If you haven’t heard of the Brown Collection yet, this is your reminder to pay them a visit. Located a short walk away from the Wallace Collection, it houses the personal art collection of the British artist Glenn Brown in dialogue with his own works as part of a rotating display. As an ‘appropriation artist’, he only buys works that he can learn from and incorporate into his own creative practice. His surrealistic engagement with the Old Masters is what captivated me in the first place many years ago.

Spread across four stories of gallery space, the current exhibition – The Laughing Stock of the Heartless Stars – is a rich presentation of works covering 500 years of art history from Hendrick Goltzius to Ann-Marie James. For a collection so eclectic, I was amazed to find an impressively coherent display. The ground floor examines still lifes and botany, featuring clay sculptures by Phoebe Cummings, photography by Nobuyoshi Araki, and a wonderful painting of tea roses by Henri Fantin-Latour.

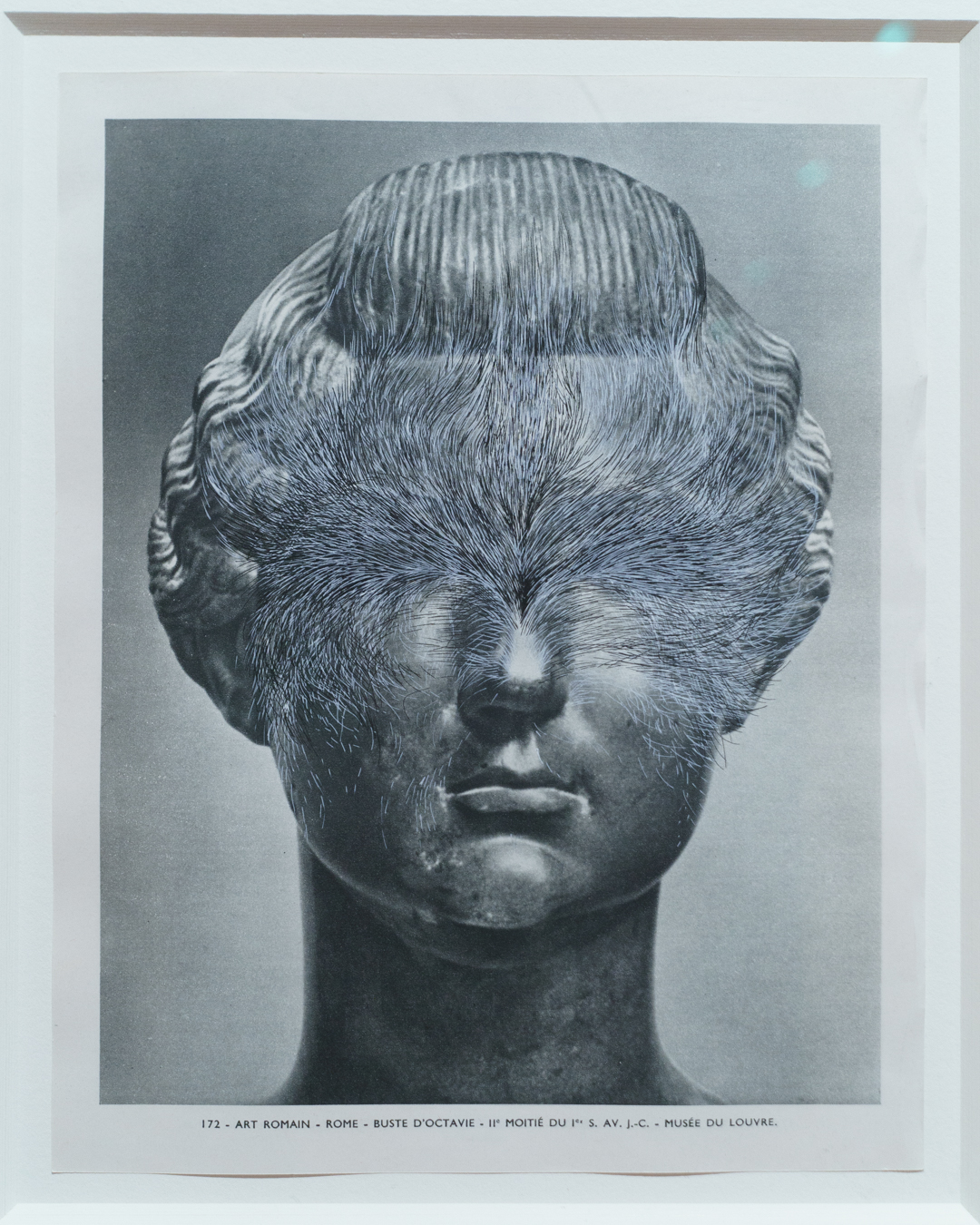

On the first floor, we find two lounge chairs in the middle of a colourful room devoted to heads and portraits, the kind of subject matter that is probably most associated with Brown’s work. Indeed, we find ourselves face-to-face with his hybrid faces, juxtaposed with sheets of head studies by Mauro Gandolfi.

