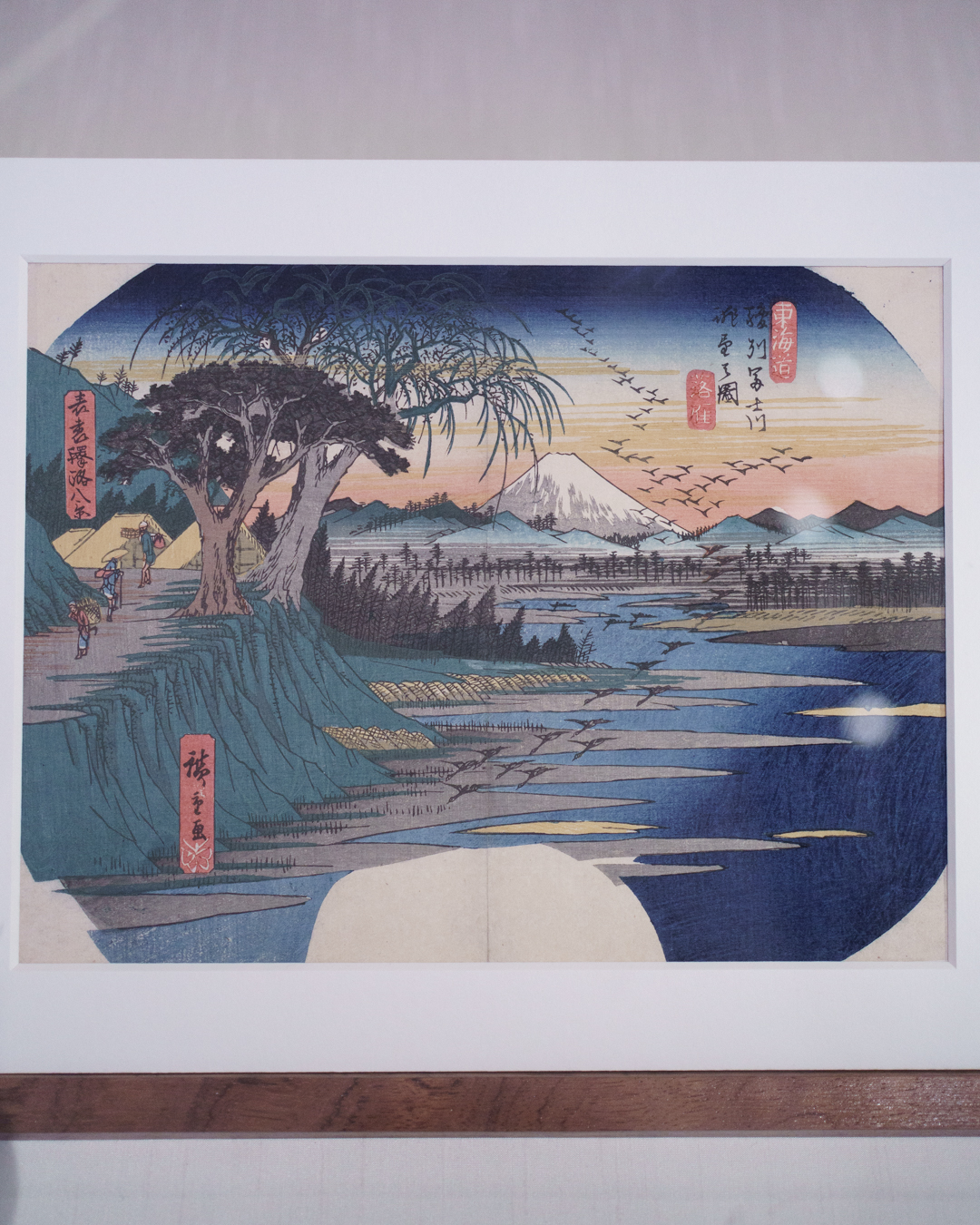

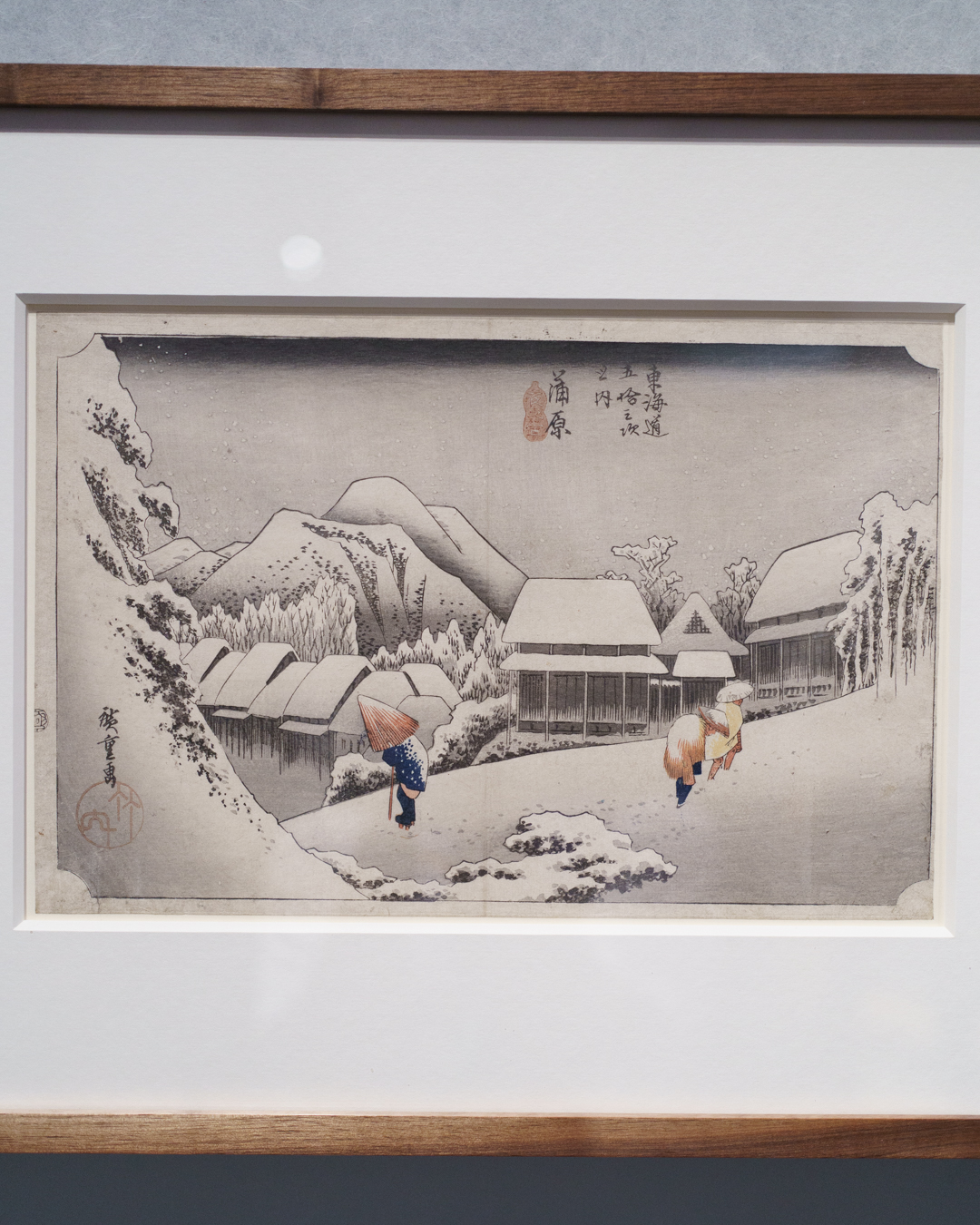

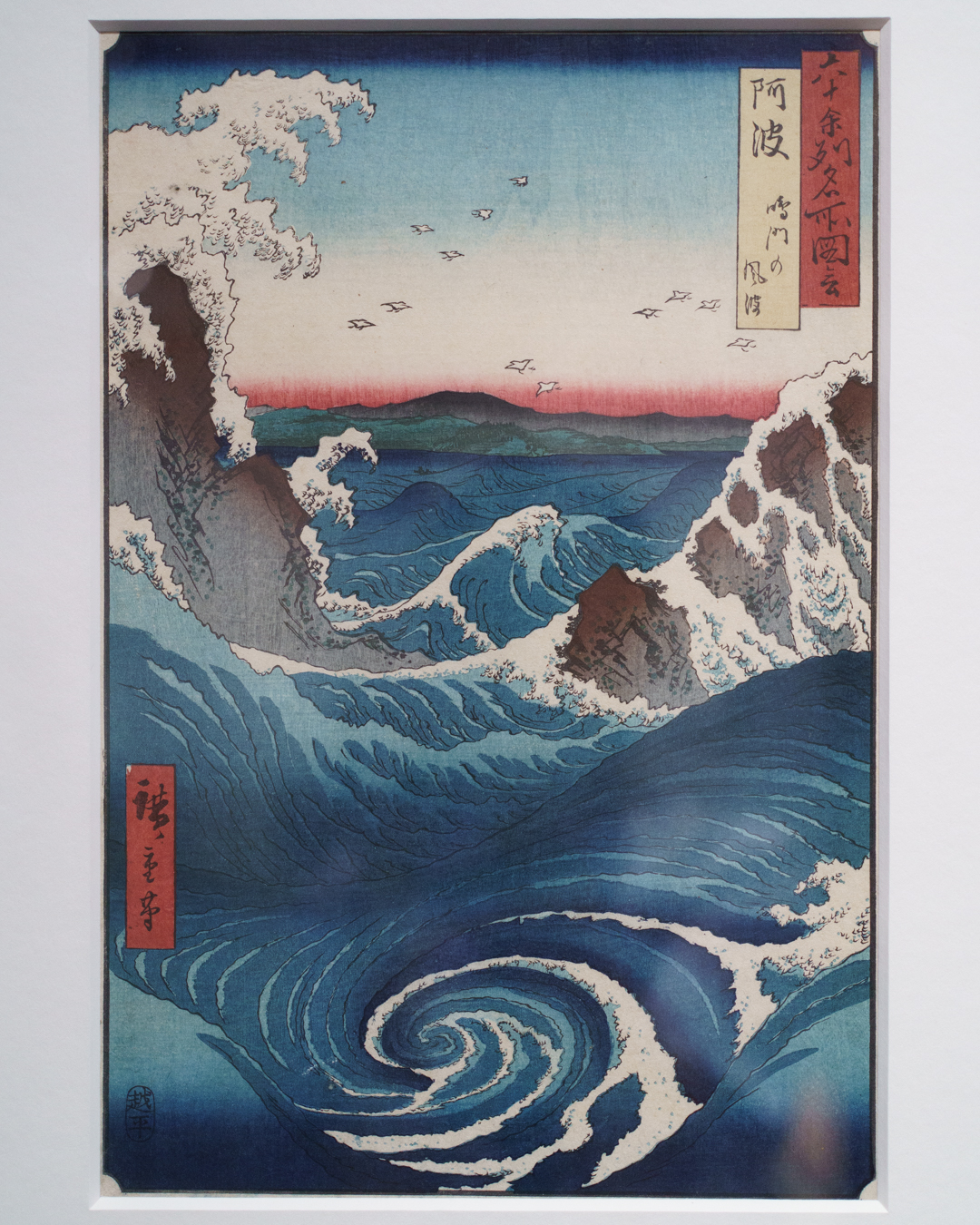

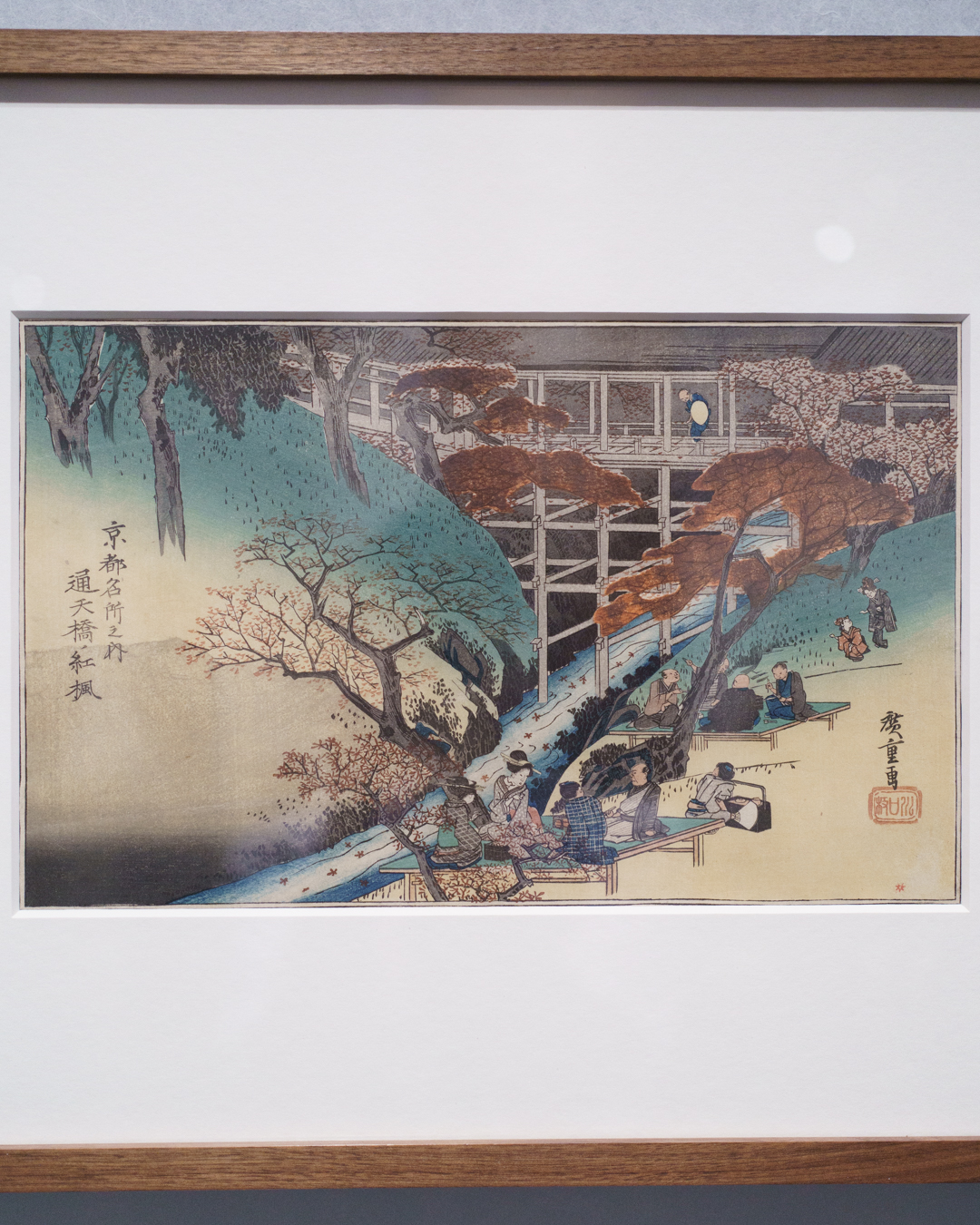

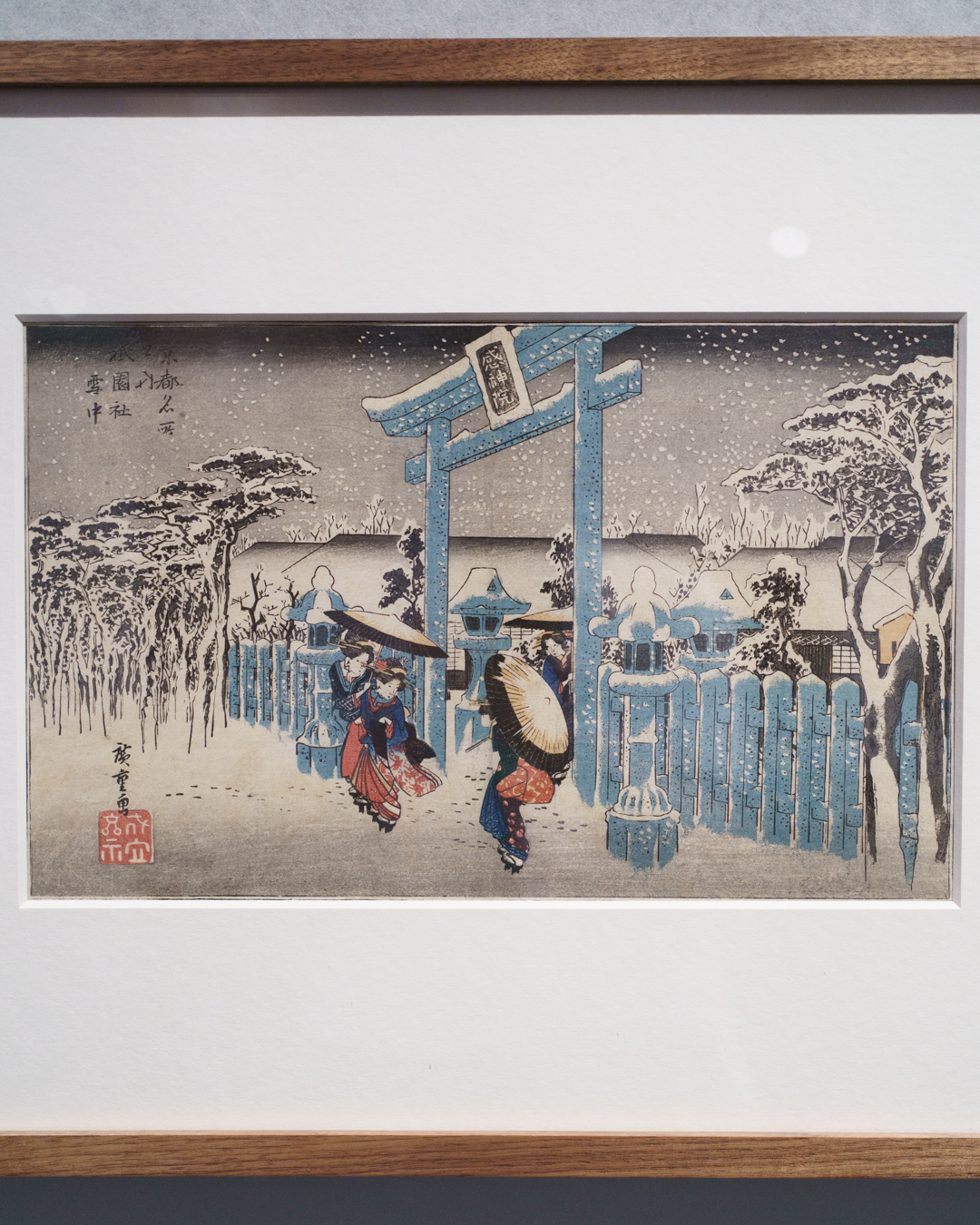

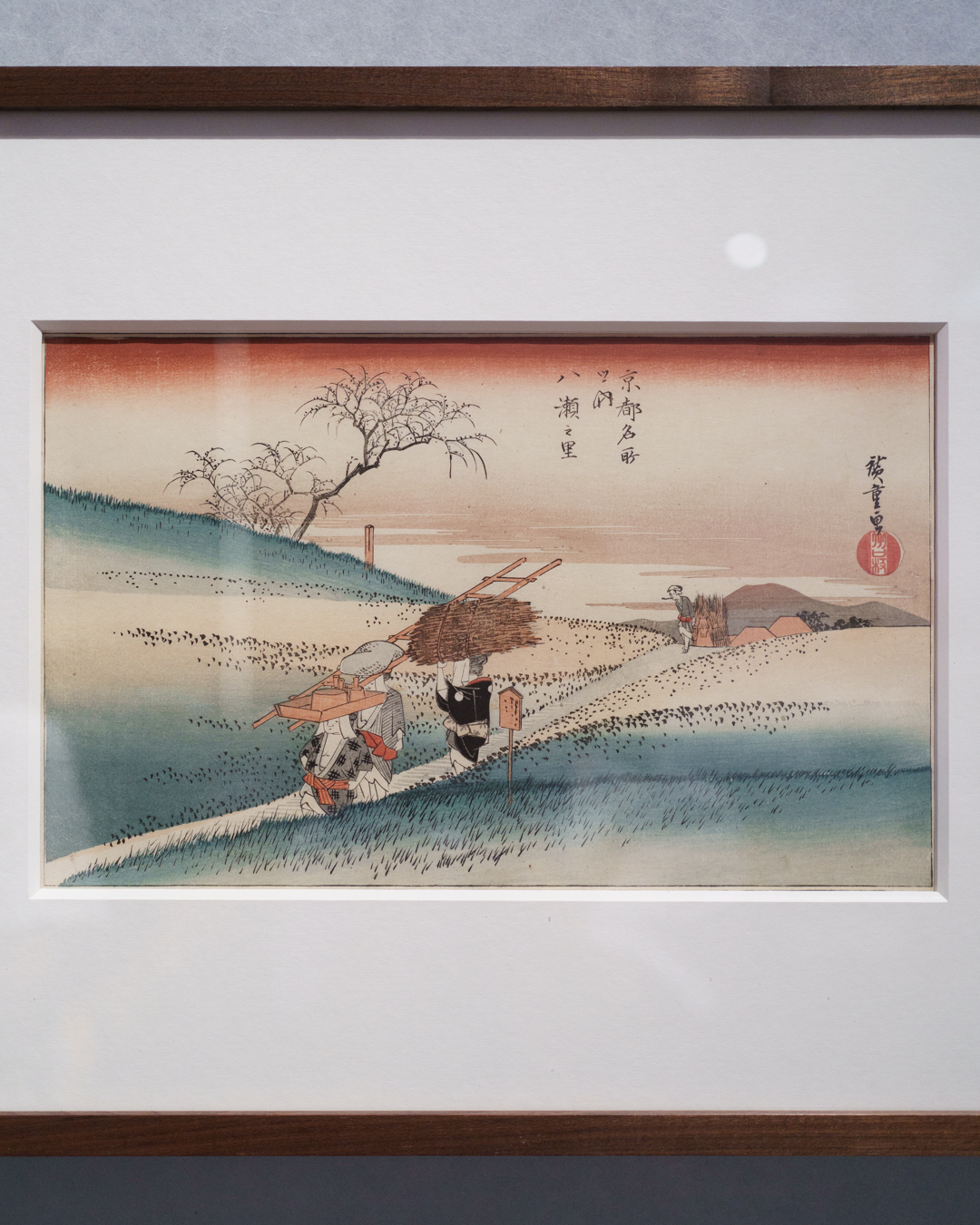

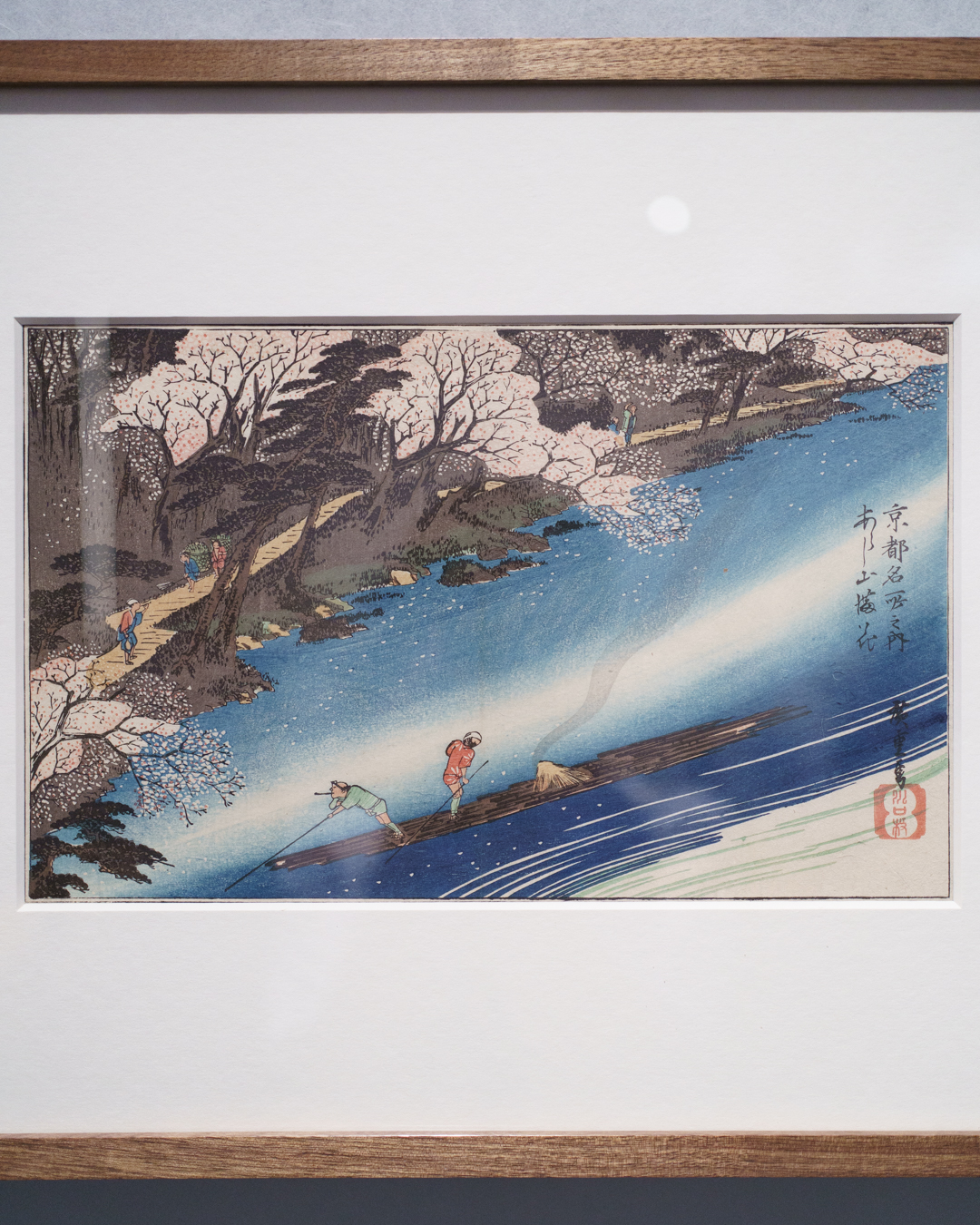

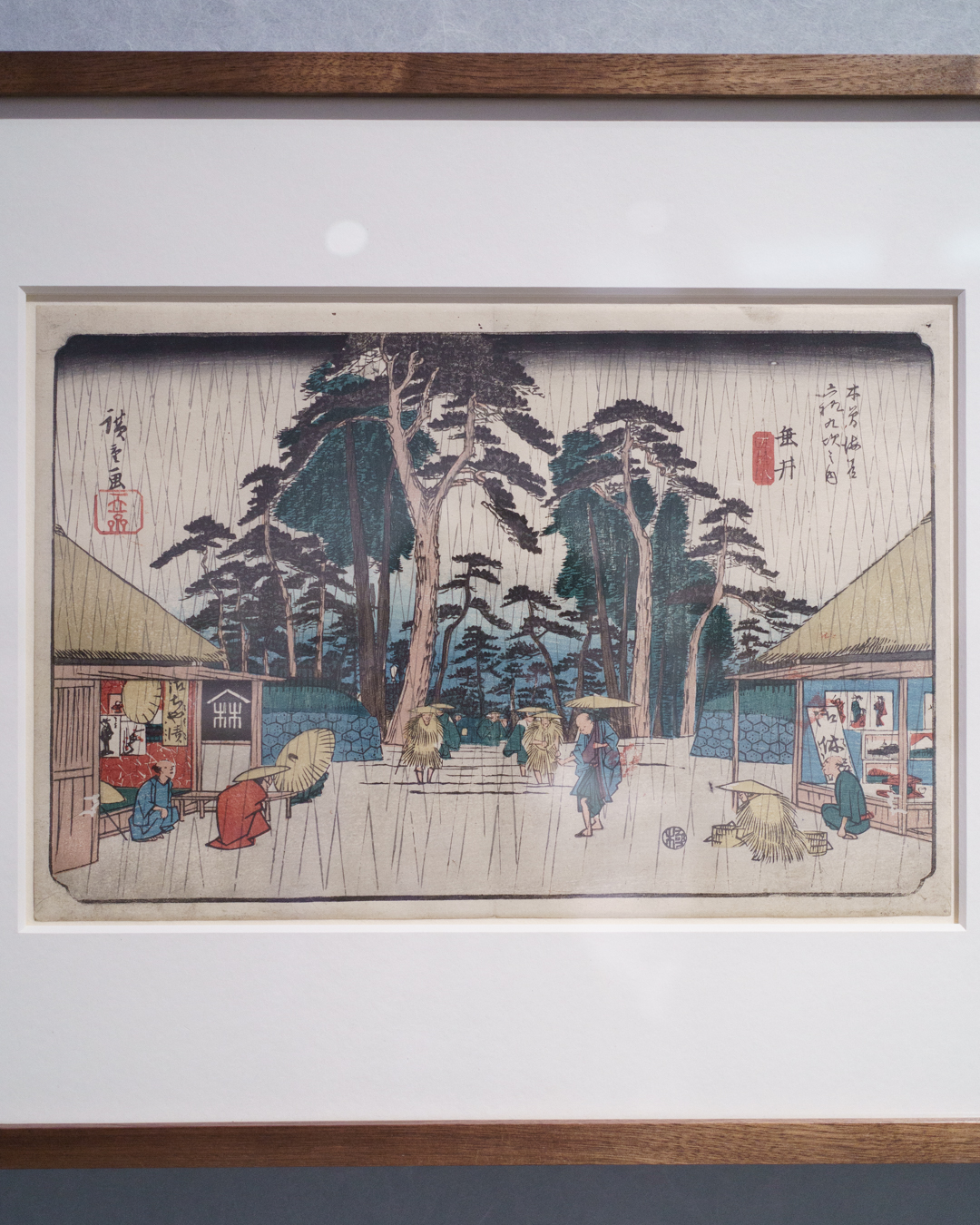

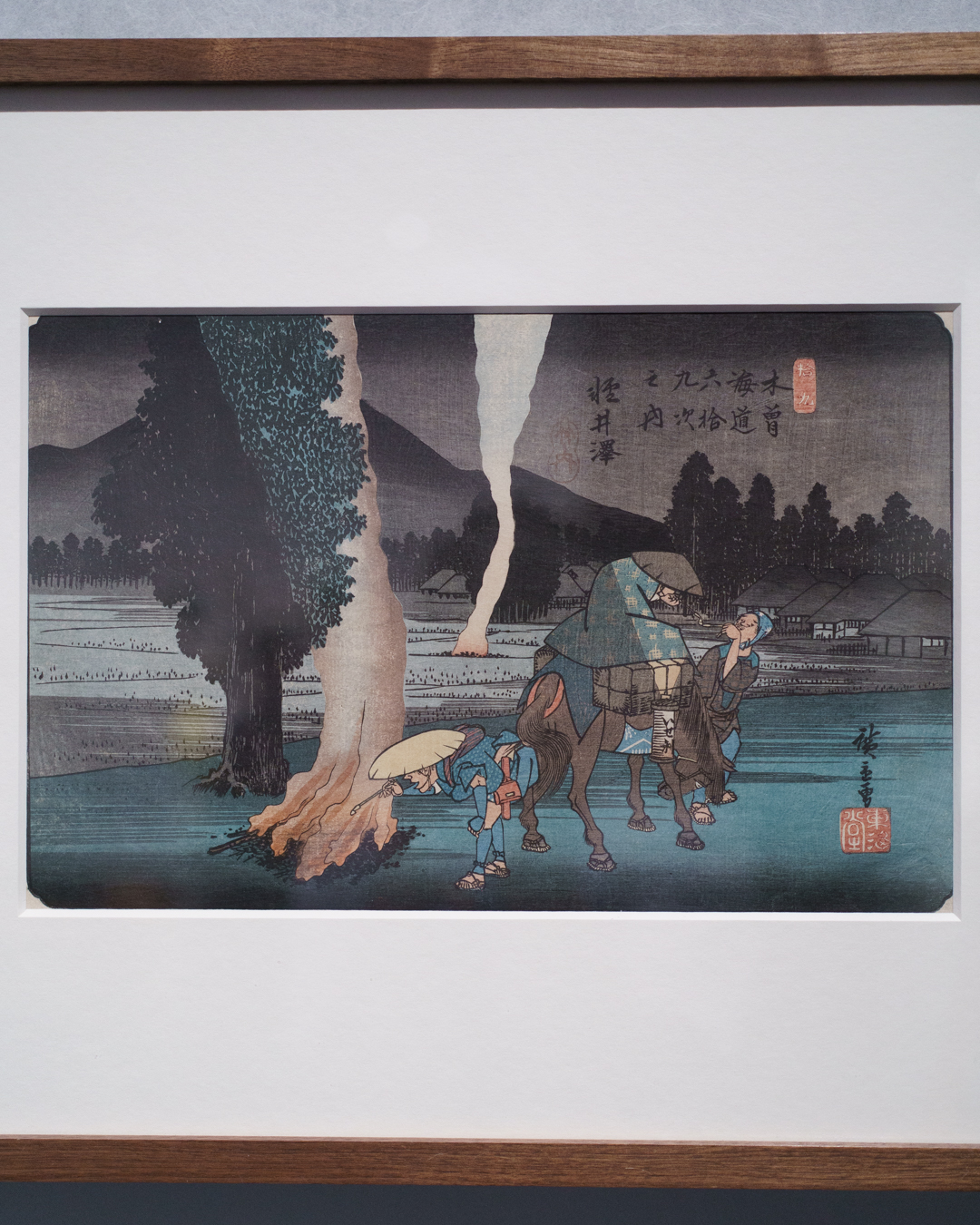

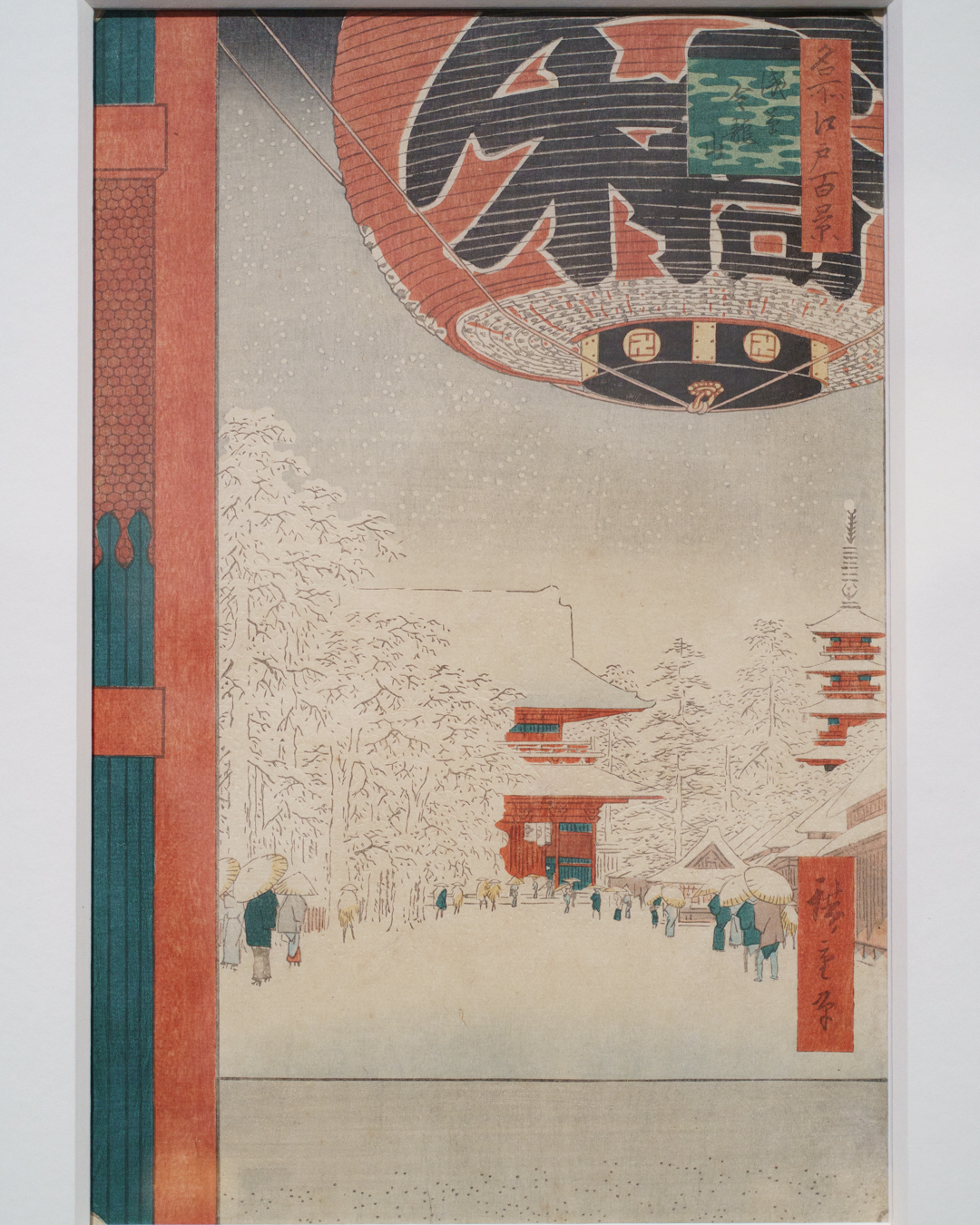

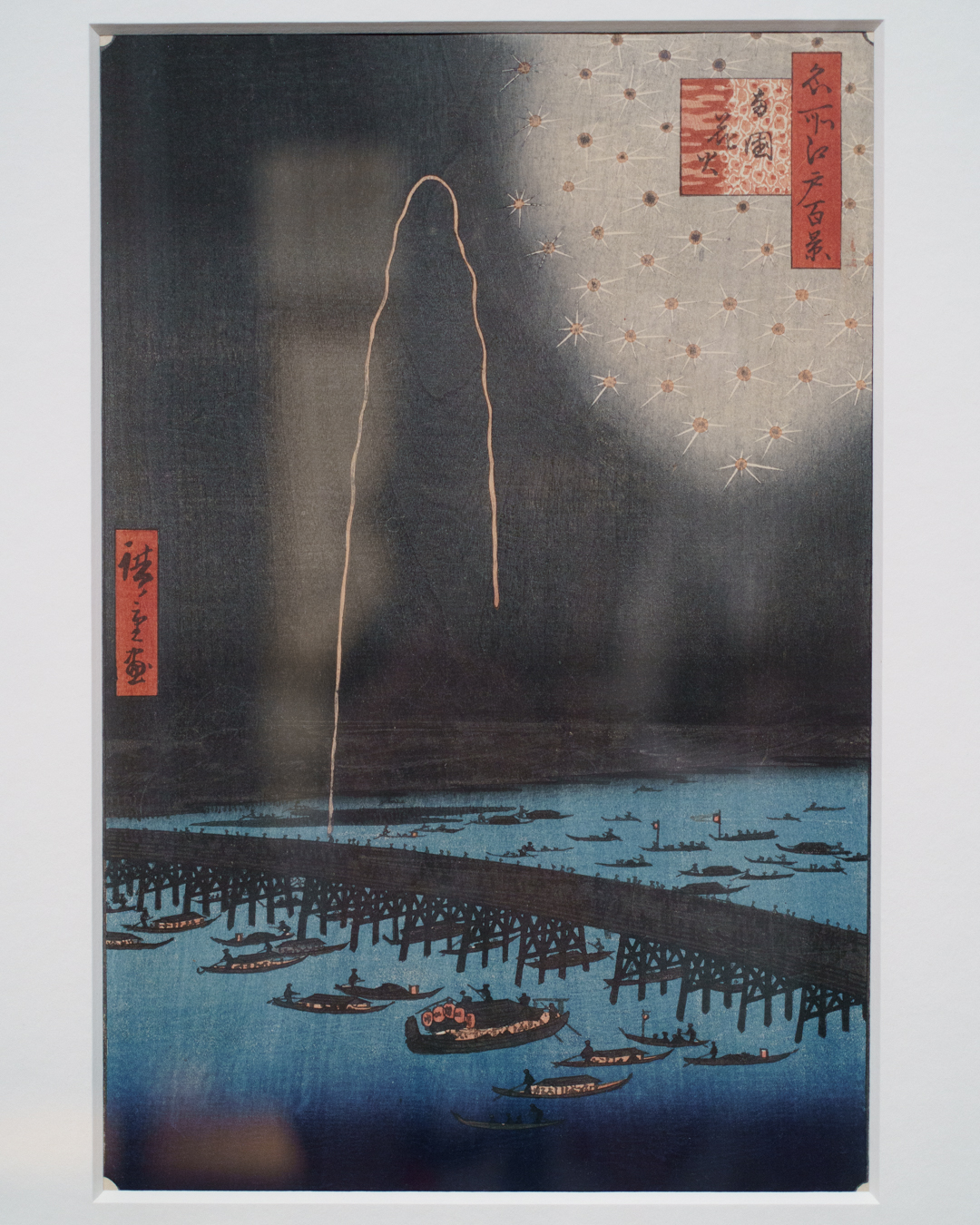

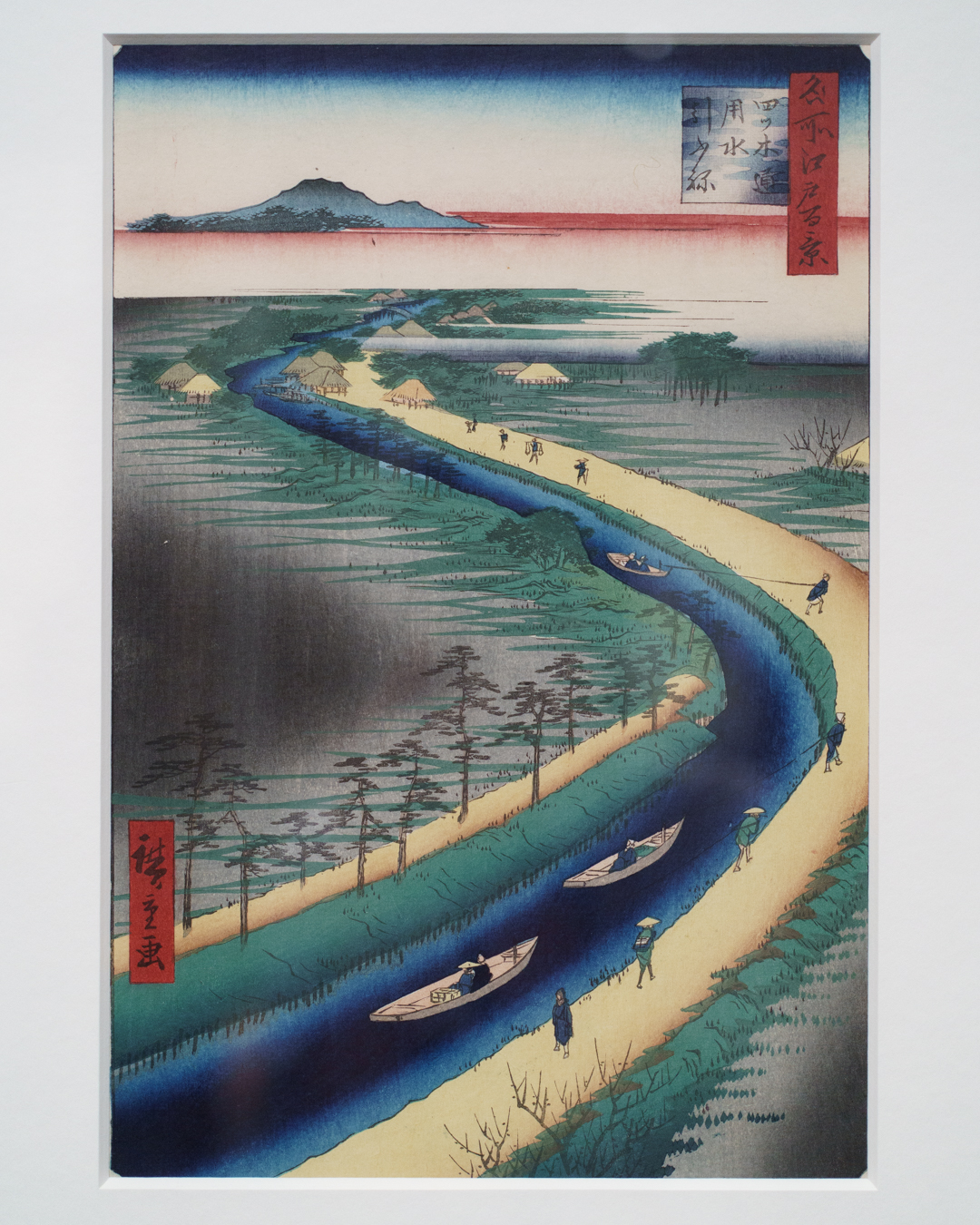

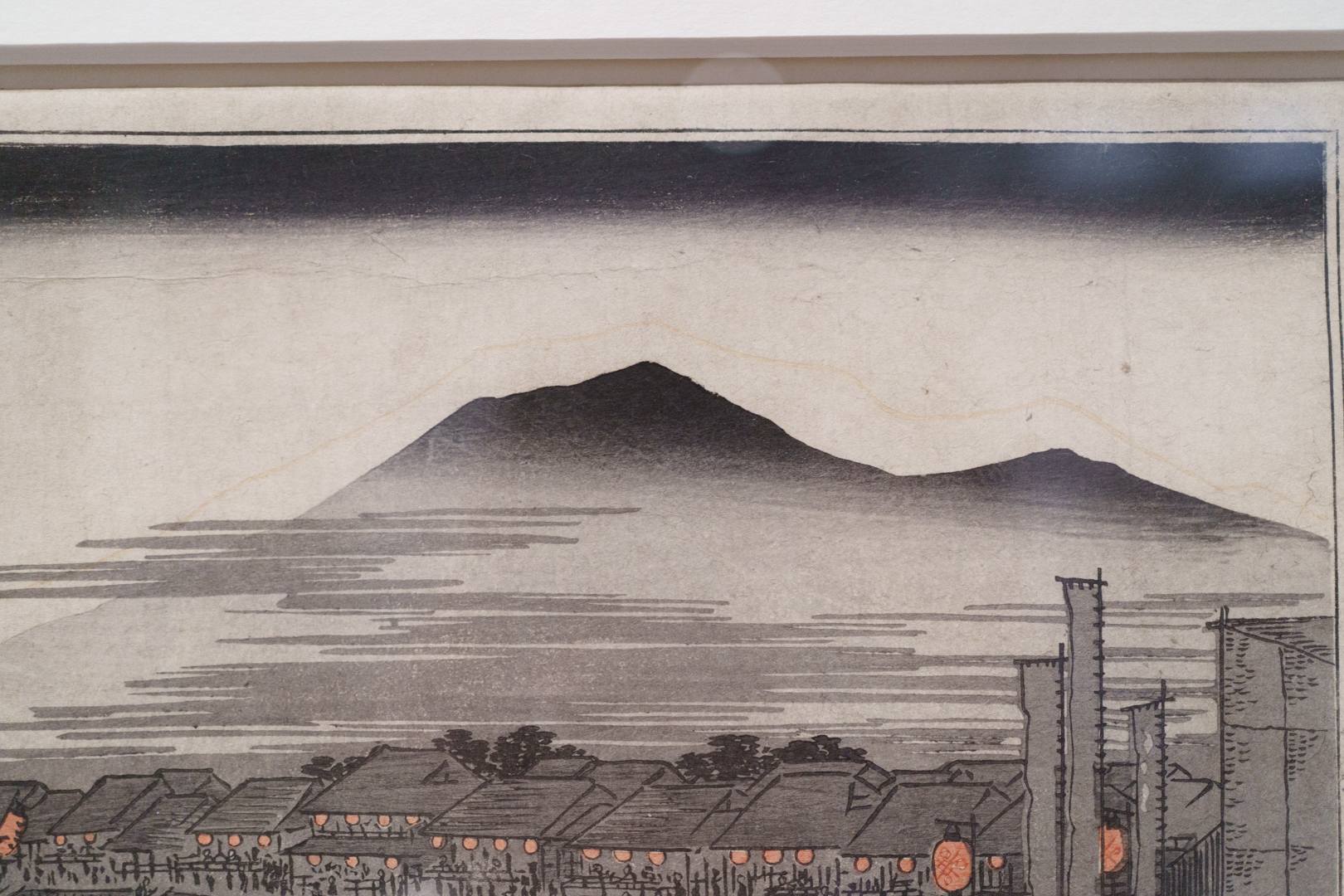

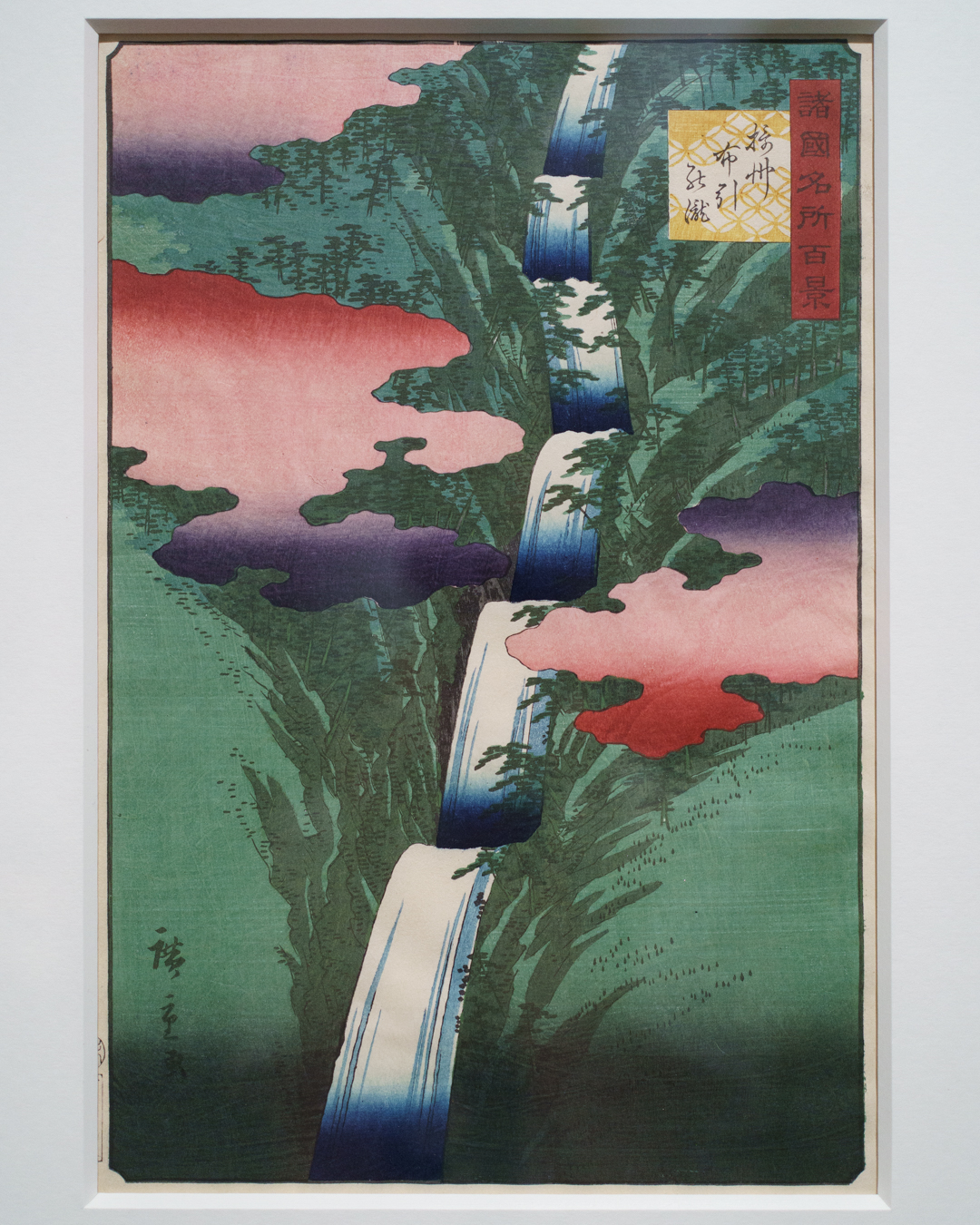

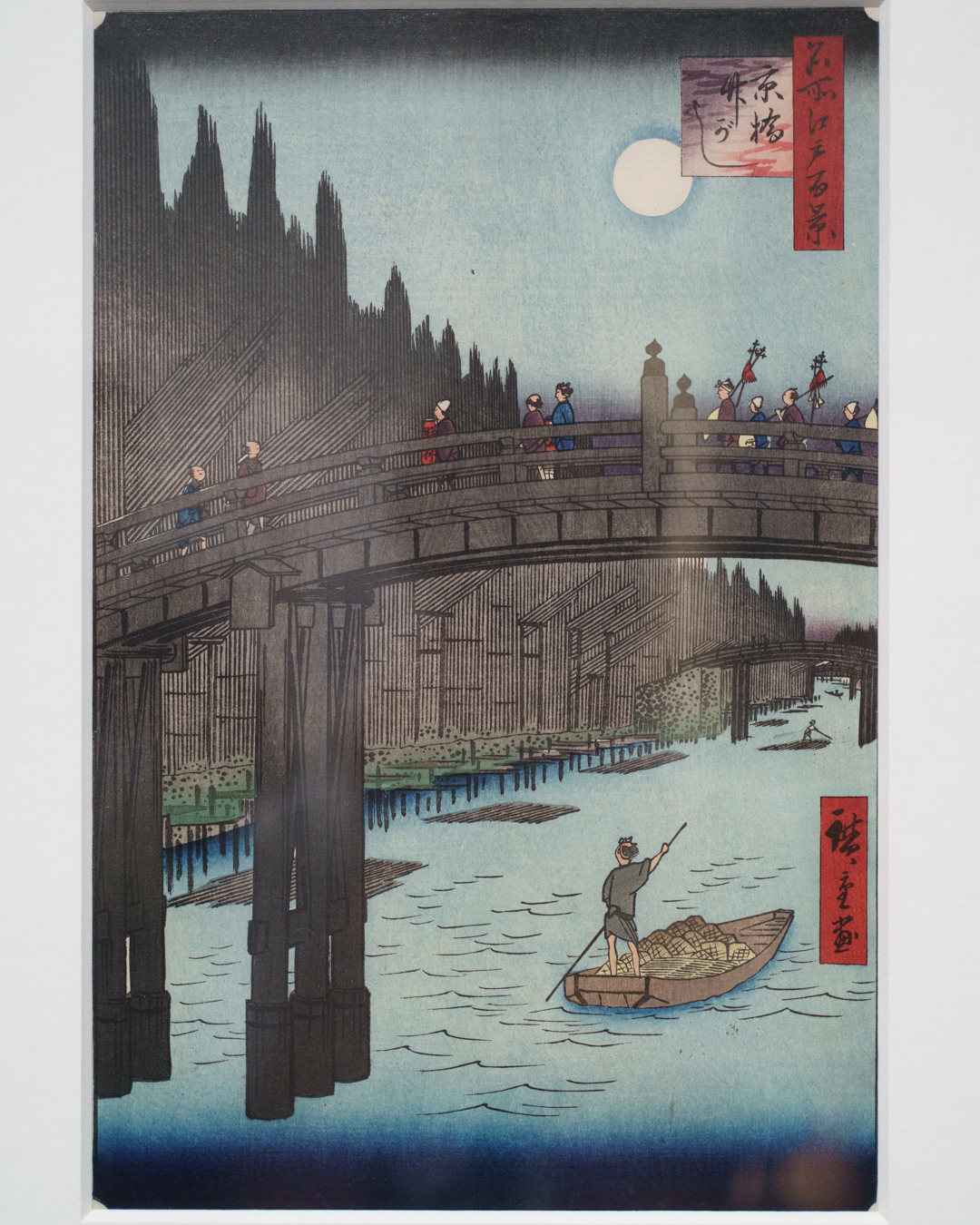

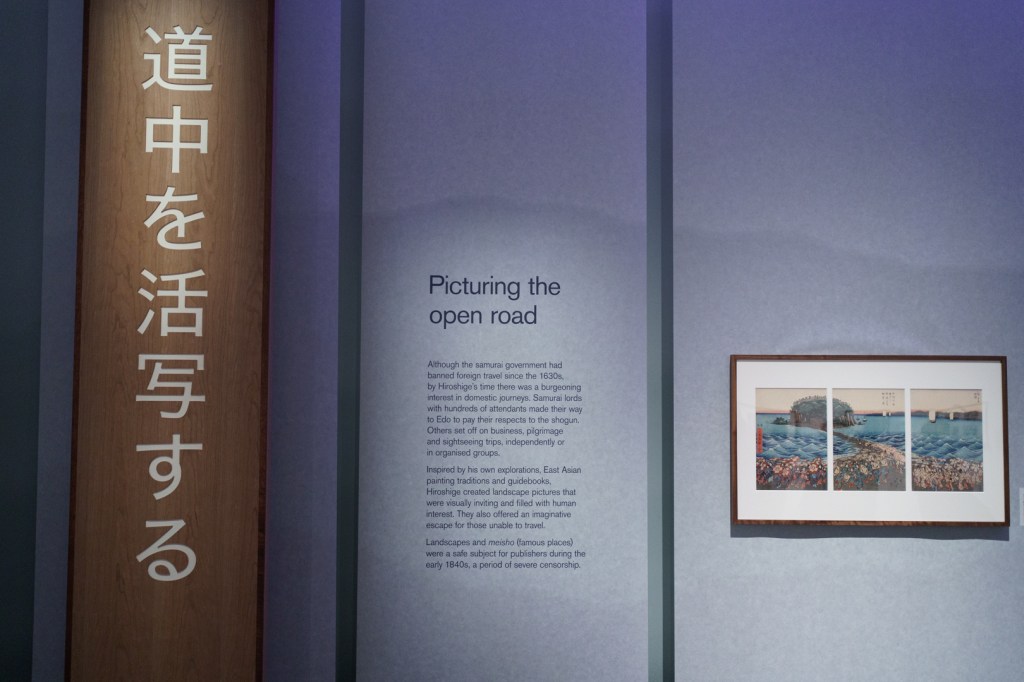

