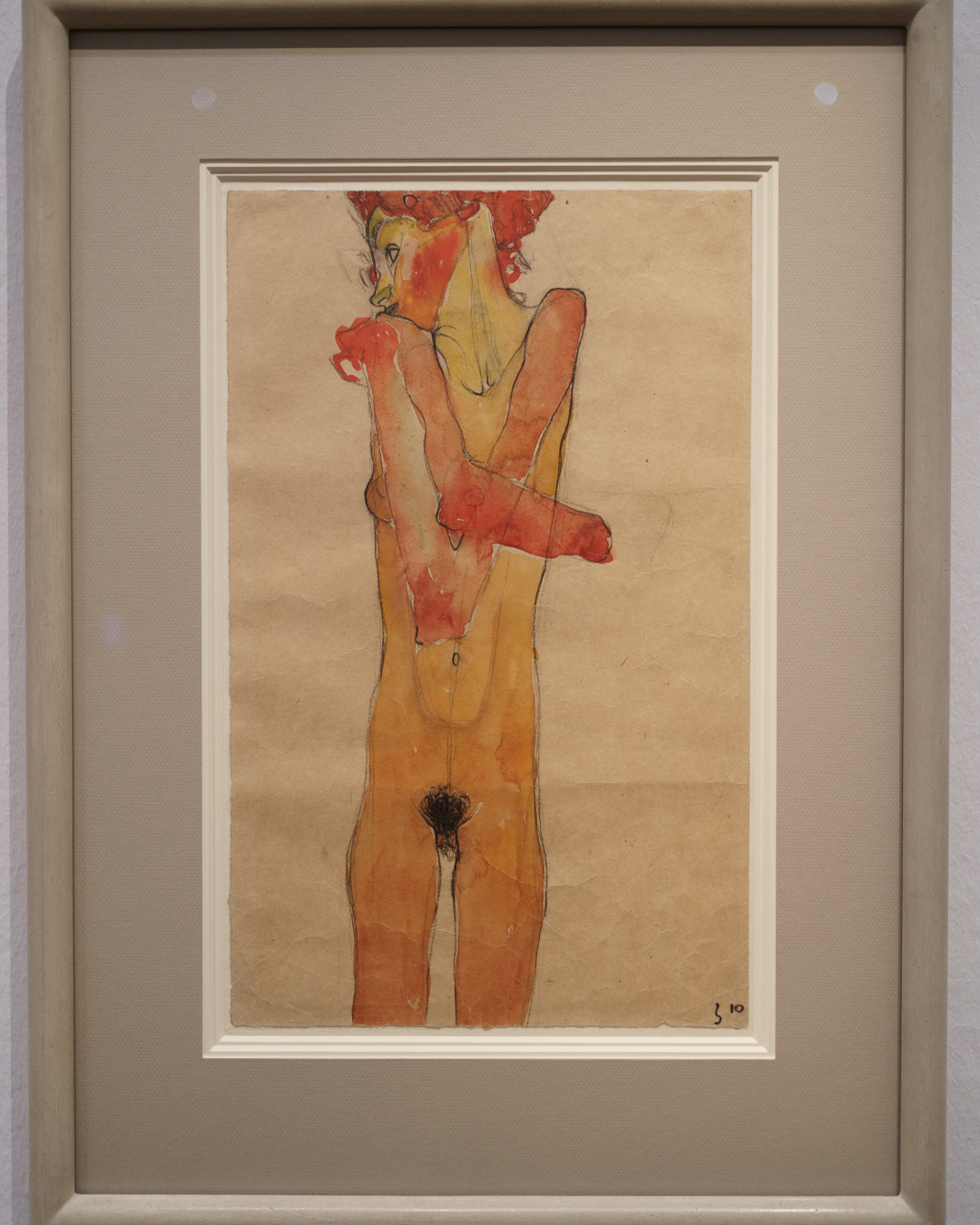

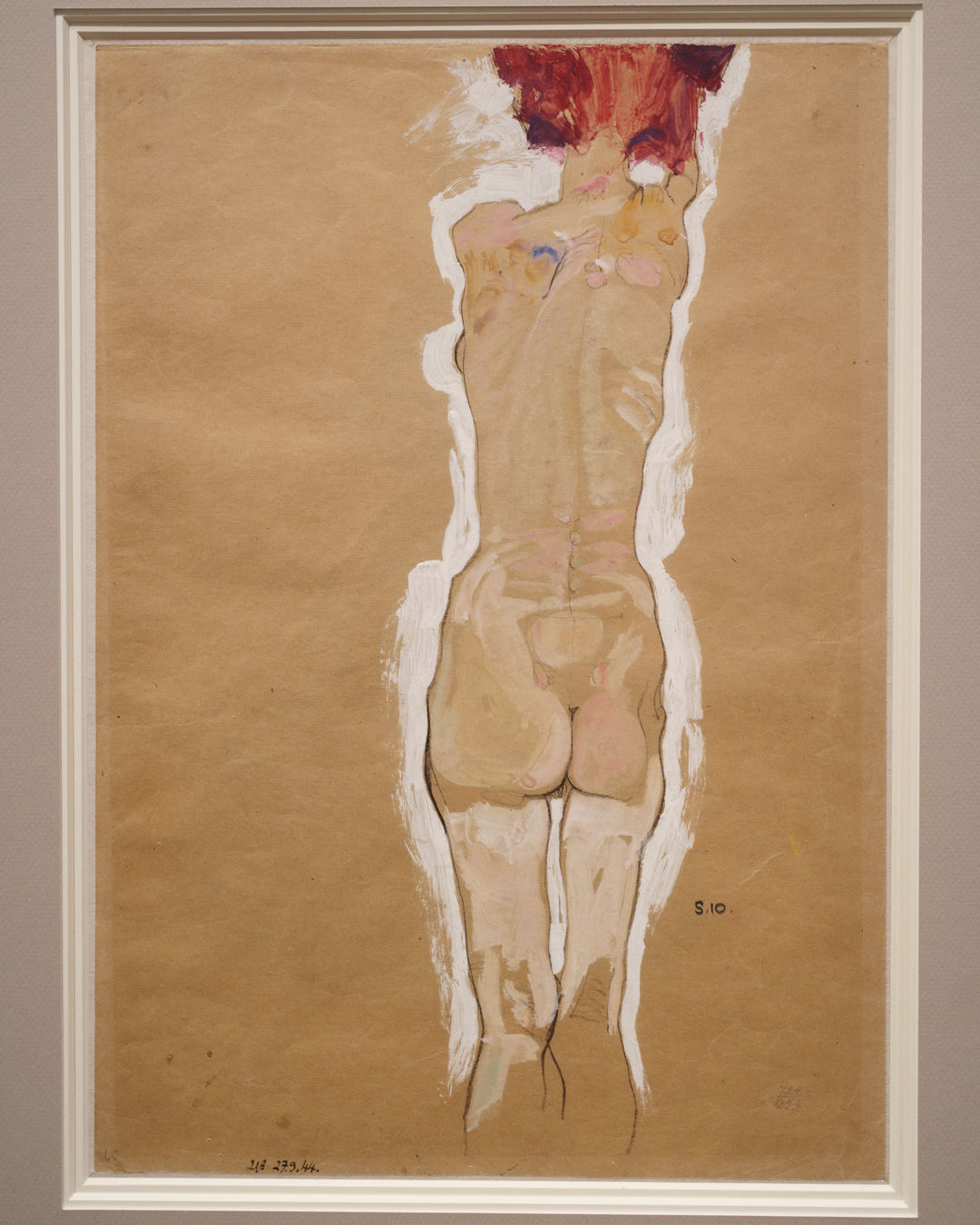

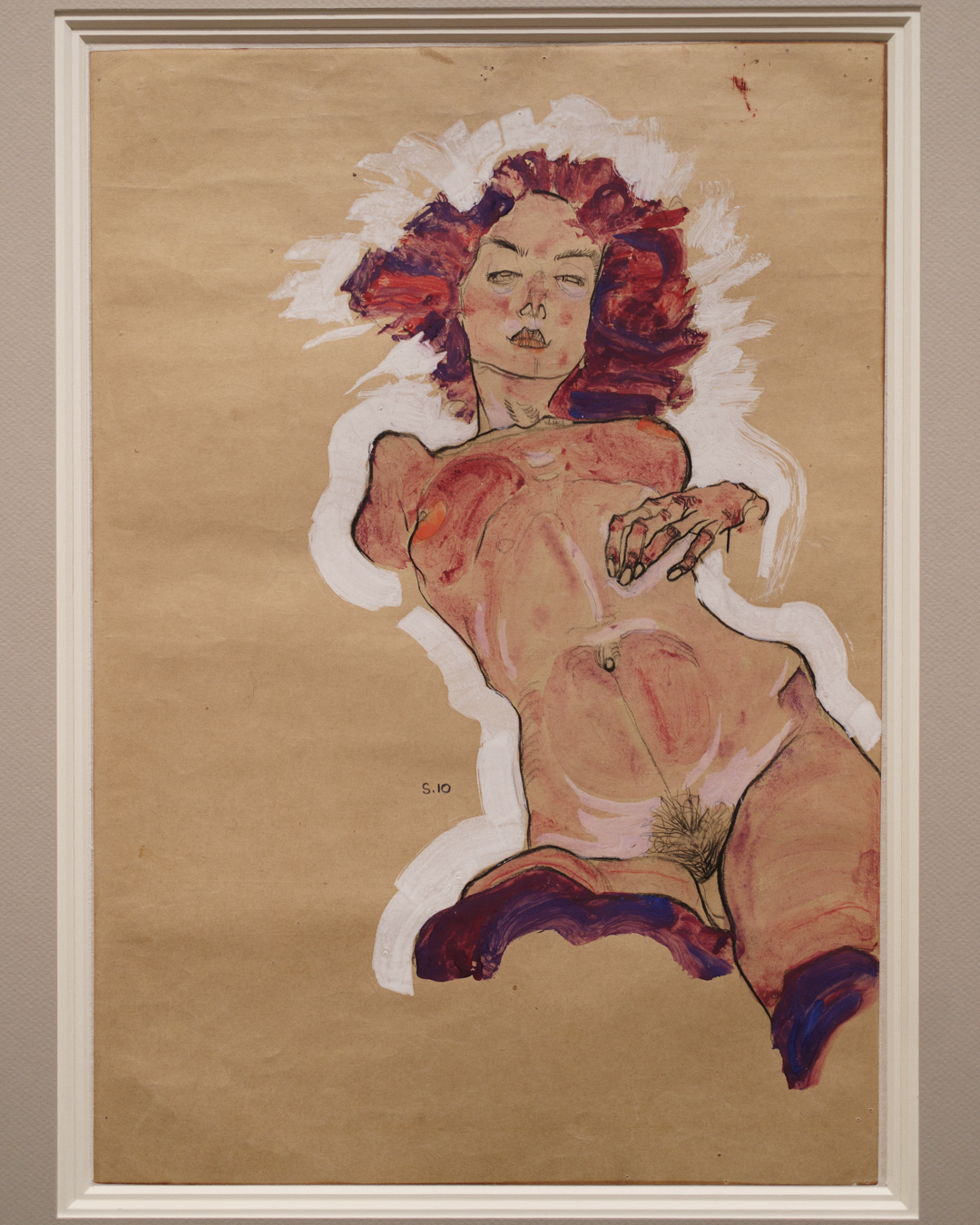

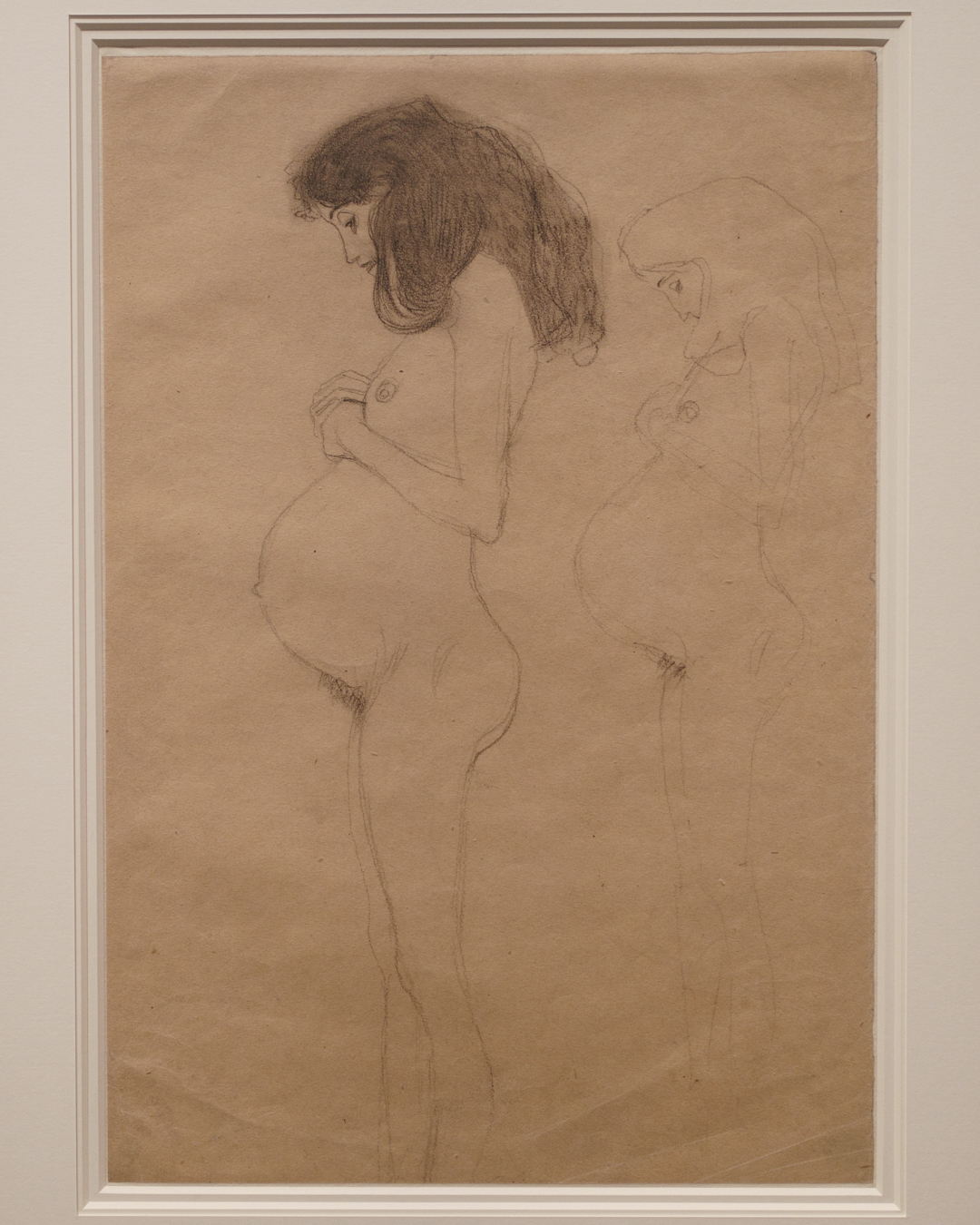

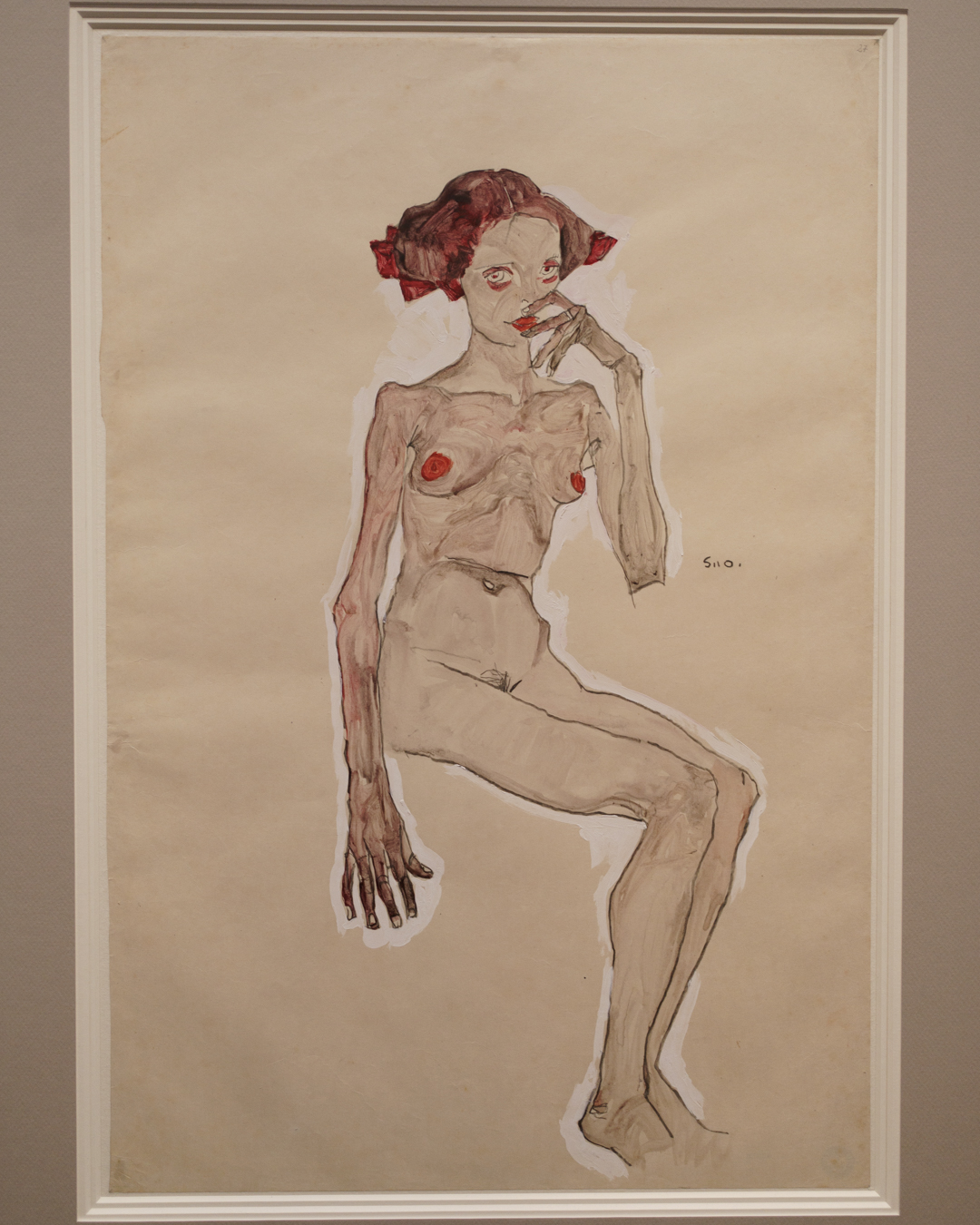

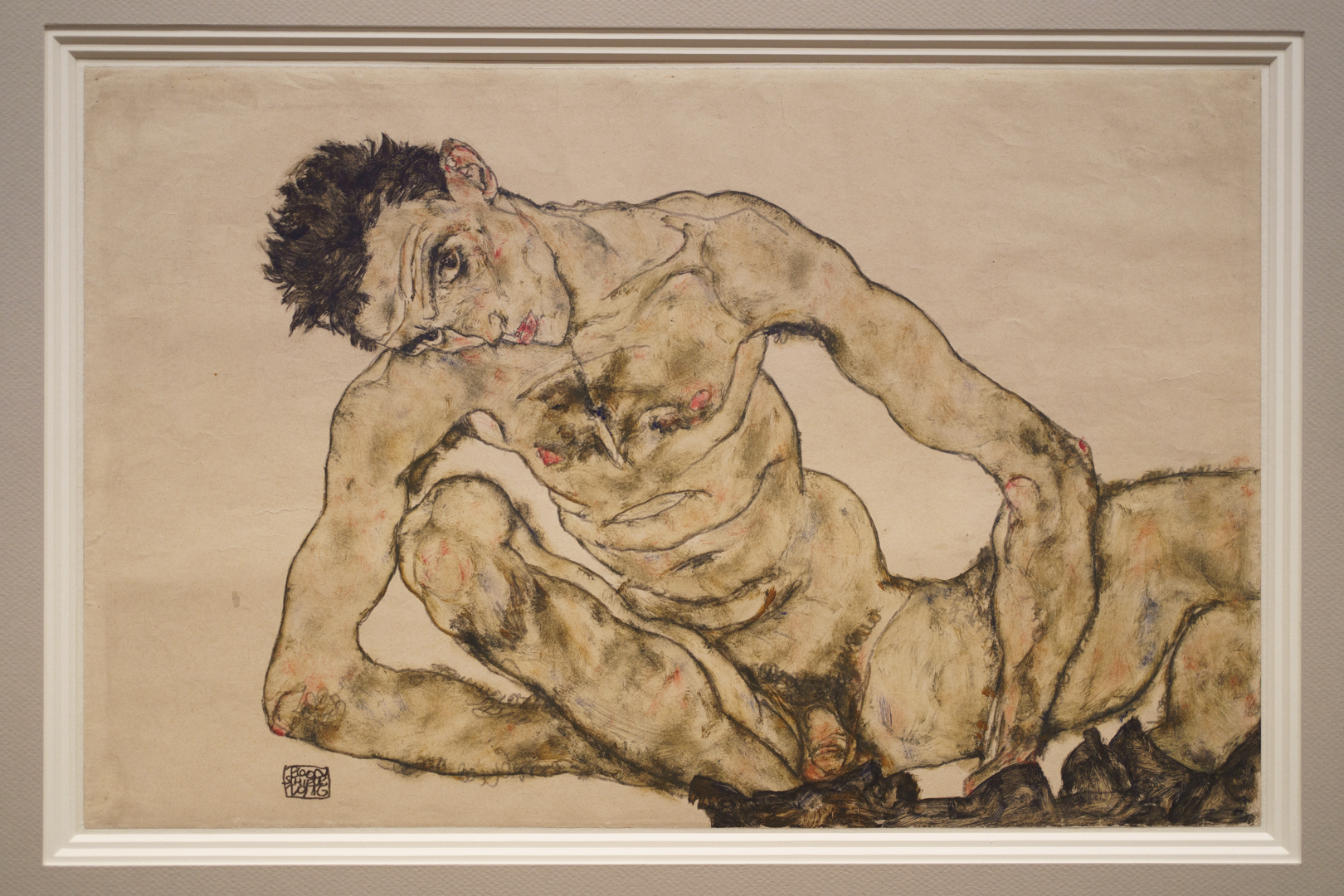

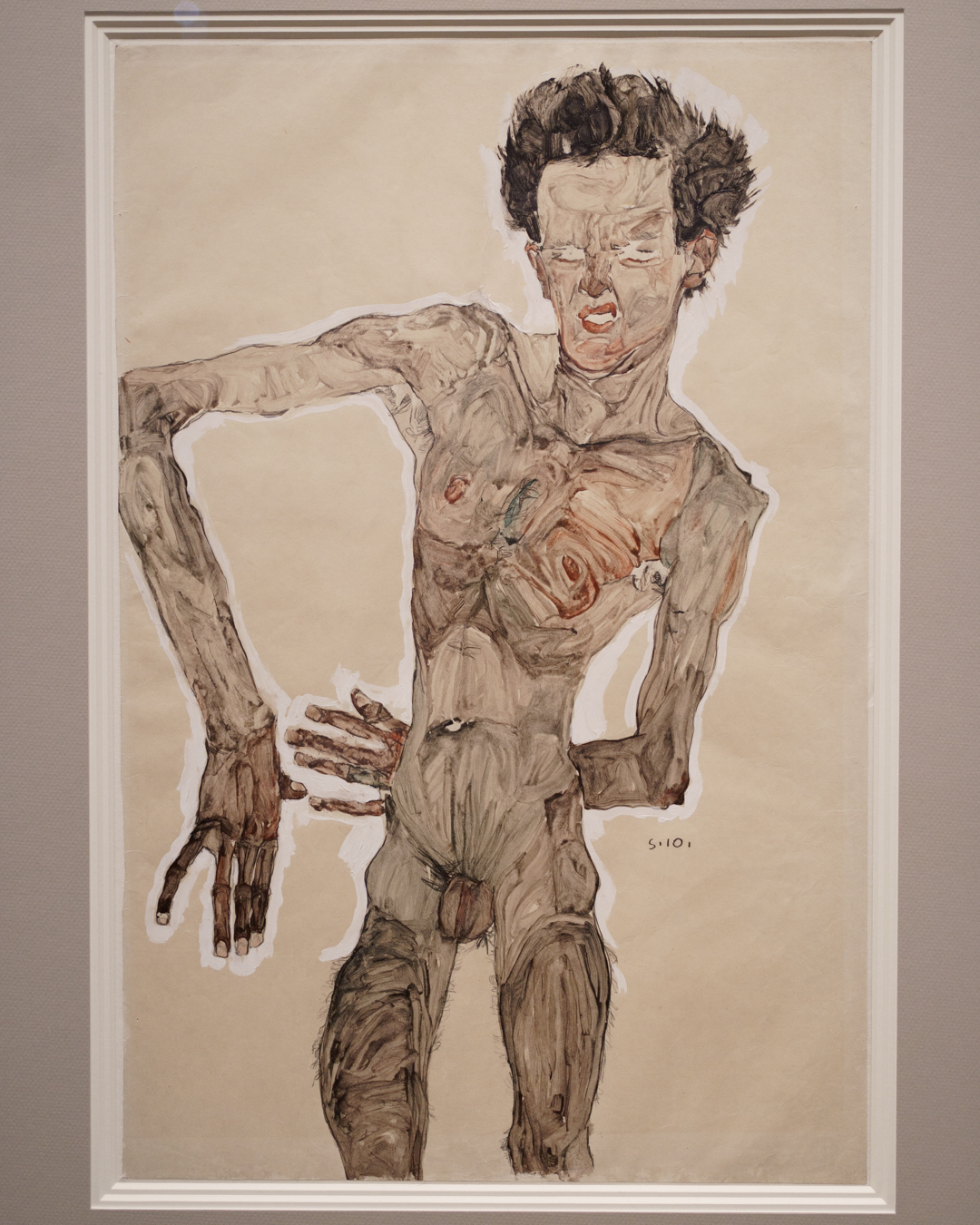

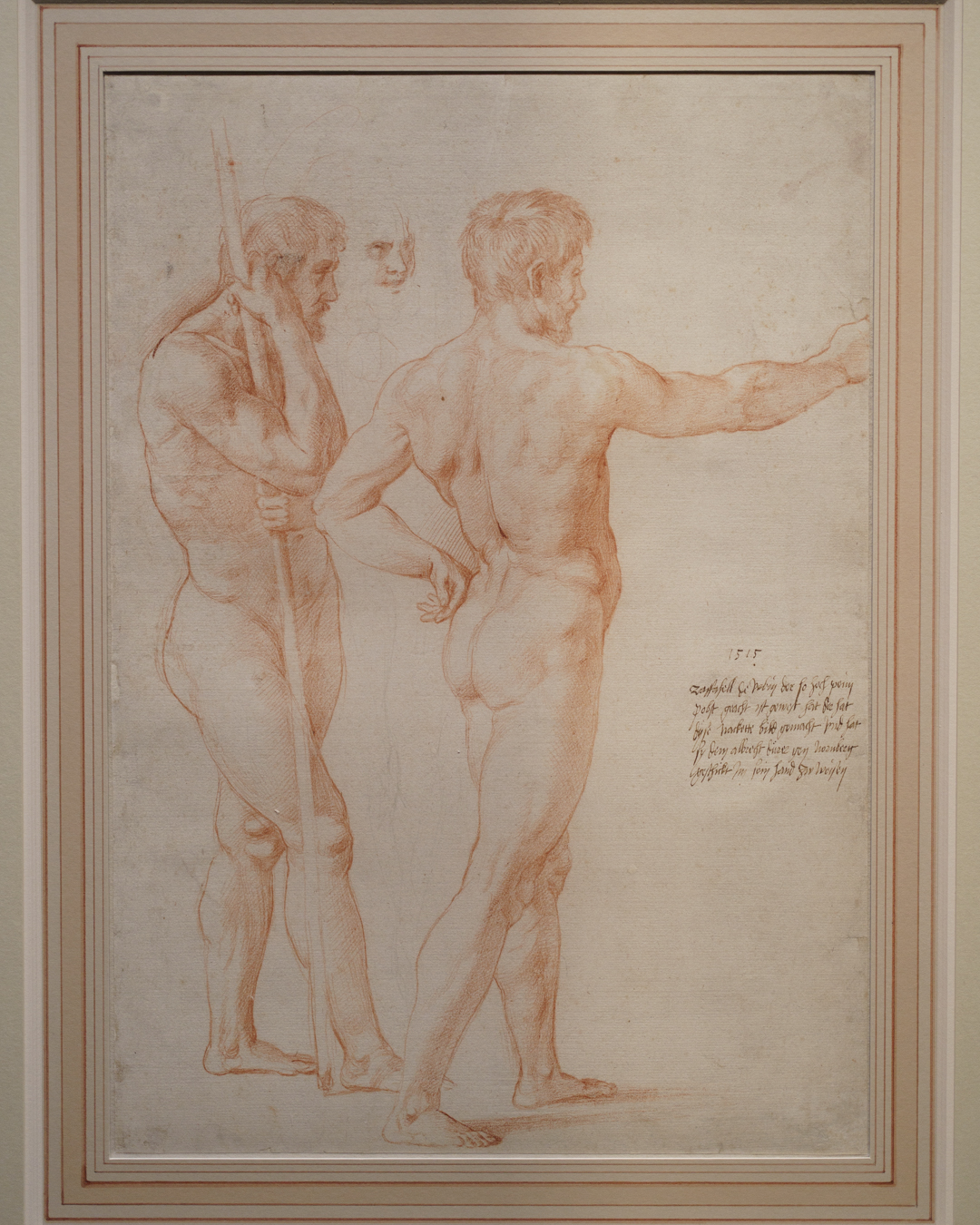

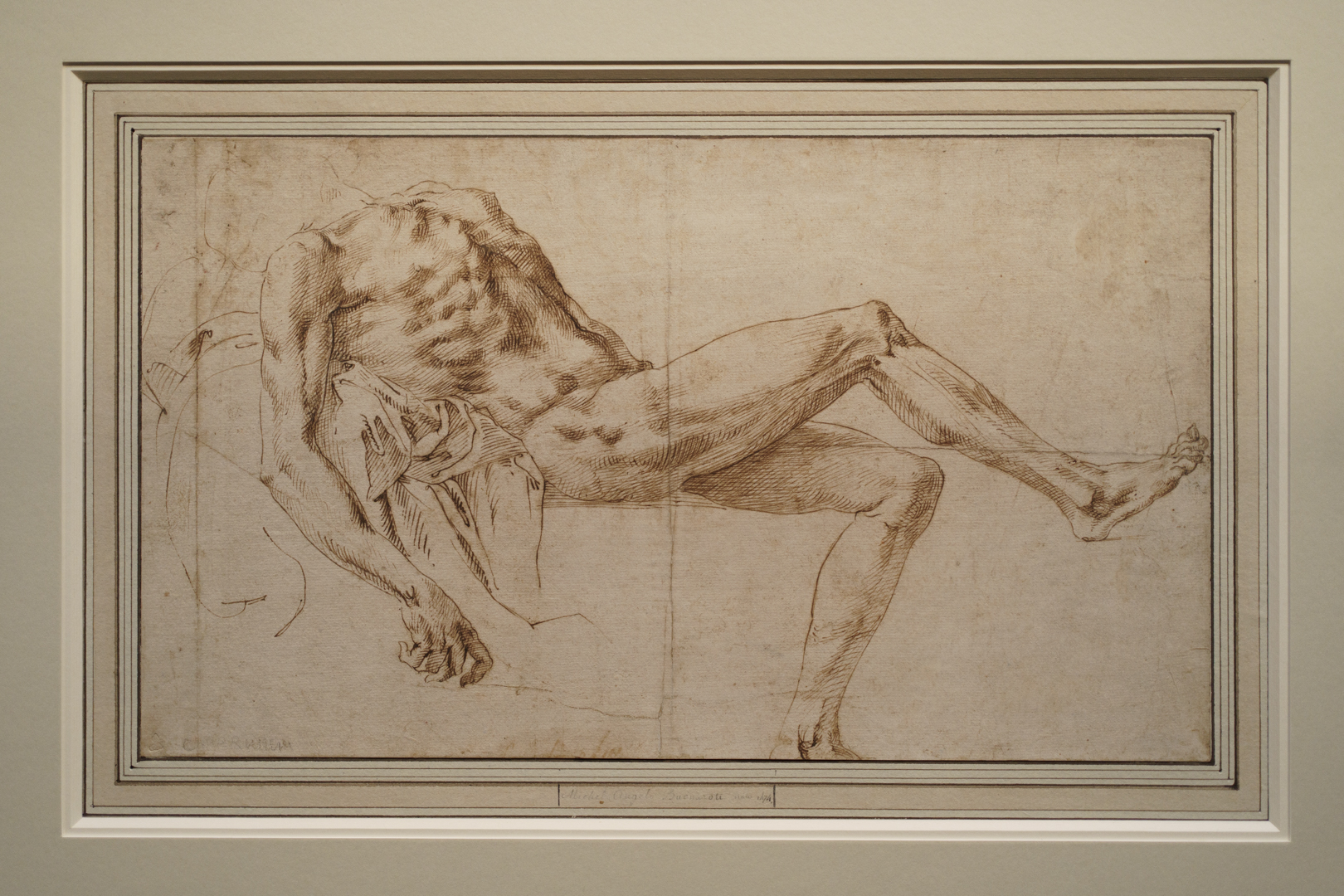

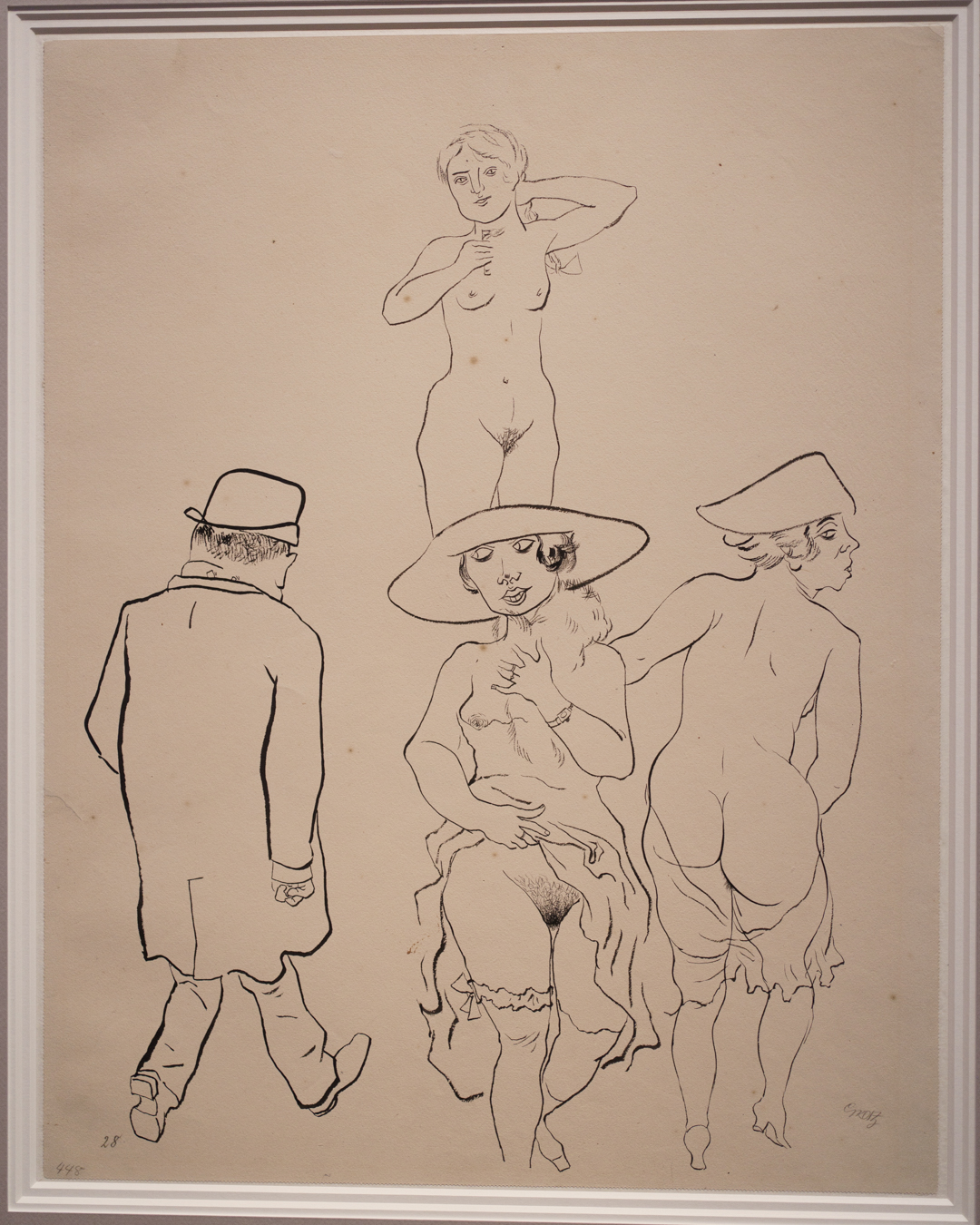

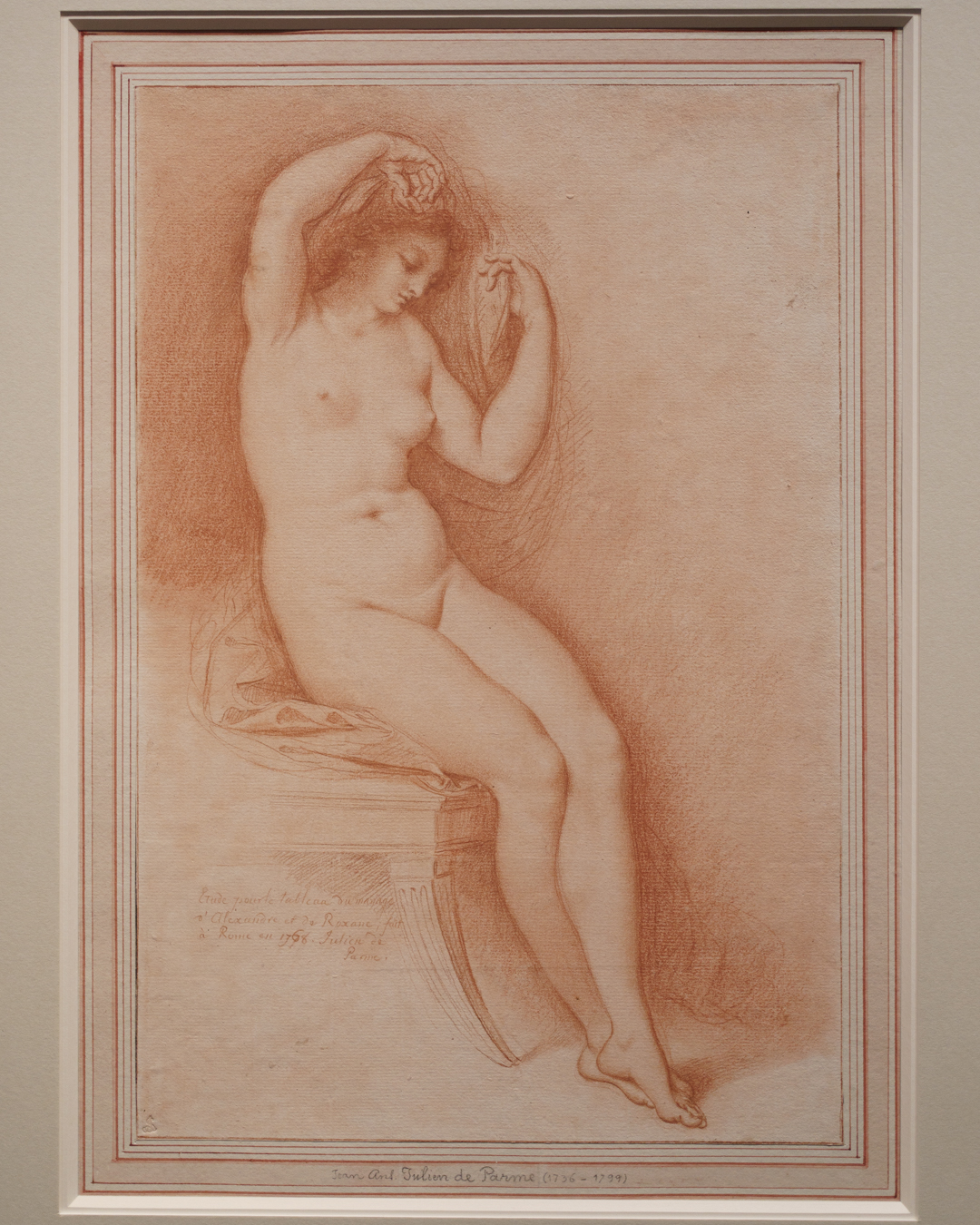