Commedia dell’arte underpins this room, featuring Venetian girandoles disguised as carnival figures, an actual clown drawn by Laura Knight, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s A Boy as Pierrot (c.1785) turned upside down in Brown’s own interpretation of the Wallace Collection’s original. The smoky draughtsmanship of Austin Osman Spare’s drawings also evokes Brown’s signature wispy lines.

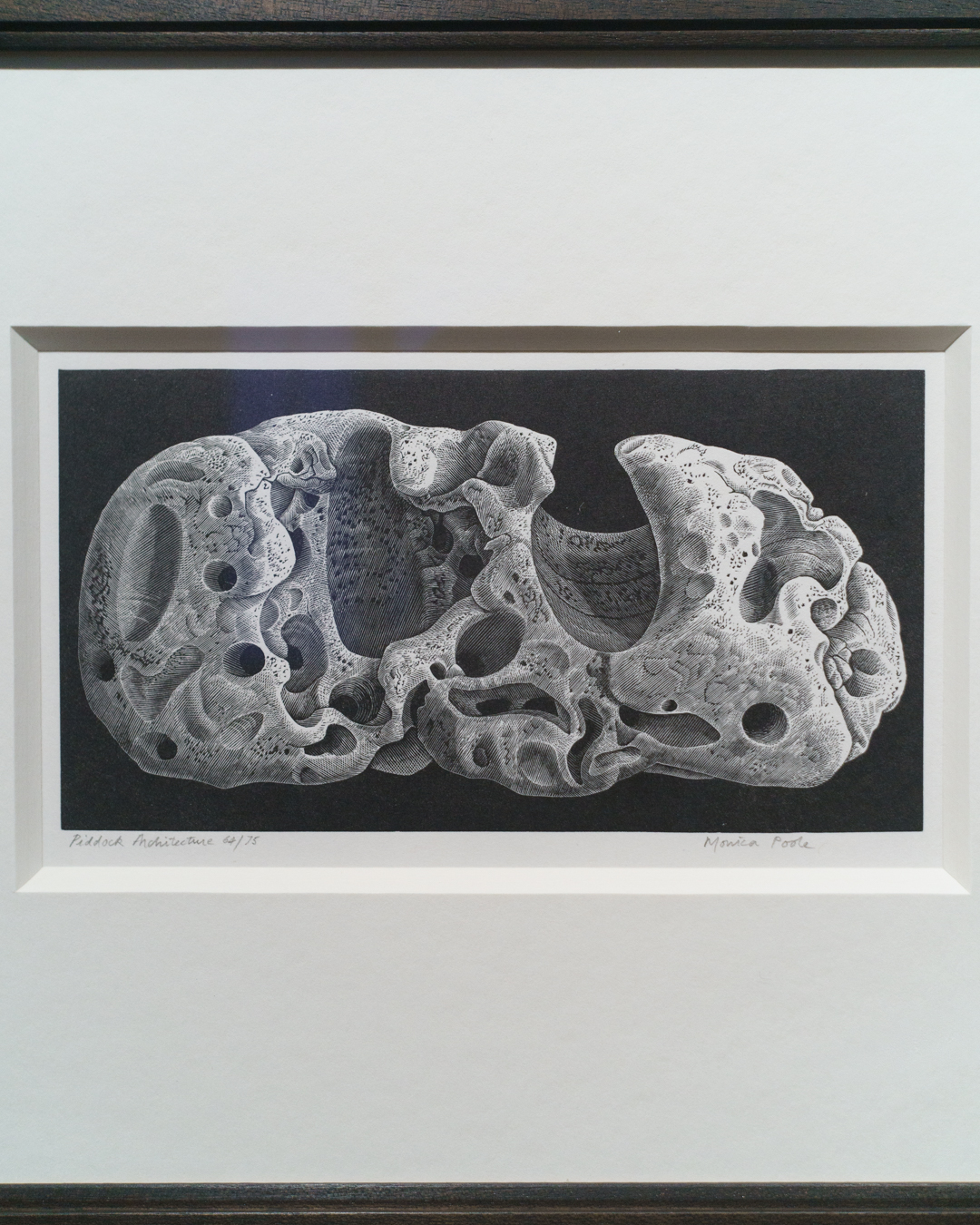

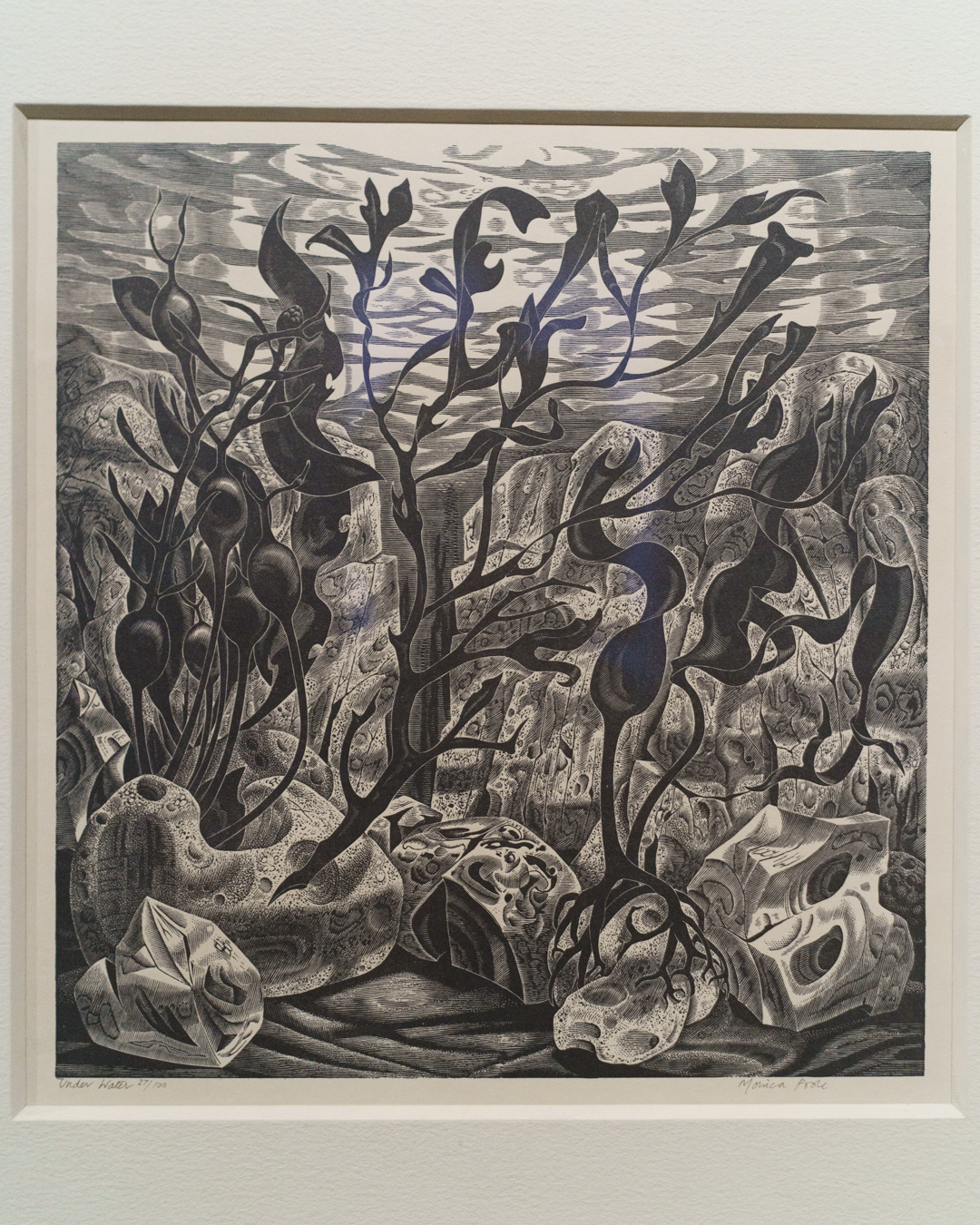

Meanwhile, the second floor captures Brown’s early interests in landscape and the sublime. The dominant painting in the room is the Zabludowicz Collection’s The Aesthetic Poor (for Tim Buckley) (2002), inspired by John Martin’s mezzotint The Fall of Babylon (1831) shown next to it. In one corner, the cosmological undertones of the room features a Qing dynasty scholar’s rock (gongshi) on the floor appearing like the craterous surface of the Moon, while Monica Poole’s Piddock Architecture (1975) looks just like a meteorite.