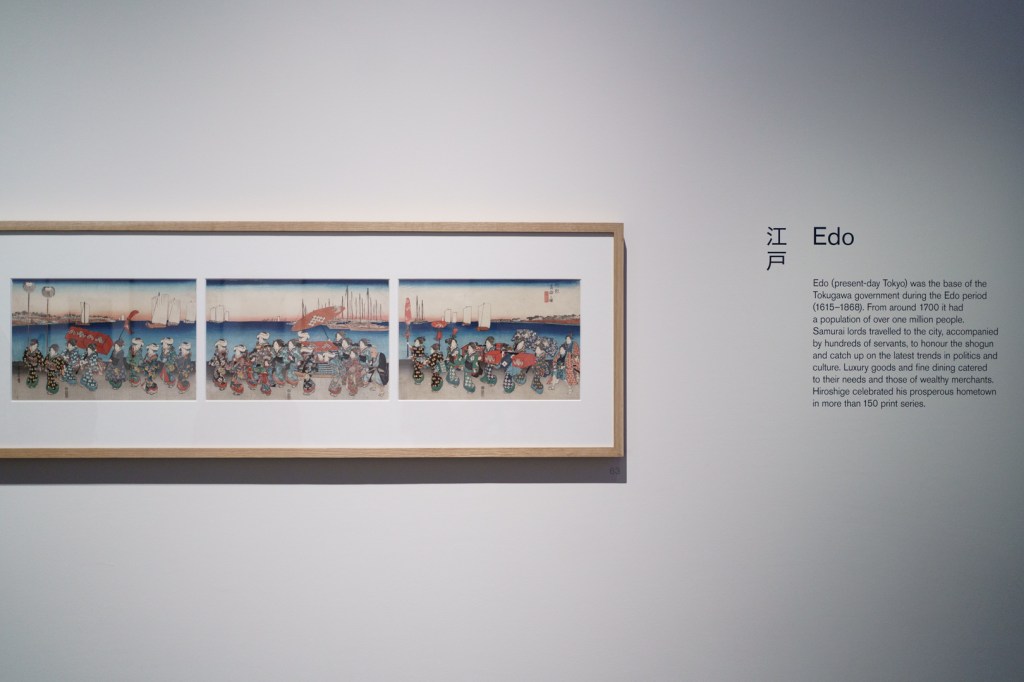

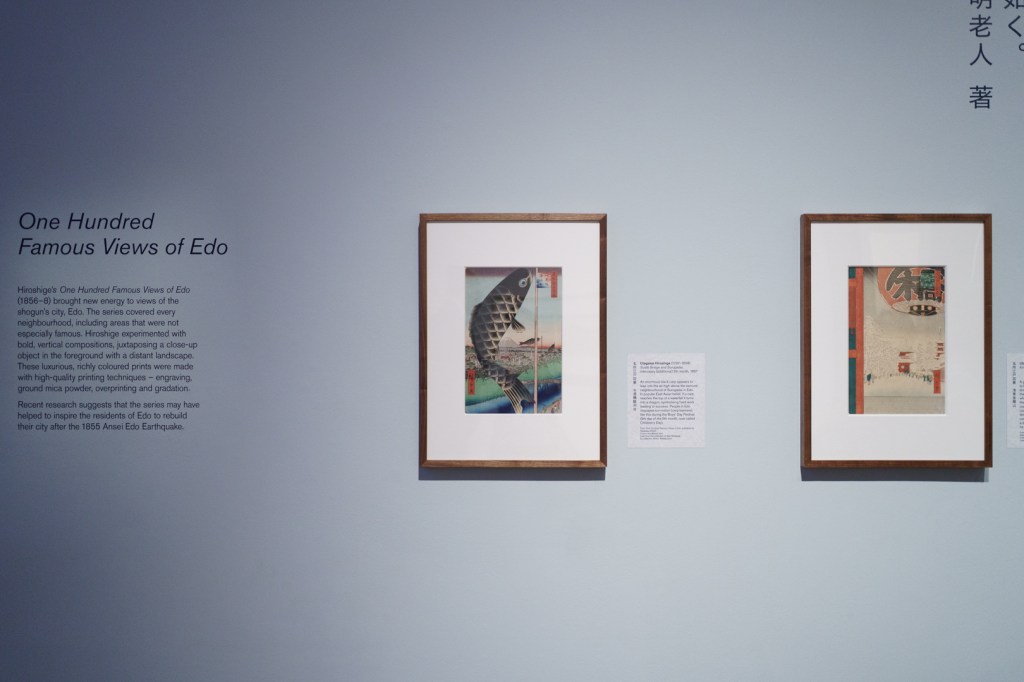

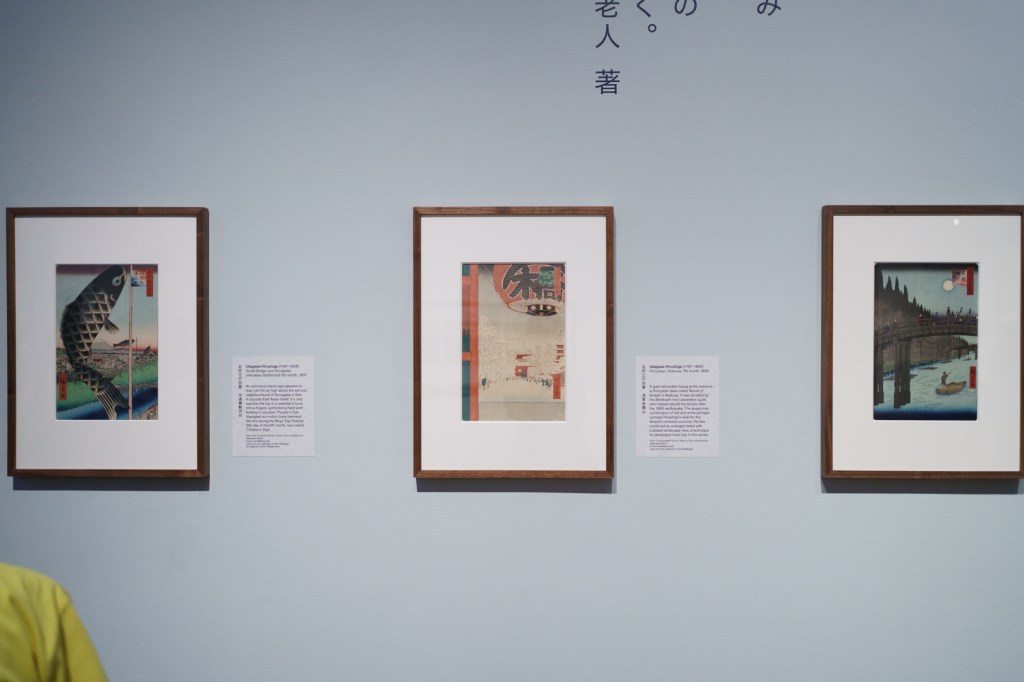

Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road at the British Museum is a remarkable survey of prints by Utagawa Hiroshige I (born Andō Tokutarō), the younger, more graceful counterpart to the graphically bold Katsushika Hokusai. Hiroshige practically cornered the market in travel prints with several major print series like the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, the Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kiso Highway, and the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