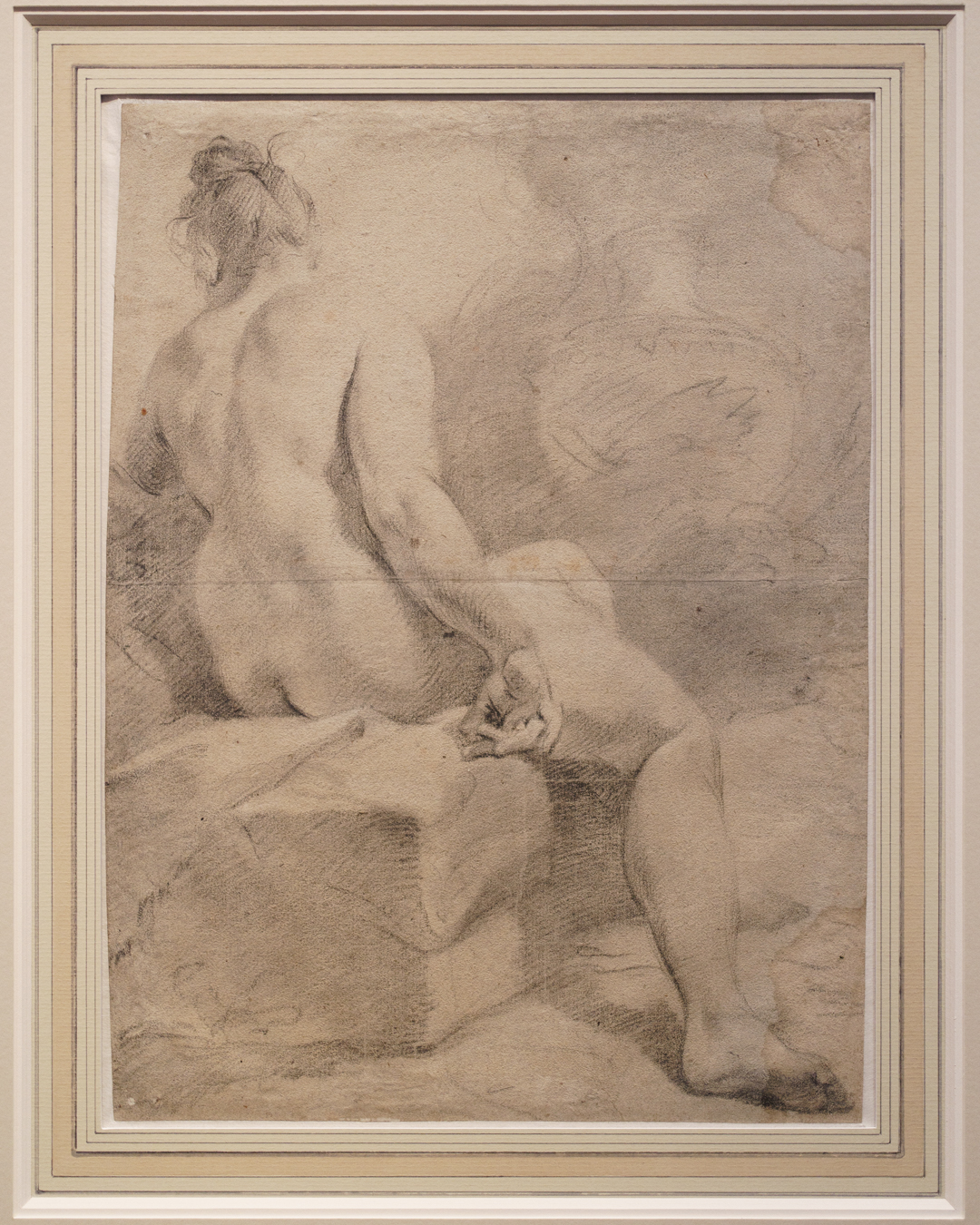

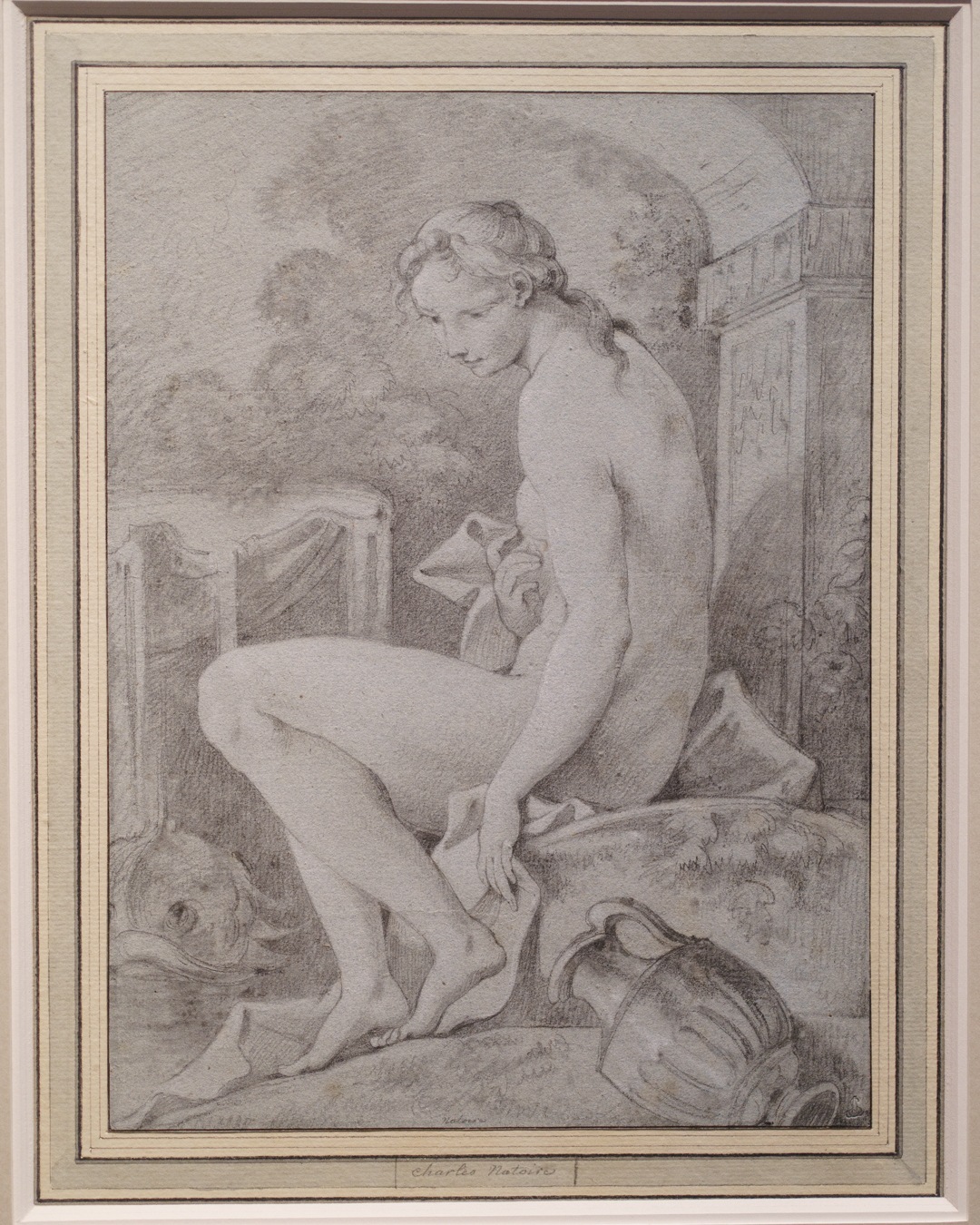

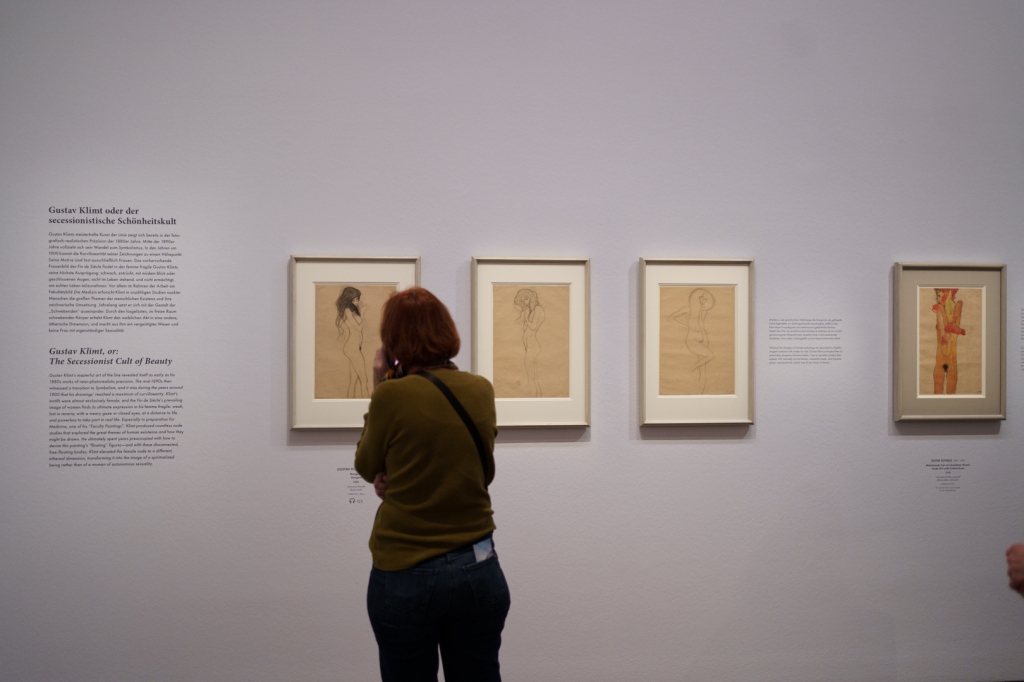

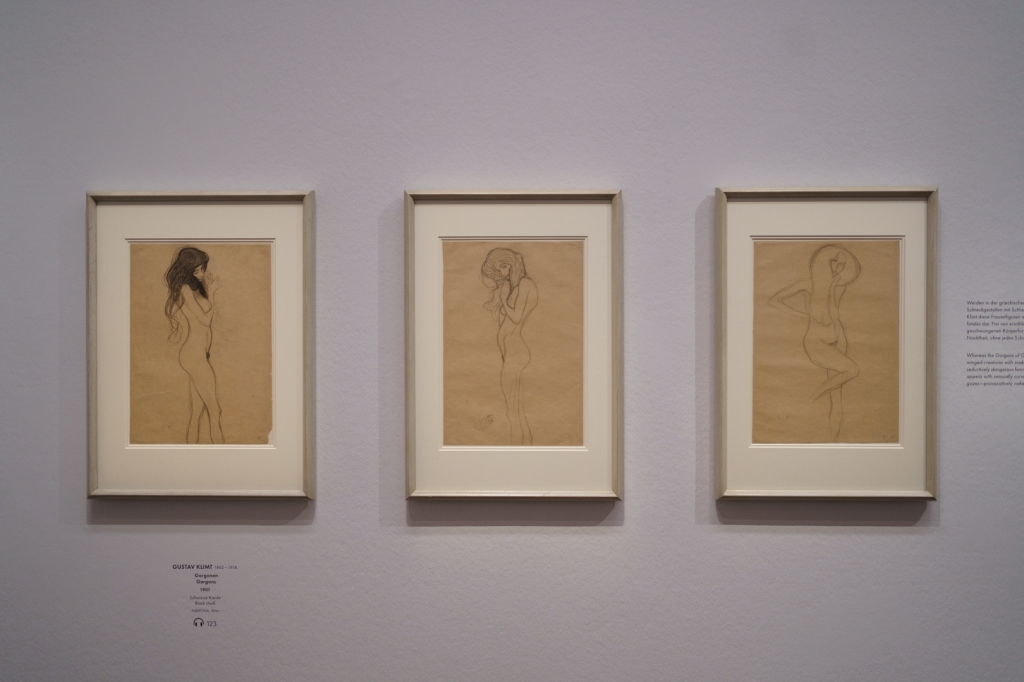

In the last room (Room 8) devoted to Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, one witnesses the radical shift from the ideal nude to the actual naked body. The same trajectory is condensed for female nudes into a single room (Room 7), poignantly highlighting the shock and sinfulness of seeing/being an immodest woman. Life studies from Peter Paul Rubens and the Carracci to Pompeo Batoni and François Boucher expertly bring the two lofty ideals back down to earth with the reality of the creative process (Room 5); Raphael’s studies for the Transfiguration and Battle of Ostia (which he sent to Albrecht Dürer) would have shined here instead of a partial solo presentation in Room 3 with two outstanding studies for the Fire in the Borgo.

