The second half of my weekend involved an early morning to visit the Paris Catacombs. The queue circled around the park with a wait of over an hour – who knows how many people were in the line. I walked there with most of the group but soon decided to give up and find my own adventure.

Walking to the Paris Catacombs.

A little known secret in the southern part of Paris is the Manufacture des Gobelins – the Gobelins Manufactory. This was a royal tapestry factory that produced illustrious tapestries for the court of Louis XIV in the 17th century and his successors. Nowadays it produces limited tapestries for French governmental institutions and is owned by the French Ministry of Culture.

The Gobelins family were dyers who established themselves in Faubourg Saint-Marcel on the banks of the Bièvre, a former (now underground) river that ran into the Seine on the Left Bank. The conversion of their business into a tapestry factory was due to Henry IV of France, who rented space from the Gobelins for his two Flemish weavers Marc de Comans and François de la Planche in 1602. The rented factory space is now the current site of the Gobelins Manufactory. By 1633, Marc’s son Charles de Comans had become head of the manufactory, after taking over his father’s workshop in 1629 with François’ son Raphaël de la Planche. At around 1650, their partnership ended and the workshops were split in two.

In 1662, on behalf of the Crown, Jean-Baptiste Colbert – Louis XIV’s Minister of Finance – bought the manufactory and turned it into a general upholstery factory, making furniture as well as tapestries. It gained the official title of Manufacture Royale des Meubles de la Couronne (‘Royal Factory of Furniture to the Crown’). Charles Le Brun became the director and chief designer from 1663 to 1690, but due to Louis XIV’s financial problems the establishment closed in 1694. Fortunately, the closure was short-lived, reopening in 1697 for the sole production of tapestries, rivalling those made by weavers at Beauvais, also under Colbert’s general direction. Work was suspended once again during the French Revolution but it was revived during the Bourbon Restoration, with carpets being added to its production in 1826.

It is apparently possible to visit the factory by appointment only, but I was most interested in visiting the Galerie des Gobelins, a museum open only to the public during temporary exhibitions. But first I needed to get there. Since the catacombs were located in Place Denfert-Rochereau, it was timely for me to walk along Boulevard Saint-Jacques.

Two rows of trees line the pavement. A young man turns into a corner holding a bouquet of flowers, probably on the way to the Centre Hospitalier Sainte-Anne. A four-or-five-year-old little boy rides a small bicycle with training wheels, his middle-aged parents strolling behind him. Finally, two elderly men converse on the green benches that are scattered along this street, with a perfect mix of light and shade. It wasn’t very long until I reached the Marché Auguste Blanqui, a local village-like market selling a vast variety of food items – all sorts of cheeses, cooked meats (even fresh roast chicken), frozen meats, fruits and vegetables – and household items and clothing. Open every Tuesday, Friday and Sunday, it spans most of the length of the Boulevard Auguste-Blanqui, between Rue Barrault and Place d’Italie – just to clarify, at some point along Boulevard Saint-Jacques it becomes Boulevard Auguste-Blanqui, roughly where the Rue de la Santé is located.

Seafood.

Roast chicken.

Vegetables.

It wasn’t particularly long before I became distracted by an opening, Rue Eugène Atget – after the French photographer and well-known flâneur – which appeared to lead into a paradise of greenery. With time to spare and no reason to hurry, I went up the steps through the opening to see what I could find. At the top of the stairs was a local playground, the Jardin Brassaï, named after the Hungarian photographer who photographed many artists of the time, including Picasso, Matisse and Giacometti.

Jardin Brassaï.

Continuing along this path, I found a wonderful little café on the corner of Rue Jonas and Rue des cinq Diamants. Called Au Passage des Artistes (‘The Artist’s Way’) it was in a wonderfully quiet area of the Butte-aux-Cailles neighbourhood in the 13th arrondisement. A middle-aged man with messy grey hair was already sitting at one of the tables outside, drawing geometric shapes in his sketchbook with an espresso by his side. Often he would gaze upon the deserted residential street, add a few marks to his drawings, and every now and then he would jot down some thoughts in French. I ordered a café crème inside and sat at a table next to this contemplative figure.