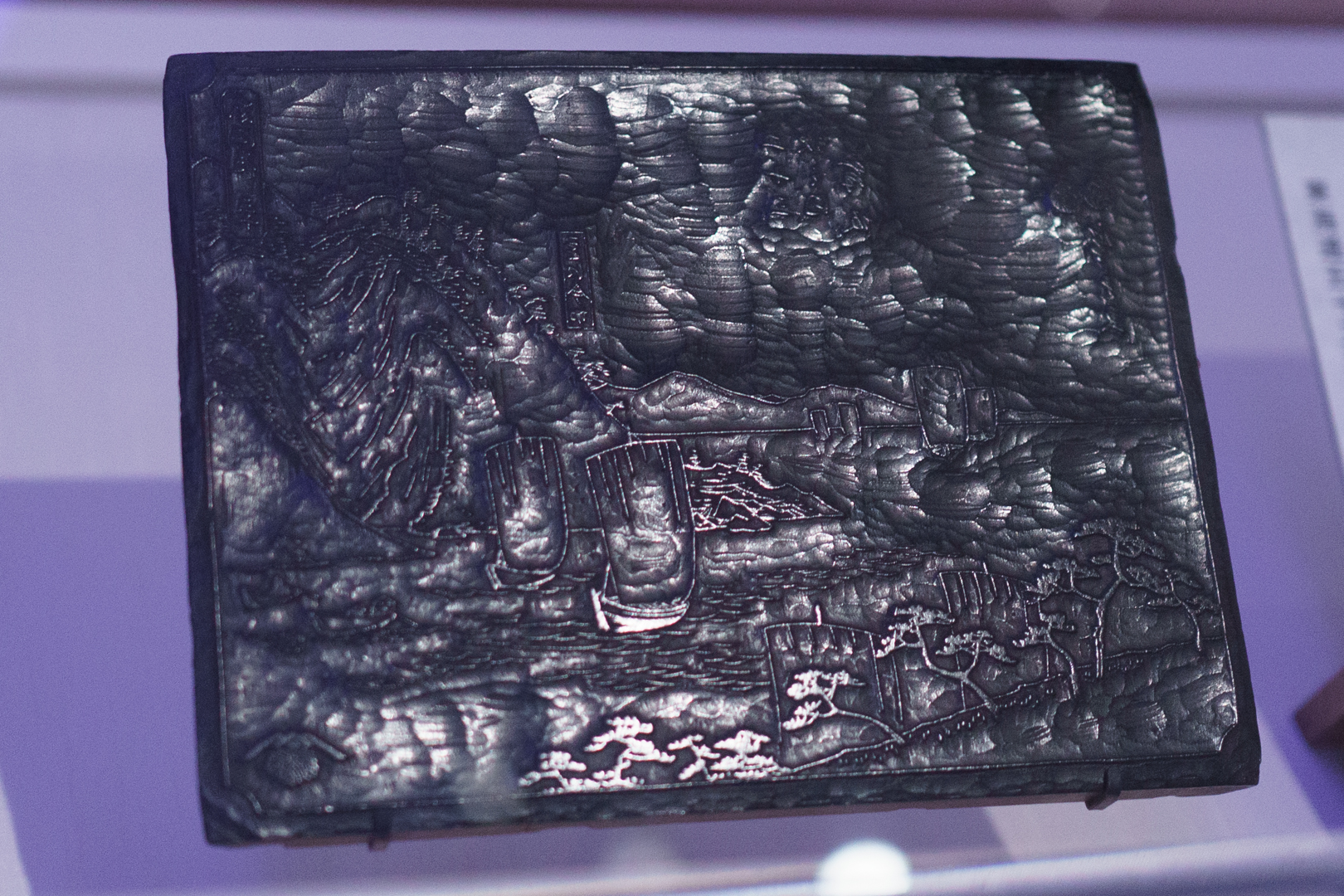

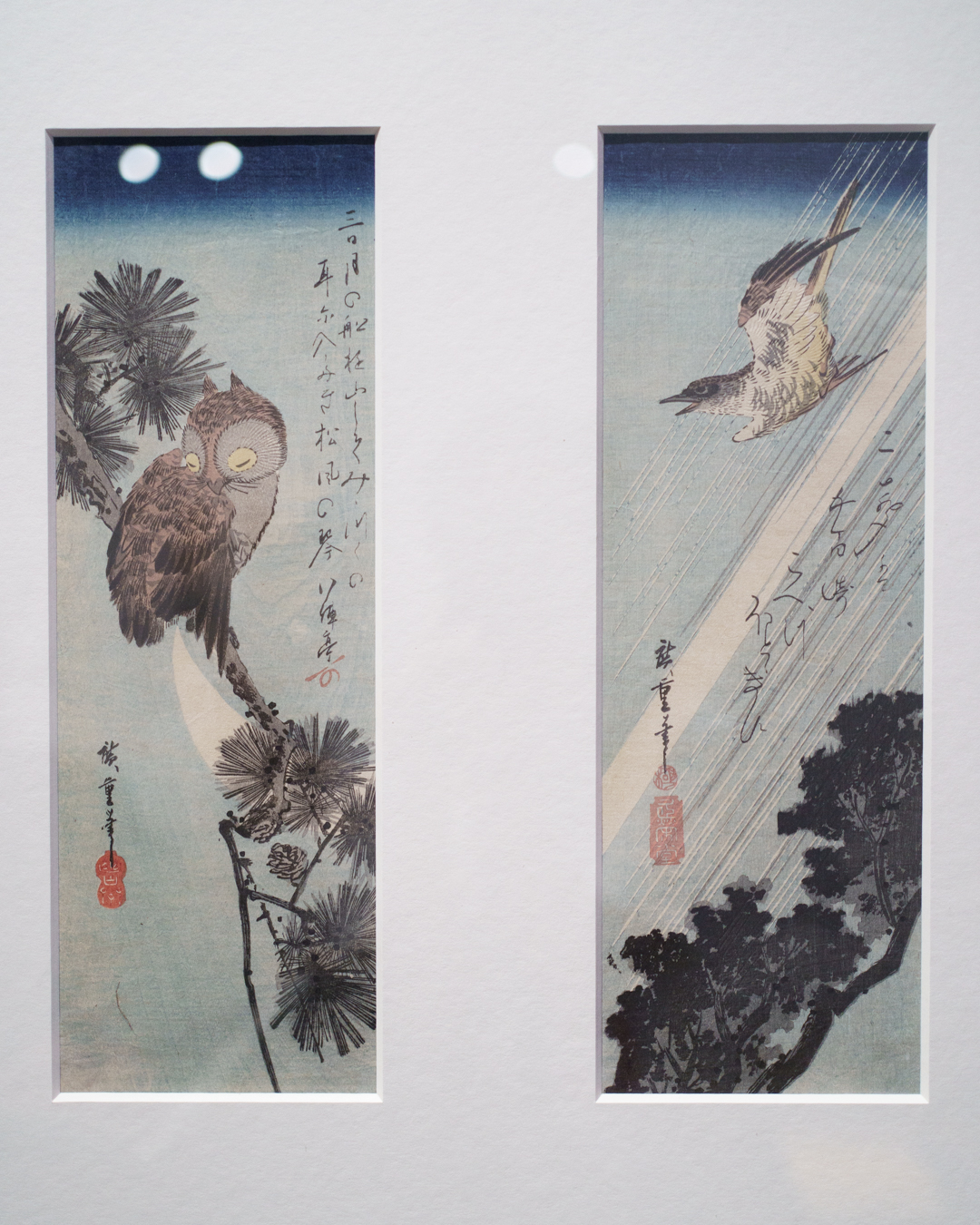

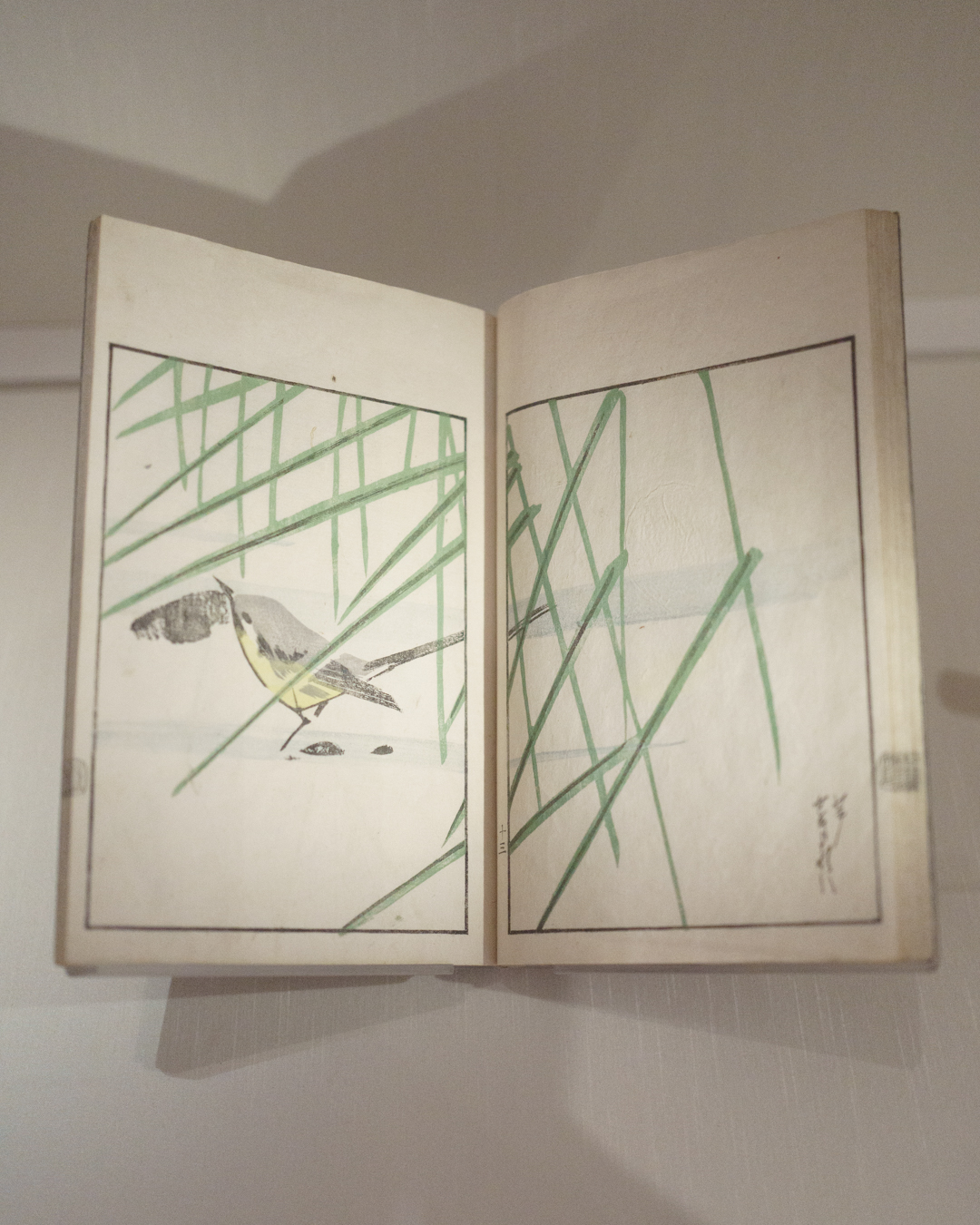

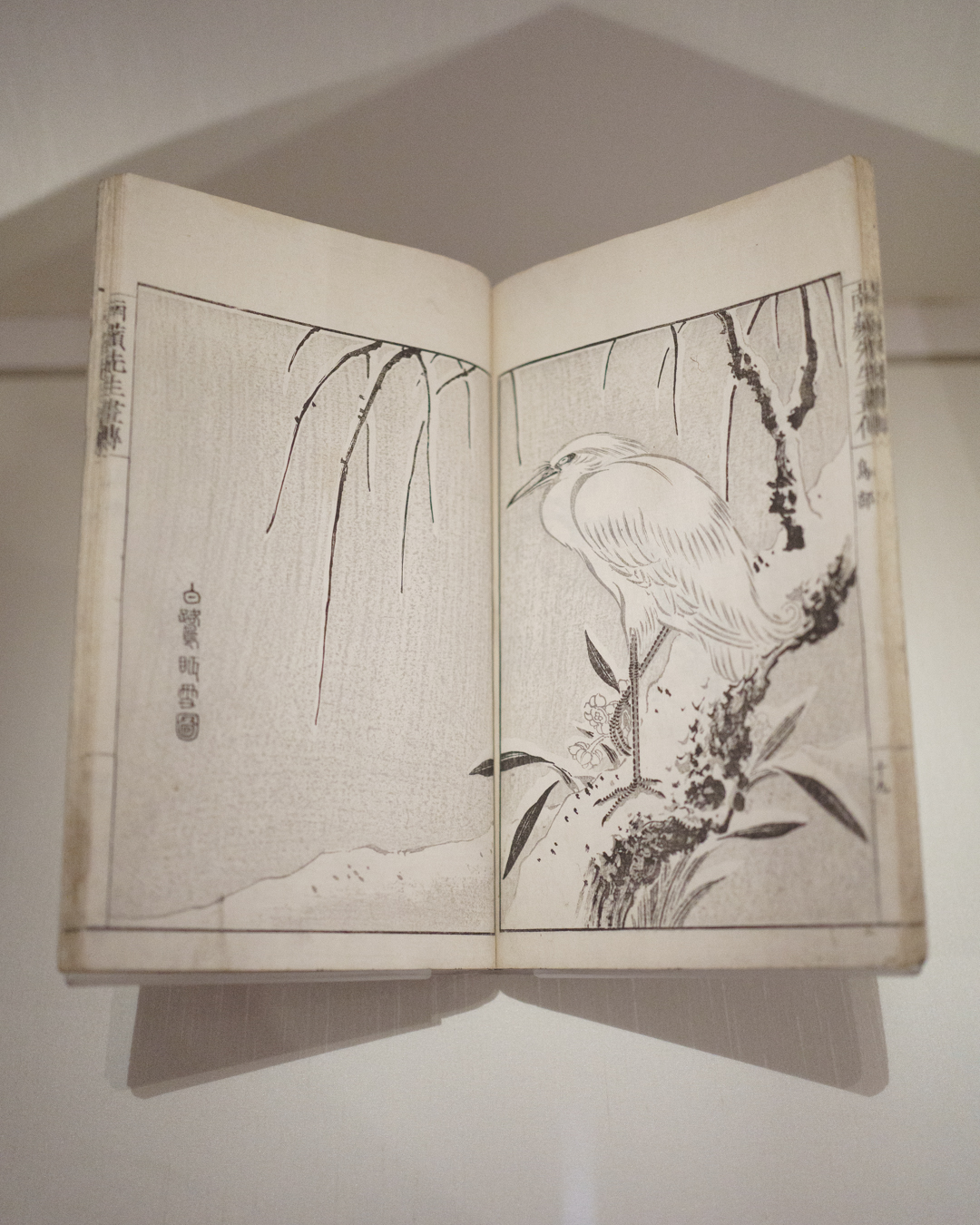

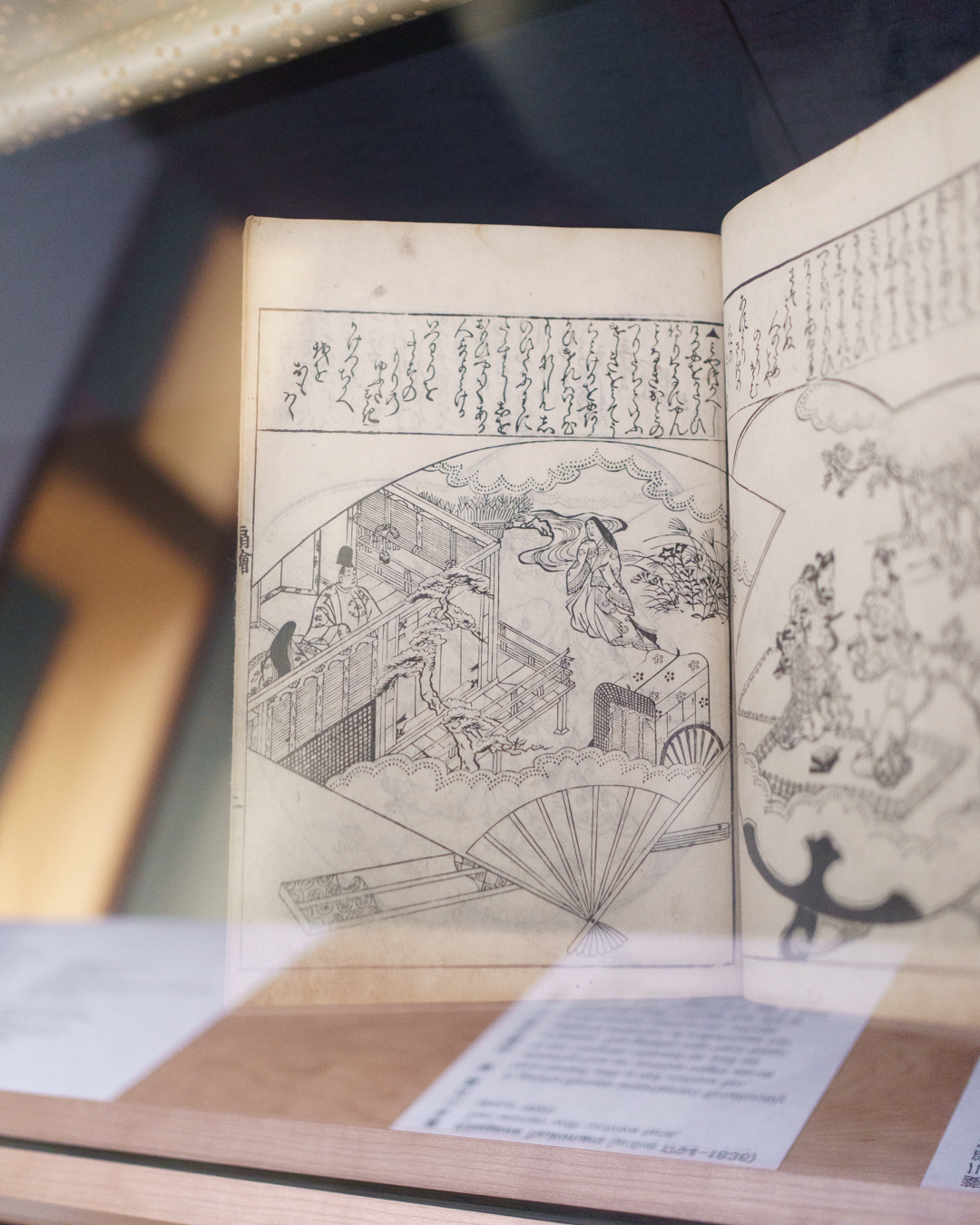

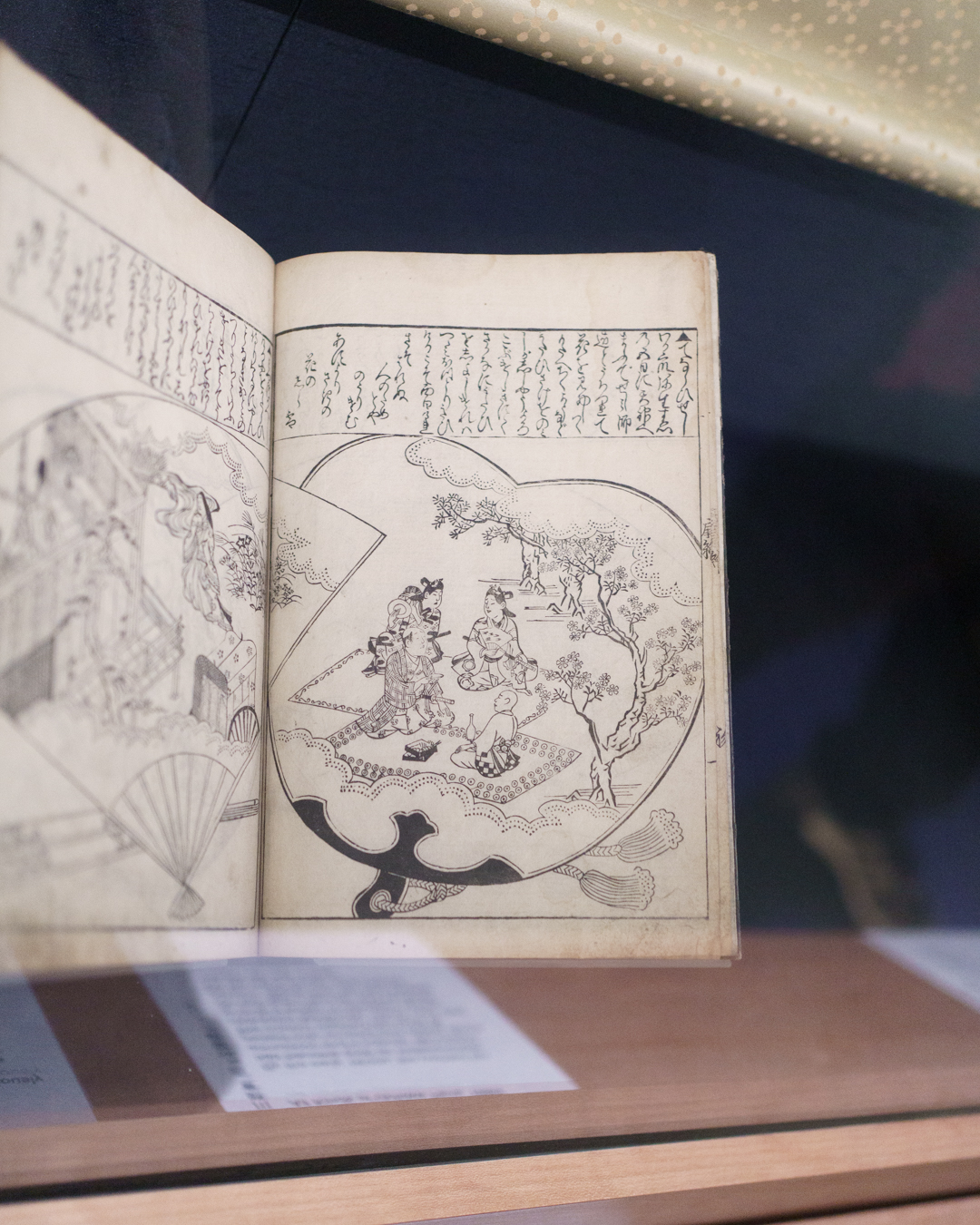

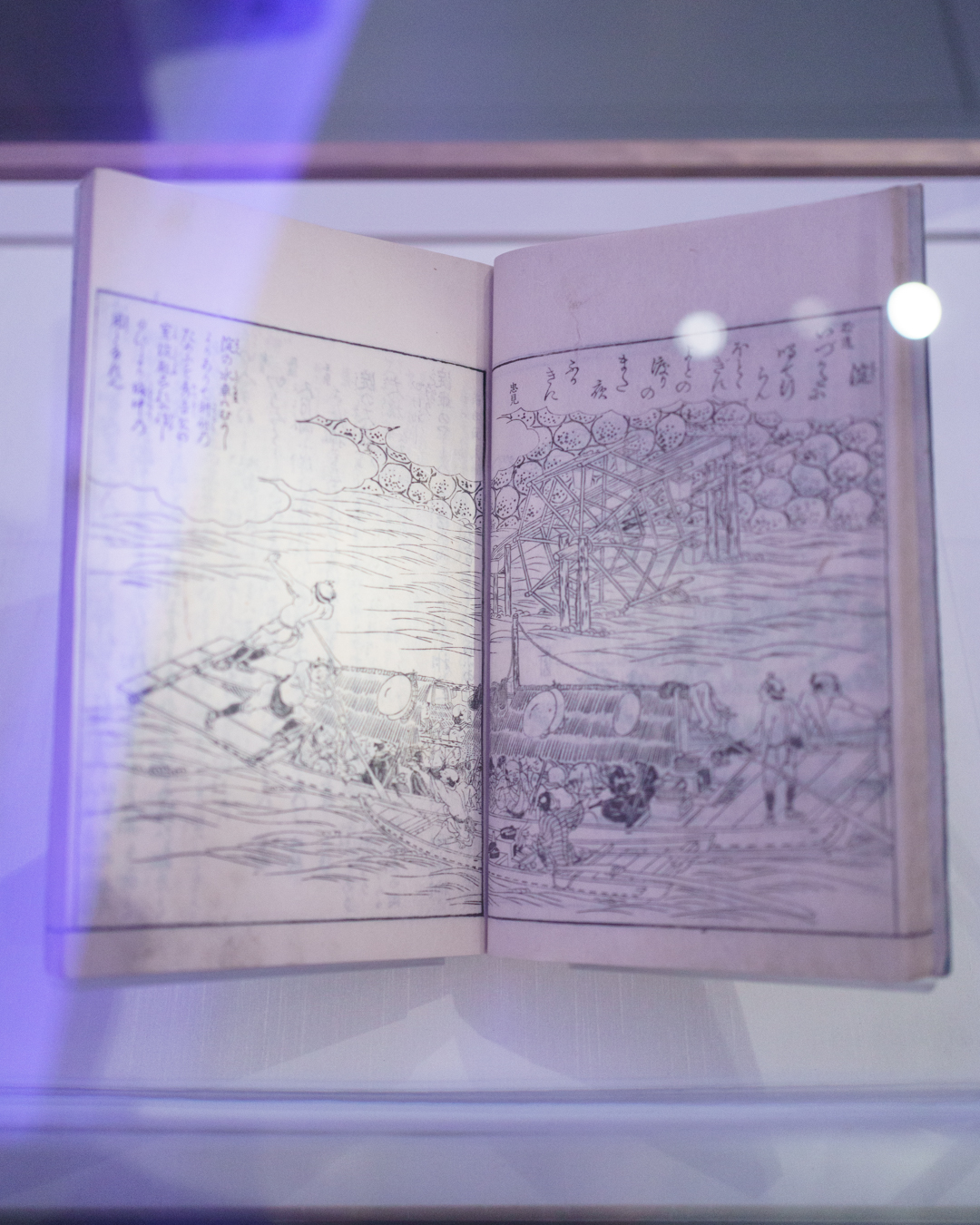

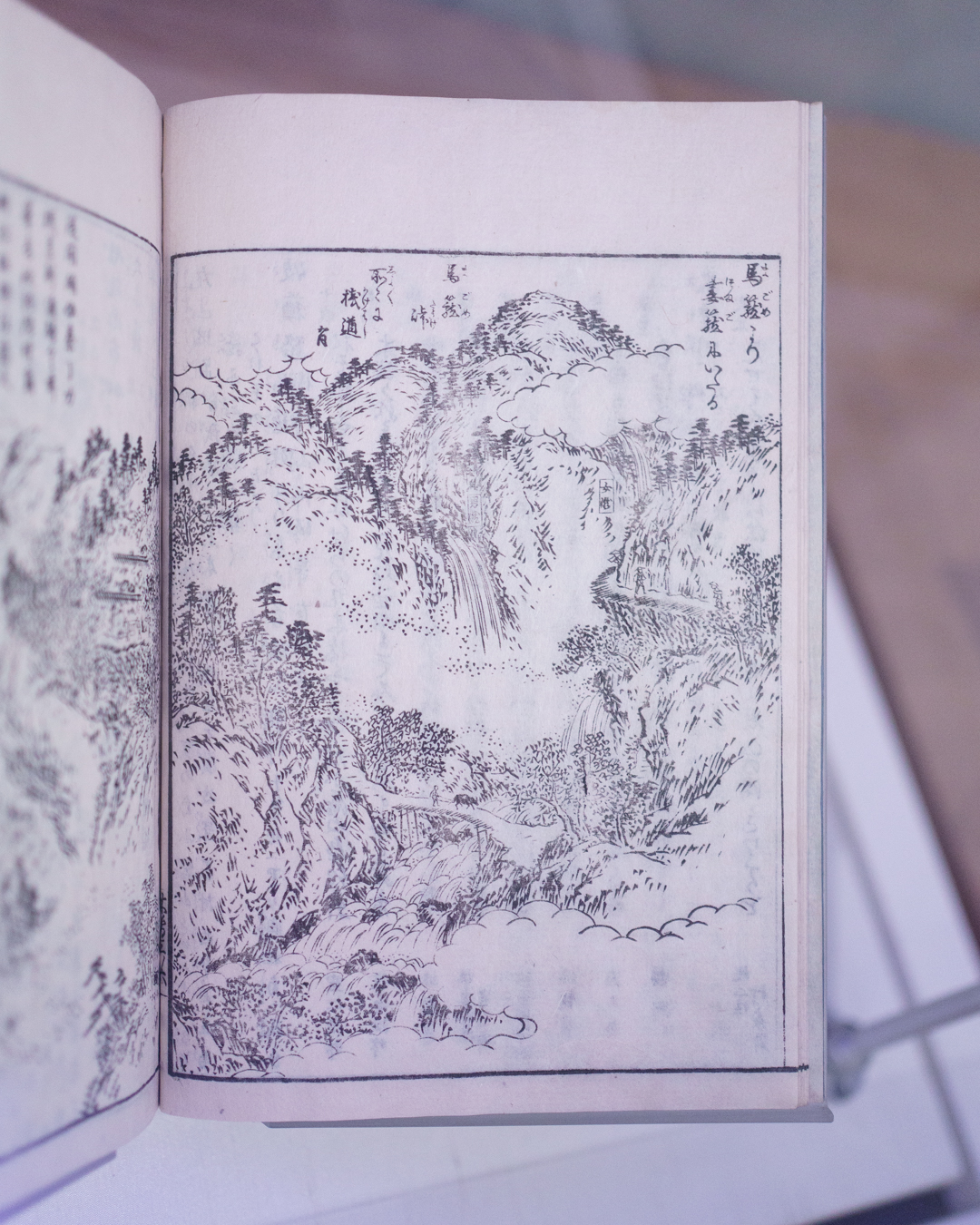

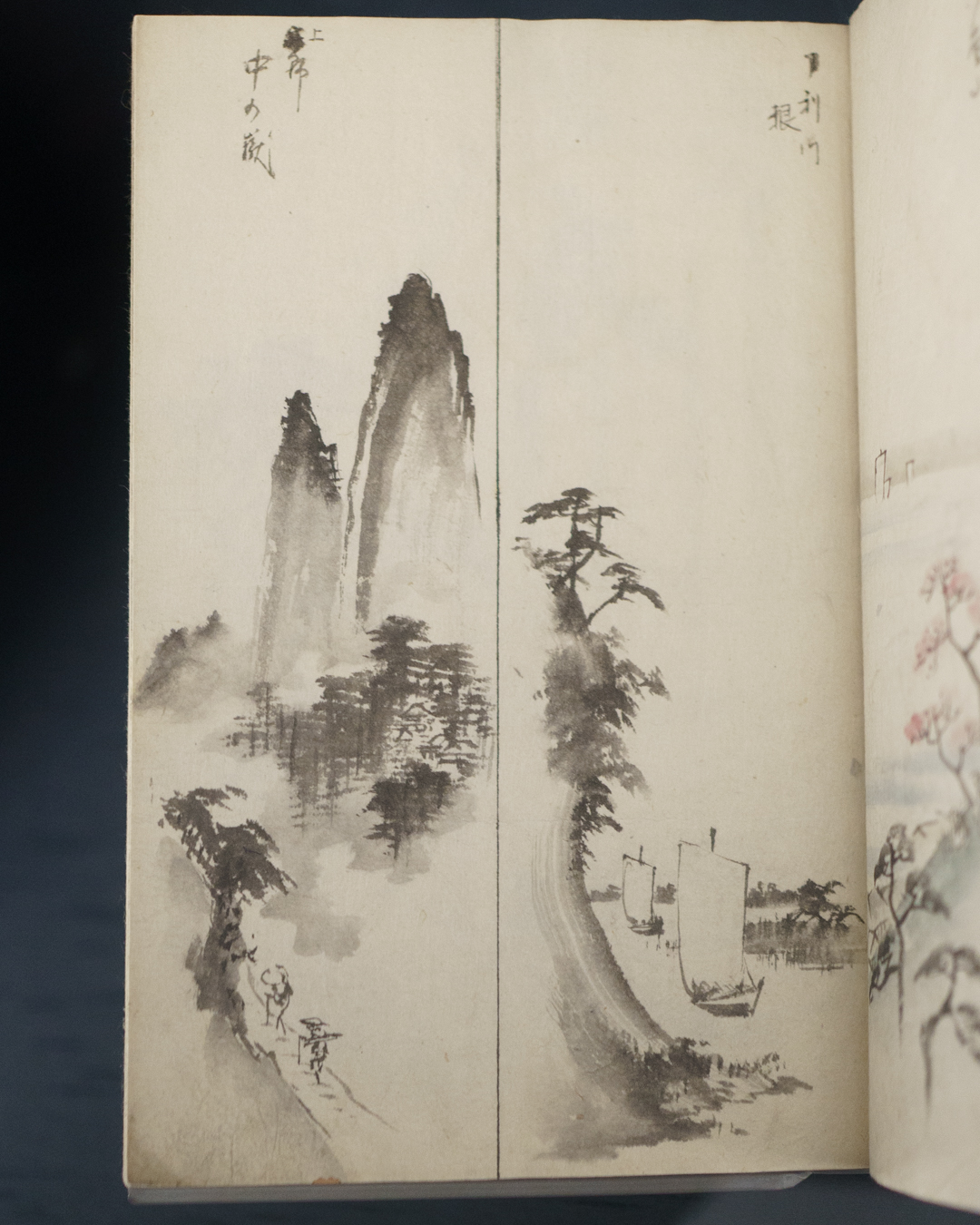

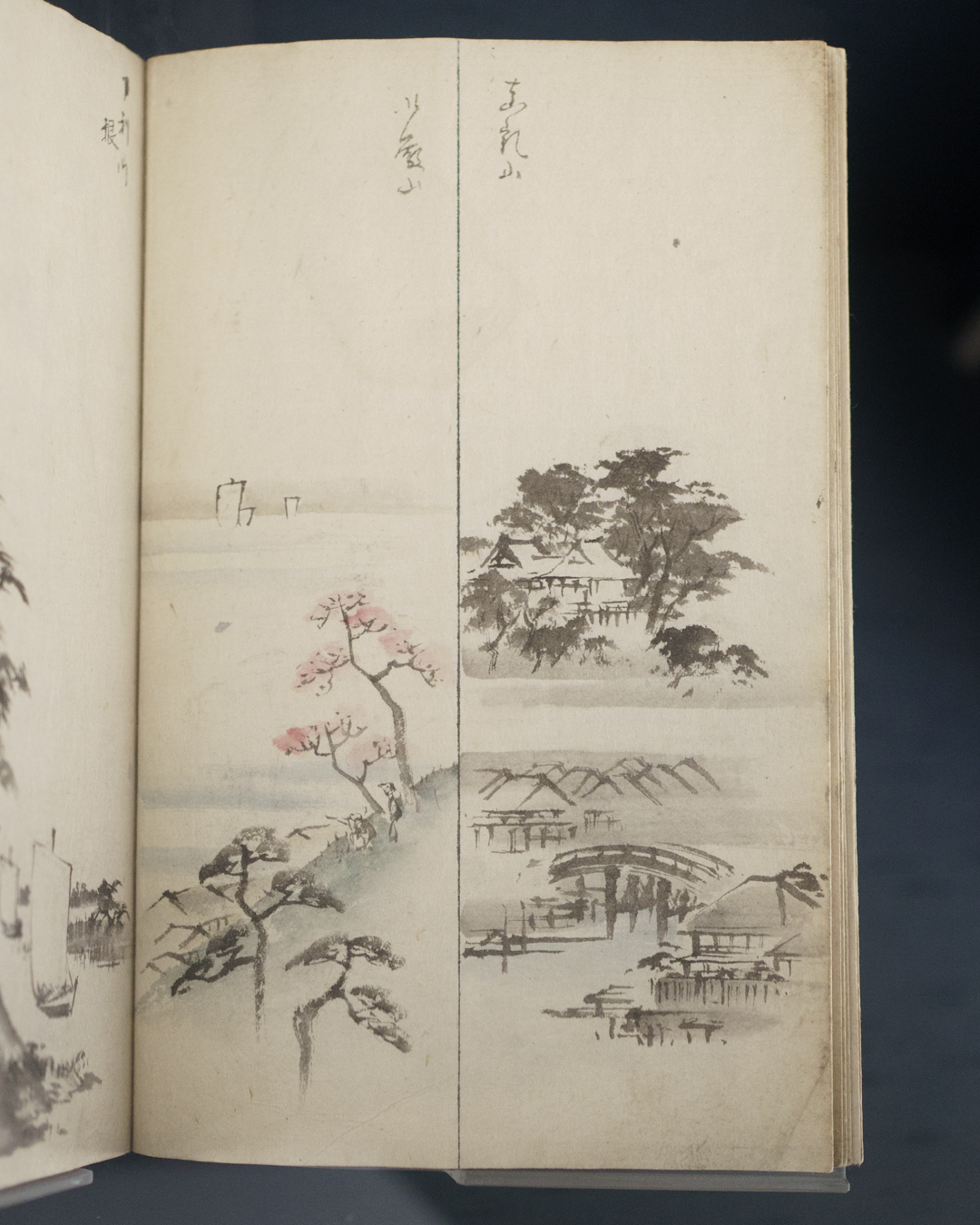

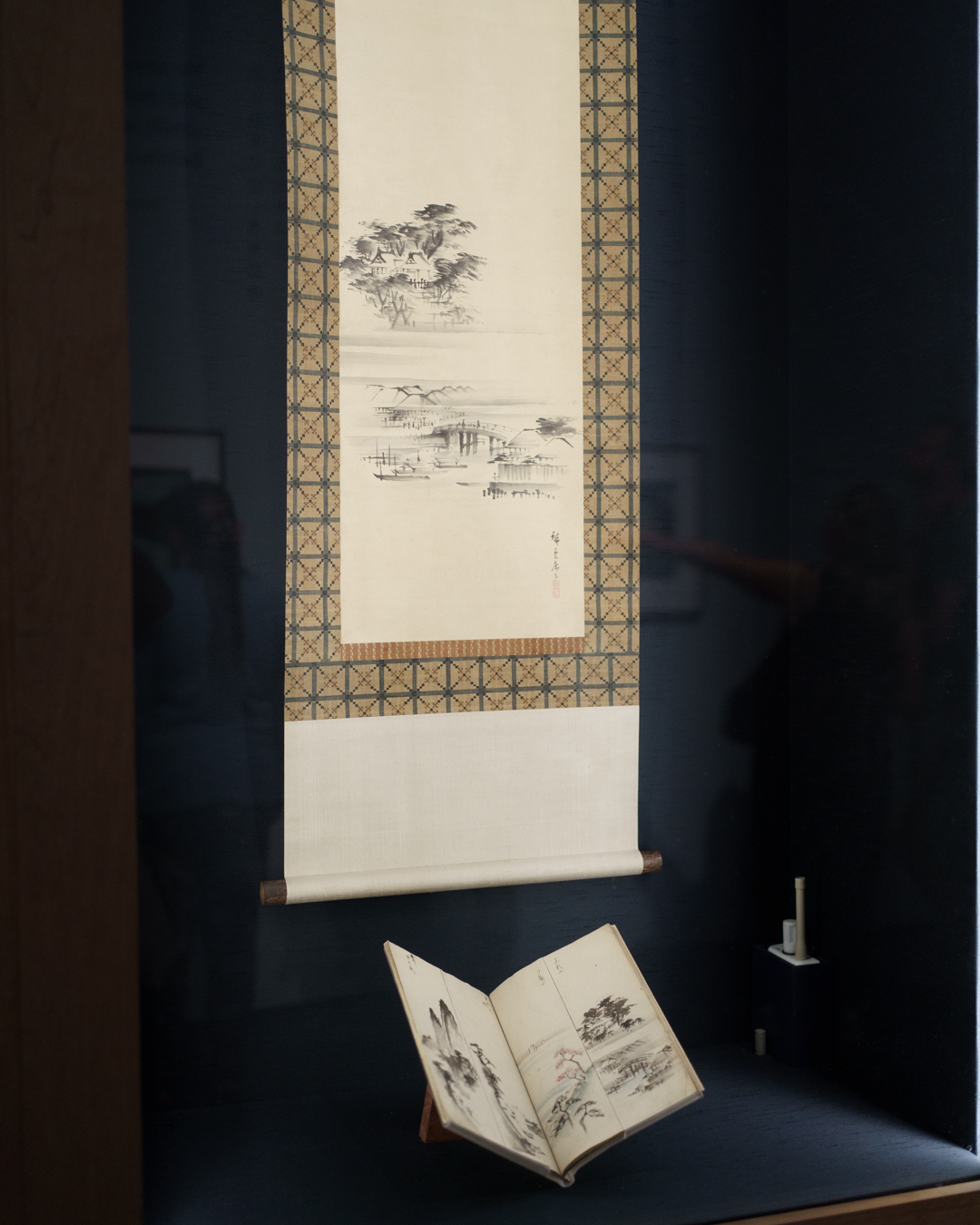

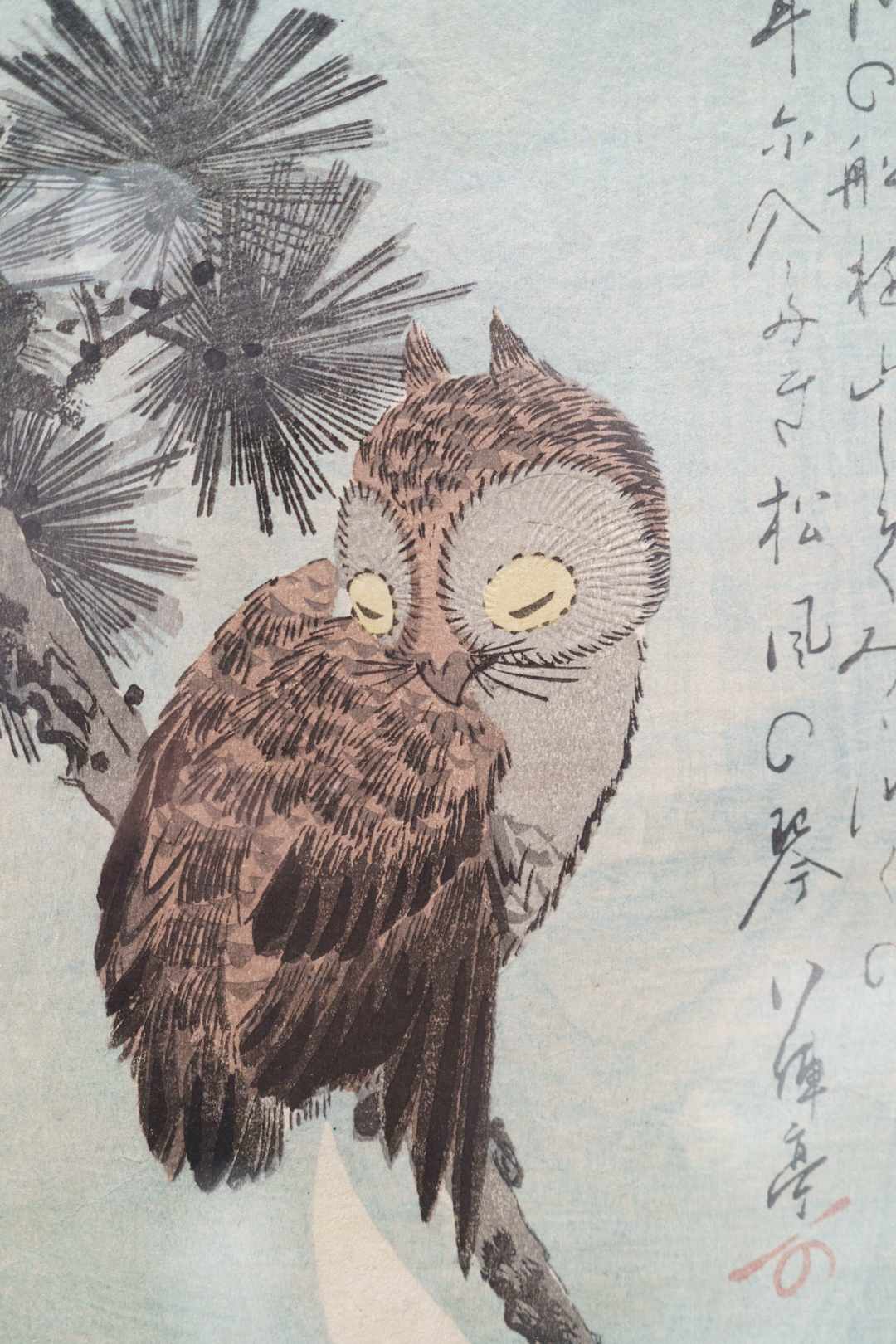