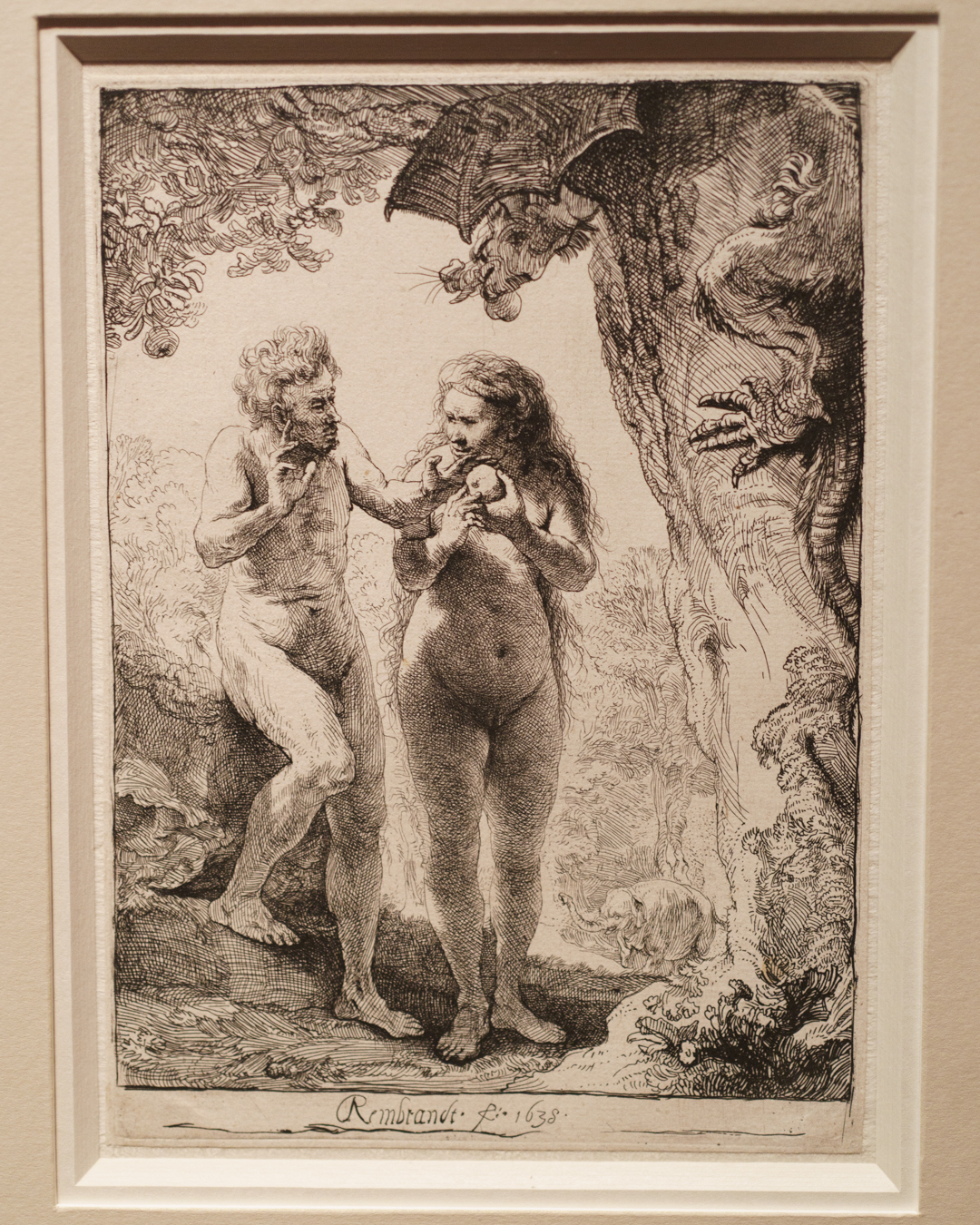

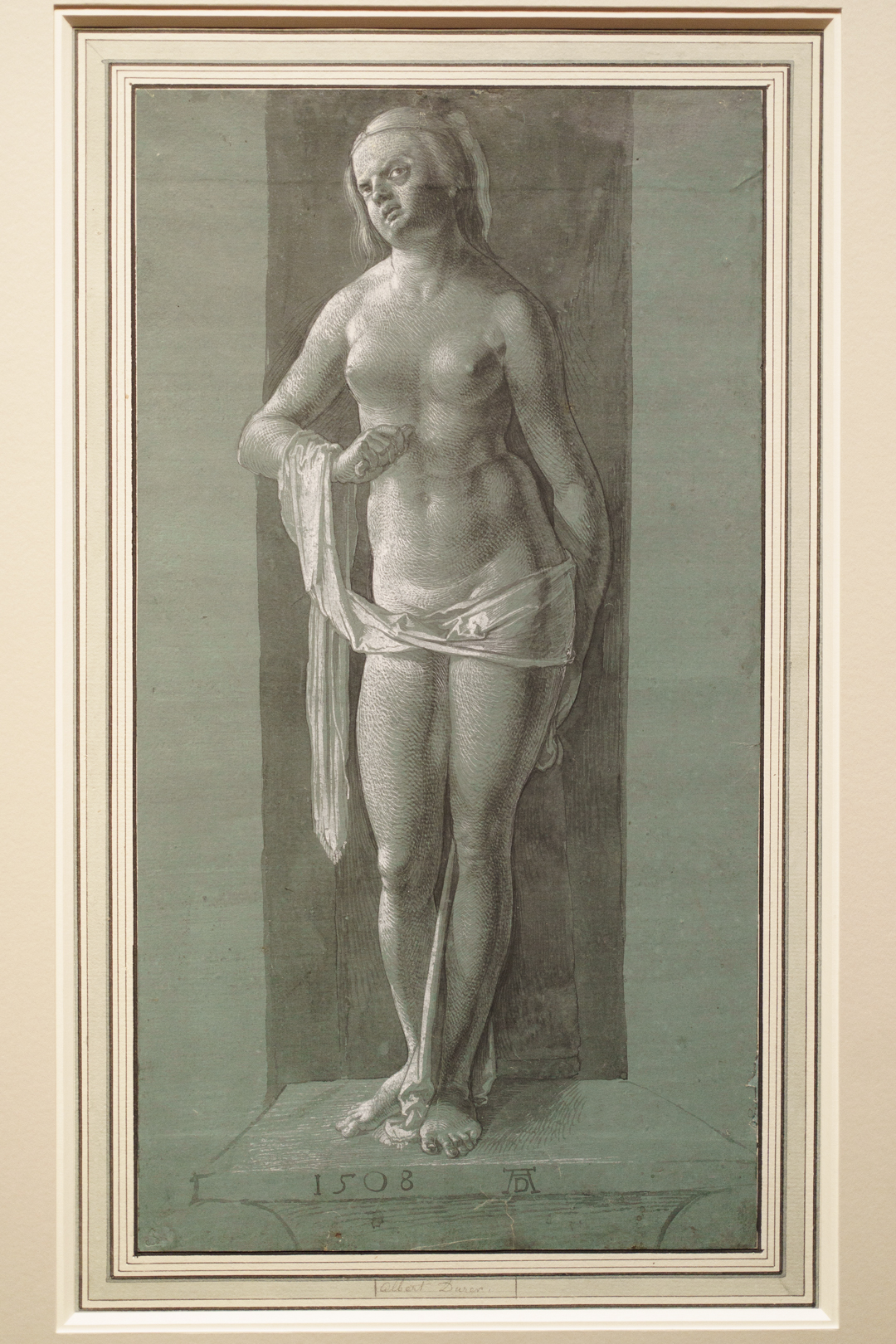

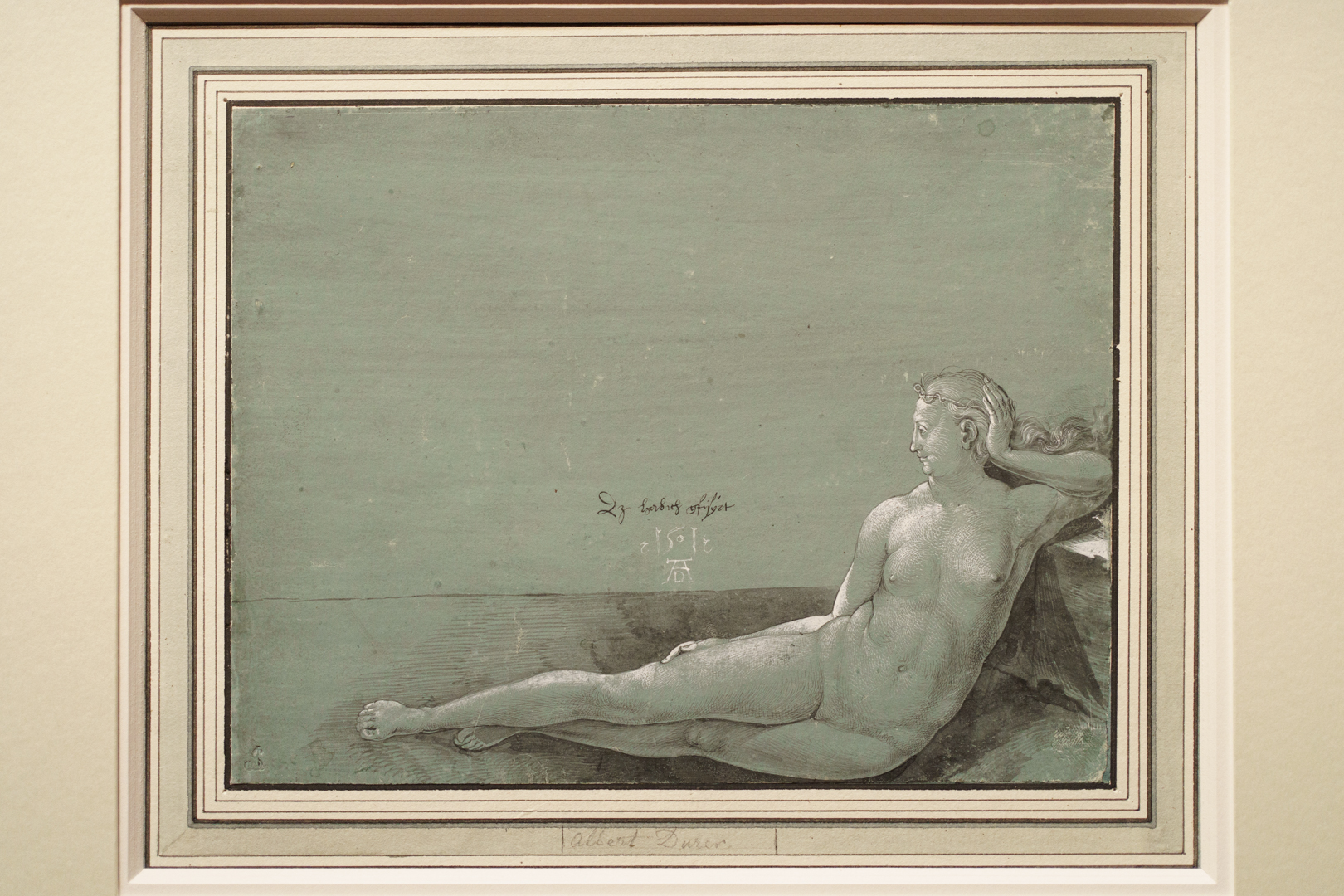

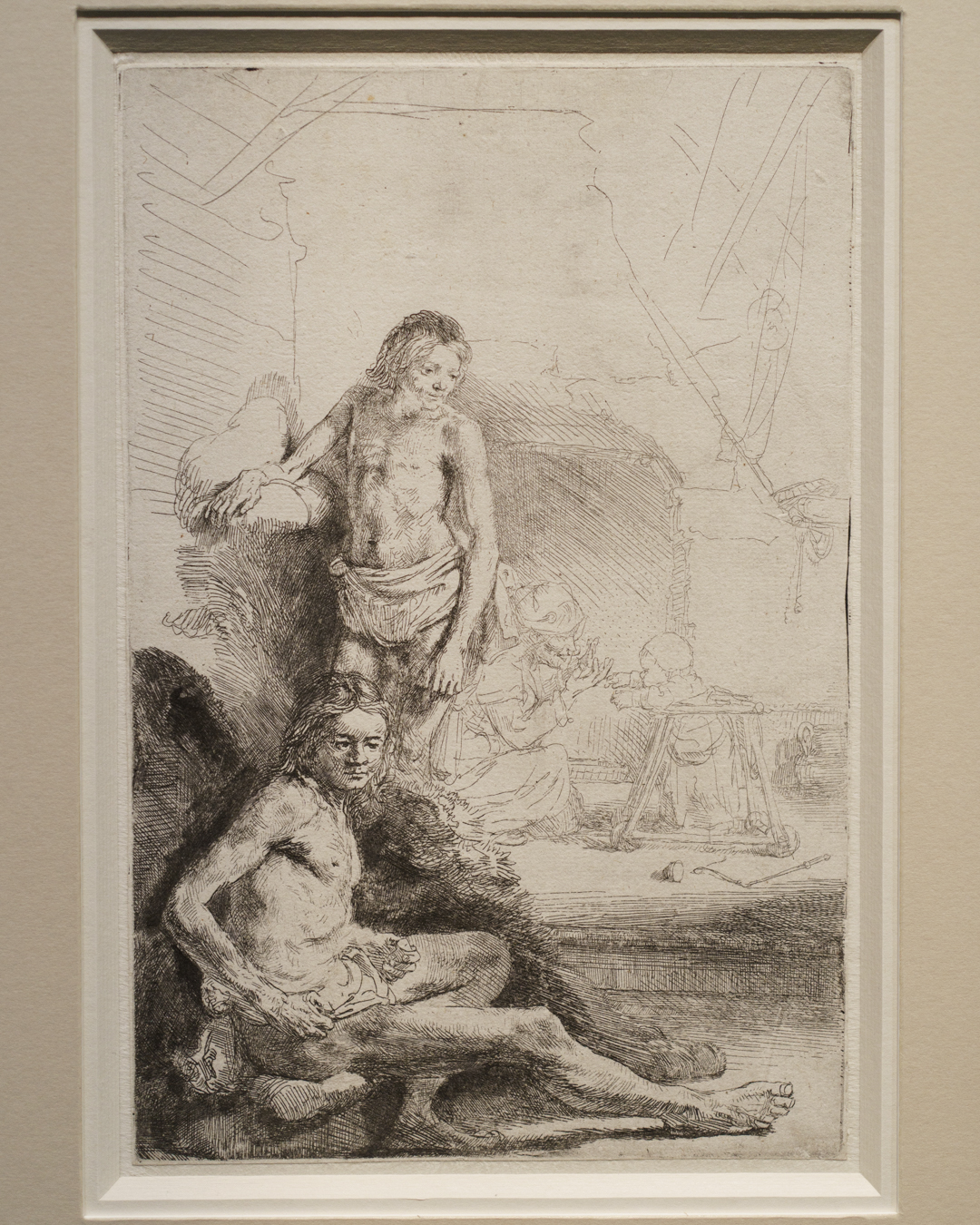

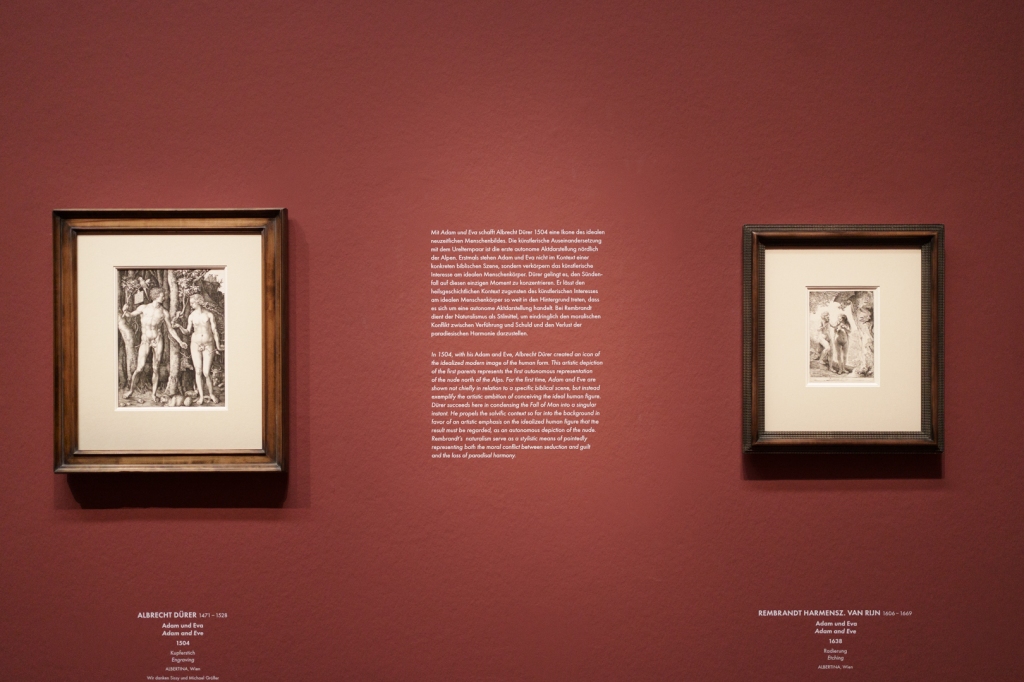

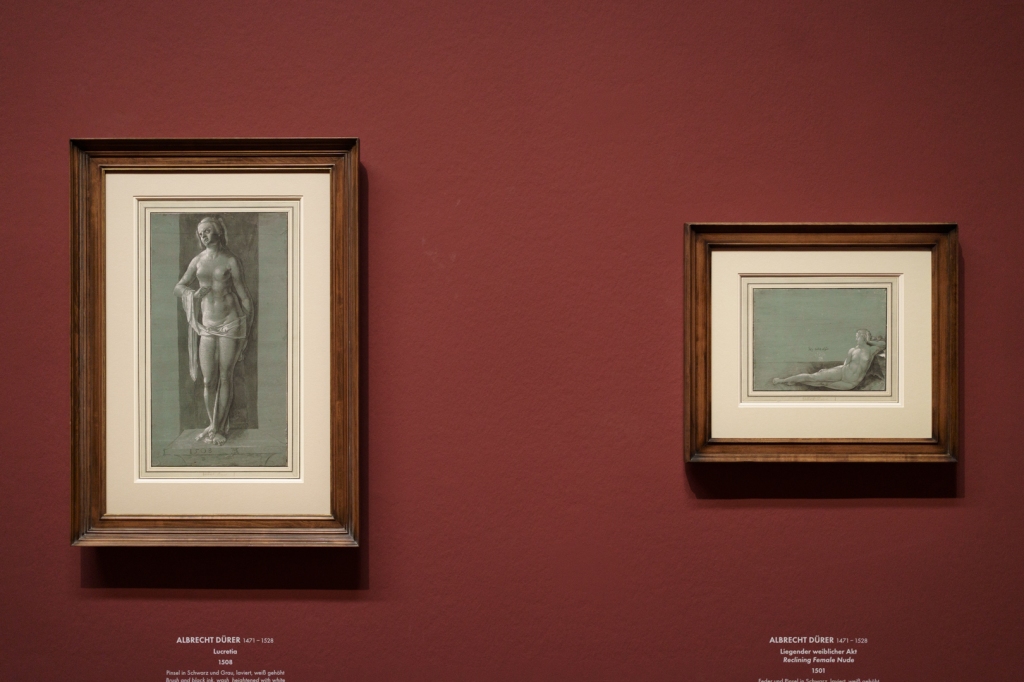

Off to the side, the small Dürer room (Room 6) flips these ideals on their heads by exploring grotesque female bodies in Baldung Grien’s drawings of witches. This one-sided analysis would have considerably enlarged its scope of discussion had an Italianate example been included, such as Agostino Veneziano’s Lo Stregozzo engraving. This room also eloquently brings the two sexes together with Dürer’s studies for the Adam and Eve engraving, itself paired with Rembrandt’s own treatment of the subject.

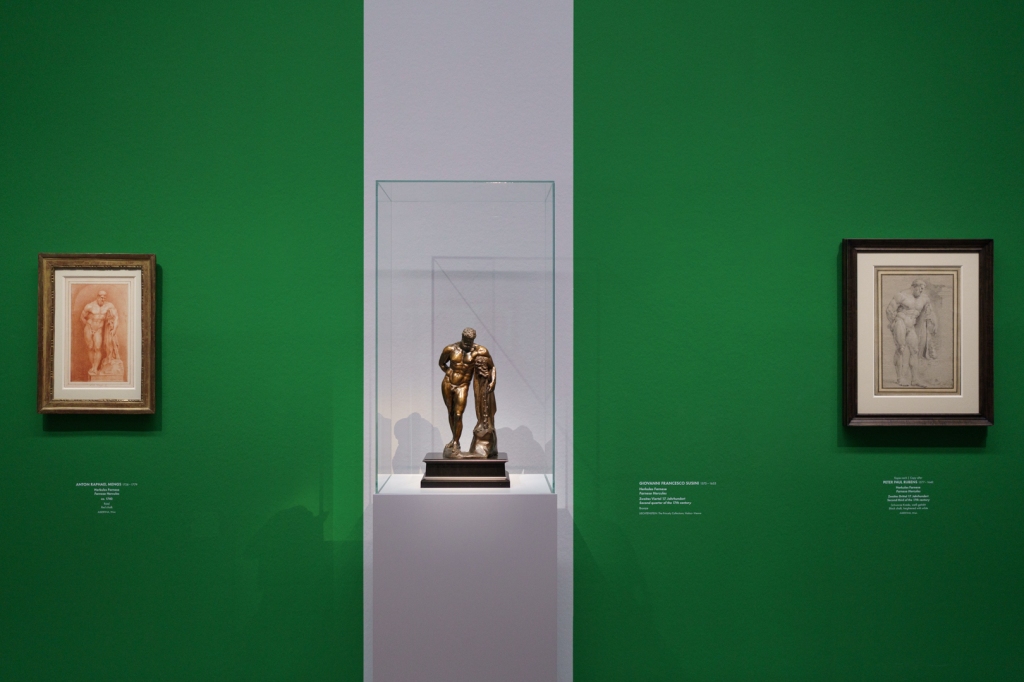

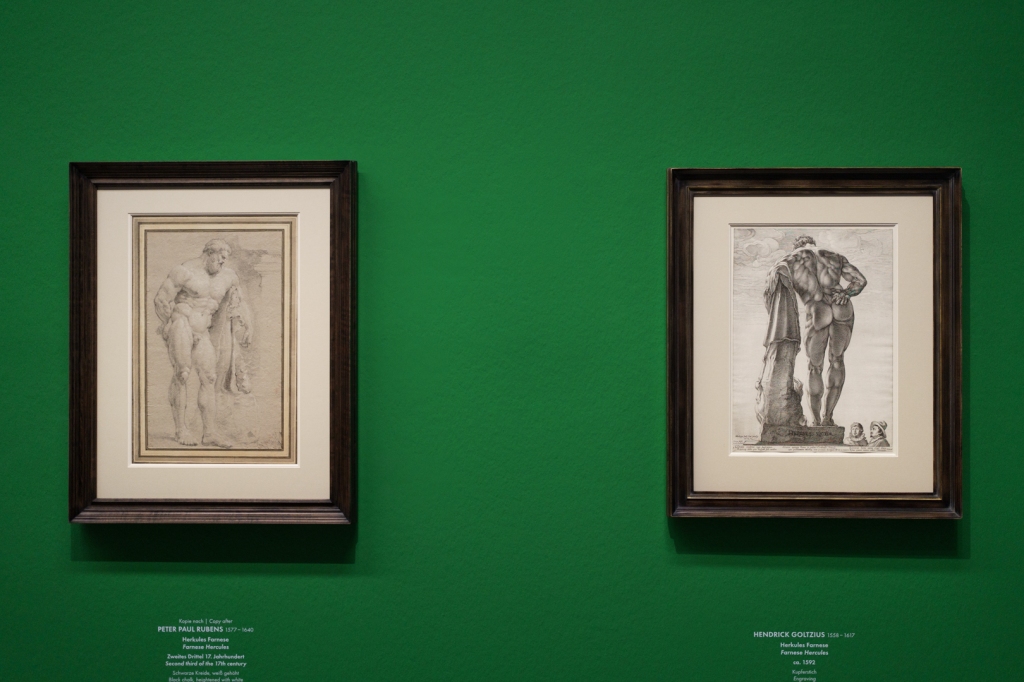

Amidst big names like Raphael, Rubens, and Rembrandt, it is really the lesser names that offered the greatest topics of interest. The wondrous loan of sculptures from the Palais Liechtenstein collection proved crucial to some of these comparisons.