Pen, notebook, and a café crème at Au Passage des Artistes.

He appeared somewhat distinguished with a calm air surrounding him. I felt I could relate to him, at least during this brief period when I was stress-free from university assignments and the only worry I had was for my own safety in the City of Light. My mind was cleared of things I needed to do, of deadlines, of my future dissertation (Oops!) and of my future MA applications (Oops again!).

I was content.

A favourite past-time for Parisians and introverts like myself is people-watching. In the evenings, the chairs outside restaurants and cafés are intentionally positioned to face the street. People-watching is an everyday activity. It encourages inspiration and creativity – such was the case for the man beside me – an ever-changing atmosphere where topics for discussion can be obtained, and most importantly of all, a space for silence, quiet contemplation and personal reflection. Also, by looking out into the street you have an excuse to stop talking to the person beside you without it being awkward.

The introspective man drawing geometric shapes.

I saw grandparents taking their grandchildren to the park and teenagers on skateboards. I saw a grandmother with her daughter walking side-by-side, each pushing a pram holding a pair of tiny grandchildren, probably conversing about motherhood from one generation to the next. I was able to appreciate the beauty of the graffiti works of Miss.Tic which adorned the front of Chez Gladines on the opposite side of the road. Possibly for the first time, I was even able to hear the birds singing in the background.

Born in Montmartre, Miss.Tic is an urban artist and poet based in La Butte-aux-Cailles. After secondary school, she spent some time in California, USA, before returning to Paris. While not quite as elusive as Banksy or as radical as the Guerrilla Girls, Miss.Tic’s street art is a social commentary on the role played by women in society, of a life lived without fear. Many of her artworks feature seductive women accompanied by short phrases, such as “Les actes gratuits ont ils un prix?” (“Free acts have a price?”) and “Idéaliste devenez ideal” (“Idealistic becomes ideal”). Other pieces use male figures to question male identity and dominance in society, such as “Le masculin l’emporte mais ou?” (“The male wins but where?”).

Miss.Tic’s street art adorns the front of Chez Gladines.

Her “art for everyone” dominates the streets of the neighbourhood to the point of becoming an icon of La Butte-aux-Cailles – Paris-Mythique, a local souvenir shop, sells items that are specific to La Butte-aux-Cailles, including official sticker reproductions of Miss.Tic’s artworks. However, as with any street artist, she was arrested and trialled for degradation of public property in 1997 and fined 4500€. Nowadays, her works are made with permission from store owners. New York City-based writer Patricia Duffy wrote a wonderful piece on Miss.Tic in BigCityLit, accessible here.

I stayed at Au Passage des Artistes for nearly an hour, knowing that I could spend the entire day there, but it soon dawned on me that I had less than a week left to experience the city, therefore, time was of the essence. I walked back the way I came, passing an elderly woman walking down the steps with her grandson sitting inside her shopping cart, clearly having no idea what was going on. I felt like asking if she wanted help, after seeing her slowly descend the steps one by one with the basket hitting the ground each time, but then I remembered I couldn’t speak the language.

A toddler in a wheeled shopping cart!

I browsed the stalls a little more, even opting for three juicy nectarines for €0.50. Eventually I reached the last of them and arrived in Place d’Italie. This consisted of a large roundabout with a very peaceful public green-space in the centre. The square’s name derives from its proximity to the Avenue d’Italie, a traditional departure point on to the Route nationale 7 which links Paris and the border of Italy.

Finding the imposing façade designed by the architect Jean-Camille Formigé along the Avenue des Gobelins wasn’t difficult, especially because it was adorned with bright pink banners promoting its two current exhibitions: Les Gobelins au siècle des Lumières (‘The Gobelins in the Enlightenment’) and Carte Blanche à Pierre et Gilles. Prospective visitors should know that the Galerie des Gobelins is only open during temporary exhibitions – fortunately, this tends to be most of the year. On select days there are also guided tours to visit the factories themselves.

Galerie des Gobelins.