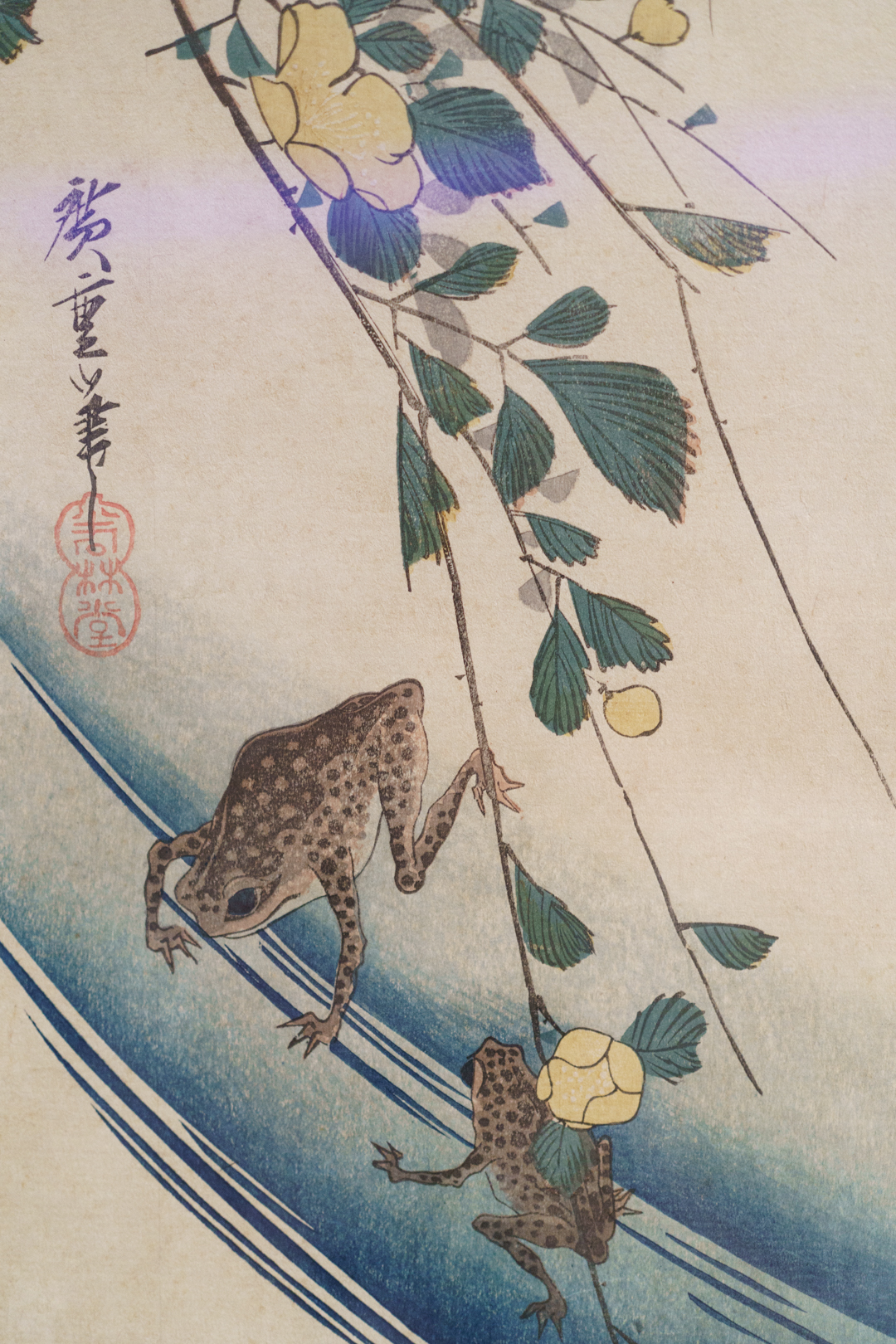

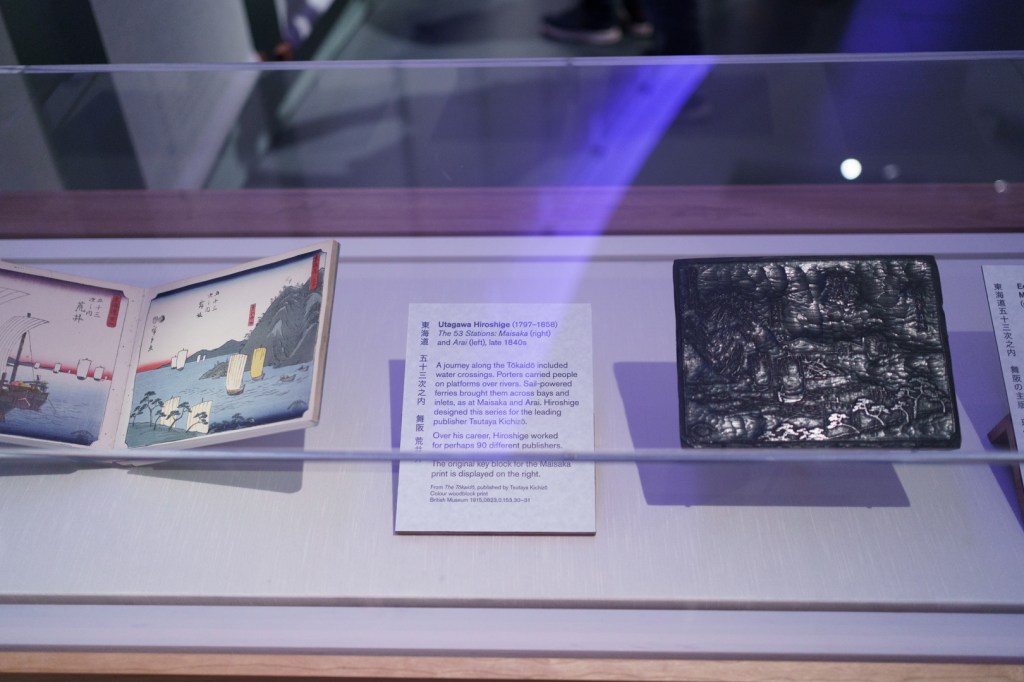

The exhibition gathers together all the different genres and categories of Hiroshige’s artistic production, many facilitated with loans from the renowned collection of American businessman Alan Medaugh. There are illustrated books, urban landscapes, prints of birds and flowers (kachō hanga), and of beauties (bijin-ga), rarely seen scroll paintings, and even an original key block (or outline block) for Maisaka from the Fifty-Three Stations.