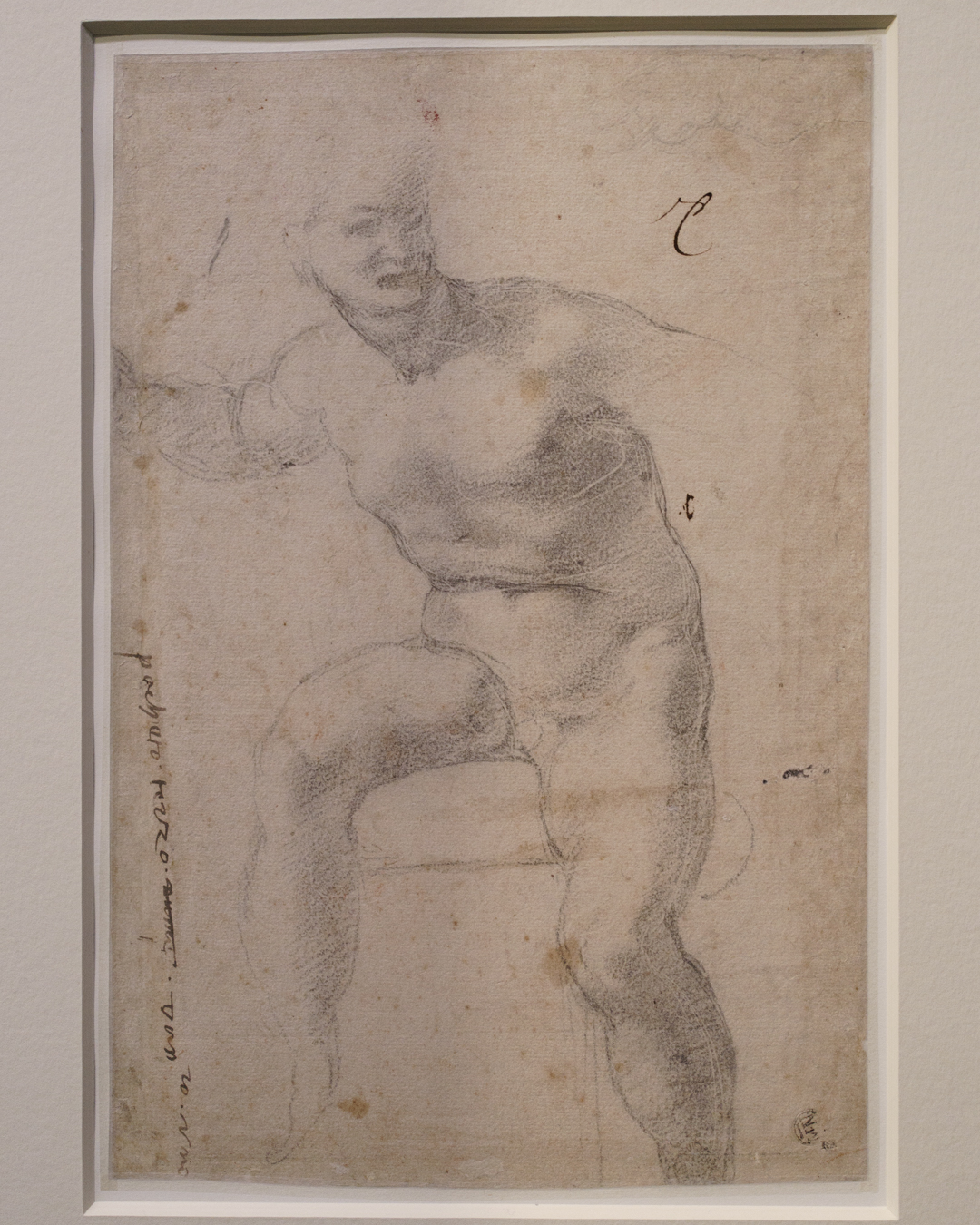

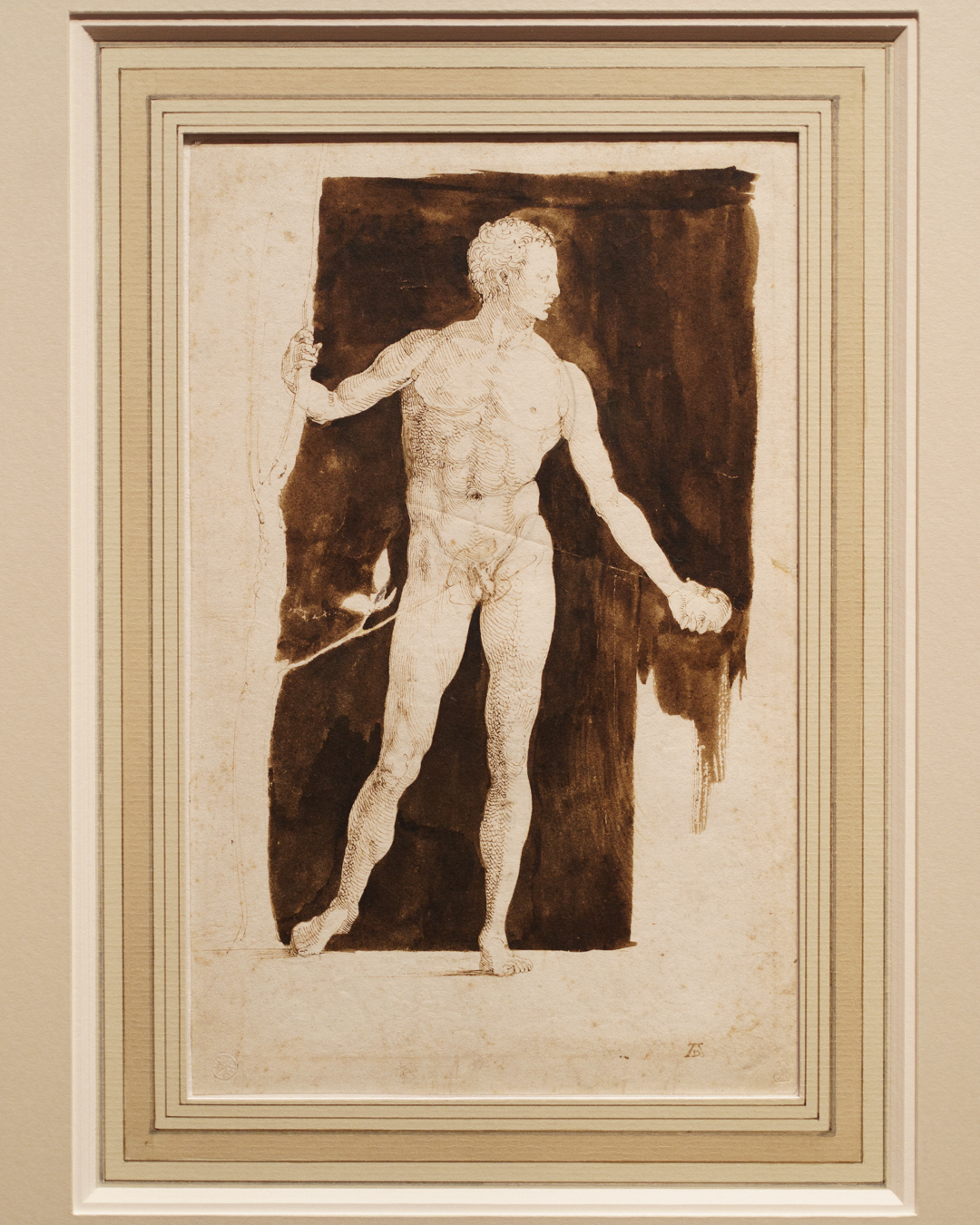

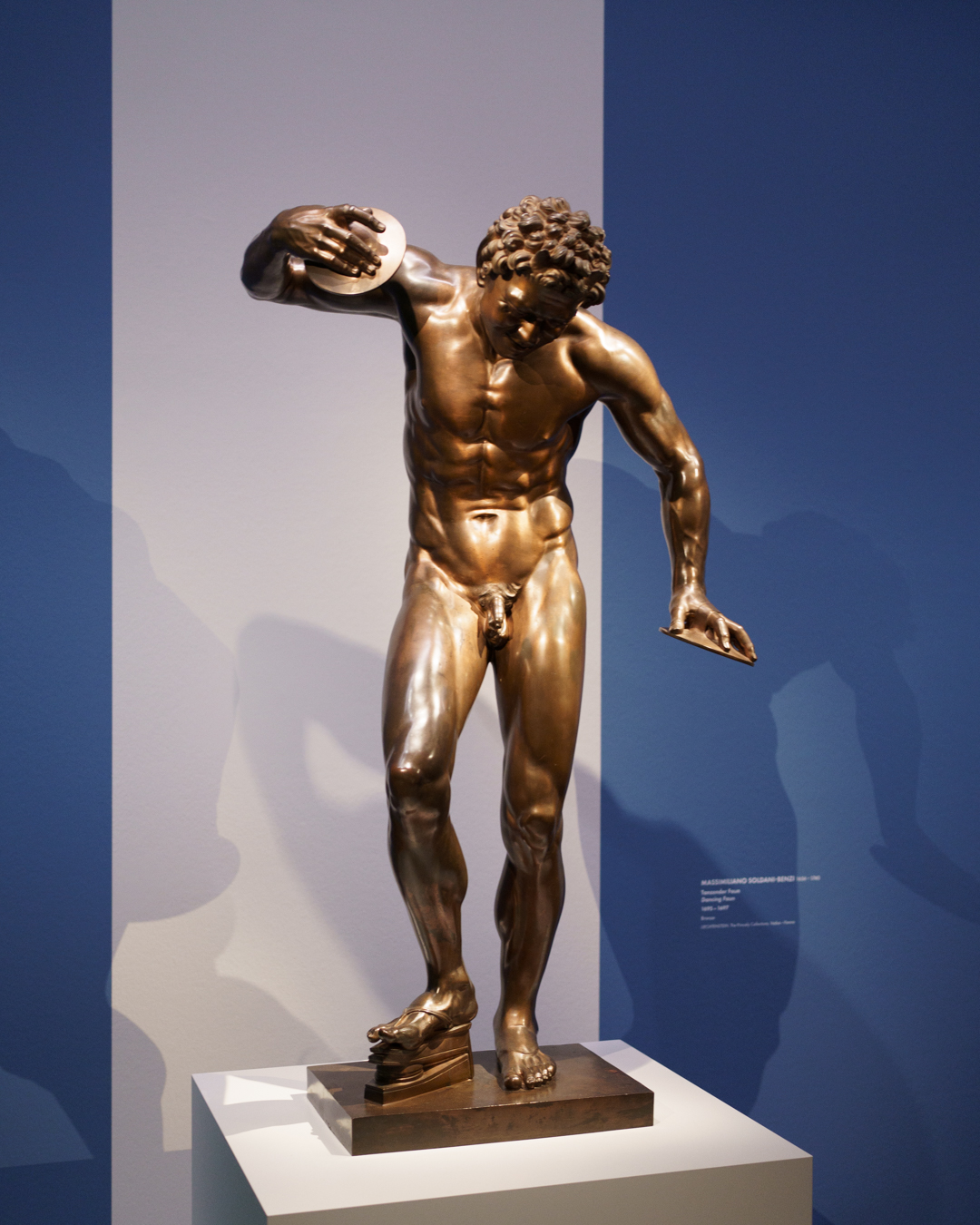

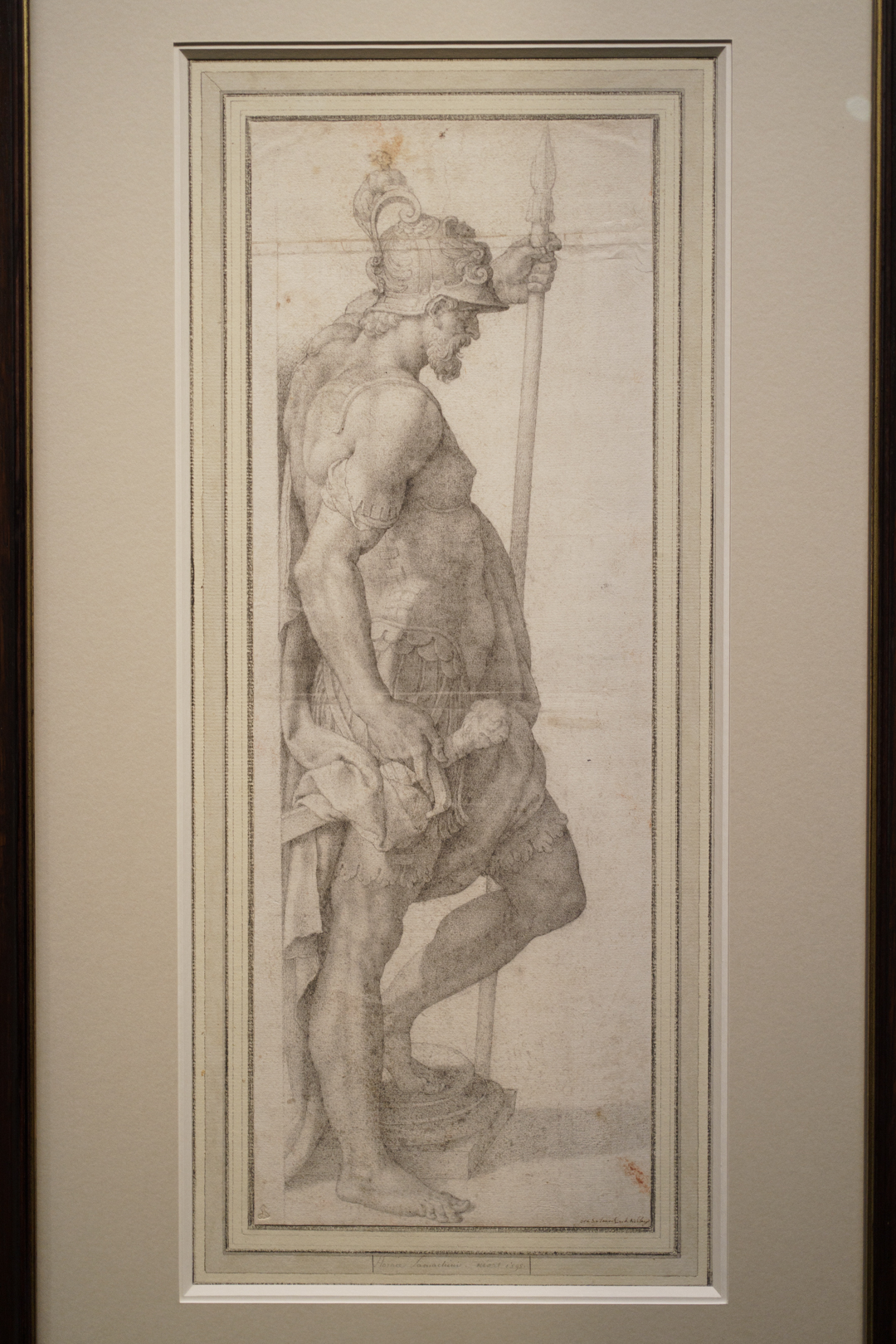

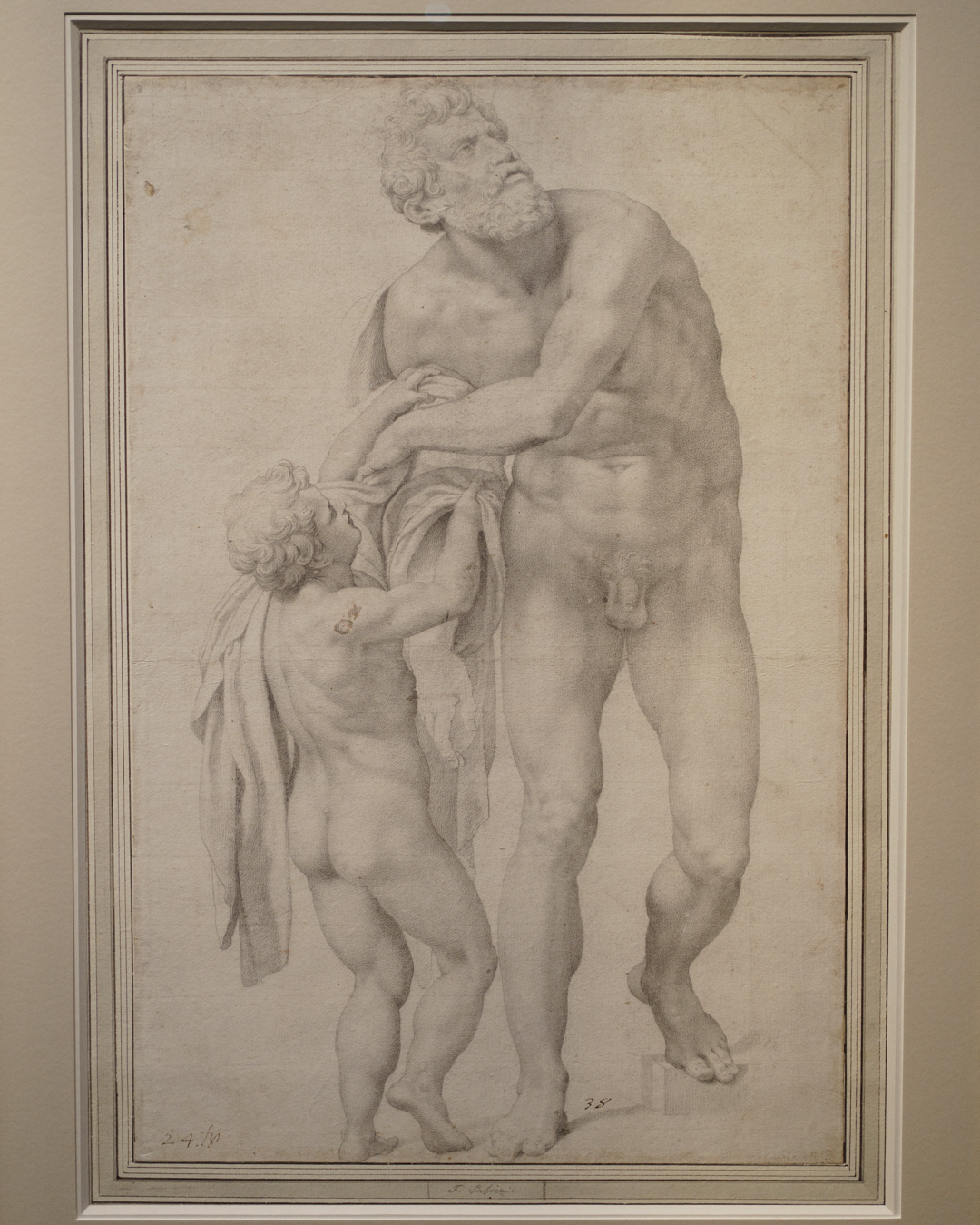

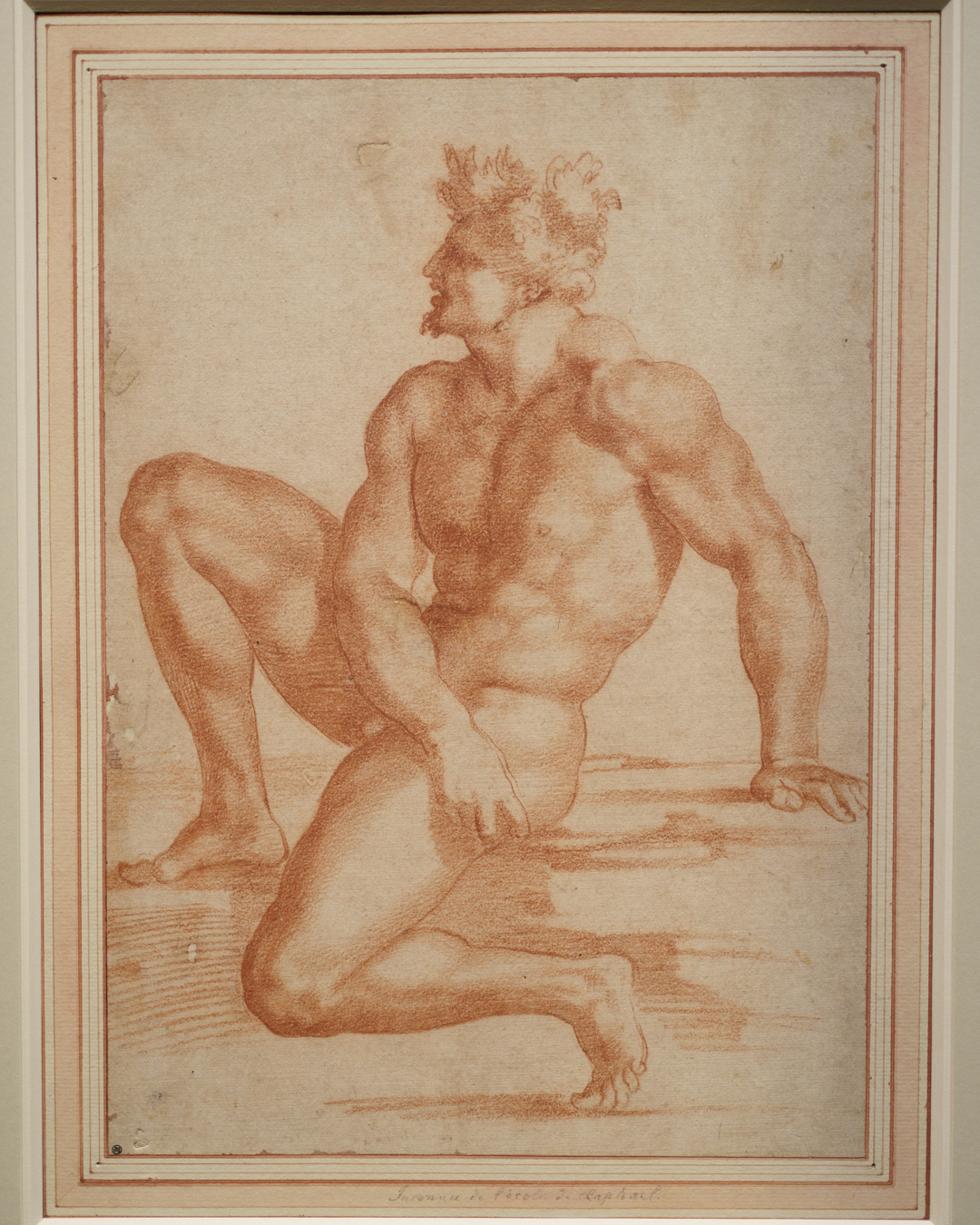

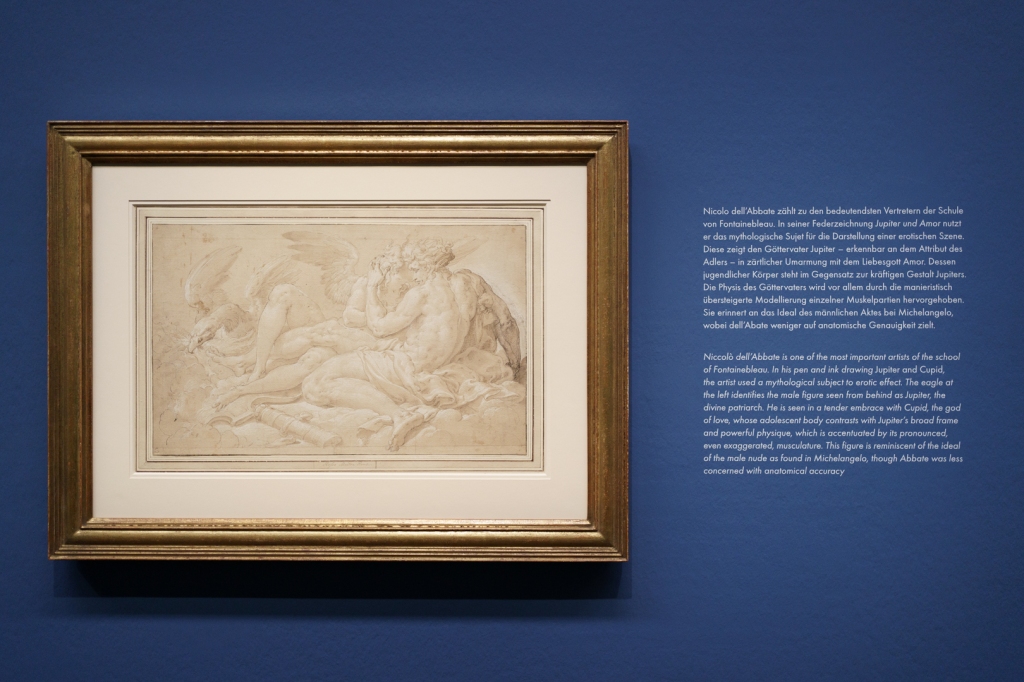

Visually evident (but unmentioned) was a powerful grouping of figures in contrapposto (Room 3), consisting of Francesco Salviati’s drawn copy of Michelangelo’s Apollo-David (Bargello, Florence), a bronze cast of the antique Dancing Faun, Livio Agresti’s drawing of a standing warrior, and Daniele da Volterra of Aeneas with a boy. The same can be said for the seated male nudes depicted by Domenico Beccafumi, Baccio Bandinelli, and Niccolò dell’Abbate. These quickly outshined the Raphael drawings in the same room.

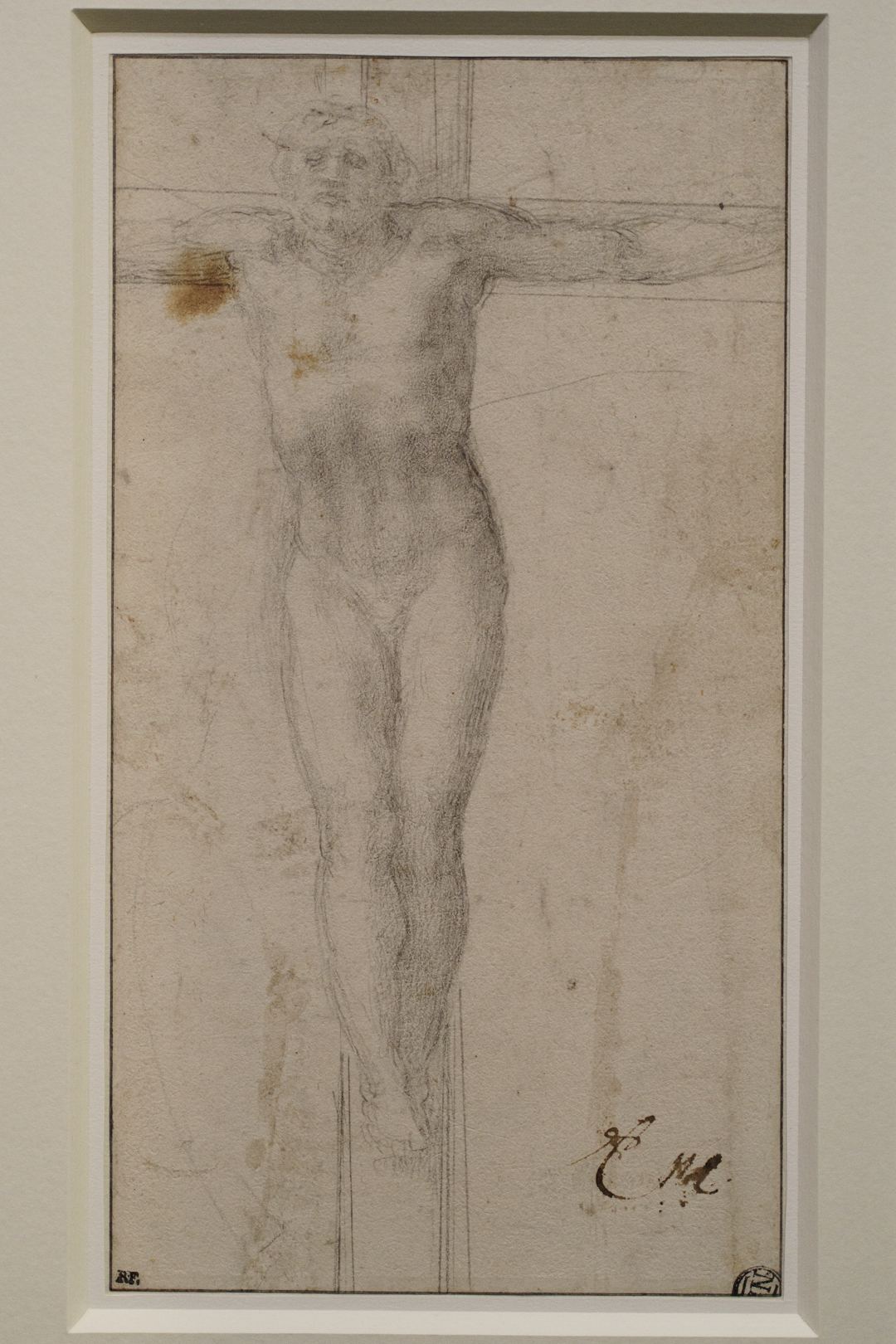

In Room 2, a magnificent cast of Michelangelo’s Pietà (St Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City) paved the way for a stunning dialogue between his late Pietà drawings and those of a dead Christ by Rosso Fiorentino and Battista Franco. One could almost see them as direct copies of the sculpture. Furthermore, Franco’s confident and delicate application of line is entrancing when compared to Rosso’s.