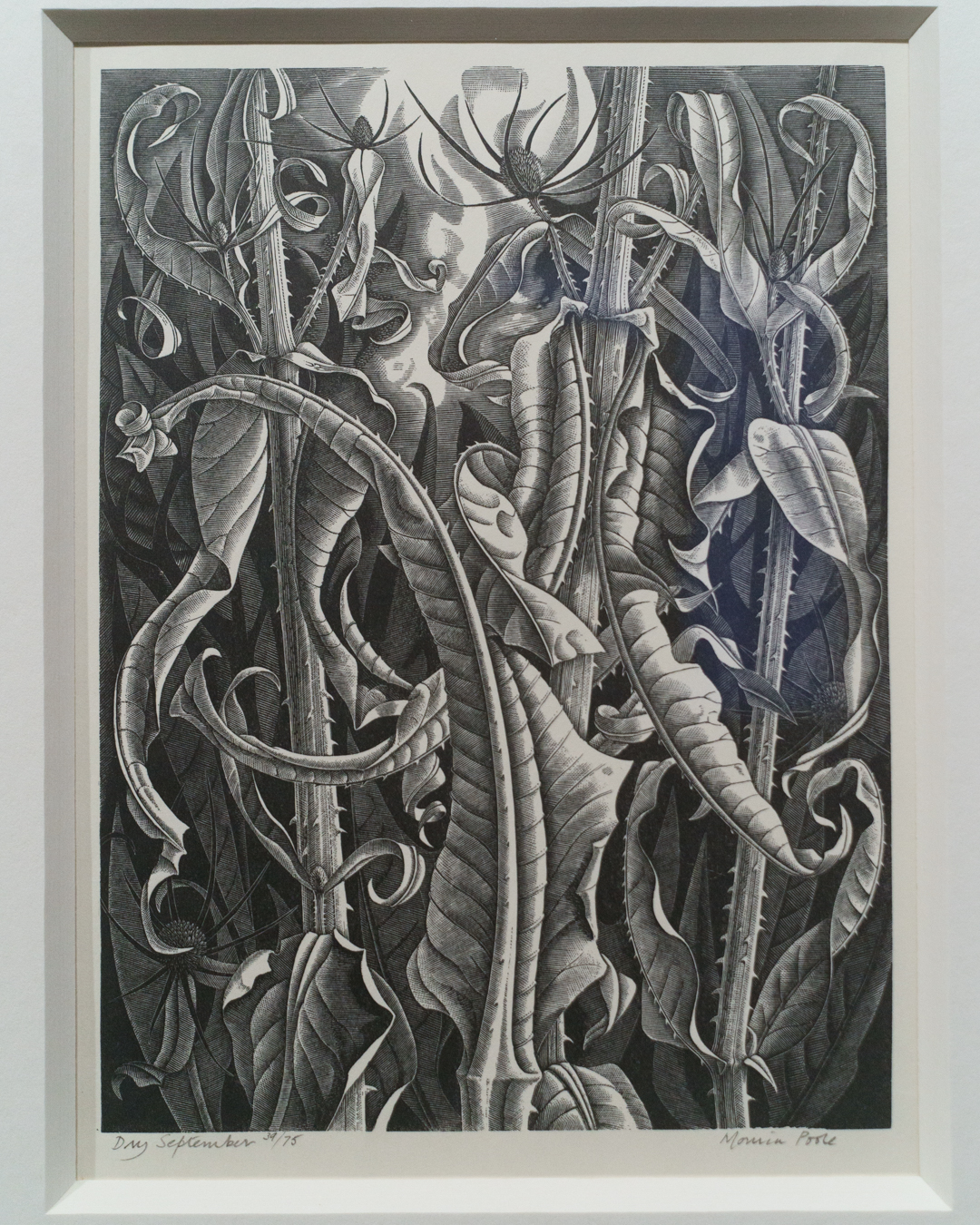

In another corner, a group of tree-themed works entertains themes of anthropomorphism, where organic subject matter somehow lends itself to wobbly forms similar to the stylised figures of 16th-century Dutch artists like Abraham Bloemart and Joachim Wtewael on the opposing wall.

Surprisingly, the best part is in the crypt-like basement. Devoted exclusively to sculpture, one finds a kind of homage to figuration across the ages. Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s L’Amour Blessé (1873-75) invites us into the space, where we pass Anthony Caro’s Table Piece CLXXXII (1974) – perceived as a kind of reclining figure – and reach Brown’s recent marble sculpture Morbid Fancies (2024), which morphs from a classical figure into spirited flecks of oil paint and impasto. Yet the most playful object turns out to be another scholar’s rock, whose naturally serpentine form is eerily reminiscent of Adriaen de Vries’ Mercury and Psyche (1593), depicted in Jan Harmensz. Muller’s masterful engraving at the end of the room.