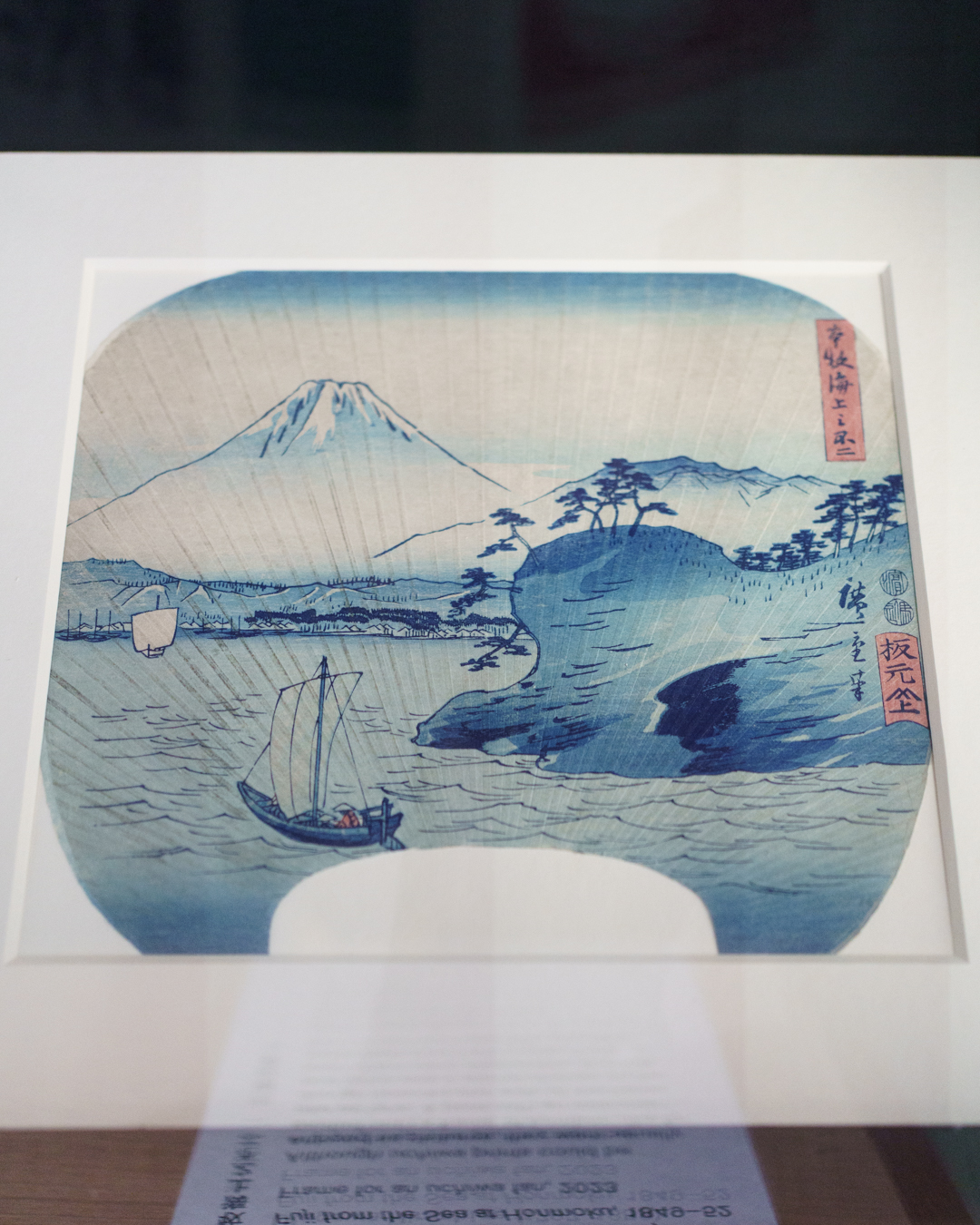

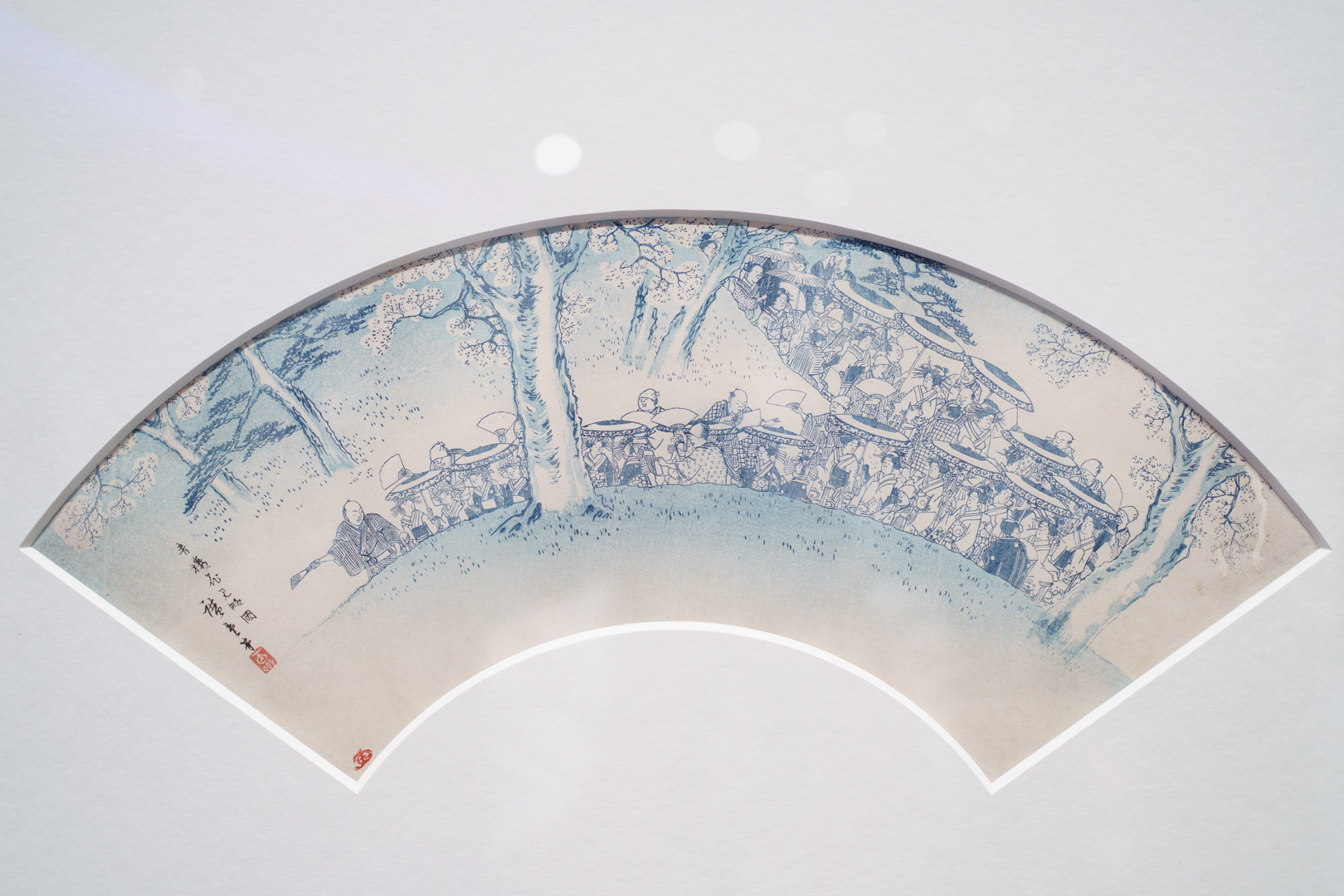

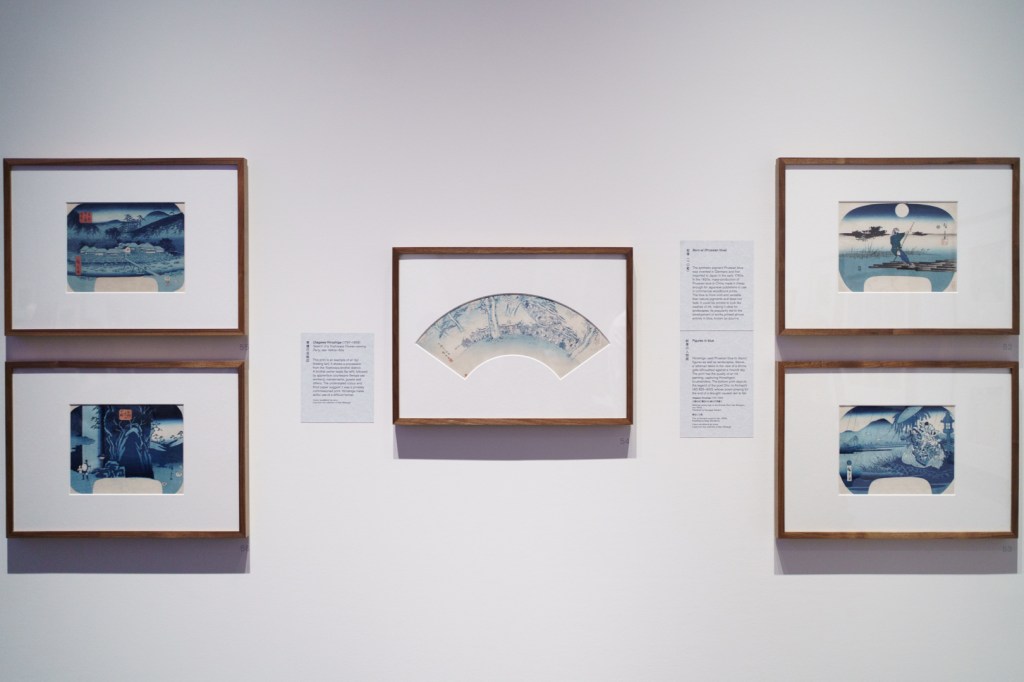

Actor prints are, unfortunately, heavily underrepresented, but this is easily forgiven in light of a major section on fan prints (uchiwa-e). Intended as ephemeral objects that were cut out and pasted onto the bamboo skeleton of rigid fans, the survival rate of such prints is extremely small, especially uncut impressions. The V&A actually has the largest collection of Hiroshige fan prints in the world, so I was surprised to find zero loans from them.

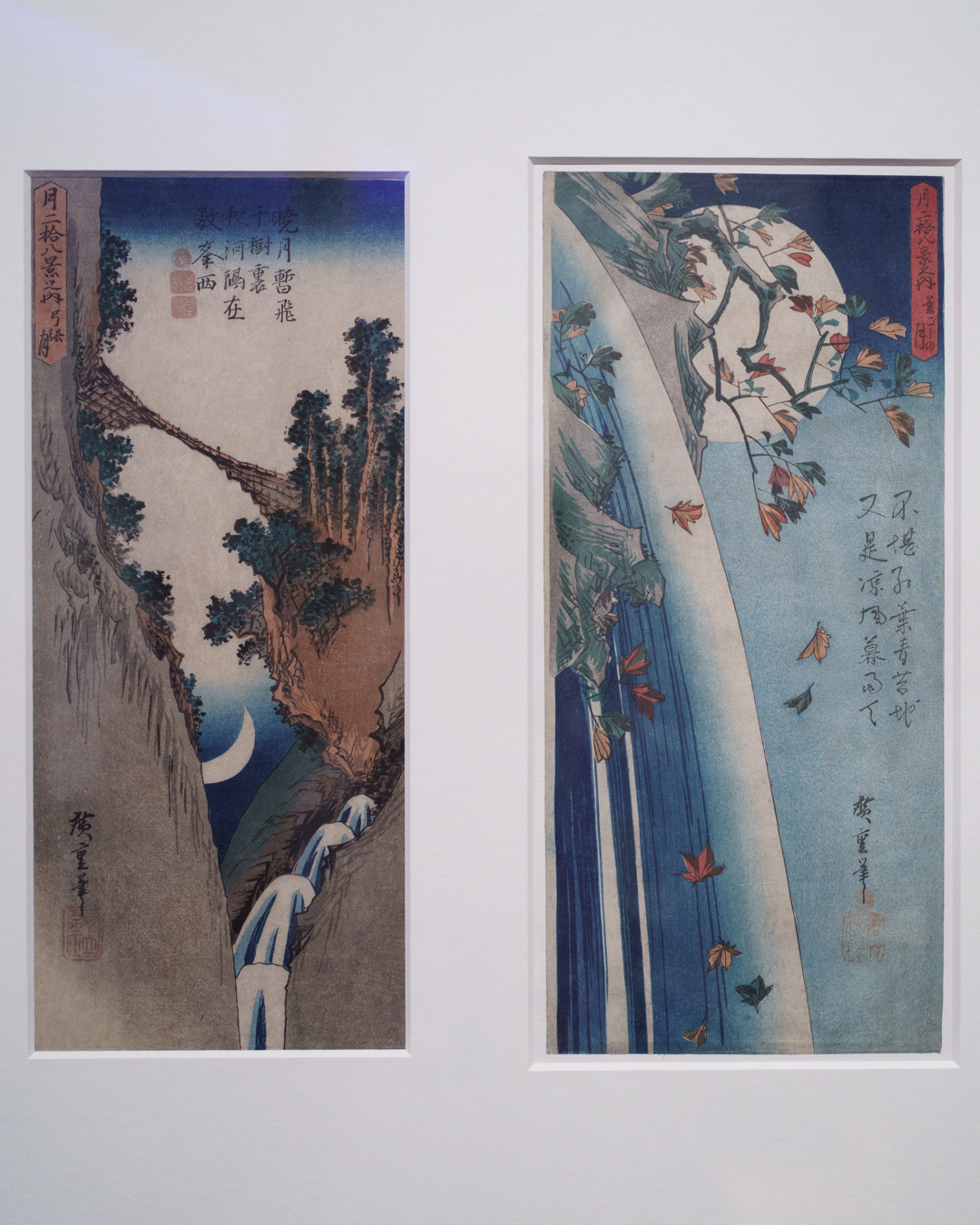

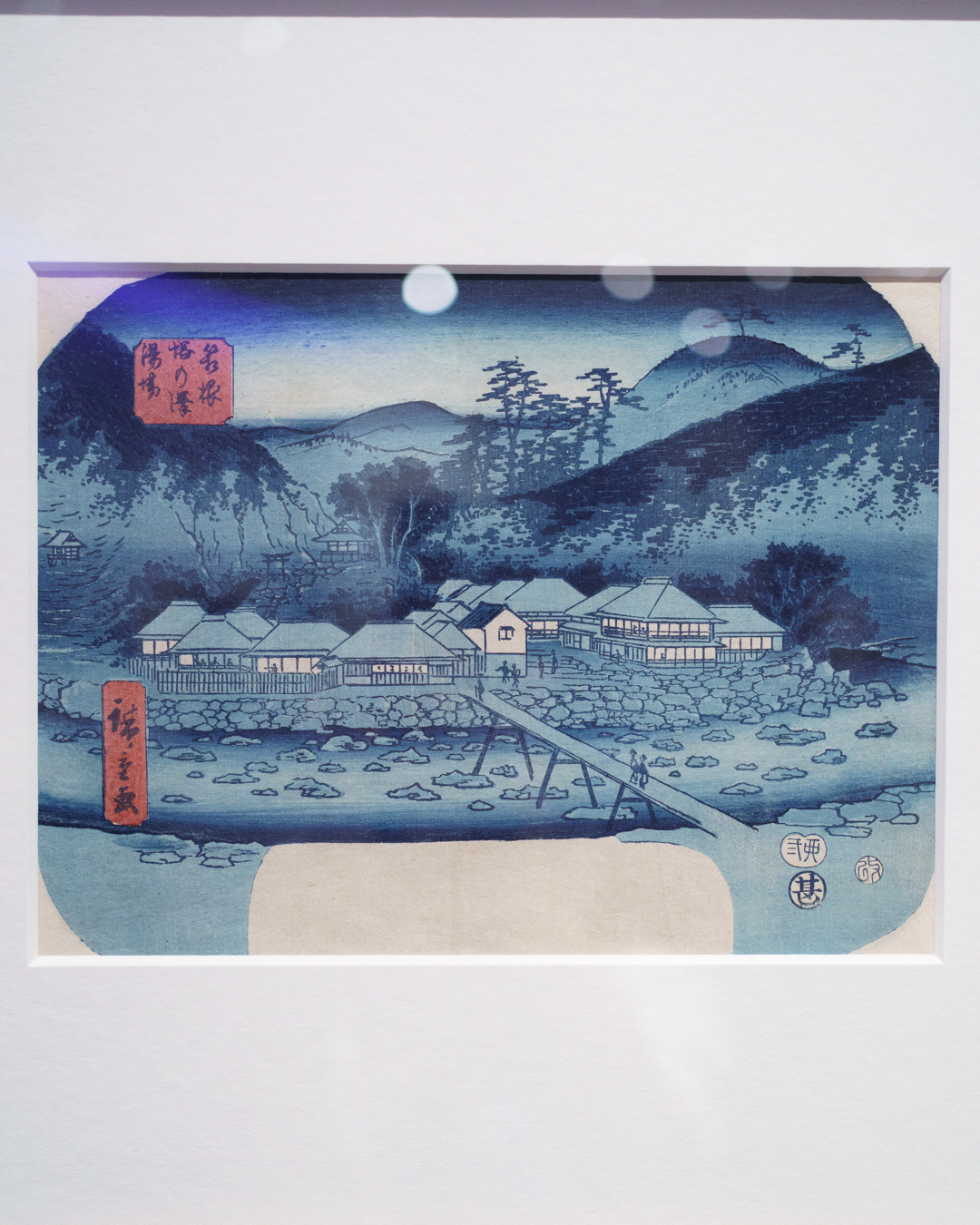

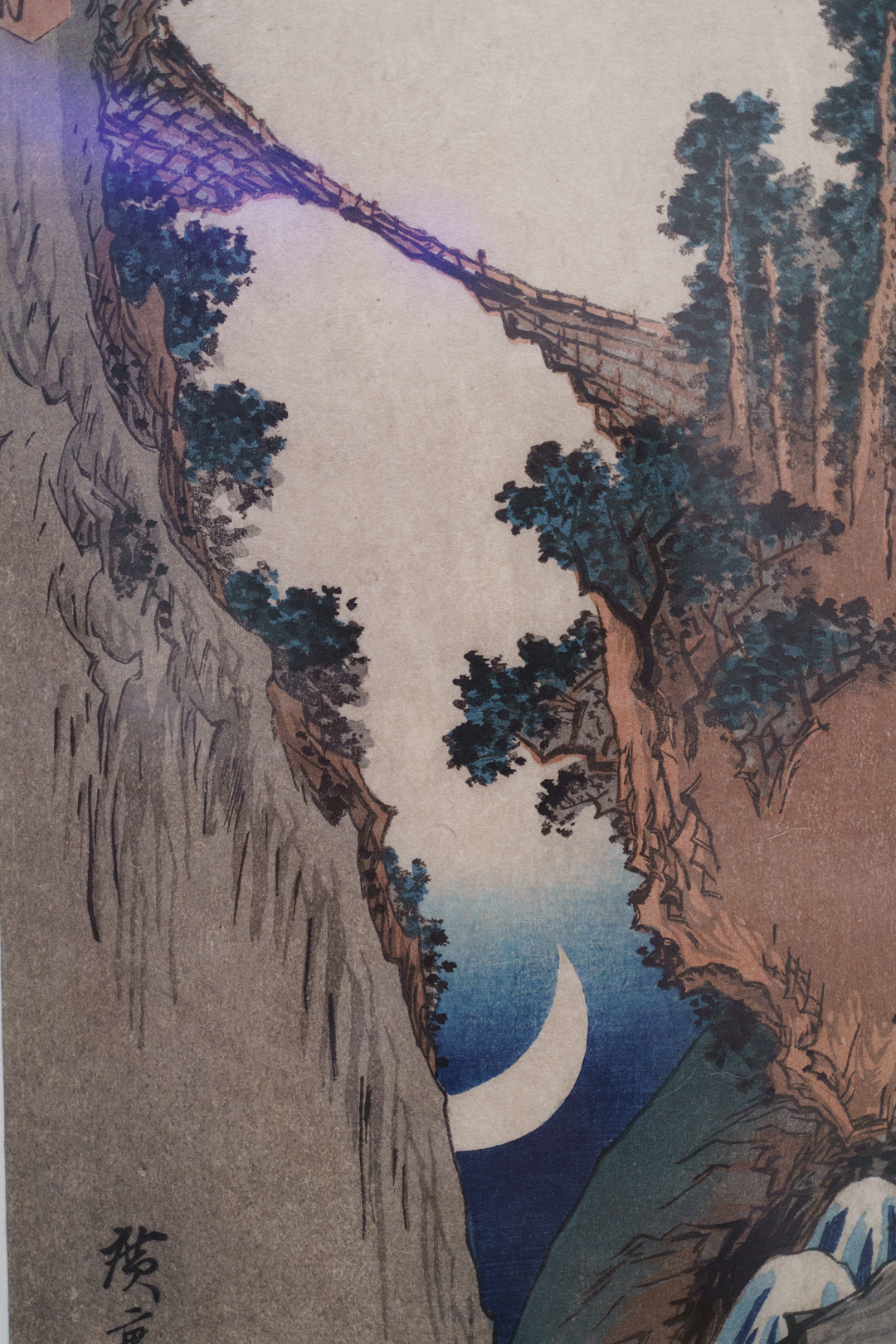

Nonetheless, this is a great opportunity to see a substantial and varied gathering of Japanese fan prints, including several highly sought after aizuri-e printed exclusively with Prussian blue, a pigment whose vibrancy quickly captured the hearts of ukiyo-e artists and their consumers.

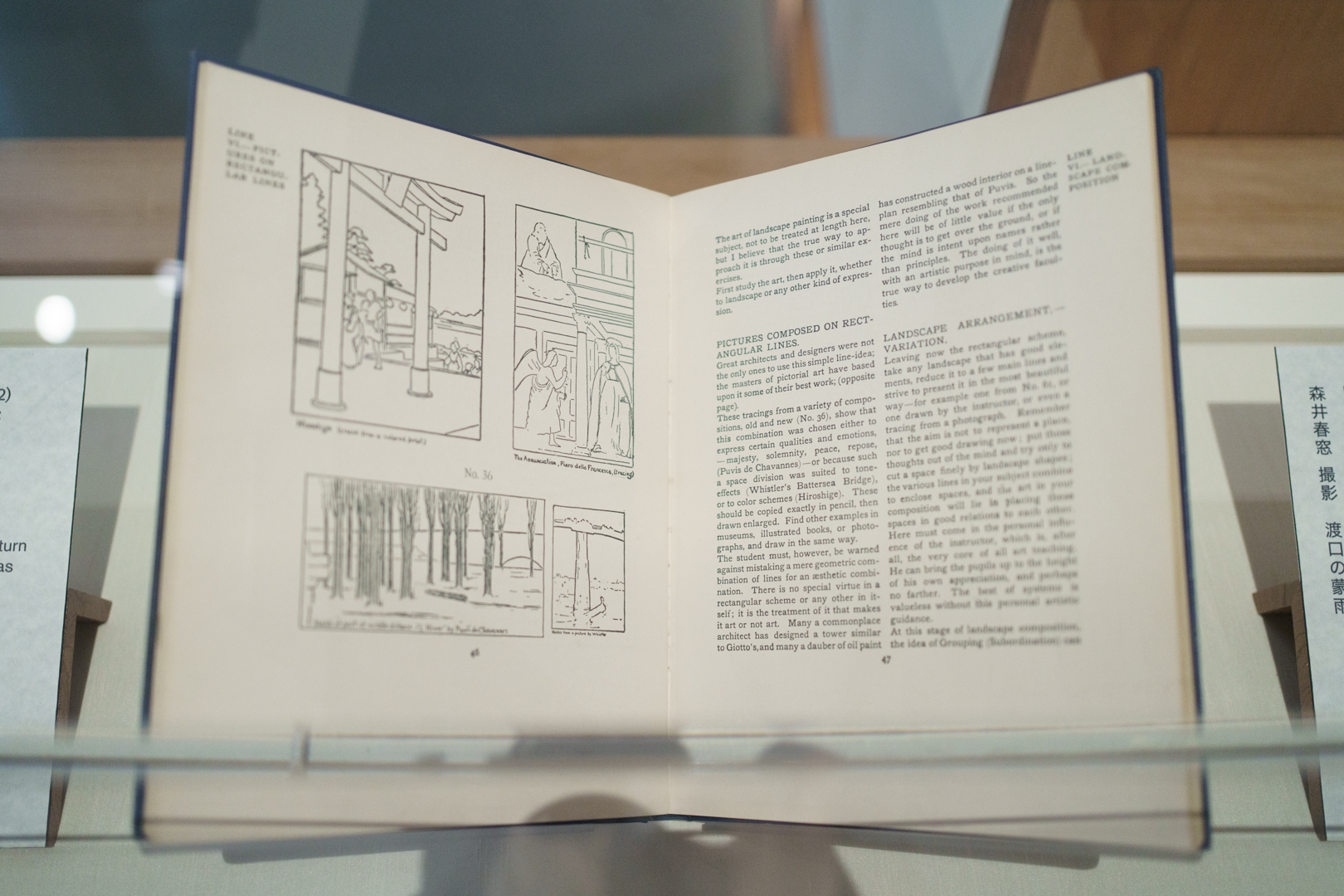

Alongside comparisons with illustrated books and other visual sources, a selection of videos educate visitors on Hiroshige’s creative and working processes, and on the ukiyo-e collaborative system between artist, block cutter, printer, and publisher. This was later replaced in the early 20th century by the sōsaku-hanga movement, which encouraged the artist to assume all roles (the equivalent of a European peintre-graveur).

