I don’t know what I expected of the Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition at the Musée Jacquemart-Andre, but it certainly wasn’t what I witnessed a few months ago.

Artemisia, Héroïne de l’Art features 28 works by the shining female torch of Italian Baroque art, aiming to illustrate how she was both influenced by and broke away from her father Orazio and their mutual inspiration Caravaggio, who is represented by a single painting: The Crowning of Thorns (Banca Popolare di Vicenza).

In total, 41 works are gathered here over eight thematic rooms; 11 previously featured in the National Gallery’s larger retrospective in London in 2019-20.

The unique selling point in Paris is the display of newly attributed works by Artemisia – many from private collections – and a chance to view at eye level the newly restored Allegory of Inclination from the ceiling of the Casa Buonarroti, Florence.

However, due to the terrible quality of many of the works attributed to her, it really doesn’t show Artemisia in a particularly good light. Among them is the Cannes variant of Detroit’s large Judith and Her Maidservant, which contains notable differences, absences, and has terribly flat tonal modelling; it is the second of three versions of this composition, the last being in Naples and just as rough.

Since the exhibition makes no specific mention of her well-known collaborators, this may offer an explanation for the uneven quality of the works presented, especially in her later years. This is noticeable in the seventh room which is devoted to portraits of mythological and religious heroines, as well as mentioning her Naples workshop from 1630 onwards, and the need to reuse compositions to meet demand.

Although the drapery in the fictive portraits often shimmer with light and texture, the all-important faces are often unconvincing and lifeless. I suspect Artemisia’s personal contributions were more complicated and nuanced than this exhibition lets on, unless there was some unknown historic trend to overpaint or fix up her paintings out of spite.

By contrast, there isn’t a single bad painting by Orazio in the show, which are practically luminous; one exception is the Bilbao version of Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, here presented next to Artemisia’s Uffizi one. They were even able to project the duo’s celebrated Allegory of Peace and the Arts on to the ceiling of the opening, which originally adorned that of the Great Hall in the Queen’s House at Greenwich.

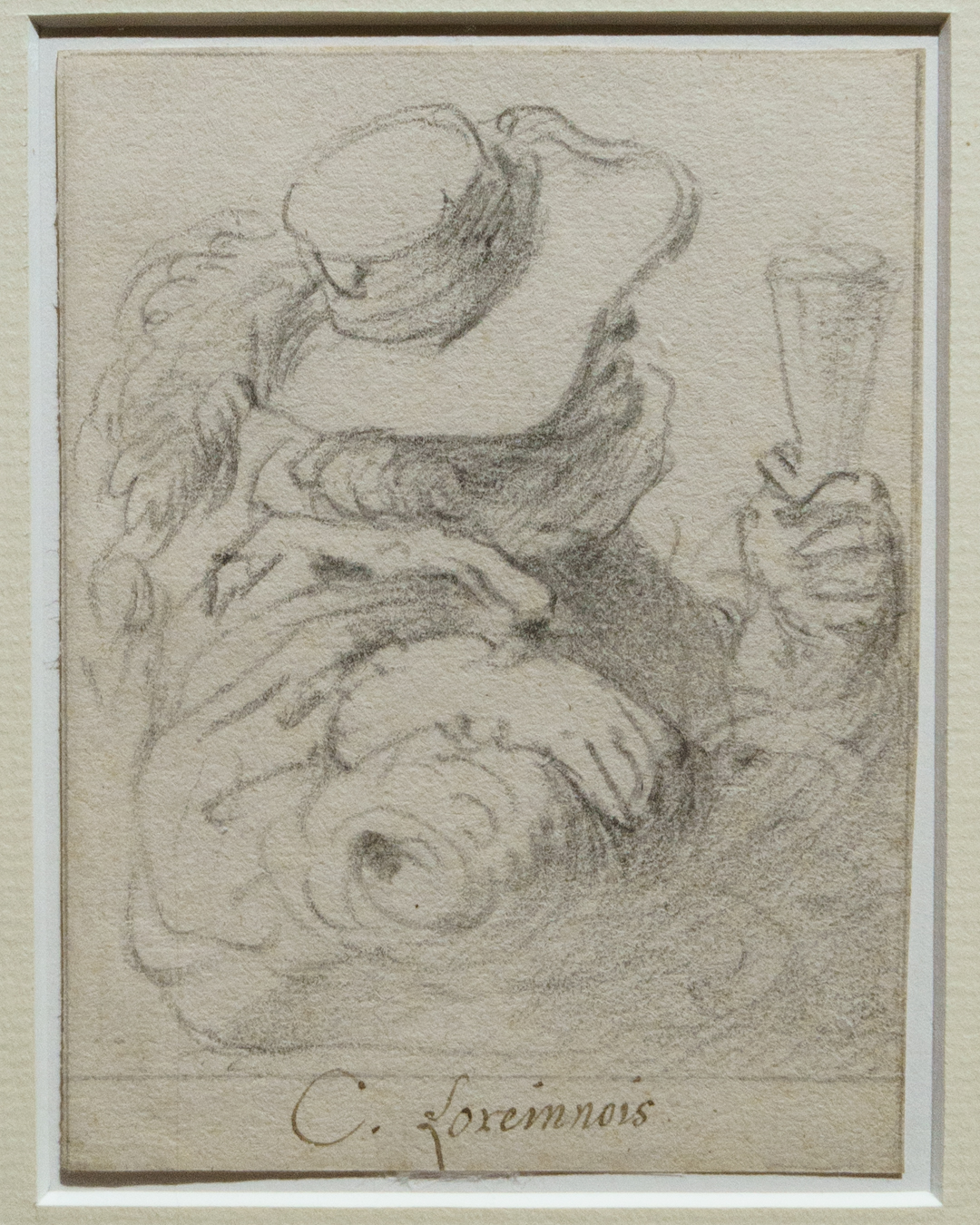

While I could complain endlessly about things like how the narrow corridor was occupied by a copy of the more recognisable Judith Slaying Holofernes – solely a crowd-pleaser in the absence of the two prime versions – leaving no room to step back and appreciate the Casa Buonarroti panels, or the intermission room with just Leonaert Bramer’s five drawn portraits of Caravaggisti including Artemisia disguised as a moustached male, it is probably more useful to highlight the works that actually brought me joy because I know Artemisia was better than this.

While much of her output seems to focus on a muted palette of brownish hues, certain works demonstrated her jewel-like application of colour, from the tiny Danaë (Saint Louis Art Museum) to the large Cleopatra (Galerie G. Sarti, Paris), and even her very early Susanna and the Elders from Pommersfelden. I was also blown away by the head fragment of an Annunciate Virgin (private collection). These are fine examples of her superiority over her father in this category.

While the exhibition has genuinely interesting and rare things to see, it is plagued by a general lack of critical stylistic judgement. Every attribution is presented as definitive, with no chance for an ‘attributed to…’ nor ‘…and workshop’. Whether this is because of a fear that loans could be pulled over a ‘downgrade’, or that the curators truly do believe these attributions, we may never know.

Despite the torrential waves of scholarly and public interest in Artemisia in recent years, I expected better judgement on the part of institutions and their curators. Sensationalism and academic discourse are not mutually exclusive.

But as it stands, the Paris show feels like someone looked at several auction catalogues and started ticking boxes like an ‘Artemisiac’.

Artemisia, Héroïne de l’Art (19 March – 3 August 2025) is at the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, https://www.musee-jacquemart-andre.com/fr

Leave a comment