The main entrance was located at the side of the building, not the main façade as one would expect. Past the spinning doors, I found myself in the reception area where I had to buy my ticket at the tiny bookshop to my right, consisting of a single countertop and a few shelves on the wall behind. The exhibition began on the top floor.

It was clear from the lack of footsteps and emptiness of the first room that this was not a frequented museum – then again, it was a Sunday. I must have spent a good two hours in there and I counted less than ten visitors. I indulged in the silence as best I could.

Charles-Antoine Coypel, The Sacrifice of Iphigenia, c. 1730.

Les Gobelins au siècle des Lumières presents a selection of tapestries made for the royal court during the 18th century alongside painted models and furnishings. Personal highlights included a representation of the Miraculous Draught – after one of four New Testament paintings by Jean Jouvenet – and the Sacrifice of Iphigenia (c. 1730) by Charles-Antoine Coypel which took pride of place over the grand staircase, flanked by two other mythological tapestries in Jean-François de Troy’s oeuvre which represent his Histoire d’Esther (1737-80) and Histoire de Jason (1743-46) tapestry series. Coypel is best known for his Don Quixote series (1714-94) exhibited downstairs, illustrating Cervantes’ novel of the same name.

Pretty furniture!

A small display of lithographs show the weaving process step-by-step. In the same section we are presented with a selection of chairs and furnishings made under the general direction of Jean-Baptiste Colbert. It wasn’t surprising to see how the tapestry-making process could be used for furnishings once I saw the depth of the tapestries on display, approximating a very thin 5-10mm each. However, I was even more surprised by the incorporation of this process into formal portraits. From a distance, these tapestry portraits appear like ordinary painted court portraits – trained-eye or not – but once you move in closer all the fine threads reveal themselves like a Van Gogh or Pissarro painting, even a Titian if you want to be mind-blown.

This is NOT a painting.

In the lower gallery there is more of a focus on individual artists, mostly the ornamentalist Maurice Jacques who began working in the manufactory in 1756 as a painter and designer. His trademark was his alentours – wide, elaborate borders decorated with flowers, birds, animals and symbolic items – which would surround a central painted subject or scene.

Maurice Jacques’ ‘alentours’ on the left.

One of the other principal designers for the Gobelins Manufactory (and a favourite artist of mine) was François Boucher who headed the manufactory between 1755 and 1770. Boucher’s work often draws from classical themes, such as his Amours des Dieux series. However, I was particularly drawn to something cuter, a set of painted models depicting little boys and girls dressed as small farmers. The five paintings exhibited were part of a set of 20 made for Madame de Pompadour around 1751-52. They are absolutely adorable! – I really liked the little fisherman and the little bird-tamer.

Look at how cute they are!

I briefly ventured into the Pierre et Gilles installation in the Salon Carré which consisted of a photographic portrait of model Zahia Dehar atop a fireplace as its centrepiece. On either side were pieces of furniture intruded on by large rats. The installation is in dialogue with the tapestry exhibition. Zahia Dehar is shown here in the guise of Marie-Antoinette and the furnishings are all reminiscent of the era of Louis XVI. Pierre et Gilles, consisting of romantic partners Pierre Commoy and Gilles Blanchard, are known for embracing art historical themes with contemporary culture within their hand-painted photographs, including gay culture. They attracted controversy in 2012 in Vienna when they advertised their Nackte Männer (‘Naked Men’) exhibition using Vive la France (2006) on large street posters, a piece depicting three naked footballers with visible genitalia.

Pierre et Gilles installation.

The lower gallery also held a display of Olivier Mourgue’s Bloc Mobile pour Chaque Fonction (‘Movable Block for Each Function’), isolated purpose-built cubicles which can be rearranged in various layouts to create a functioning house that can be constantly altered. Amongst others, there was a movable kitchen, a couple of bedrooms which contained as much space as a large tent, and a block with partitions that placed the toilet, sink and bath/shower in separate cubicles. Mourgue, a French industrial designer, is better known for his contribution to the film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) where his Djinn chairs were made famous. The presence of this display did, however, disturb and interrupt the viewing of works in the main exhibition.