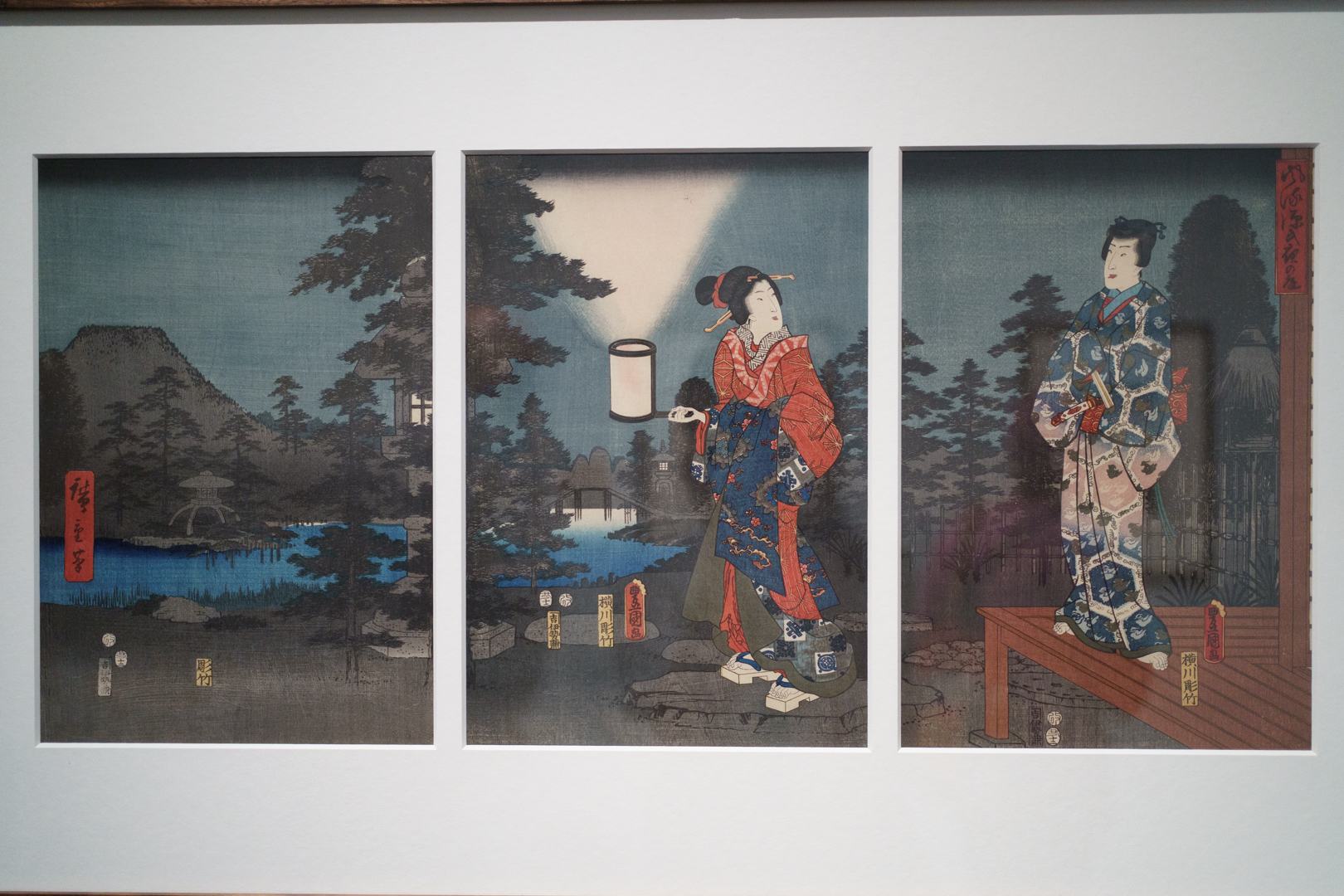

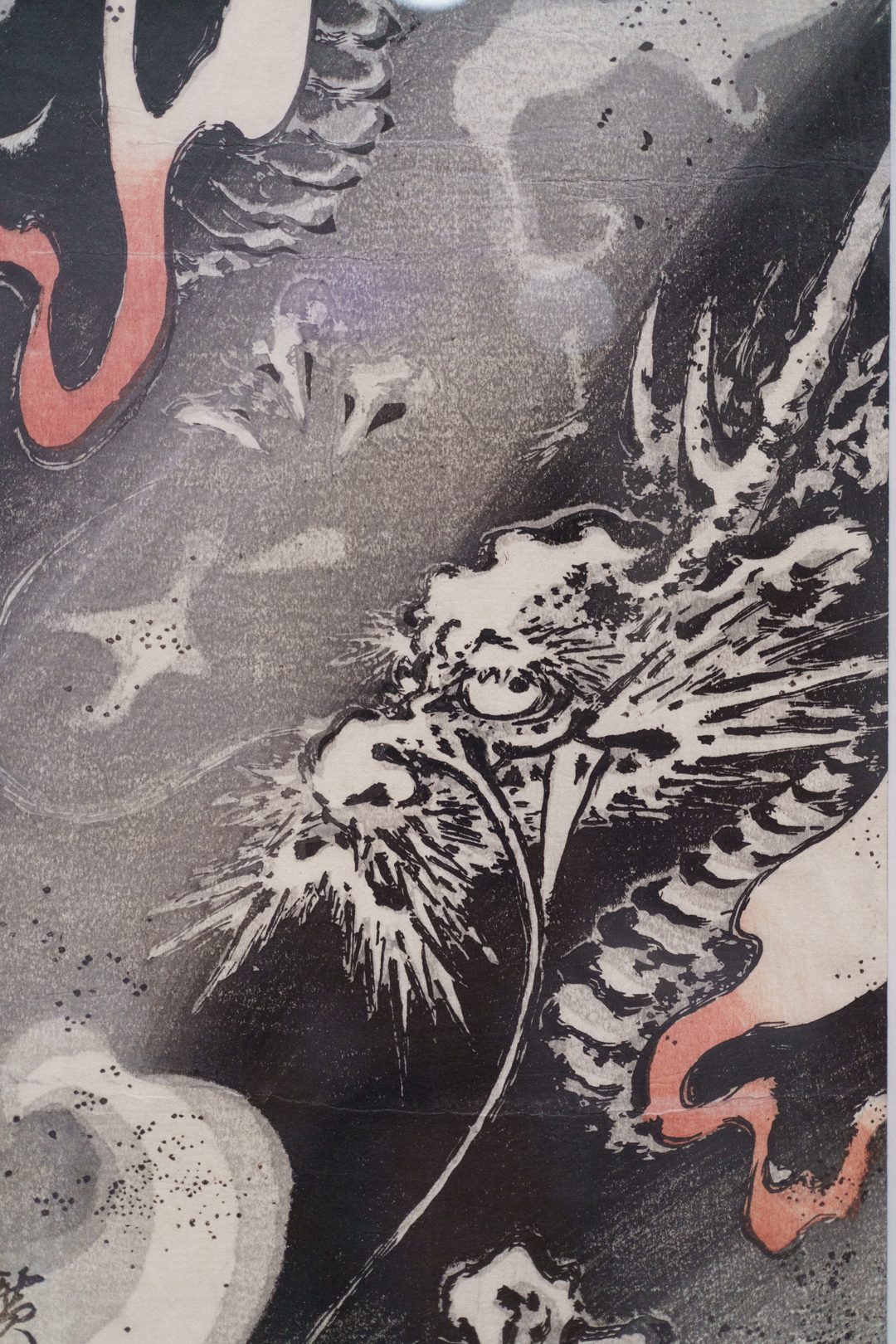

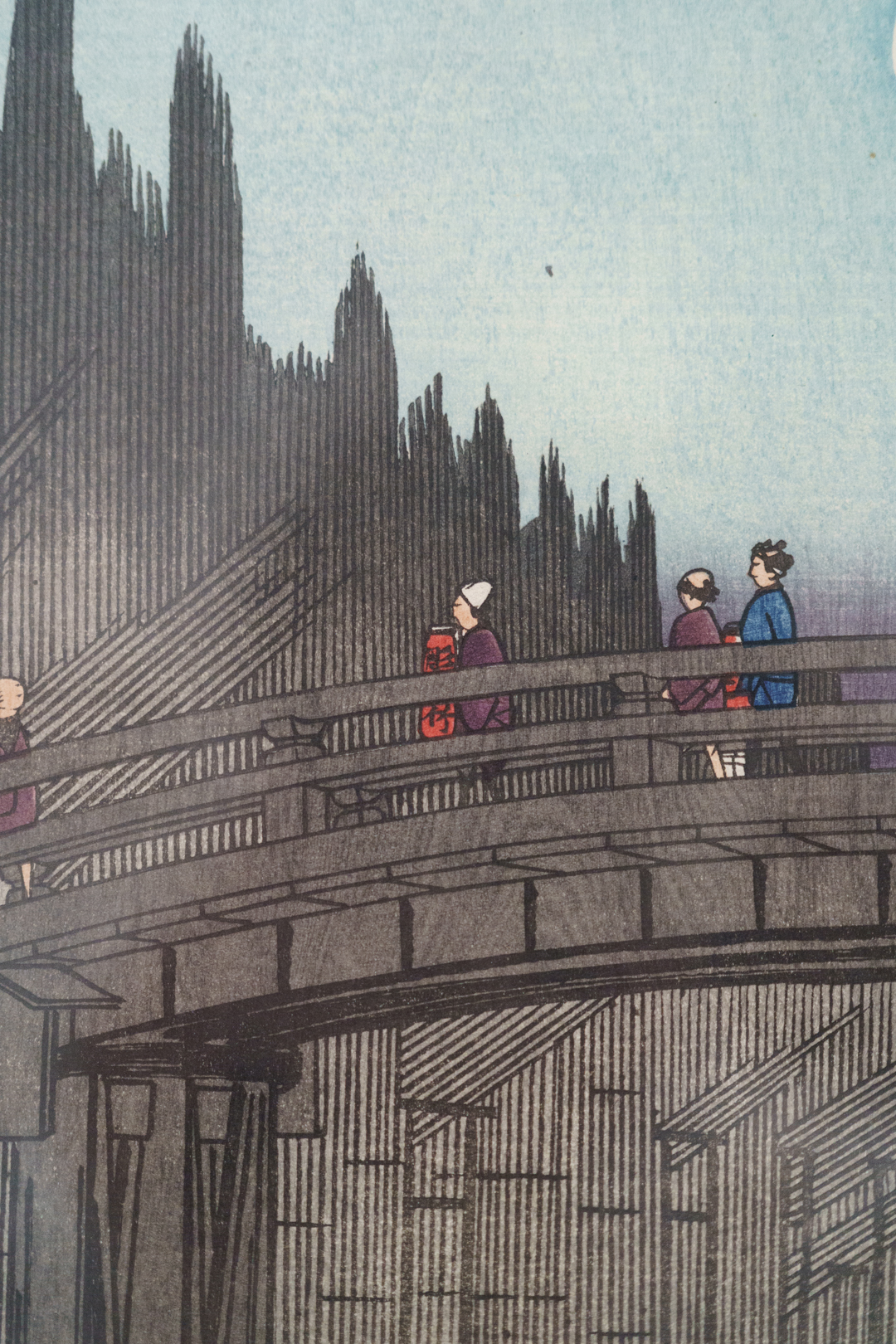

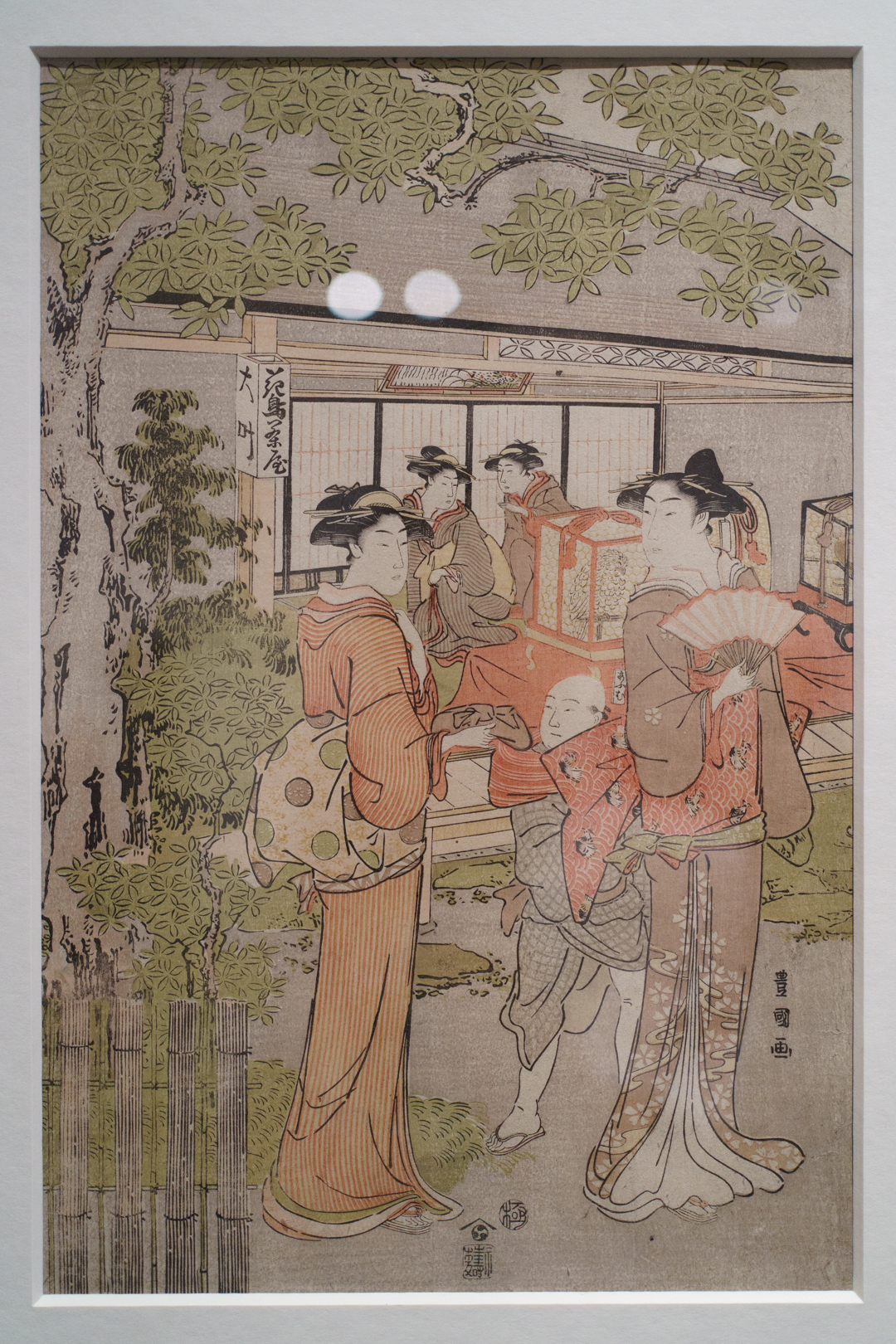

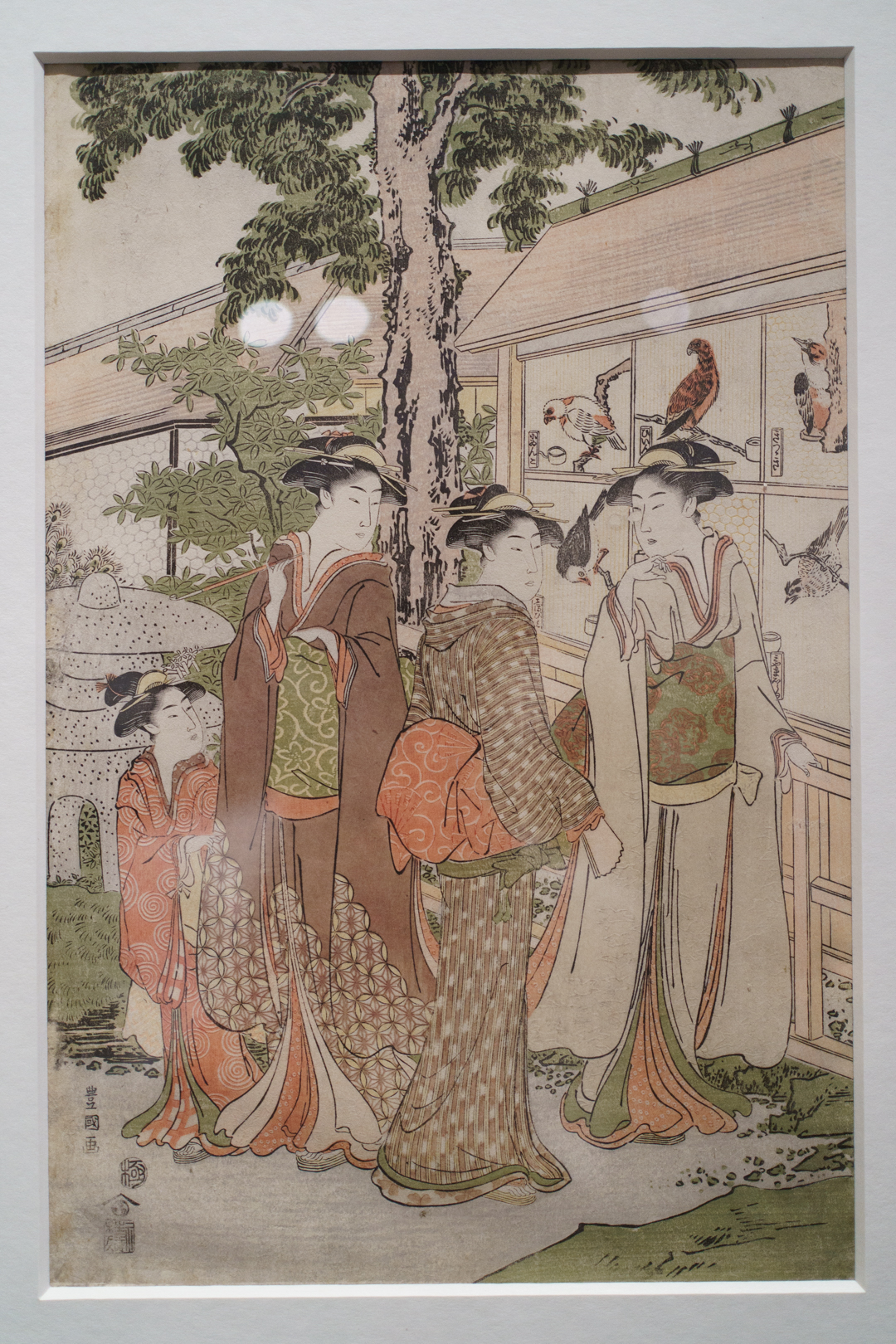

Throughout the show, we also find Hiroshige collaborating with other artists, not just publishers, such as Keisai Eisen and Utagawa Kunisada. One example is Garden at Night, in which Kunisada contributed to the figures while Hiroshige did the landscapes; here, the collaboration was dictated by the strengths of each artist.