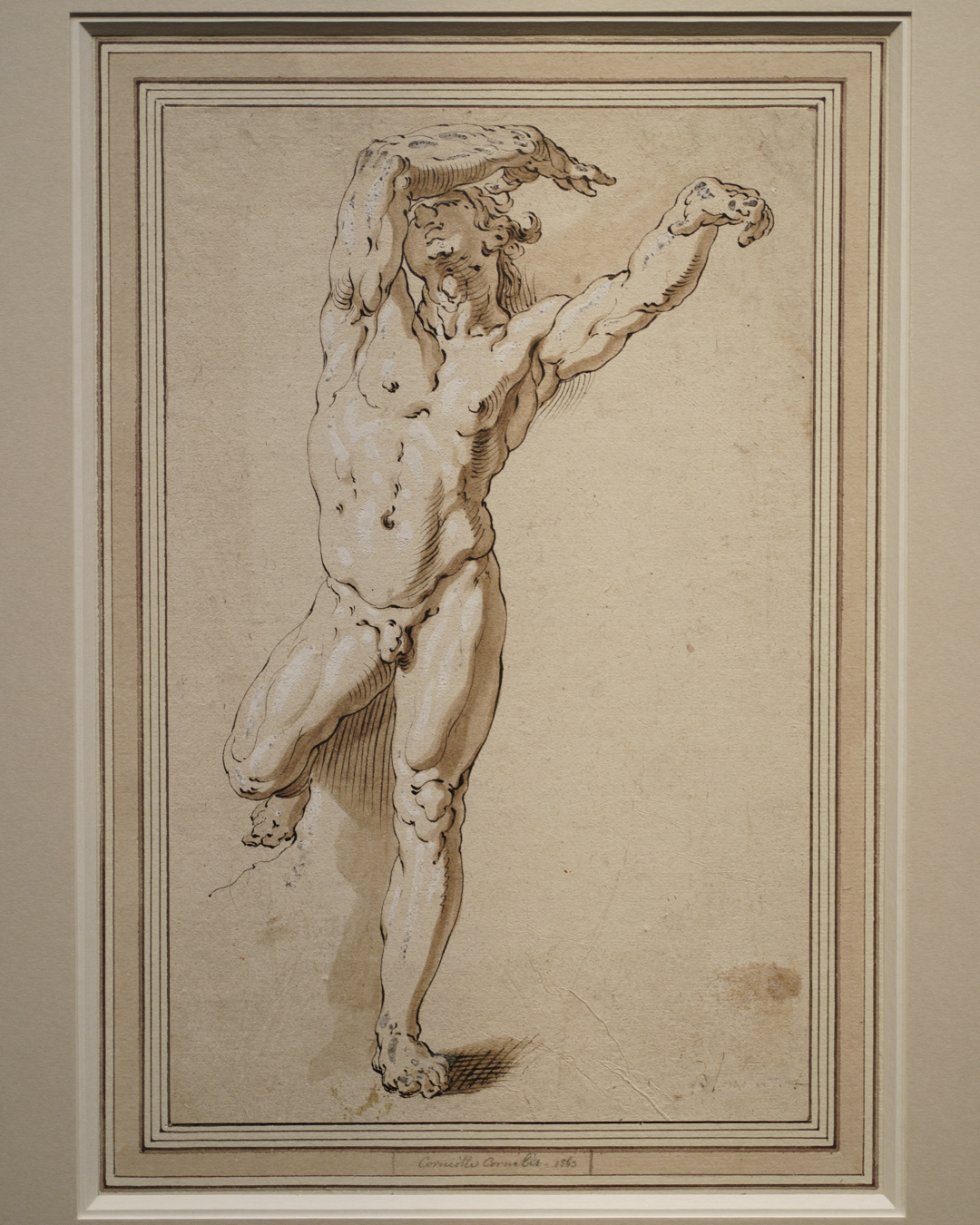

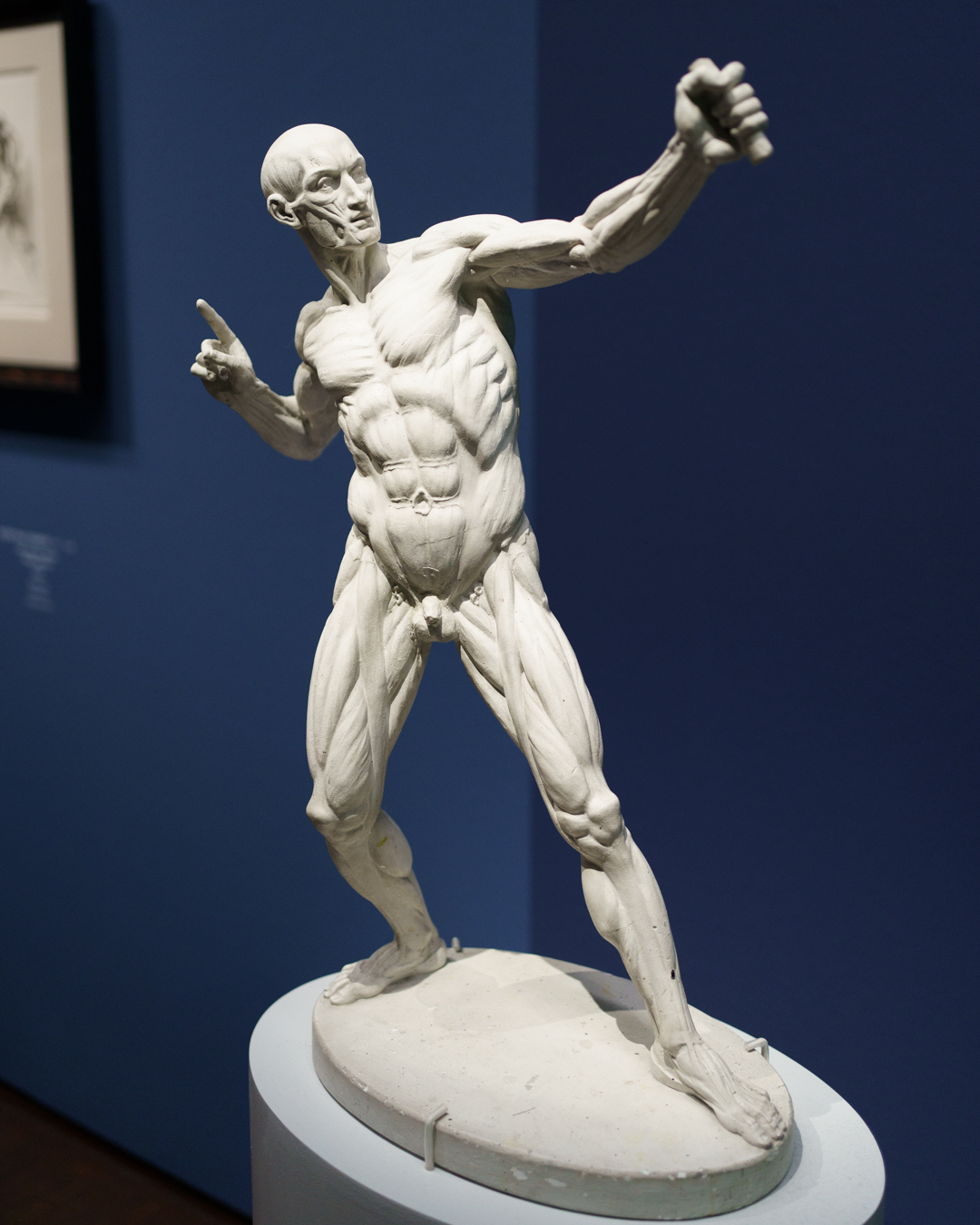

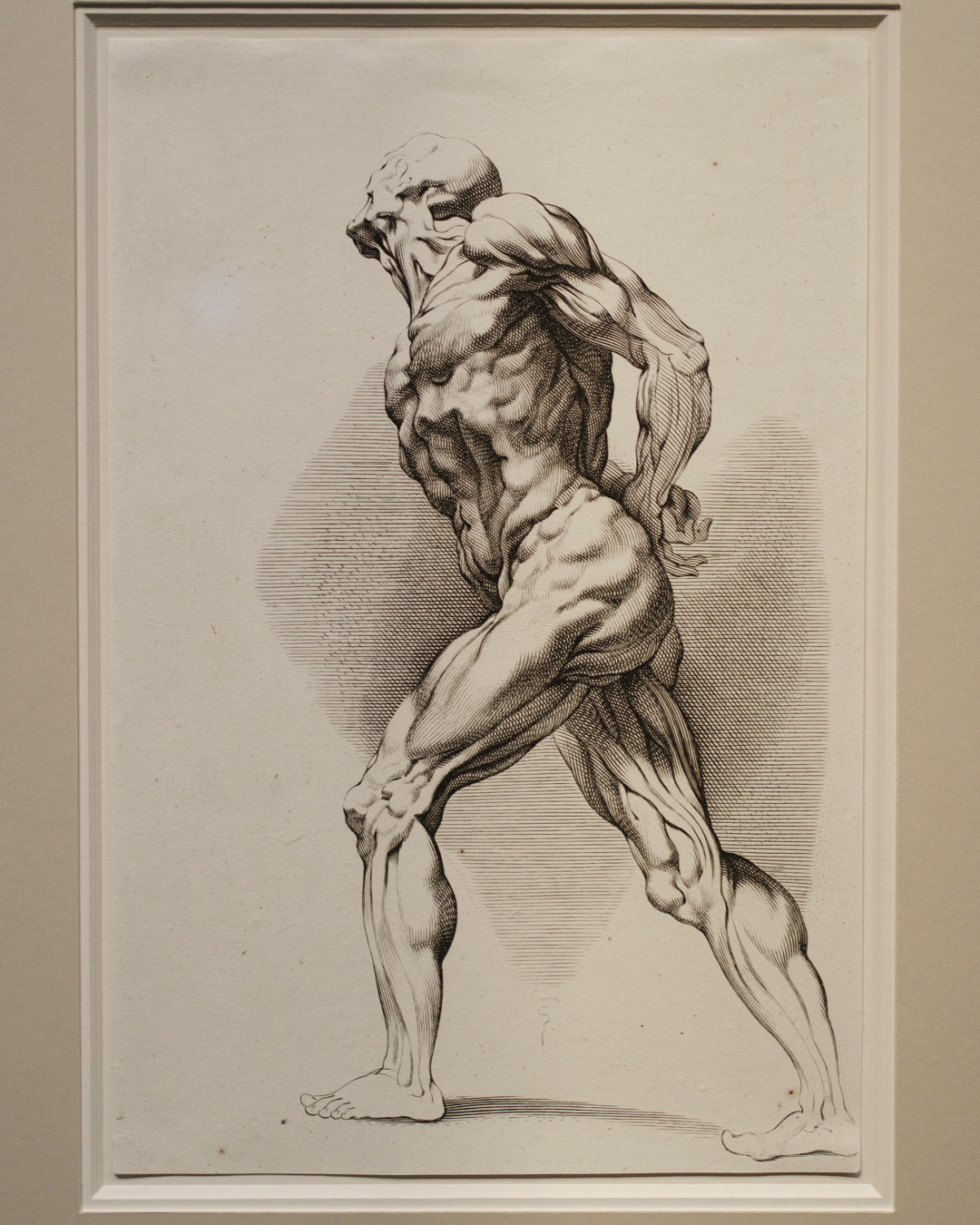

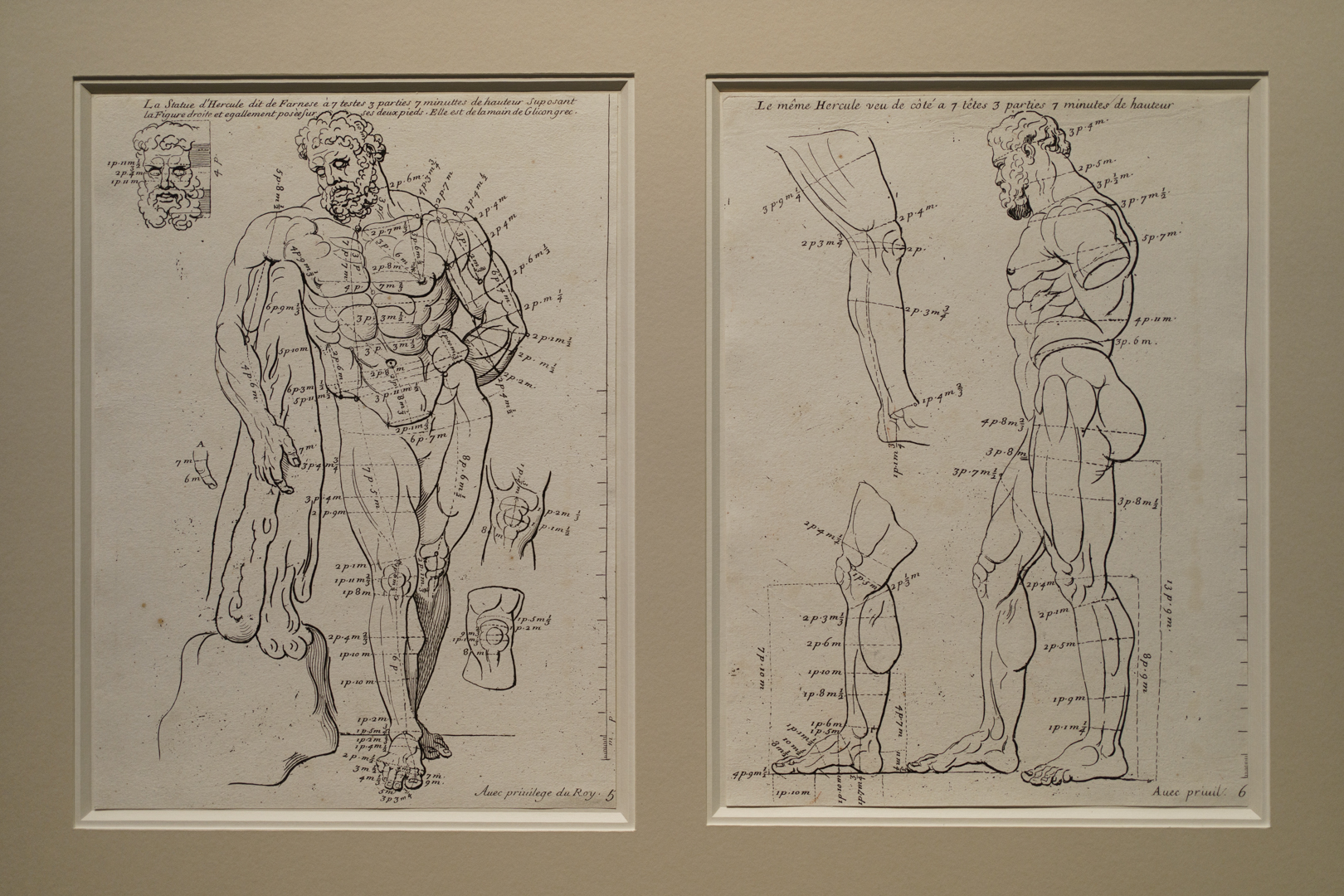

Going against the grain of realism, a wall of exaggerated nudes in Room 4 – grouped under the category of un sacco di noce (bag of nuts) – is contrasted with a section on écorché and anatomical studies, which features the last Michelangelo drawing in the show. The former is where we find one of the exhibition’s nicest unattributed drawings: a monochrome St Sebastian by a Netherlandish artist. The latter also resonates with Dürer’s studies for Adam and Eve, which were conceived on the basis of correct proportions with theological implications.

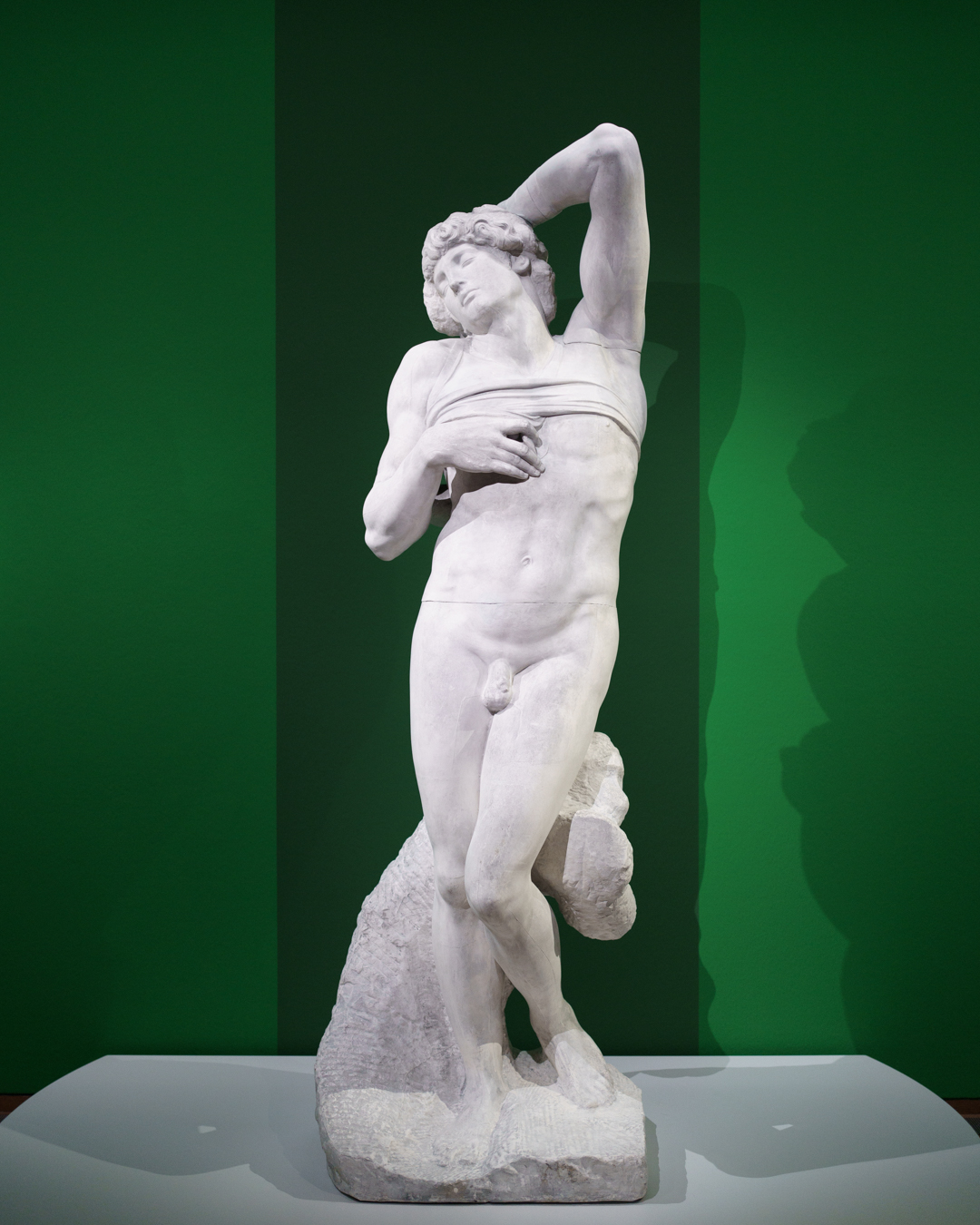

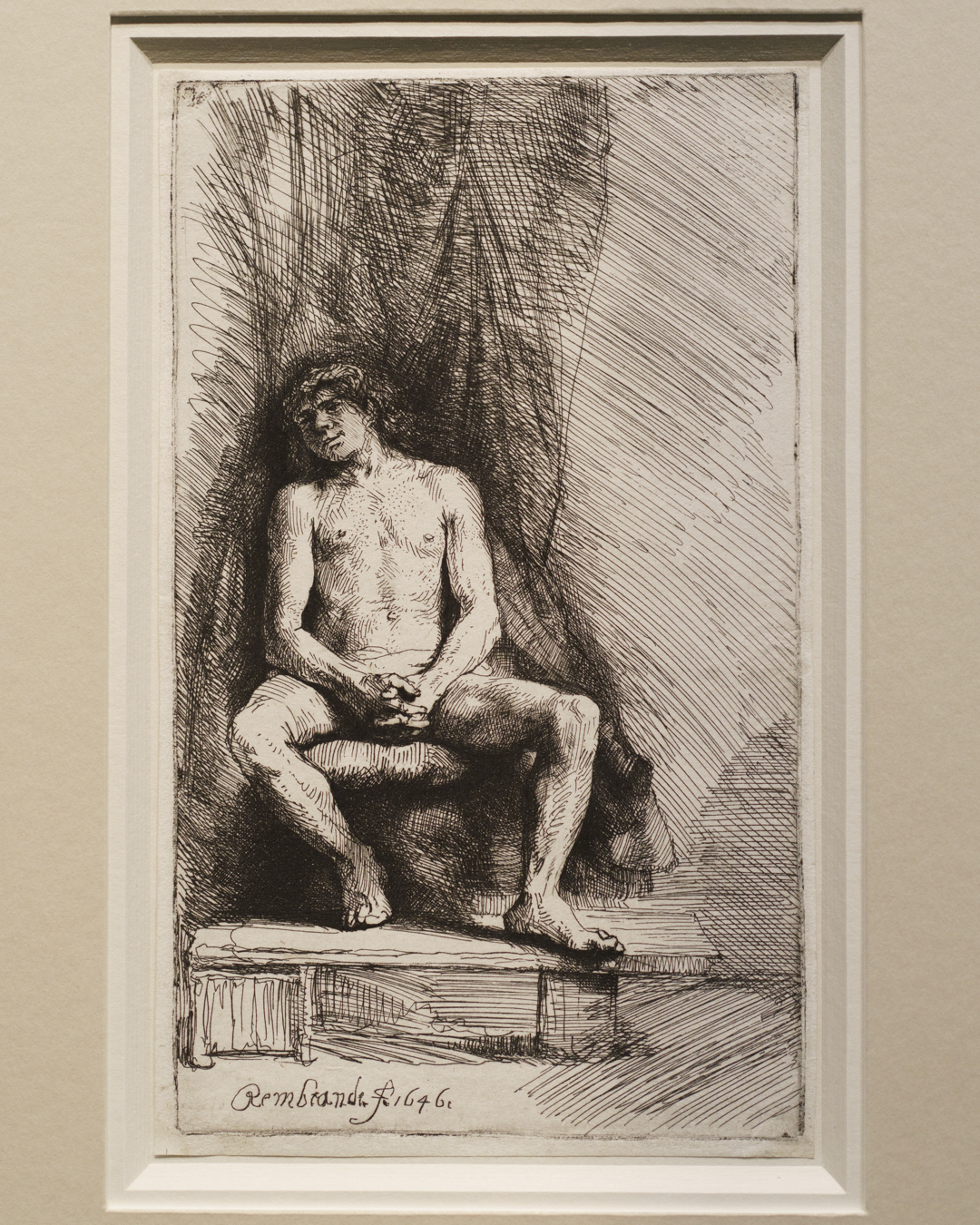

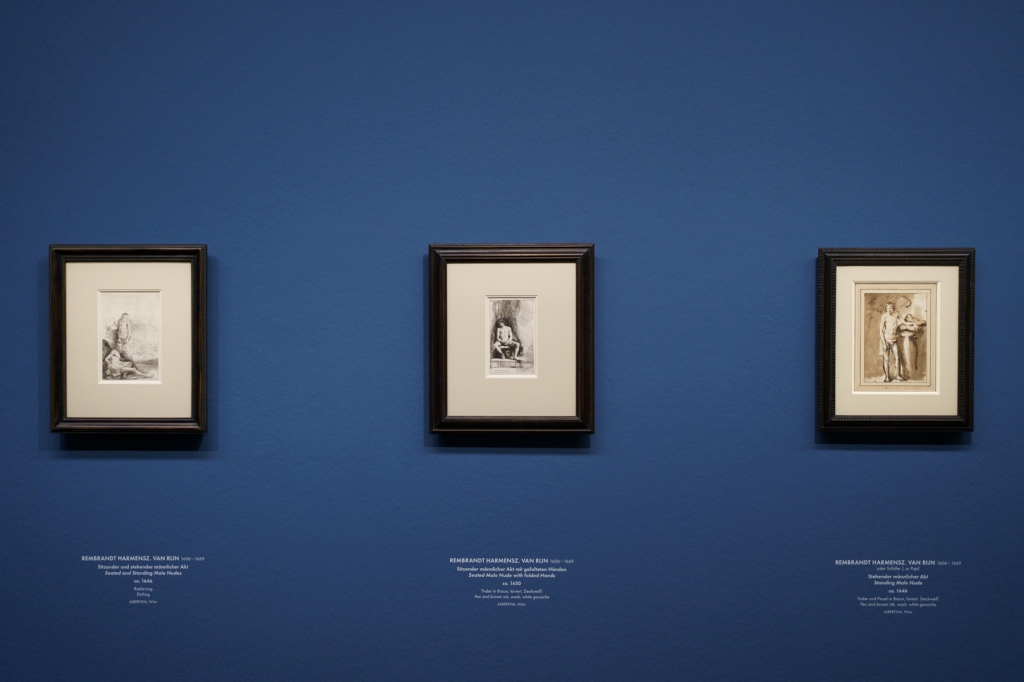

Meanwhile in the other corner, Adriaen de Vries’ Christ at the Column (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) and Paolo Farinati’s Pietà drawing forms an interesting contrast with depictions of young men by Rembrandt. As a result, the cast of Michelangelo’s Dying Slave (Louvre, Paris) in Room 2 would have had a stronger presence in this – albeit small – room, instead of feeling like an afterthought.