Plan view for Olivier Mourgue’s Bloc Mobile pour Chaque Fonction.

My next destination was a little more appropriate for the day. I was determined to go to church on a Sunday and the Panthéon was perfect for the occasion. After all, my own church was miles away across the English Channel! It was time for another walk…and a lot of graffiti.

A lot of very nice street art!

I went along the rest of the Avenue des Gobelins, eventually reaching the small fountain in front of the Starbucks that myself and two of the others had passed on Thursday evening. Eager for a drink, I popped into a nearby shop for some juice before passing some waste collectors at work while walking towards Rue Mouffetard. Halfway up, I stopped for some lunch at a restaurant and bar, perfectly named Le Mouffetard. In an attempt to say “Une table pour un” it inevitably led to failure and the bartendress to use single-word statements. Manger?

Le Mouffetard.

I picked a table in a corner between a wooden screen and a wall with two framed pen drawings – signed “R. Levy” – and a photograph hanging from its surface. The black-and-white photograph was of a singer in mid-performance, accompanied by a female accordionist while a bartender to the left of the image serves wine to standing customers. After observing the menu and having a carafe d’eau brought to me, I indulged in my relaxed environment with a bit of travel reading. Behind me I could hear the sound of French locals dining and conversing and clinking their glasses. Close to the entrance, on the other wall, I could hear two women talking in English with glasses of rosé – they might have been mother and daughter.

Interior of Le Mouffetard.

The photograph and drawings next to me.

At around this time, roughly 1-2pm, my previous group had just exited the catacombs and began making their way to the Jardin du Luxembourg for a picnic lunch.

Soon I was presented with a plate of grilled salmon, rice, a small pot of béarnaise sauce and an espresso – the latter was probably more appropriate after I’ve eaten. I was thoroughly impressed with my dish. The salmon was extremely well done, flittering between melting in one’s mouth and having to chew with minimum effort. The skin was gently crisped and the overall texture was just perfect. I think I also became a little addicted to the béarnaise sauce.

My lovely lunch!

In the background a mixture of soul and jazz music resonated throughout the establishment and it encouraged me to read a bit more. A middle-aged couple attended to the table beside me in the meantime. Eventually I resisted from getting too comfortable, paid the bill and continued on my journey to church. I passed a rather quaint novelty store called Nalola… and browsed for a little bit. Aside from a few ordinary items and adult-themed novelties typical of a store like Menkind, most of the merchandise were actually incredibly unique, sometimes French-themed. Sadly, they were a little pricey.

Nalola…

It was a really nice sunny day so queues formed at most glaciers such as Gelati d’Alberti, known for their flower-shaped creations. A little longer and I arrived at the Panthéon, whose entrance had a wonderful view of the Eiffel Tower poking out of the trees.

View from the Panthéon.

The present site of the Panthéon was originally the old crypt of a Christian basilica built in 507 AD by King Clovis I, then known as the Abbey of St. Geneviève. The saint herself was buried there in 512 AD, close to the remains of Clovis and his wife Clotilde. Her shrine, however, resides inside the church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, where the little that remains of her relics are contained, following their public burning in 1793 at the Place de Grève.

By 1755 the architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot was in charge of redesigning the new basilica, organised by King Louis XV in 1744. In an attempt to outdo St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome – while modelling its façade on Rome’s own Pantheon – it was eventually completed in 1790 by Soufflot’s associate Jean-Baptiste Rondelet. The former’s tomb was soon added to the crypt in 1829.

In 1791, during the early stages of the French Revolution, it was changed from a church to a mausoleum to house the remains of great Frenchmen – effectively becoming a national monument – ordered by the National Constituent Assembly after the death of their president at the time, Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau. This change recurred twice and today it is still remains as a mausoleum.

Interior of the Panthéon.

As I entered the national monument I noticed the cycle of paintings lining its every wall, dedicated to the history of Saint Geneviève, the beginnings of Christianity and that of the monarchy in France. I was finally able to witness first-hand some of the work of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, one of the co-founders of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. It should be noted that these paintings are not frescoes, merely canvas marouflé (canvas stuck on to a different surface).