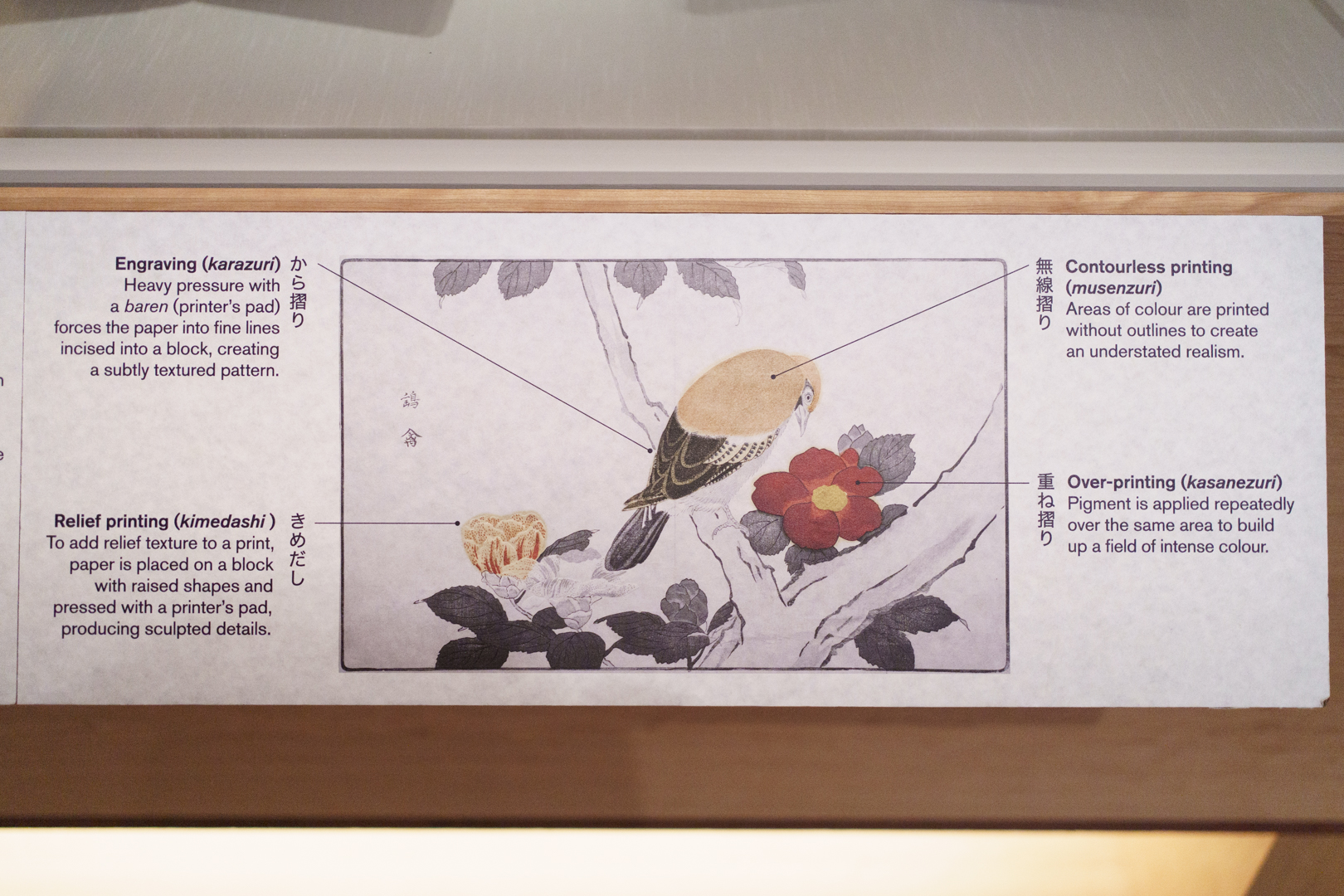

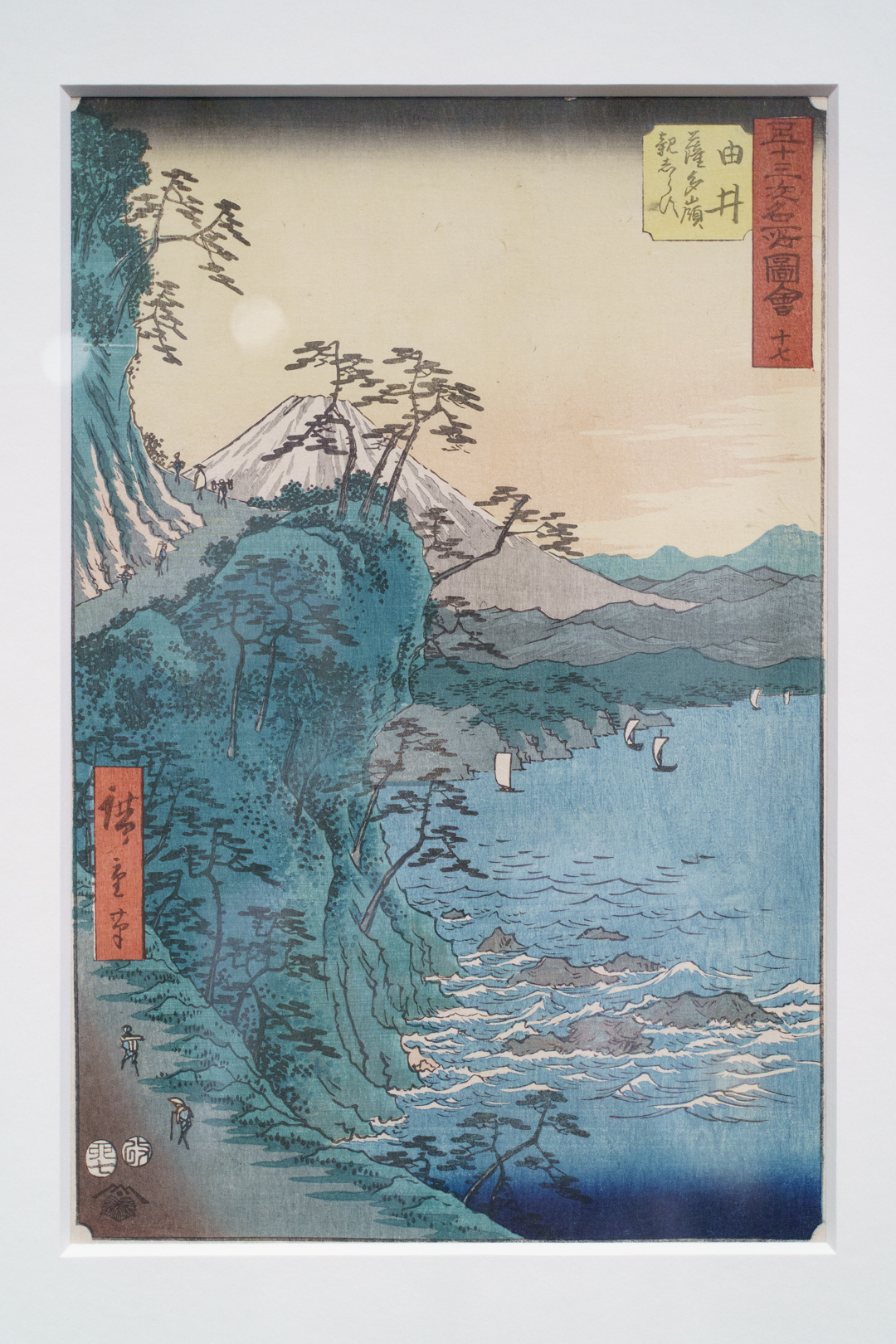

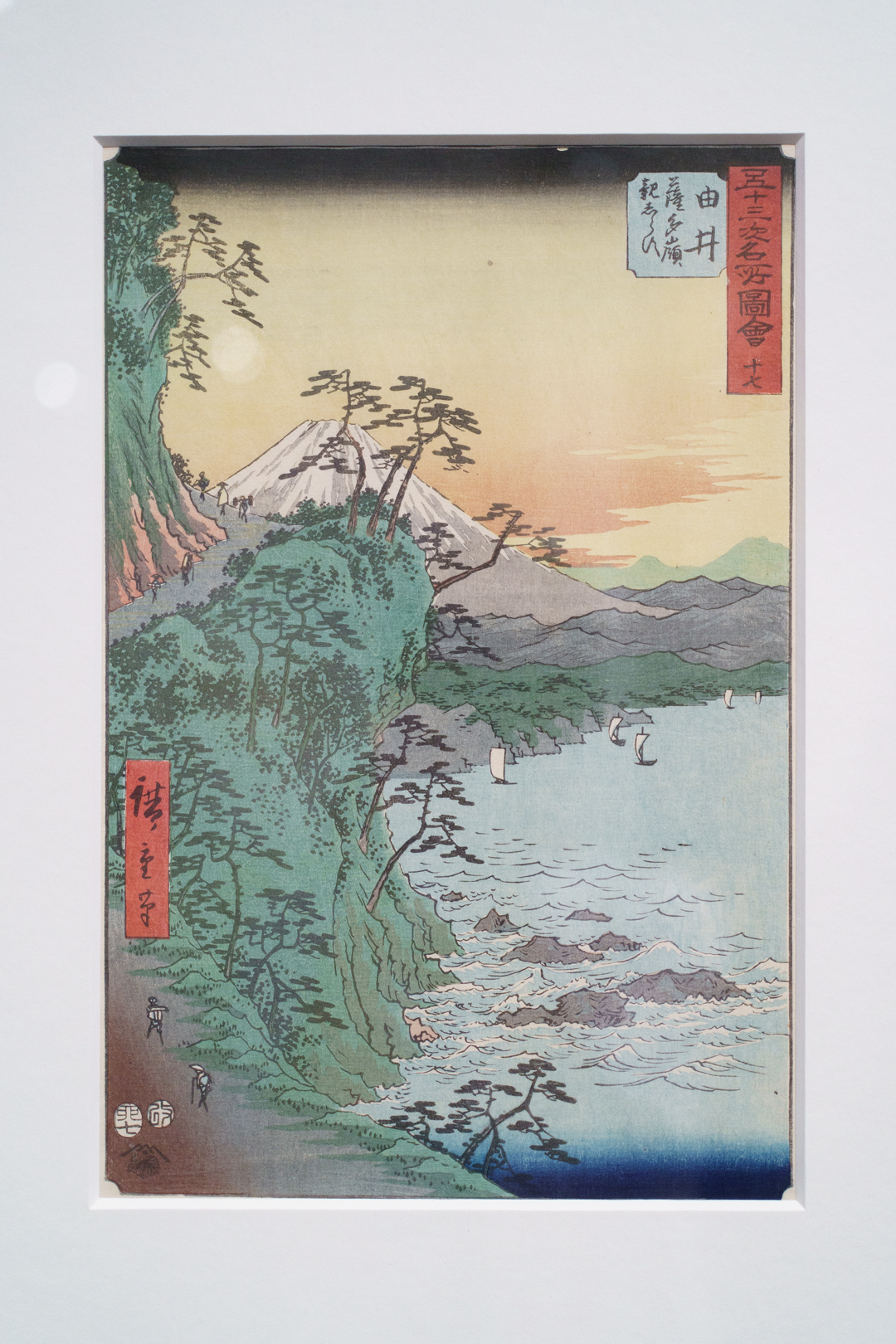

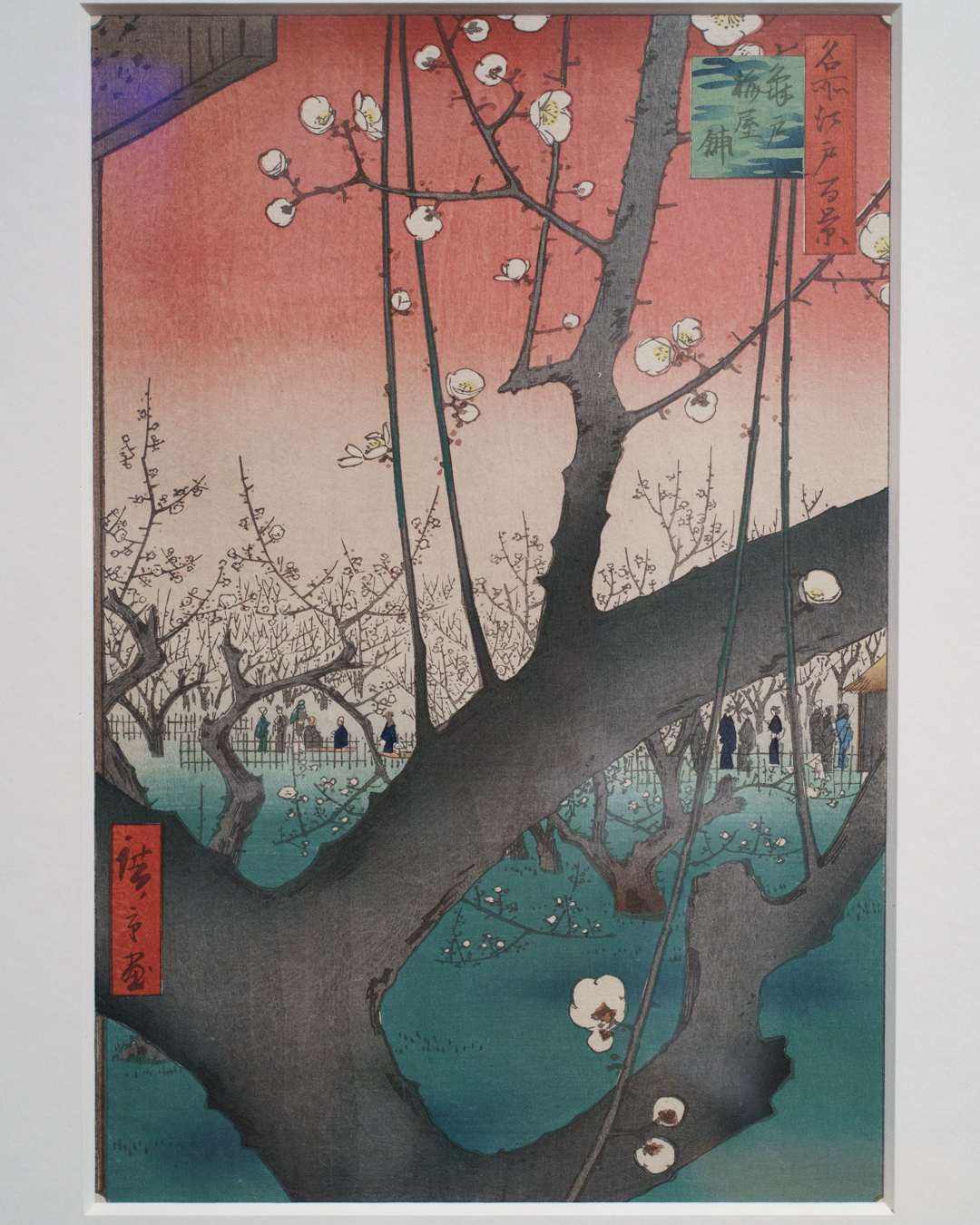

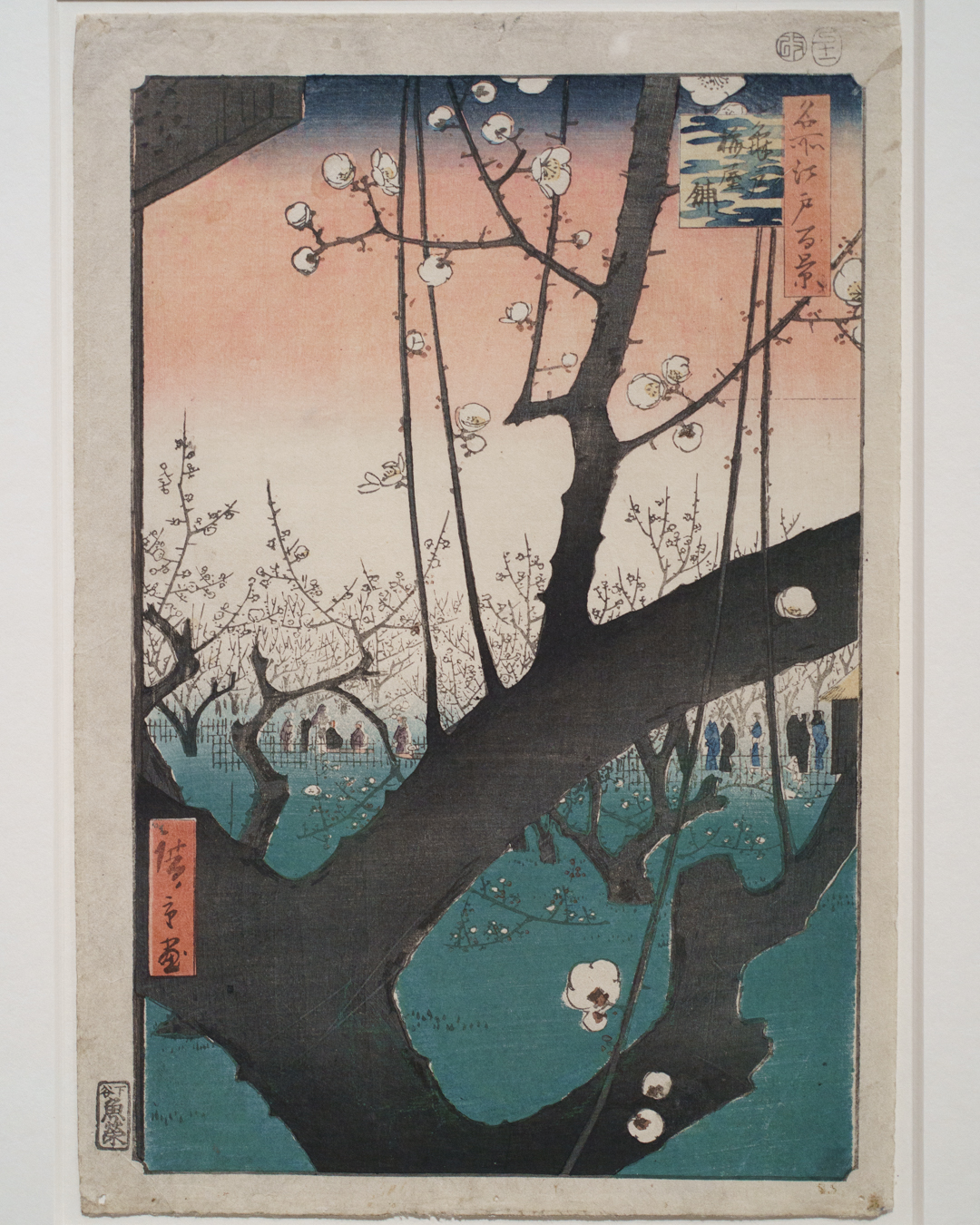

I was incredibly grateful to find captions identifying specific print techniques used in his prints – engraving (karazuri), relief printing (kimedashi), contourless printing (musenzuri), and over-printing (kasanezuri) – thereby encouraging visitors to look more closely at the material qualities of each print. Throughout the show, there is an emphasis on early and later printings of certain prints, emphasising their popularity and large production output – sometimes up to 15,000 impressions before the block wore down – as well as variations in colour, pressure, and mood.

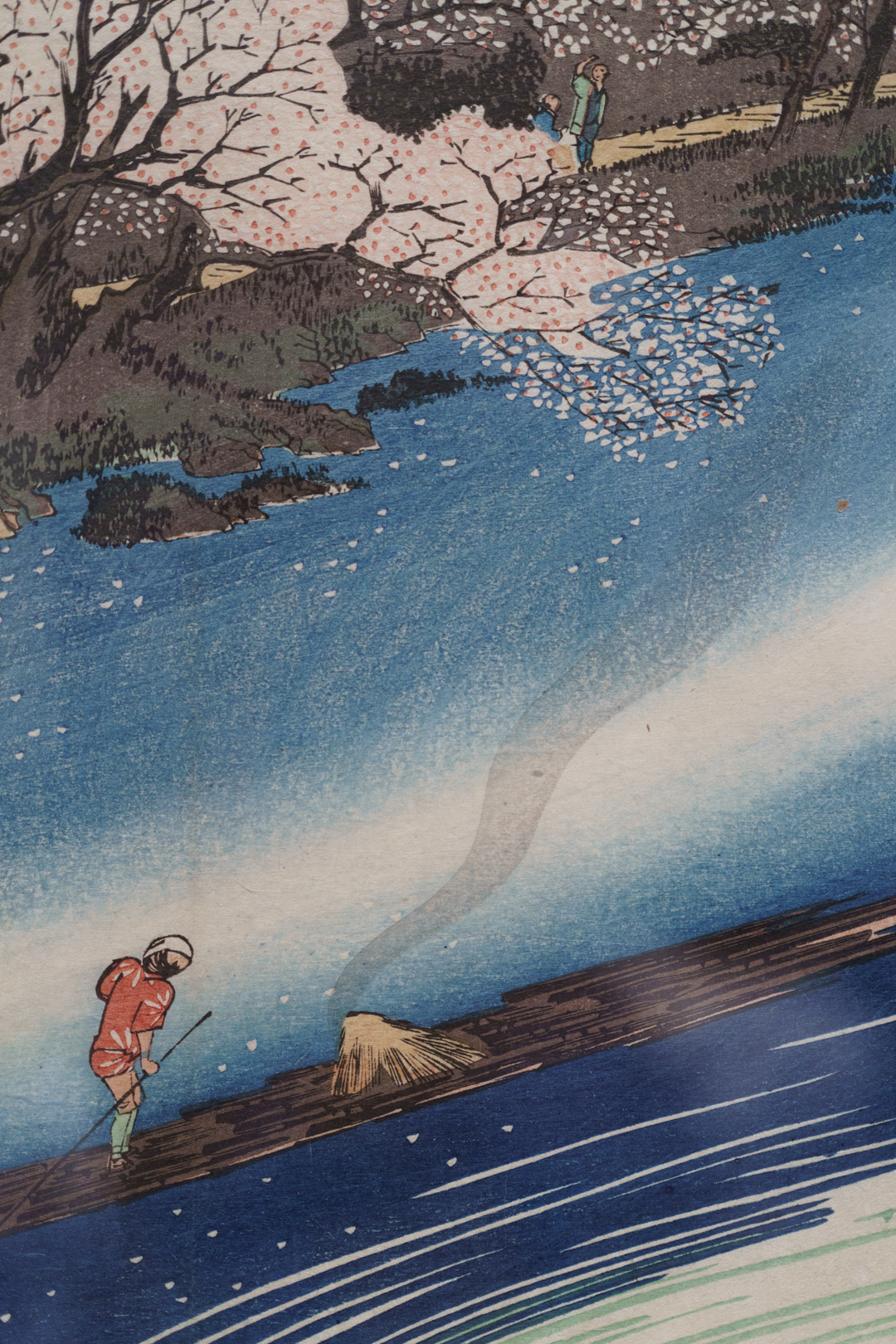

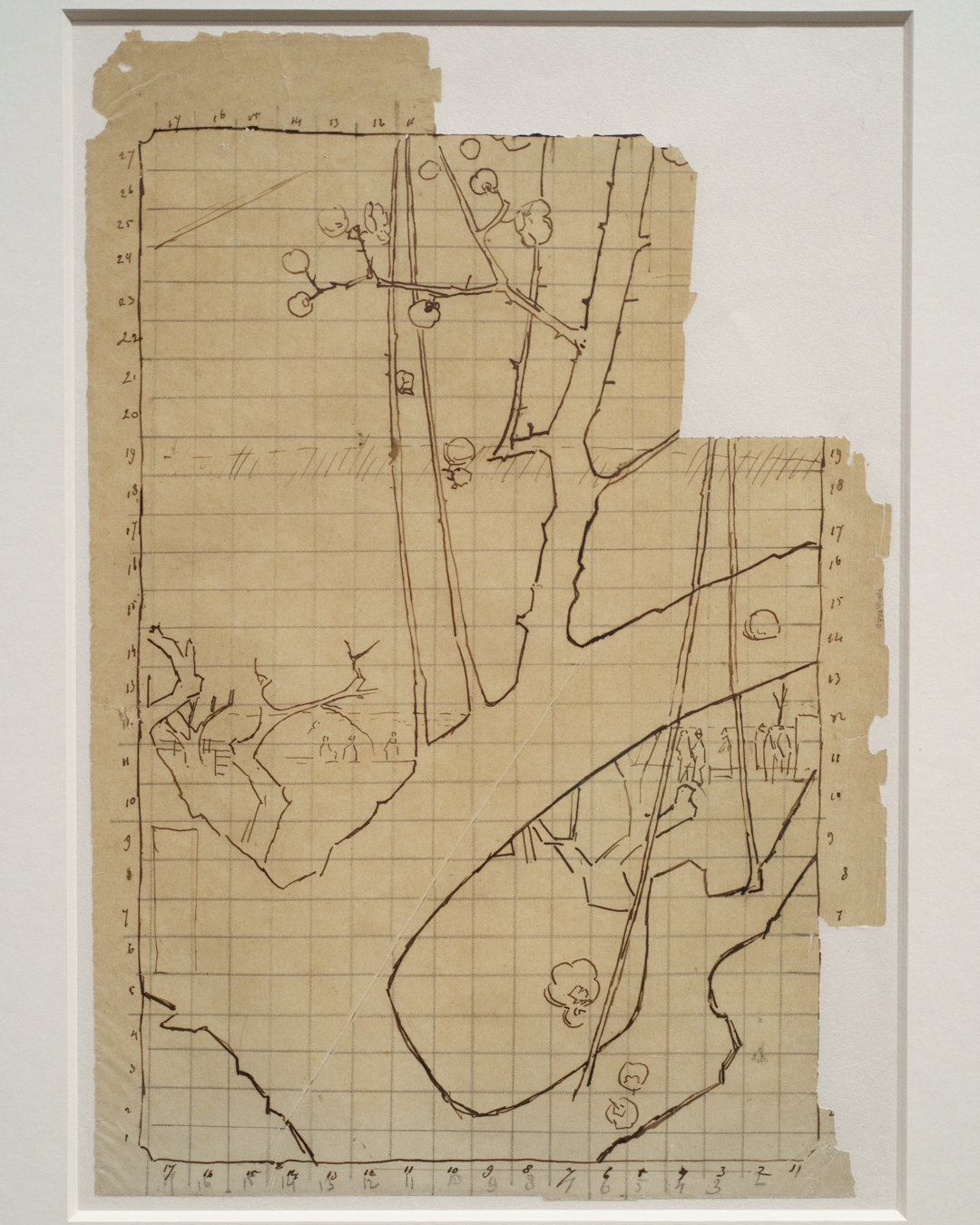

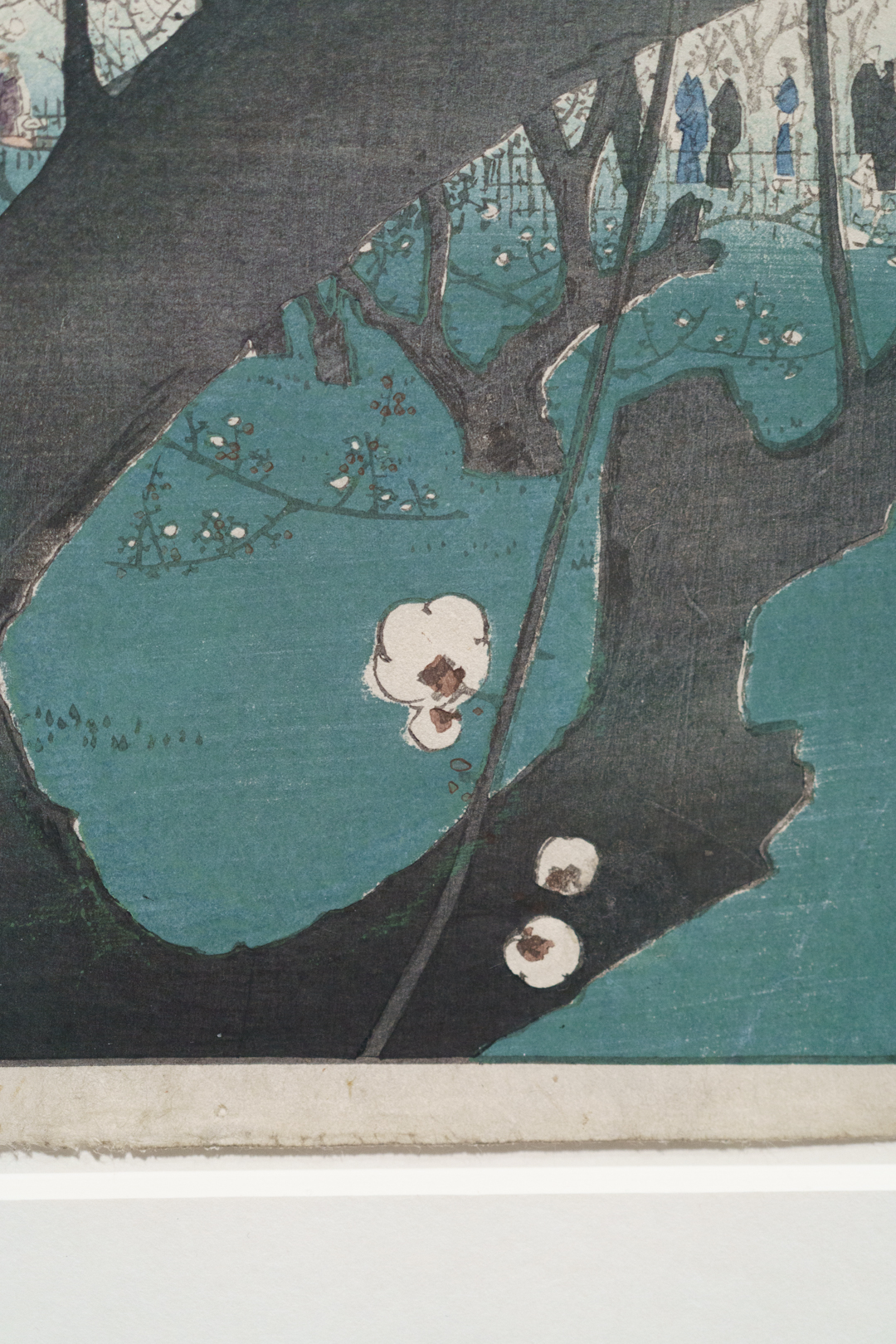

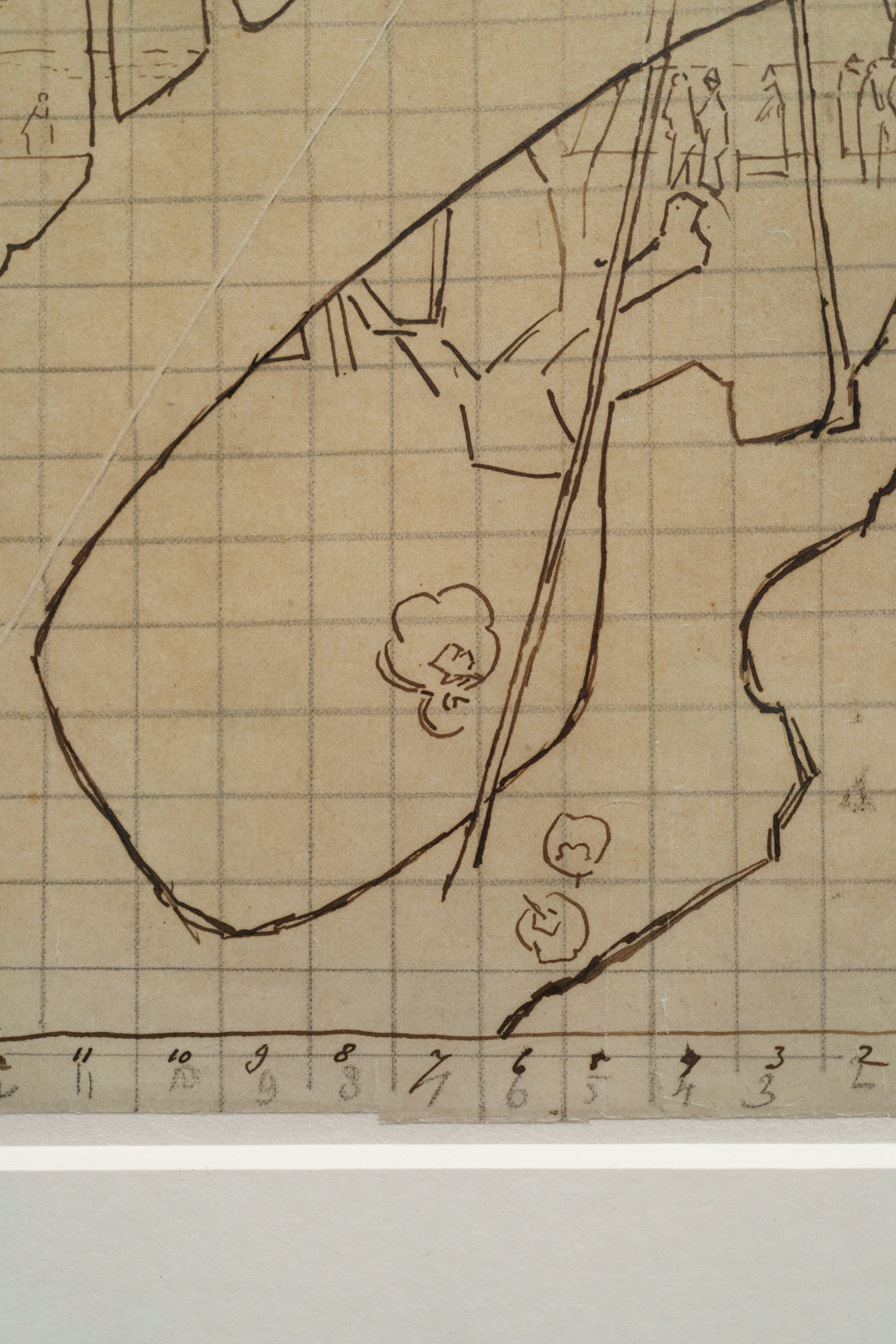

One such example is The Plum Garden at Kameido, here represented by a vibrant impression from the first edition and Vincent van Gogh’s personal copy of a later edition. Completing the selection is van Gogh’s tracing of the print; you can tell it is from the later edition based on the traced lines denoting areas where the printer misaligned parts of the image, notably the cherry blossoms. Unfortunately, the painted copy that van Gogh would go on to produce is not part of the exhibition, which in fact reproduces the colours of a first edition version of Hiroshige’s print.

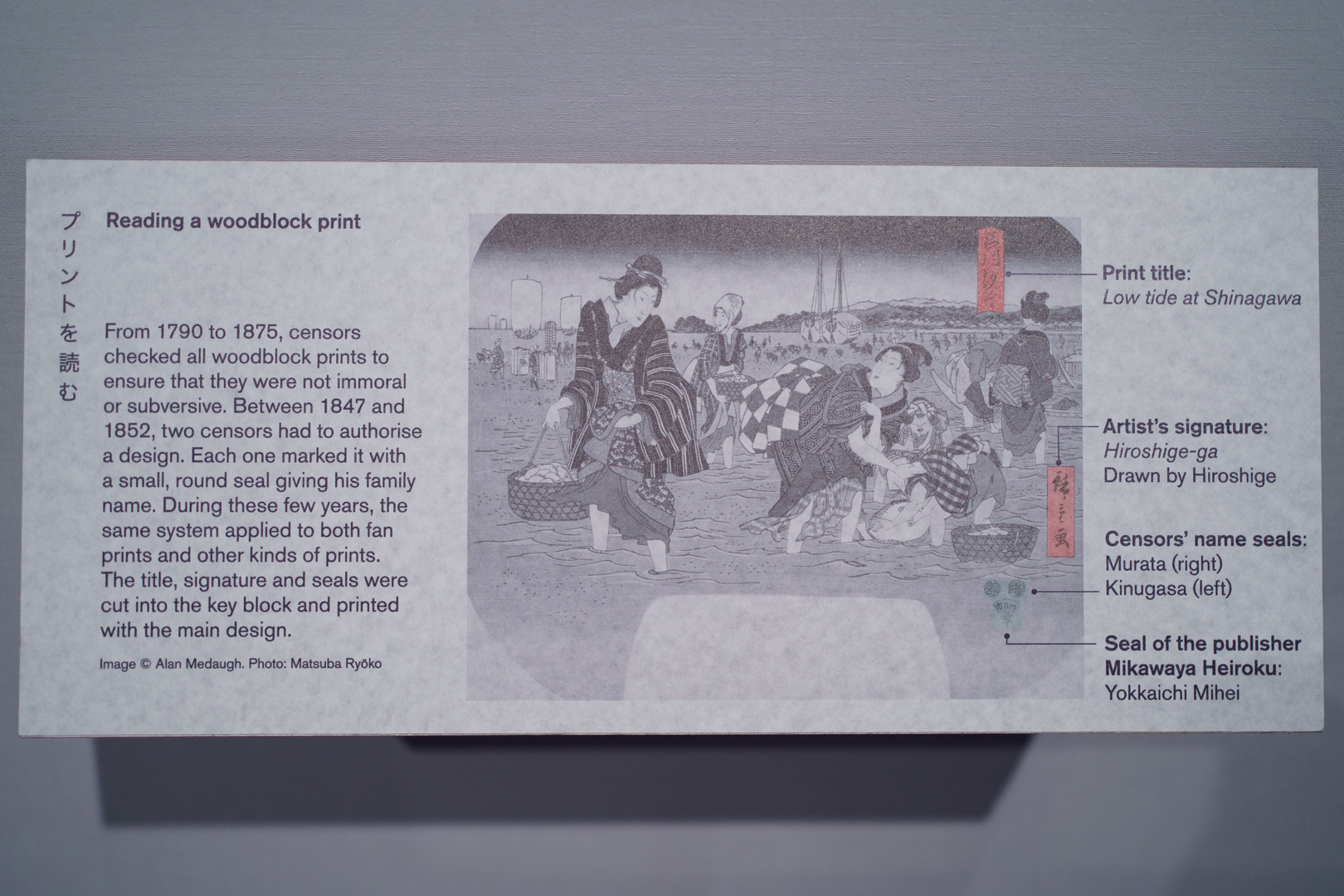

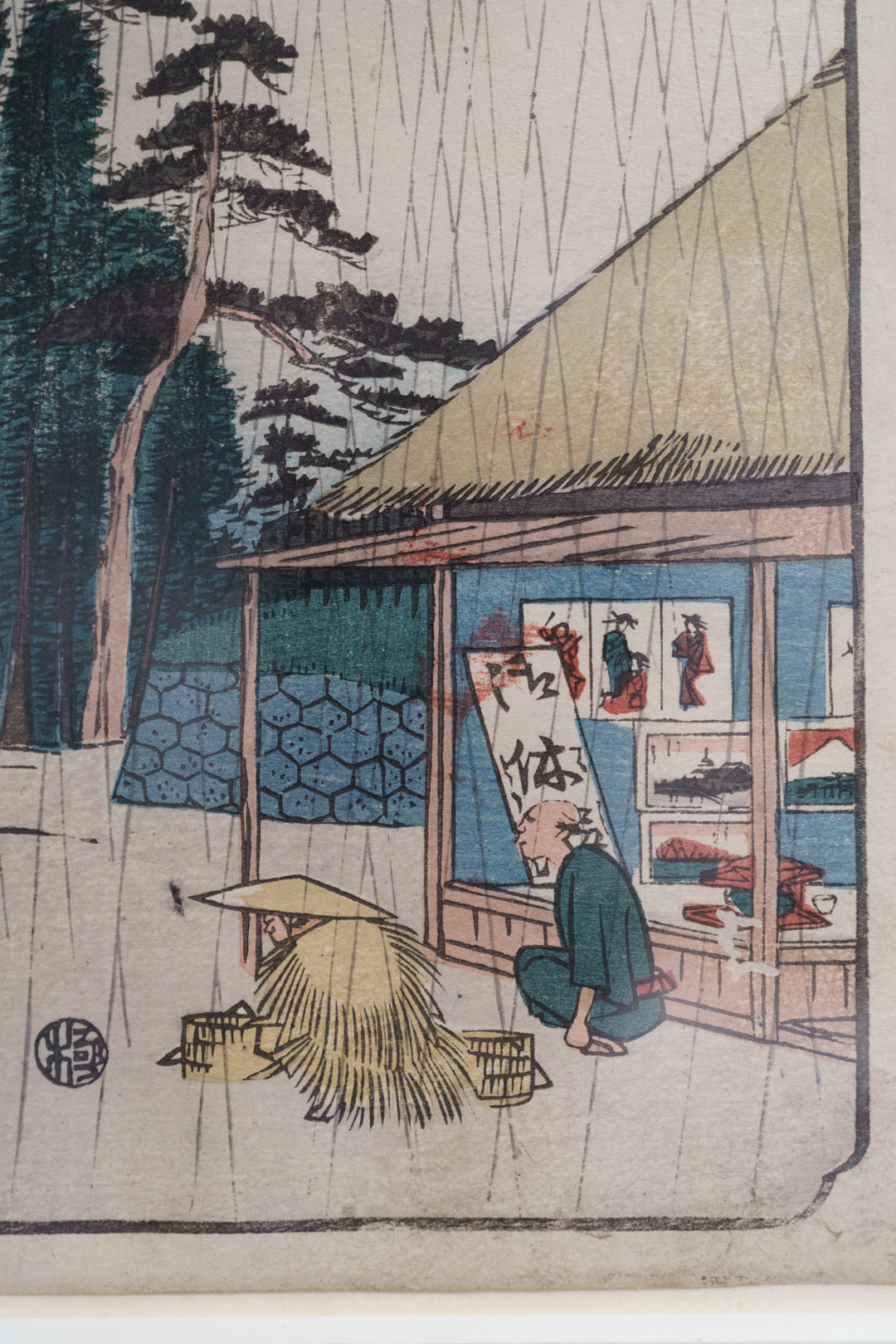

For one of the fan prints, a caption crucially educates us on how to read Japanese woodblock prints with its artist signatures, censor’s seals, and publisher’s marks, which opens up into the wider context of how prints were circulated and monitored. In some cases, prints depicted how prints were used in society, often pasted to the walls of homes and shops.