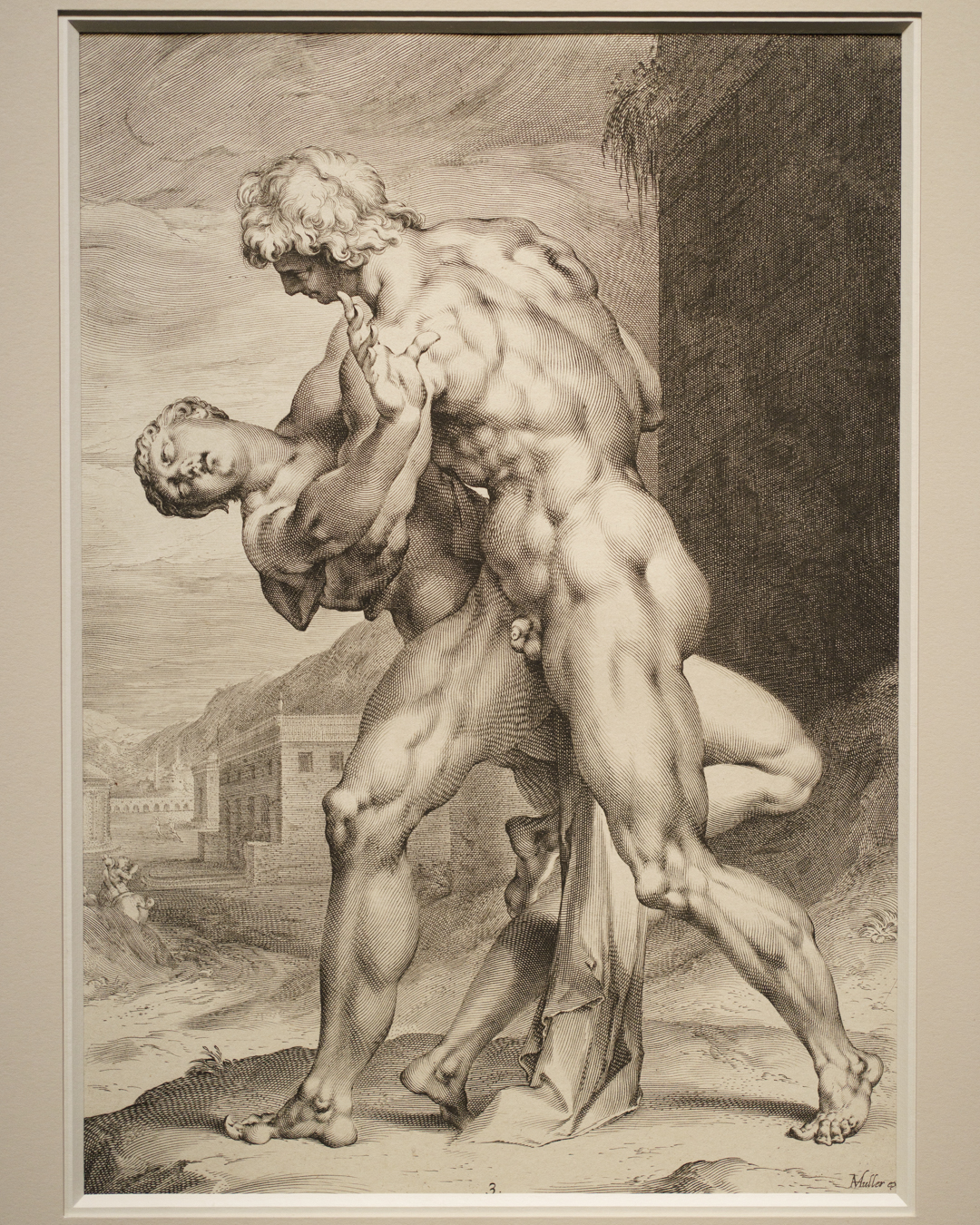

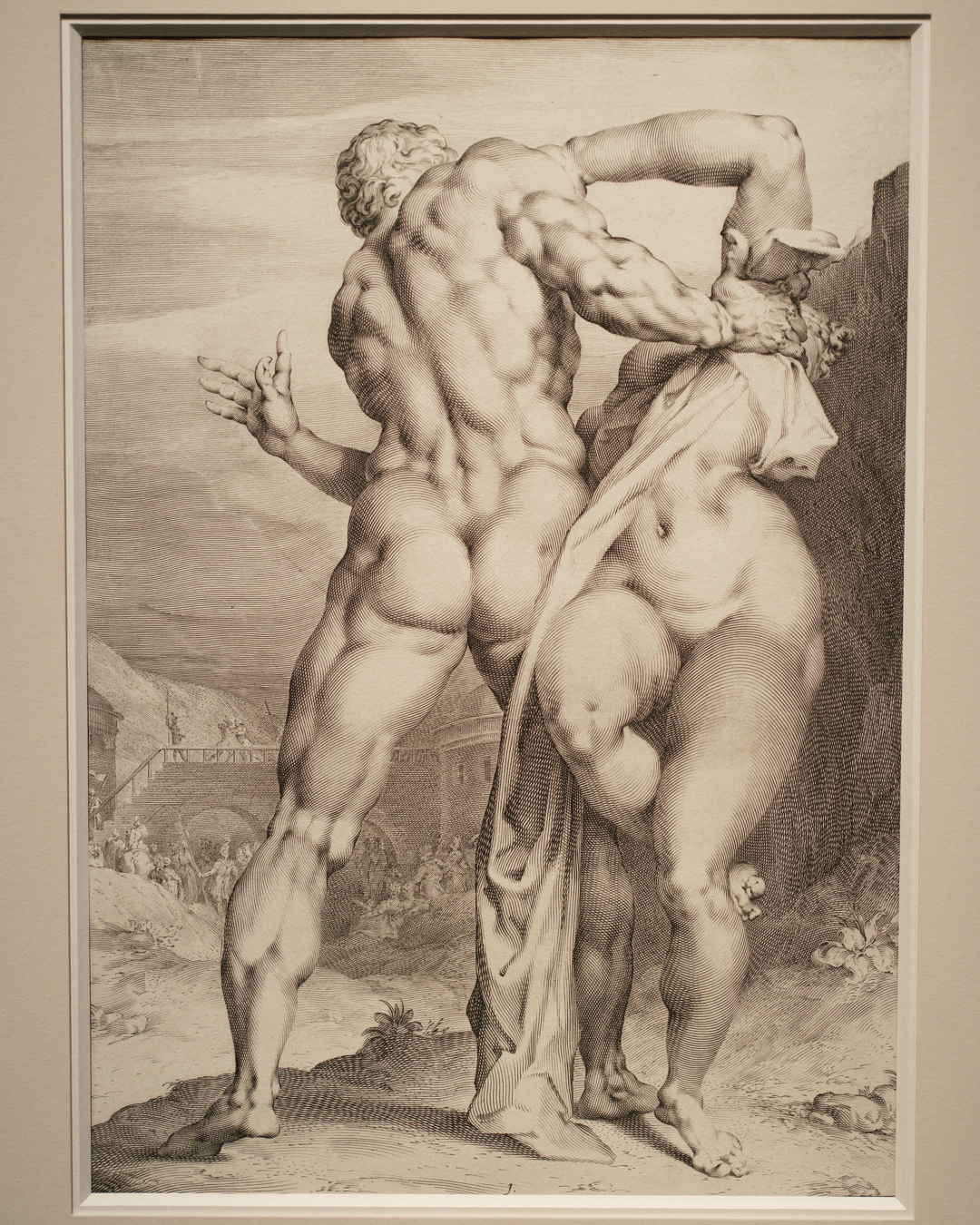

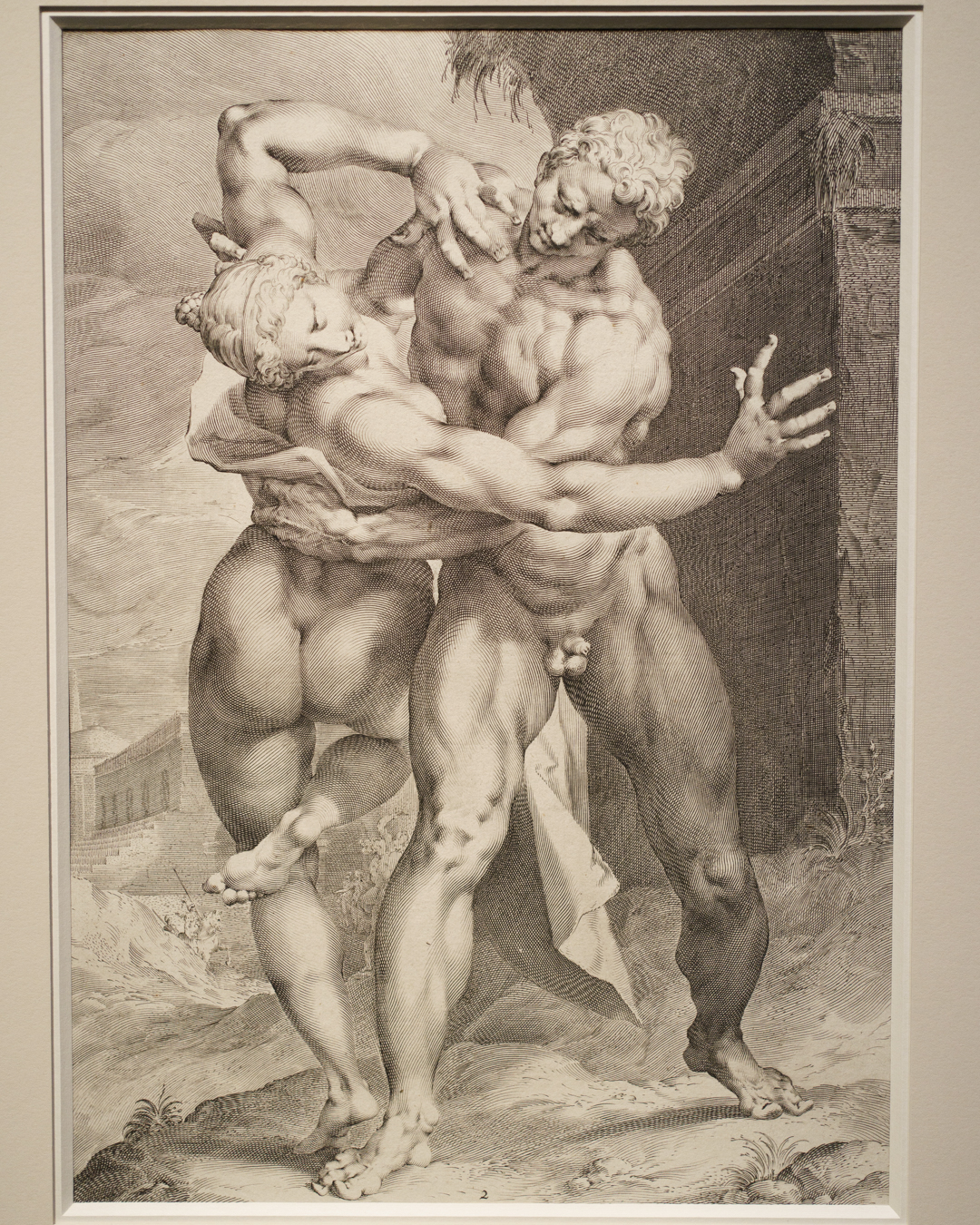

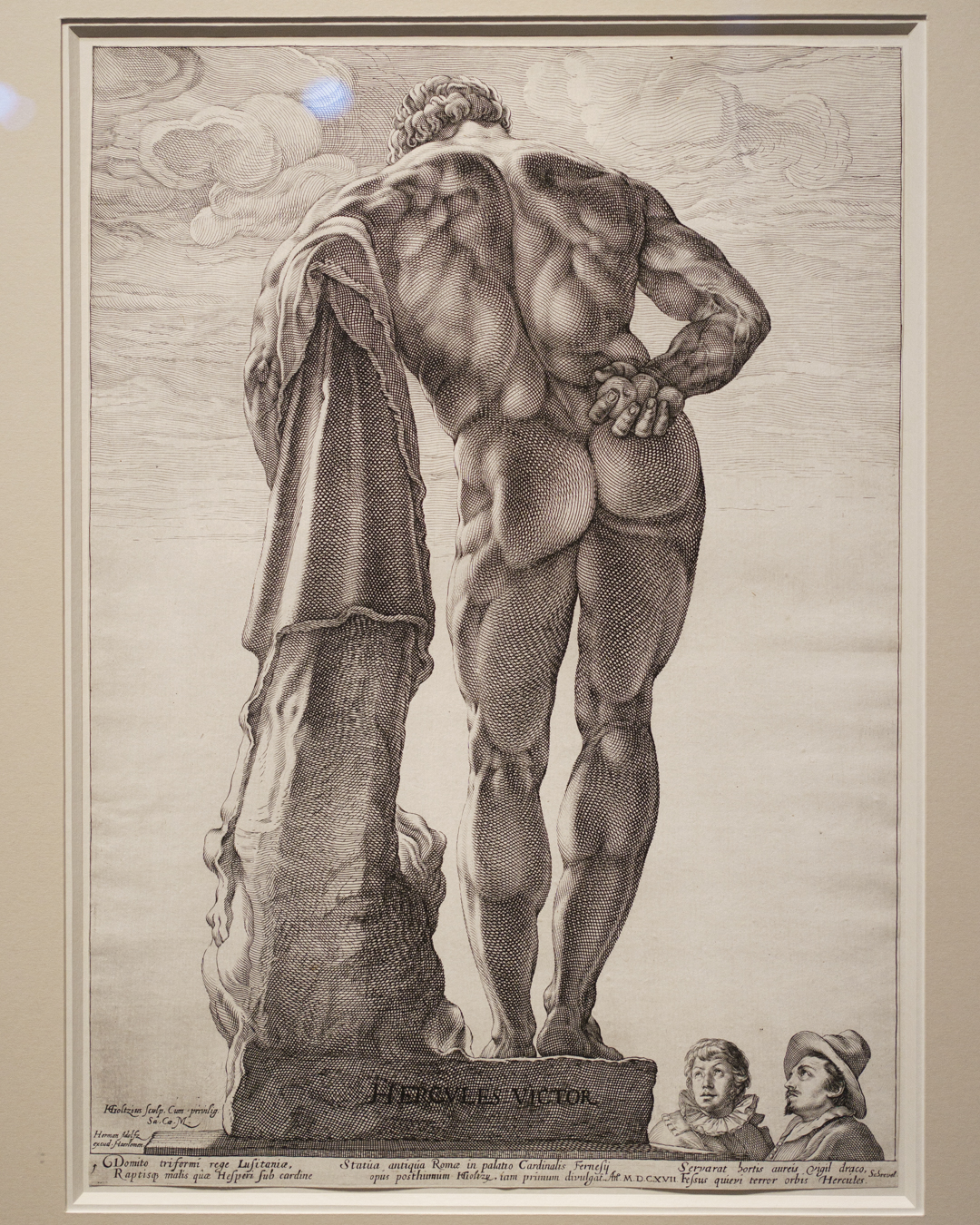

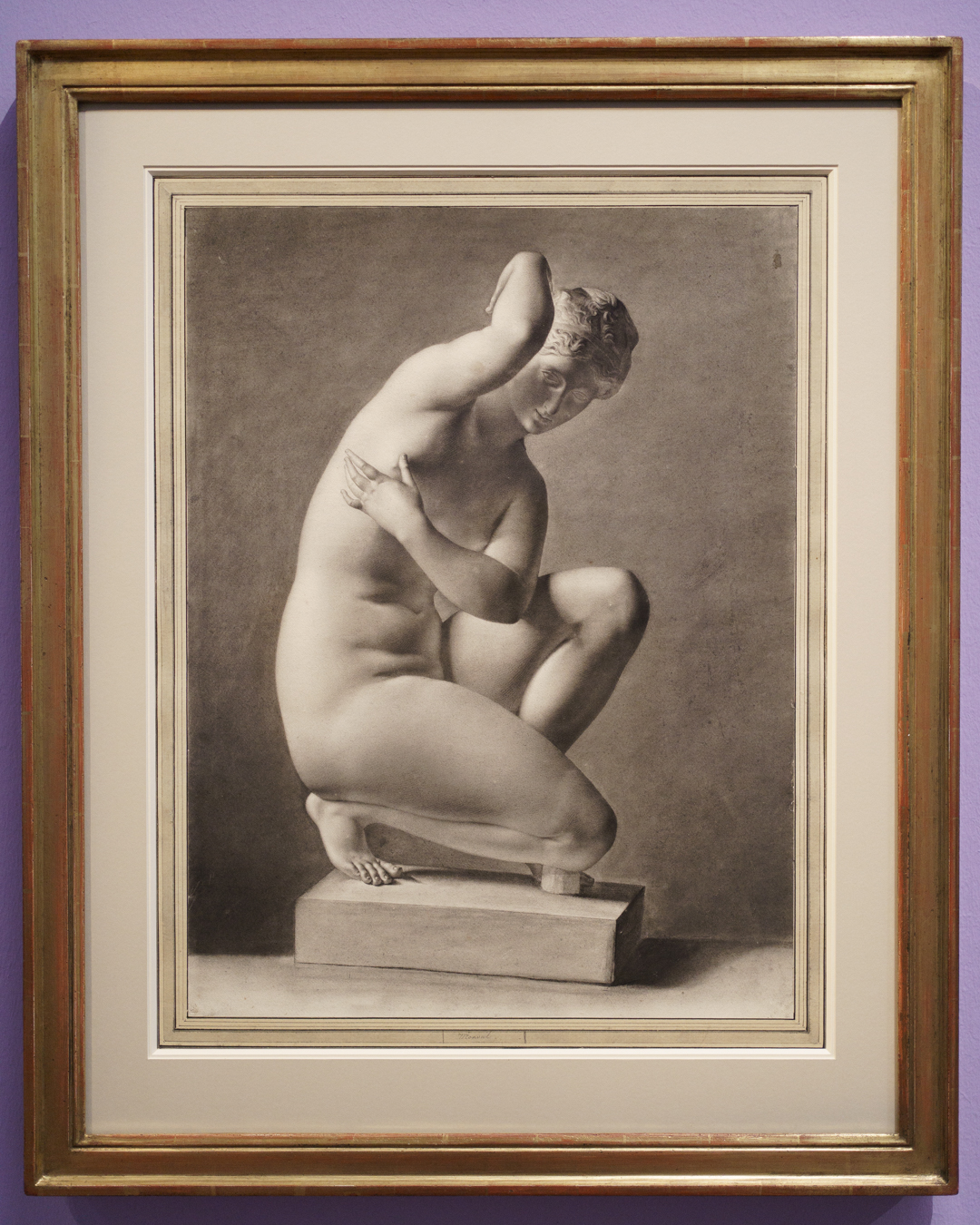

Although Room 5 included a section on appreciating sculptures ‘in the round’, the layout doesn’t actually allow for 360° viewing of the small casts of the Farnese Hercules (rediscovered in 1546), Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women, and the antique Wrestlers. Fortunately, Hendrick Goltzius’ engraved rear view of the Hercules is included. Jan Harmensz. Muller’s dual views of the Sabine Women episode are also equally worth seeing for their masterful execution in engraving. The adjacent room exploring the female body (Room 7) rectifies this by presenting two small bathing Venus sculptures in alcoves containing five mirrors, thus simulating a complete view.