Paul-Joseph Blanc, The Vow of Clovis at the Battle of Tolbiac, c. 1881.

At the base of the pillars below the dome was a group of four sculptures commemorating events such as the French Revolution and the Bourbon Restoration. Corinthian columns emphasise the Greek-cross outline of the interior, and where the high altar should have been was François-Léon Sicard’s sculpture The National Convention (1921-24), depicting Marianne – the national emblem of the French Republic – surrounded by parliamentary members and soldiers from the second year of the First French Republic. On the wall behind this was a battle scene, and directly above was a fresco reminiscent of Byzantine art.

François-Léon Sicard, The National Convention, 1921-24.

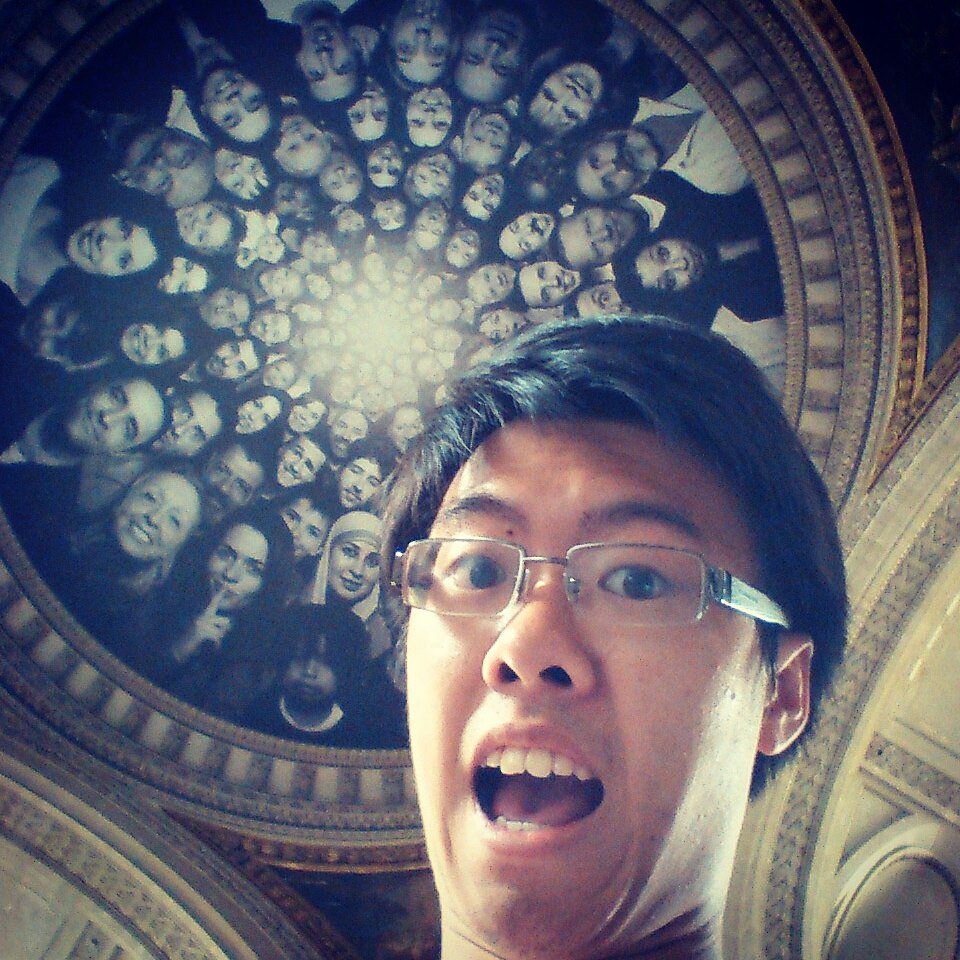

On the dome, Antoine Gros’ Apotheosis of Saint Geneviève (1811-24) was now covered by contemporary artist and photograffeur JR’s installation of black-and-white portraits. Commissioned by the Centre des Monuments Nationaux, Au Panthéon is a participatory work inspired by his INSIDE OUT project, “a global art project transforming messages of personal identity into works of art”. Portraits were self-submitted to the project website and then printed out and collaged to create the immersive installation.