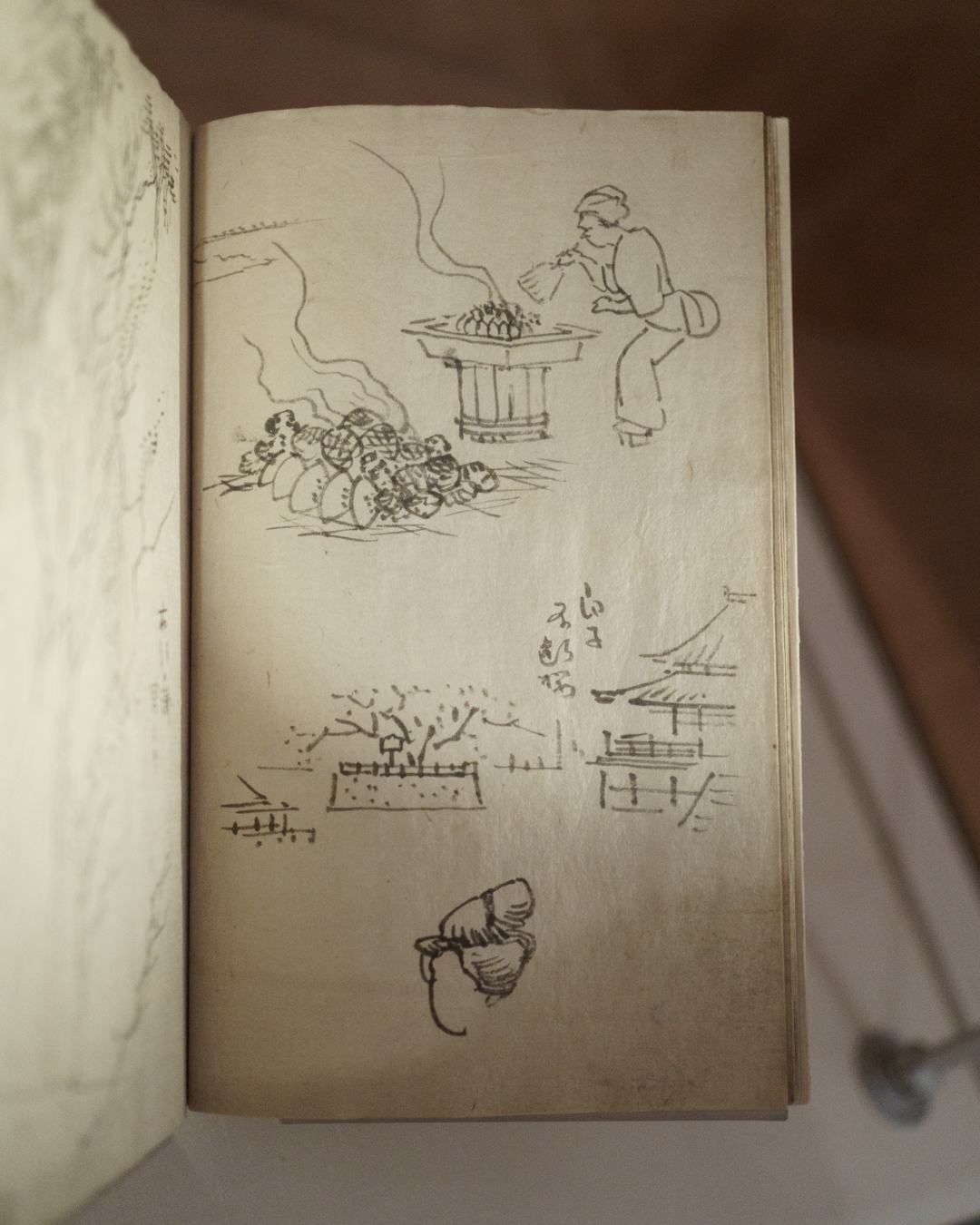

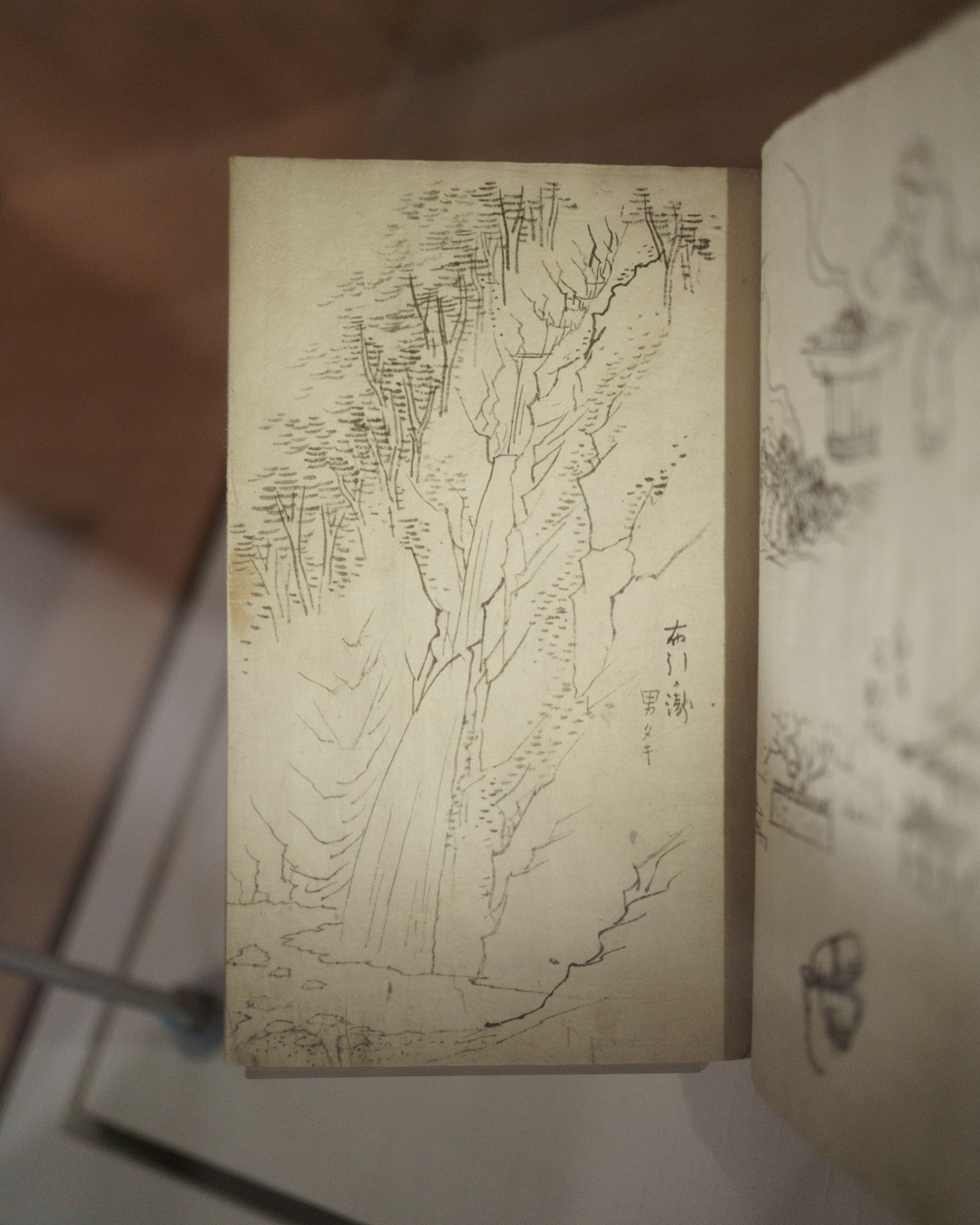

The concluding section on Hiroshige’s legacy is a little scattered. It briefly introduces his students Hiroshige II and Hiroshige III – the master’s artist name was inherited through the workshop – and how the elder artist’s sketchbooks were passed down and used as visual sources, before quickly listing off numerous artists who were inspired by his works and have created artistic dialogues.

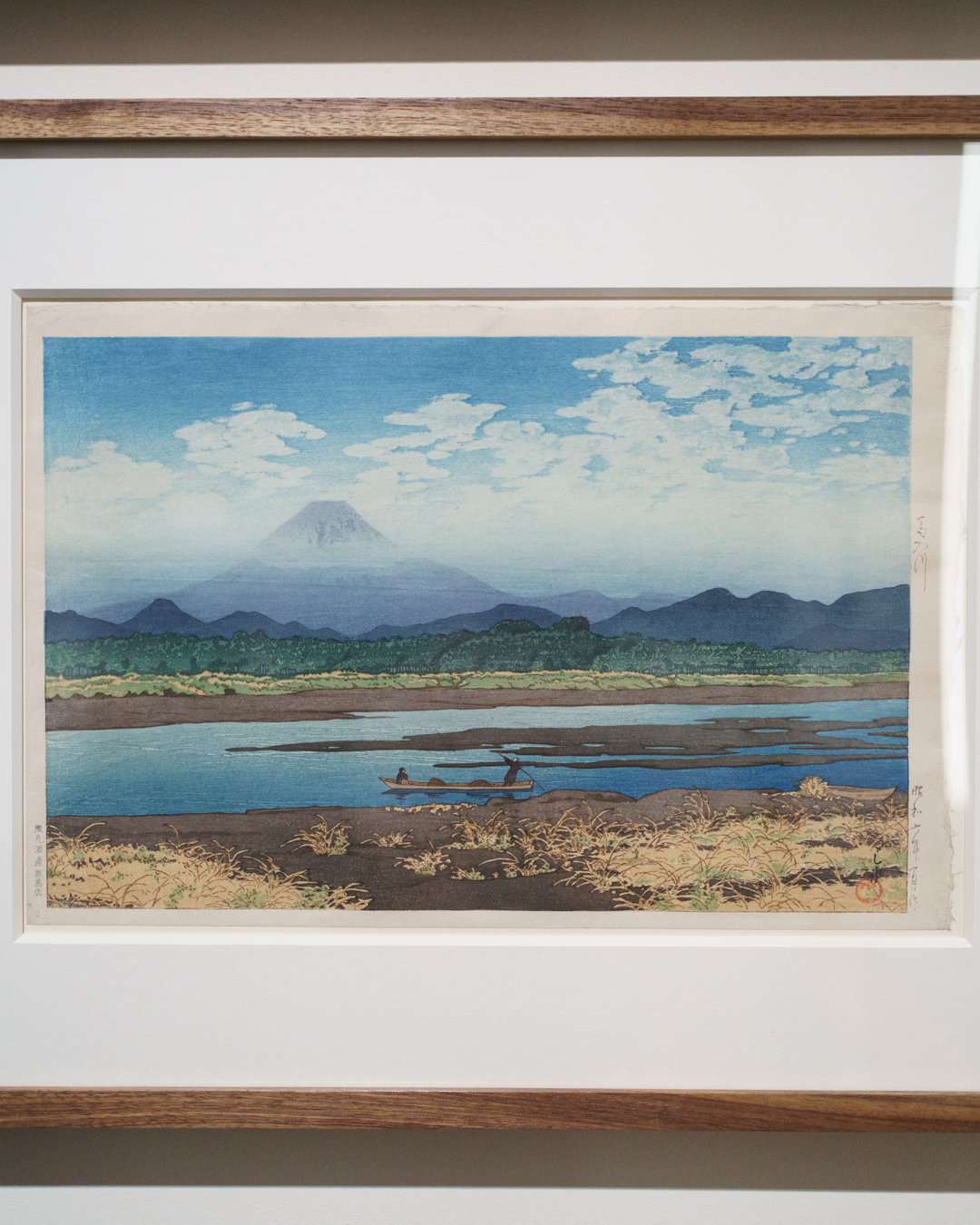

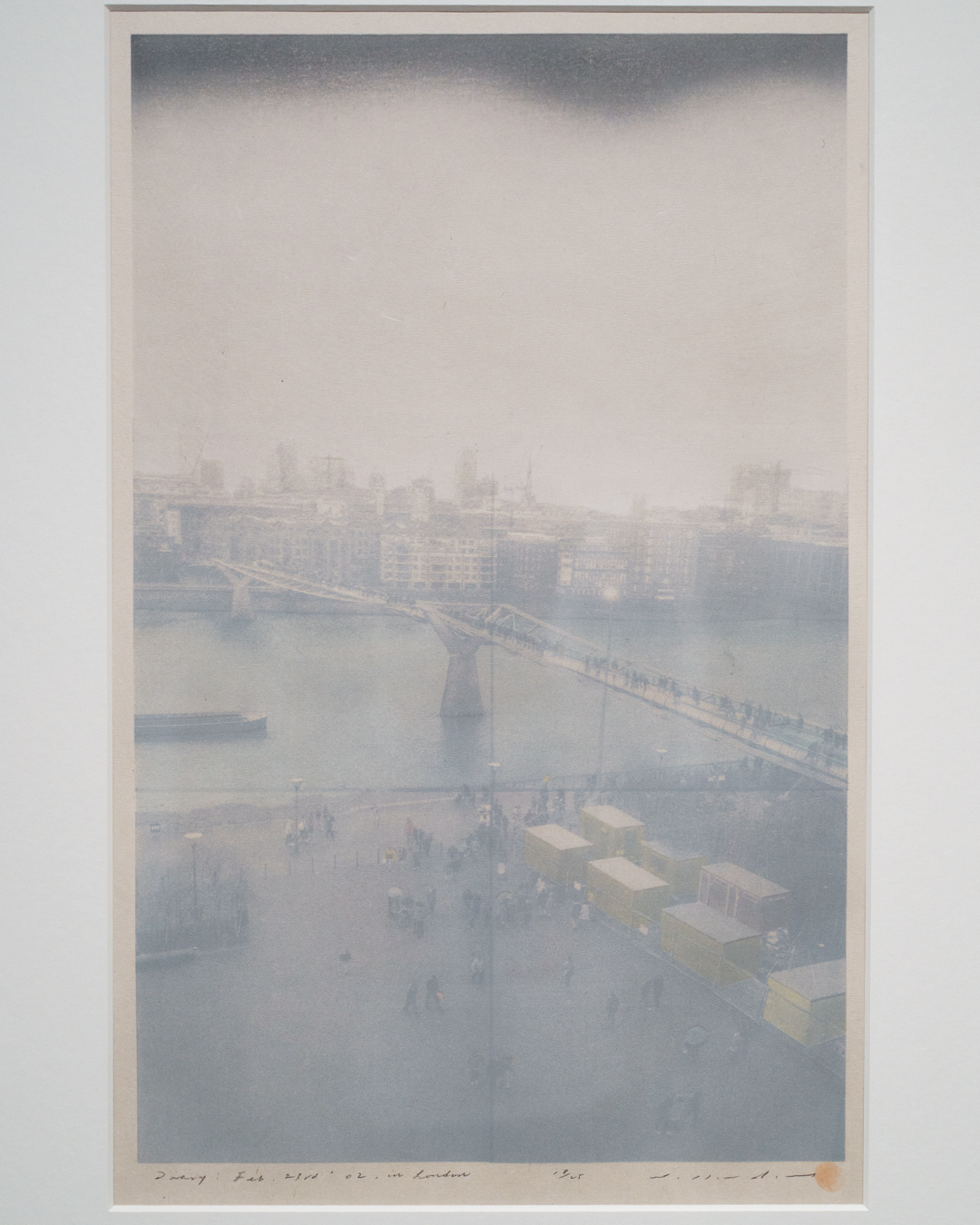

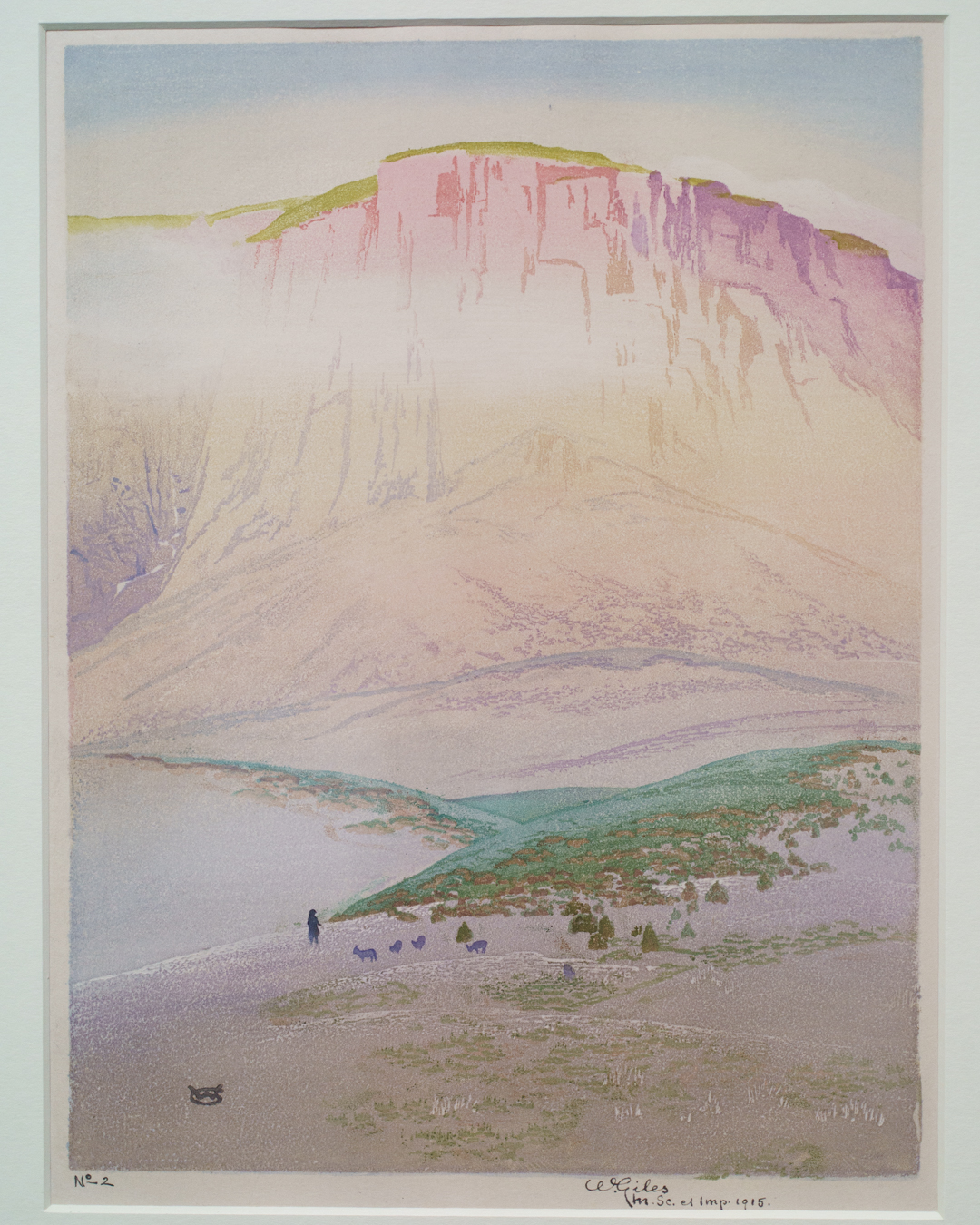

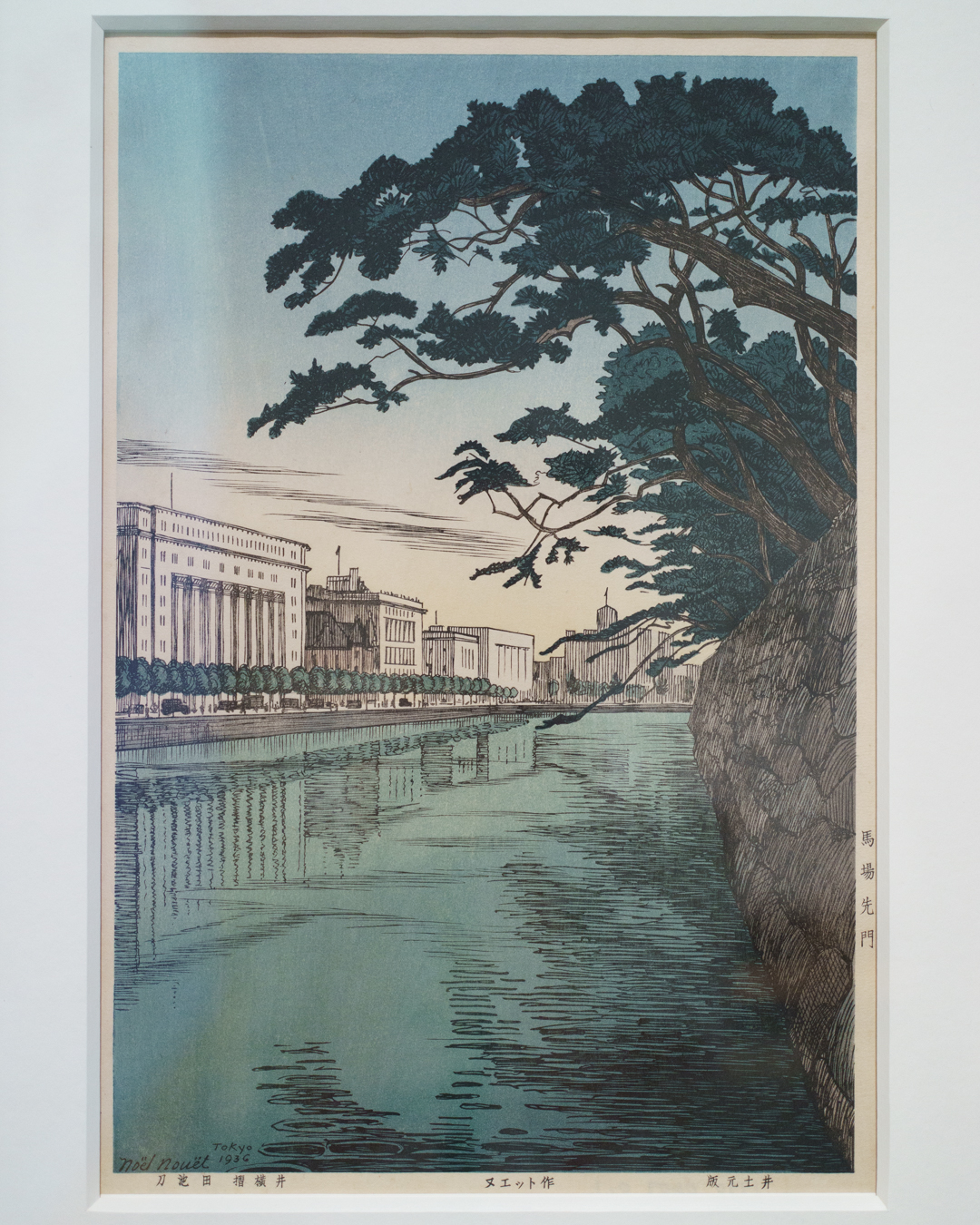

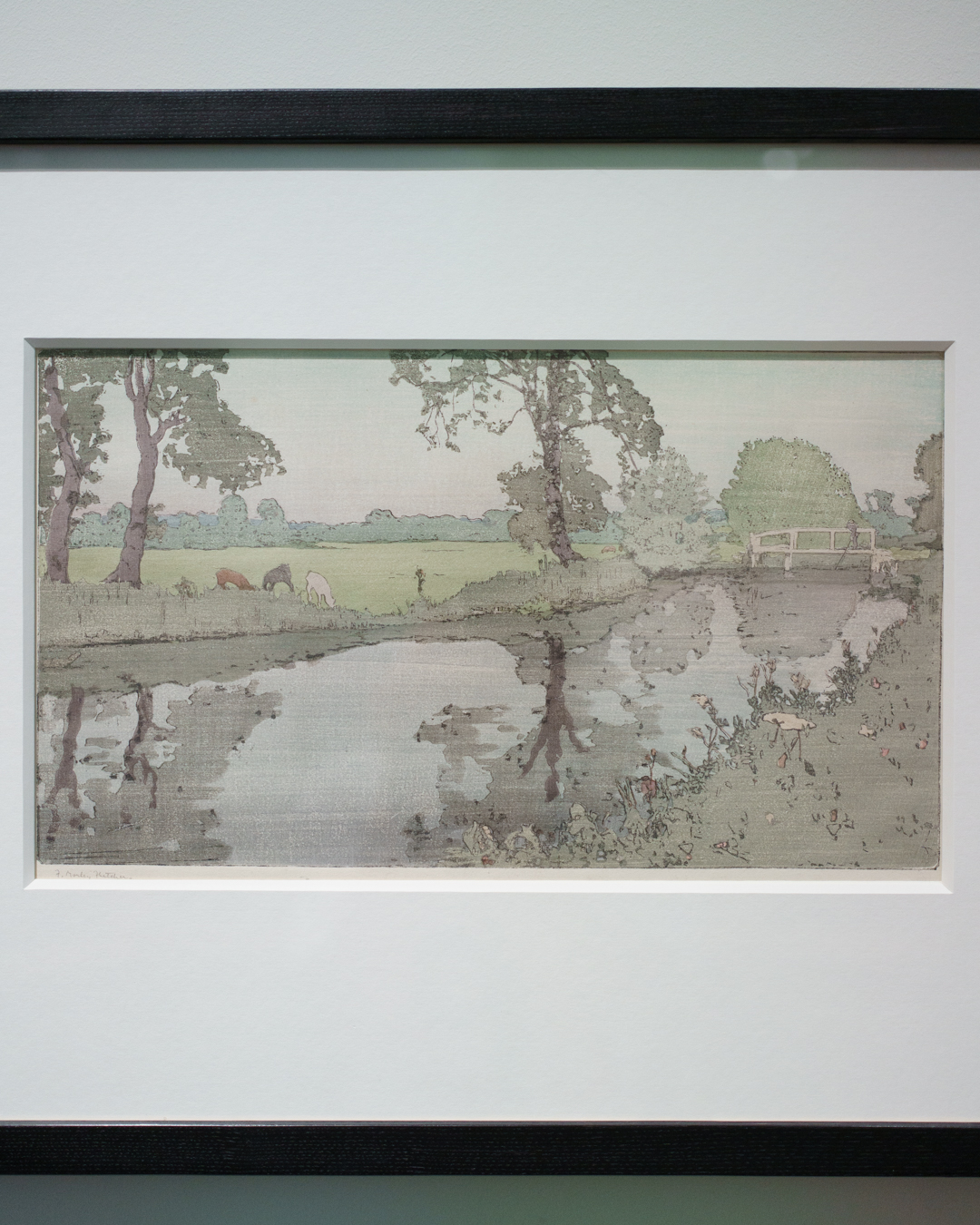

Japanese printmakers like Kobayashi Kiyochika, Kawase Hasui and Hiroshi Yoshida were obvious choices, and I was glad to see Frank Morley Fletcher represented too, given his crucial role in introducing Japanese woodblock printing techniques to British artists like William Giles. Elsewhere, Noda Tetsuya’s modern Diary: Feb. 23rd ’02, in London formed an unlikely pair with Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge, while Emily Allchurch offered a reinterpretation of Hiroshige’s Suidõ Bridge and Surugadai.

This is a very eloquent exhibition that effortlessly introduces visitors to the unique contexts and graphic qualities of Japanese printmaking, in addition to Hiroshige’s biography and artistic output. Such a fine balance is hard to do. I love it.

Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road (1 May – 7 September 2025) is at the British Museum, London, https://www.britishmuseum.org/

Leave a comment