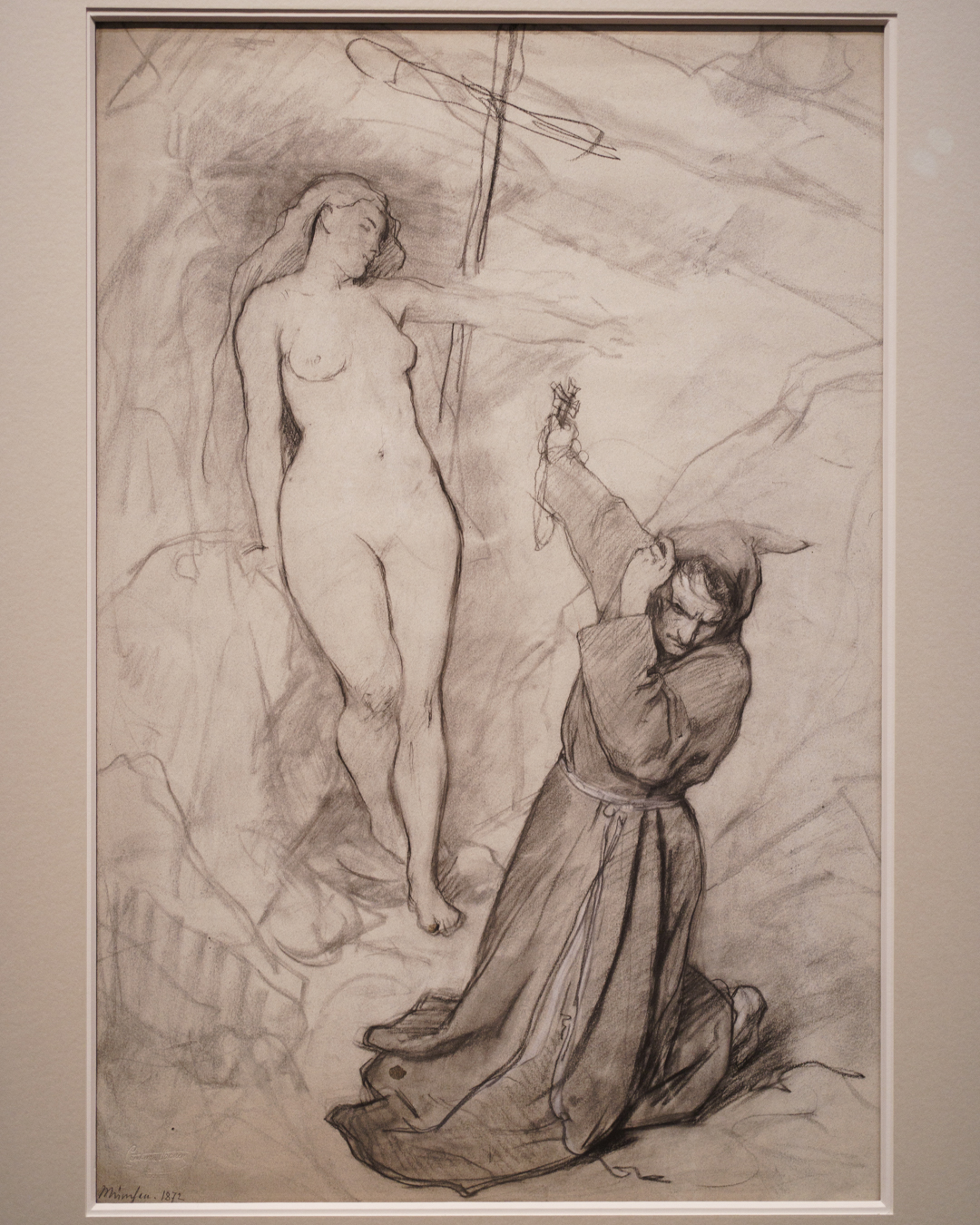

By juxtaposing depictions of real and imaginary bodies, the age-old nude vs naked debate is reawakened, in which the naturally-born mythological nude is glorified while the undressed naked body is embarrassed and obscene. This largely applies to the female body, as illustrated by Cecil van Haanen’s Temptation of St Anthony in a brilliant wall dedicated to the male fear of sexuality. Of course, some versions of the slender male body also had their negative connotations due to associations with the deity Dionysus/Bacchus, but these were fundamentally dependent on traditional receptions of women as the irrational, weaker sex. Such a complex topic would have been impossible to address in this exhibition, so its absence is understandable. This point only serves to add additional context to how such different body ideals were created in antiquity, so is largely a non-issue for post-antique representations.

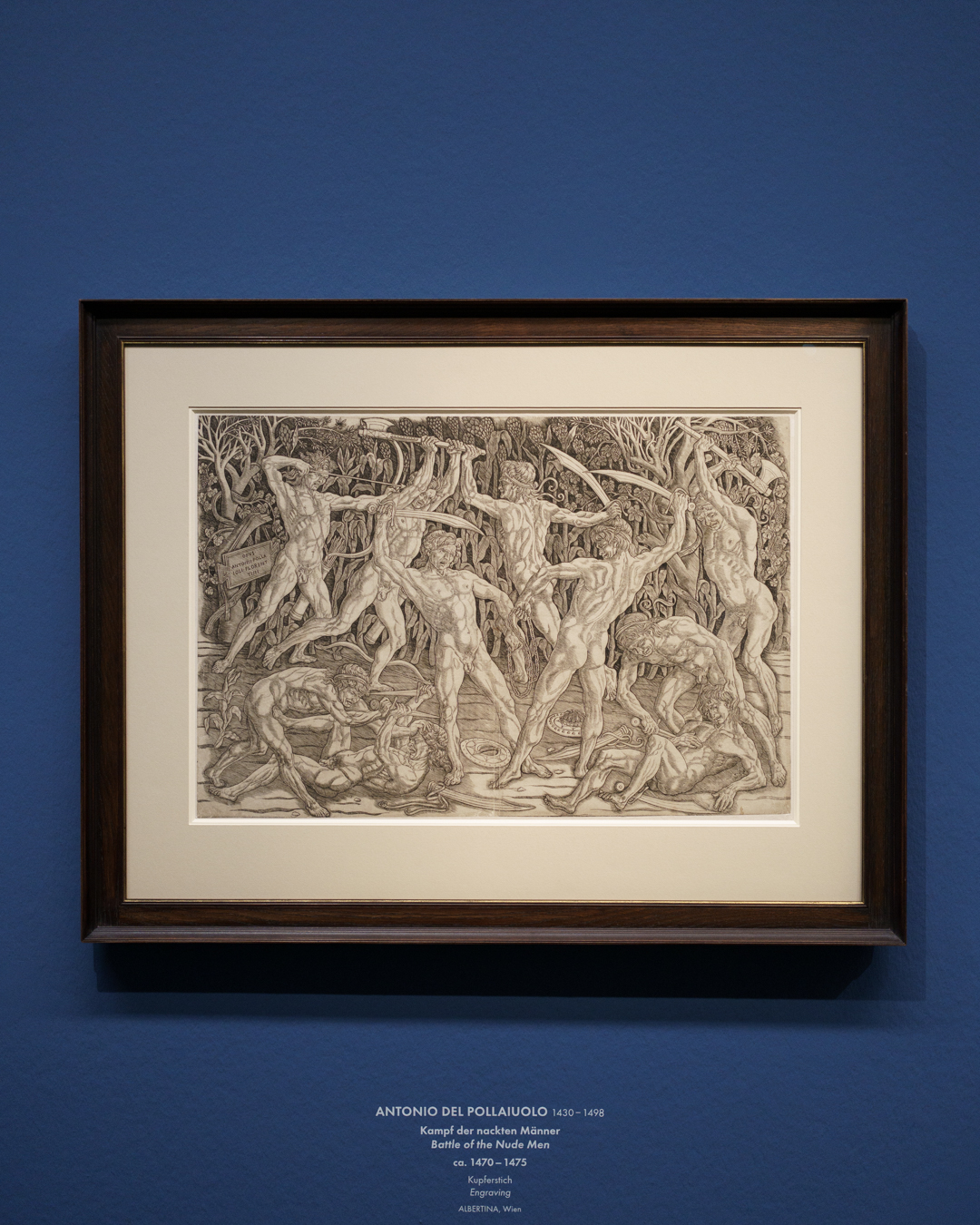

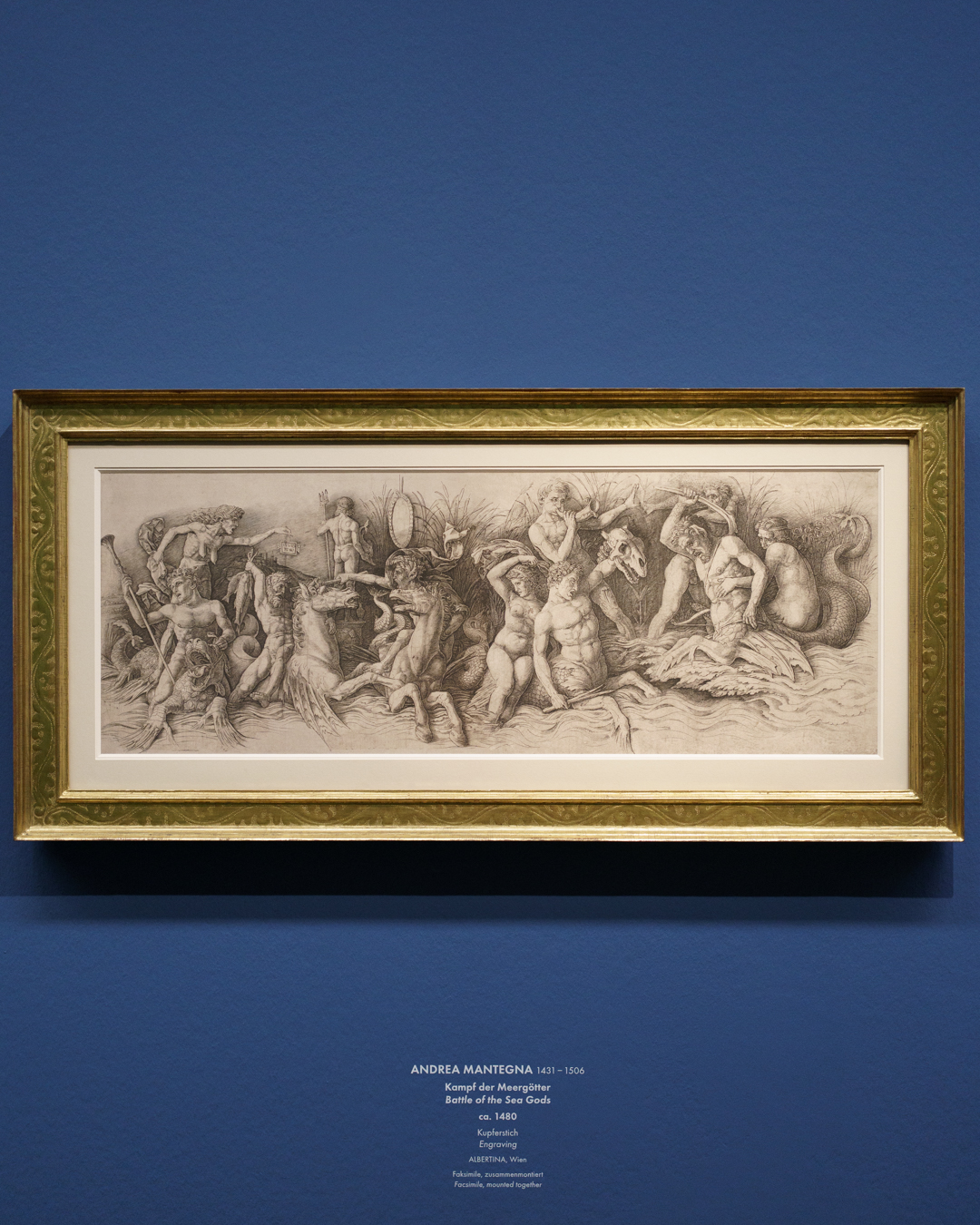

Depending on your expectations going into this show, it will either be disappointing or potentially insightful. Michelangelo enthusiasts will largely be annoyed, despite the rare opportunity to view his drawings in the flesh. Due to the transhistorical nature of the discussion, and perhaps controversially, I felt the Michelangelo drawings were not split up enough across the various rooms to convince viewers of the centrality of his influence, which absolutely existed in the curriculum of art academies for generations. Instead they were practically all lumped into the first two rooms alongside the Laocoön and Pollaiuolo prints, probably for the sake of a strict chronology.

But for the astute and observant, there was clearly potential for unexpected comparisons. Heavily underutilised was the opening room’s cast of Michelangelo’s Bacchus (Bargello), which would have filled the fragmentary exploration of the youthful, slender male nude alongside Rembrandt’s studies of young men; an additional representation of the Apollo Belvedere would have been perfect. This presents a more accurate and balanced view of the different masculine ideals being revered across time and art.

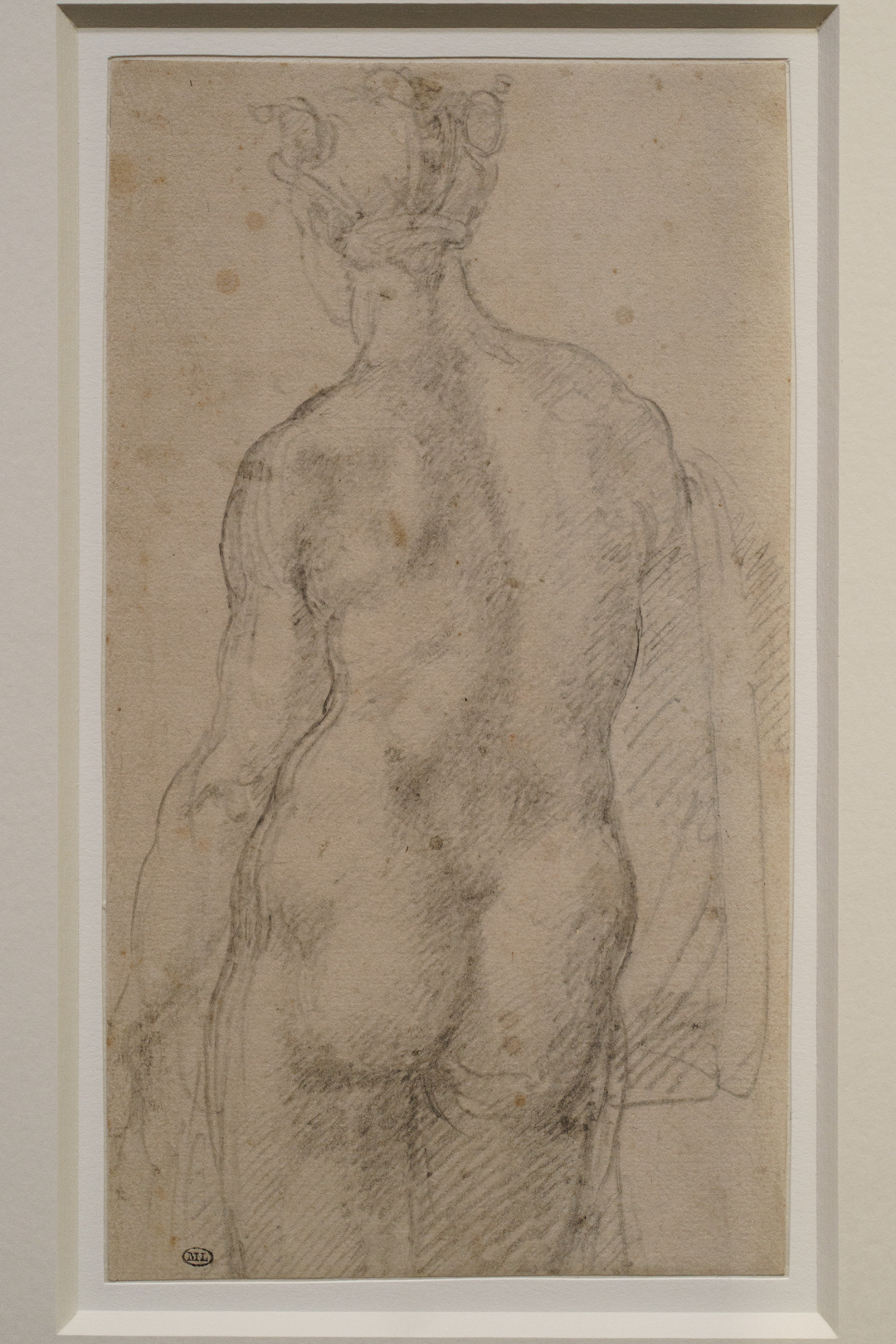

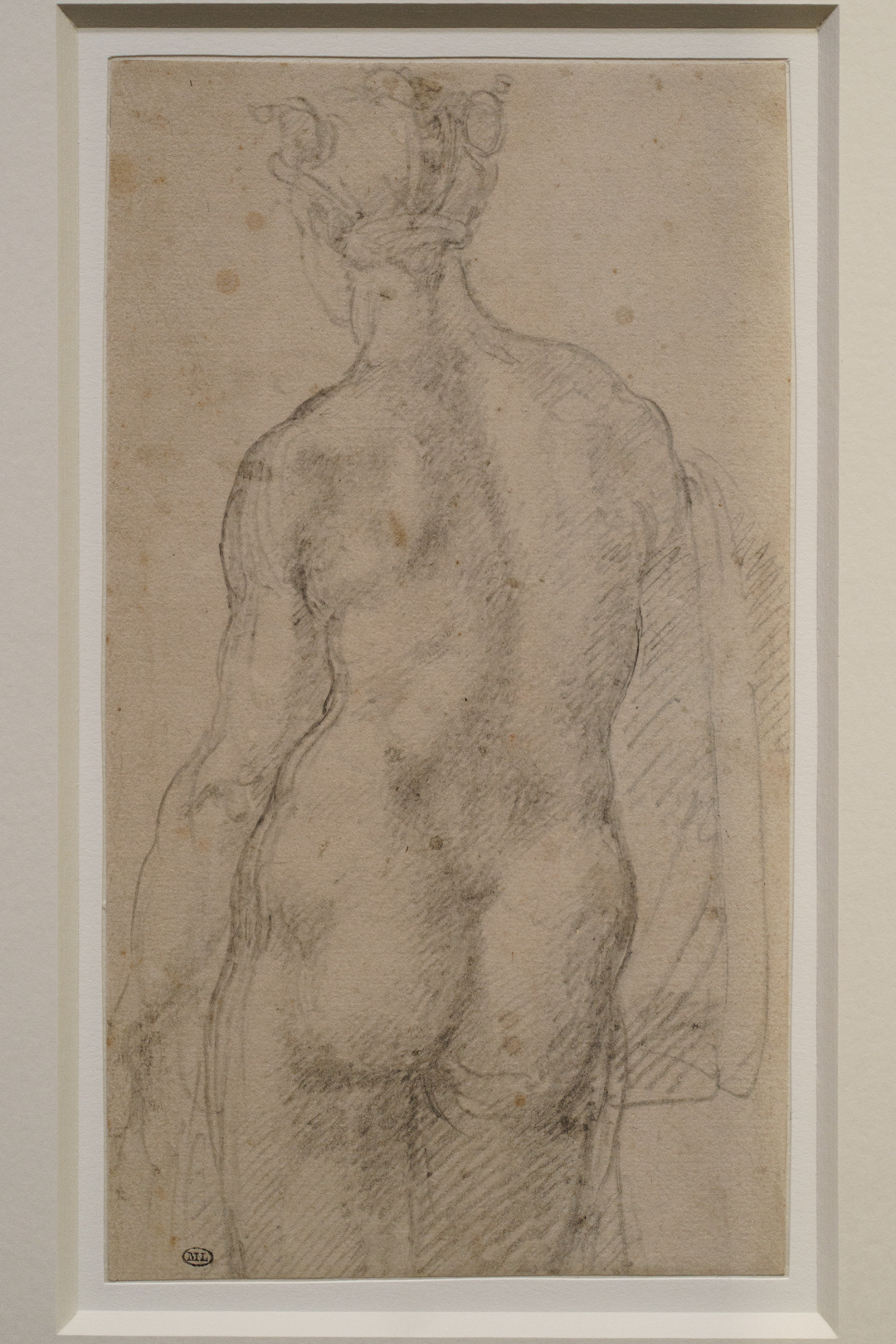

Furthermore, having Michelangelo’s studies of female nudes excluded from the relevant room – in favour of an unbroken wall of Louvre loans – sacrificed the opportunity to show visually just how exaggerated and masculine his depictions of women really were. One of those drawings, a back view of a female nude, is said to have been based on a small cast of the Capitoline Venus type that he personally owned, a link that fits well with the other Venus sculptures in Room 7.

Lovers of drawings will have plenty to ride home about, regardless. If one were to retitle this exhibition, it would probably be The Nude Across Time: From Michelangelo to Schiele. If you’re conveniently in Vienna for the holidays, I can recommend this show for its material quality and interesting comparisons. But for others, the beautifully-produced catalogue will more than suffice.

Michelangelo und die Folgen / Michelangelo and Beyond runs from 15 September 2023 to 14 January 2024 at the Albertina Museum, Vienna, https://www.albertina.at/en/

Leave a comment