I don’t think he knows what this is all about…

And immersive it certainly was…

In my defence, everyone else had the same idea!

I then visited the crypt, where the most popular tomb was that of the French writer, historian and philosopher François-Marie Arouet, better known by his pseudonym Voltaire adopted in 1718. The pseudonym is an anagram of “AROVET LI”, the Latin spelling of his surname in combination with the initial letters of “le jeune”, meaning “the young”. Voltaire also appears seated on the left of the Panthéon pediment with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a Gevevan philosopher, writer and composer whose tomb lies directly opposite that of the former.

The tomb of Voltaire.

The pediment of the Panthéon.

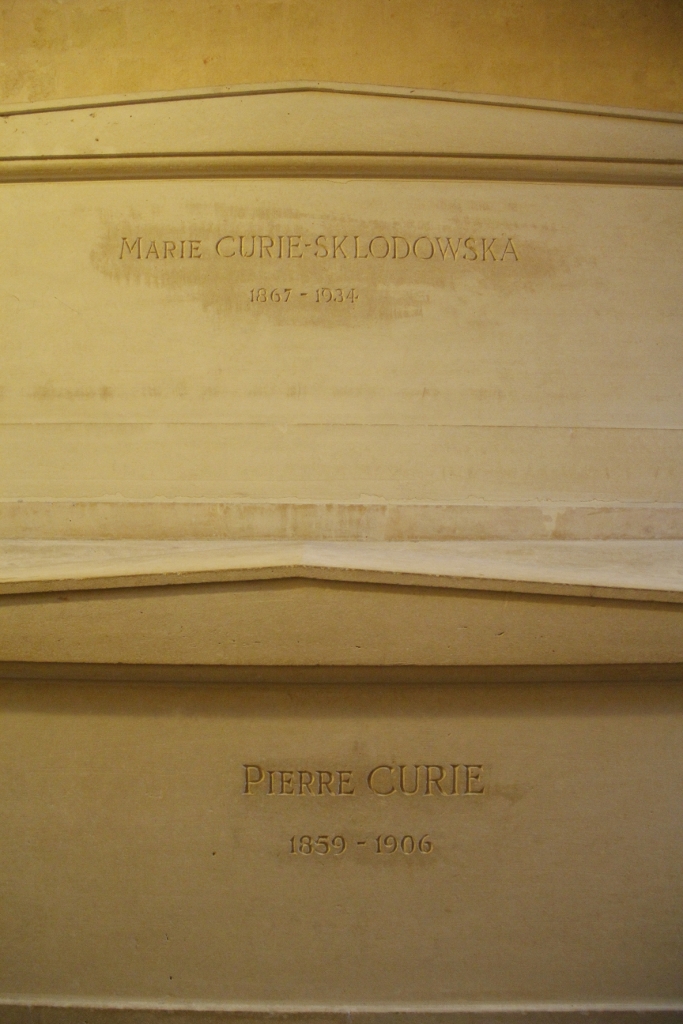

As I ventured further, I discovered the tombs of many other notable figures such as Victor Hugo, Émile Zola and Louis Braille. However, I was most excited by the eye candy that was the tomb of the first woman to be interred at the Panthéon on her own merits, Marie Curie-Sklodowska, together with her husband Pierre Curie in 1995. However, Marie Curie was not the only woman interred at the Panthéon; the first woman ever interred there was Sophie Berthelot, the wife of the French chemist and politician Marcellin Berthelot – in thermochemistry he is known for suggesting the Thomsen-Berthelot principle, the hypothesis that all chemical changes are accompanied by the production of heat, later disproved in 1882 by the German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz.

Marie and Pierre Curie’s tombs.

After a relatively long day of walking, whether inside a gallery of tapestries, a giant church, or the many boulevards that dominate the city of Paris, I was inclined to rest my feet back at the hostel. Serendipitously, this did not go as expected.

I ended up heading into the Jardin du Luxembourg where I was greeted with a plentiful crowd listening to a live piano performance of the opuses of Frédéric Chopin. This was part of the 50th edition of the Chopin au Jardin du Luxembourg music festival (15th June – 13th July 2014) which consists of five concerts on five consecutive Sundays. The pianist on the day was Andrzej Jagodzinski from Poland who specialises in jazz music, having represented Polish jazz for over 16 years, even performing with Ewa Bem, “Poland’s first lady in jazz”, since 1981.

Andrzej Jagodzinski playing Chopin.

Now that I had been distracted by Chopin’s elegant and light compositions, I couldn’t resist taking a seat to read while overhearing the grace notes, delayed cadences and contrasting rhythms with a touch of jazz added to them. The sunlight, light breeze and warm weather were perfect too.

I was not joking about the crowds.

The performance eventually had to come to an end – sad, I know – so I made my way back to the hostel, resting a moment in my room before joining some of the others on the balcony. Not too much longer and we were hunting for dinner, finally settling for a small traditional bistro called Le Vieux Bistrot on Rue Mouffetard – I think this became my favourite street ever since I was introduced to it.

Le Vieux Bistrot.

We all opted for the €12 menu, consisting of a starter, main course and dessert. They also had a €16 menu with a slightly larger selection of items. I decided to French-out, choosing a plate of escargot, boeuf bourguignon, and crème brûlée for my three courses. Naturally, I also went for the house white wine – I really should have gone for red to accompany the beef. Either way, the restaurant did not disappoint, especially for the price we were paying. I’ll admit I anticipated a little more in terms of portion size for the boeuf bourguignon, but we were all quite satisfied by the end of the meal and the beef was wonderfully tender.

Escargot; boeuf bourguignon; crème brûlée.

On the way back, we bumped into a couple of new-found friends from the hostel outside a pub called Le Requin Chagrin. We had a quick chat with them before being disrupted by a display of quad-bikers and ordinary bikers performing wheelies, circling Place de la Contrescarpe before heading down the way we came. Fortunately, I wasn’t the only one baffled by this unexpected occurrence, as I made eye contact with a chuckling American couple a few tables away. By this time, everyone else from the group had left early, leaving myself, the foodie, and our only drama student to socialise.

The stunt bikers!

The couple were living in Dallas, Texas, and they were in Paris as part of their honeymoon, the itinerary of which began in London for three to four days, through to Amsterdam, then Paris, later continuing on to Cannes. Venice was on their bucket list. One was from Philadelphia, the other from a part of Texas, and both were working in advertising. While the husband majored in the same field, his wife majored in English Literature. As a result, she was fascinated by English history and enjoyed the sights in London, visiting Westminster, Big Ben and Hampton Court Palace, to name a few. I was also told that her husband had a thing for aliens and conspiracy theories – something I’m guilty of having an interest in – and would pour many hours on the History Channel. They were a very lovely couple and we talked about the beauty of live music in a restaurant, and apparently there is a very good karaoke place in one of the pubs Ernest Hemingway attended in his time. X-Files was also on the list, as well as sunny Dallas weather compared to moody, gloomy England, and that New York had its hardest snowfall this February when I went there.

Saint-Étienne-du-Mont.

Our conversation stopped when my hostel mates decided to head to another pub. We headed north, ending up at a traditional Irish pub The Bombardier next to the Panthéon and Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. There was a World Cup game that evening – USA versus Portugal – so we had a good cheer. I eventually left early, finishing my Pepsi and wary of the hostel’s curfew, for fear of being locked out.

Watching the game inside The Bombardier.

It was a truly exhausting day, full of sensory insights and memorable encounters. For once, I felt relaxed, care-free, and without fear. I felt as if I had truly experienced life to the fullest – whether I did or not is entirely subjective – and I felt like I was living in the present. The future didn’t worry me, the past didn’t come to haunt me. I was focused on the there-and-now, on the precise happenings of every event I encountered that day, and for an entire day I was relieved from a need to anticipate my (and others’) each and every move.

And then I was reminded that I had only a week left in this beautiful city…

Leave a comment