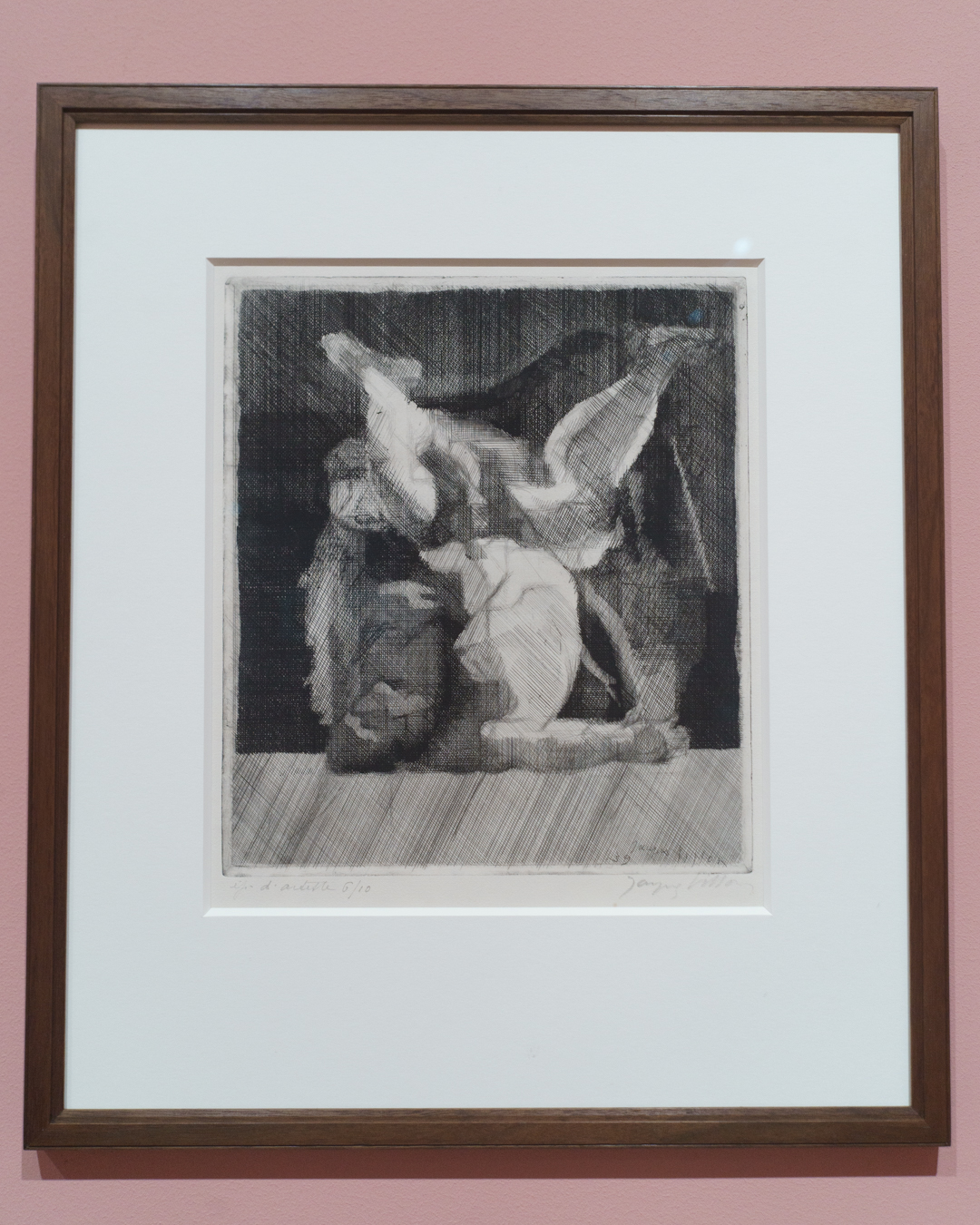

Perhaps the most valuable aspect about the Brown Collection is its potential to showcase works by forgotten, yet significant artists like the surrealist painters Grace Pailthorpe and Marion Adnams. Brown seems unrefrained to buck the trend in contemporary collecting, a refreshing outlook that offers visitors a chance to see unexpected things; I can’t think of another place where Jacques Villon etchings are so prominently displayed.

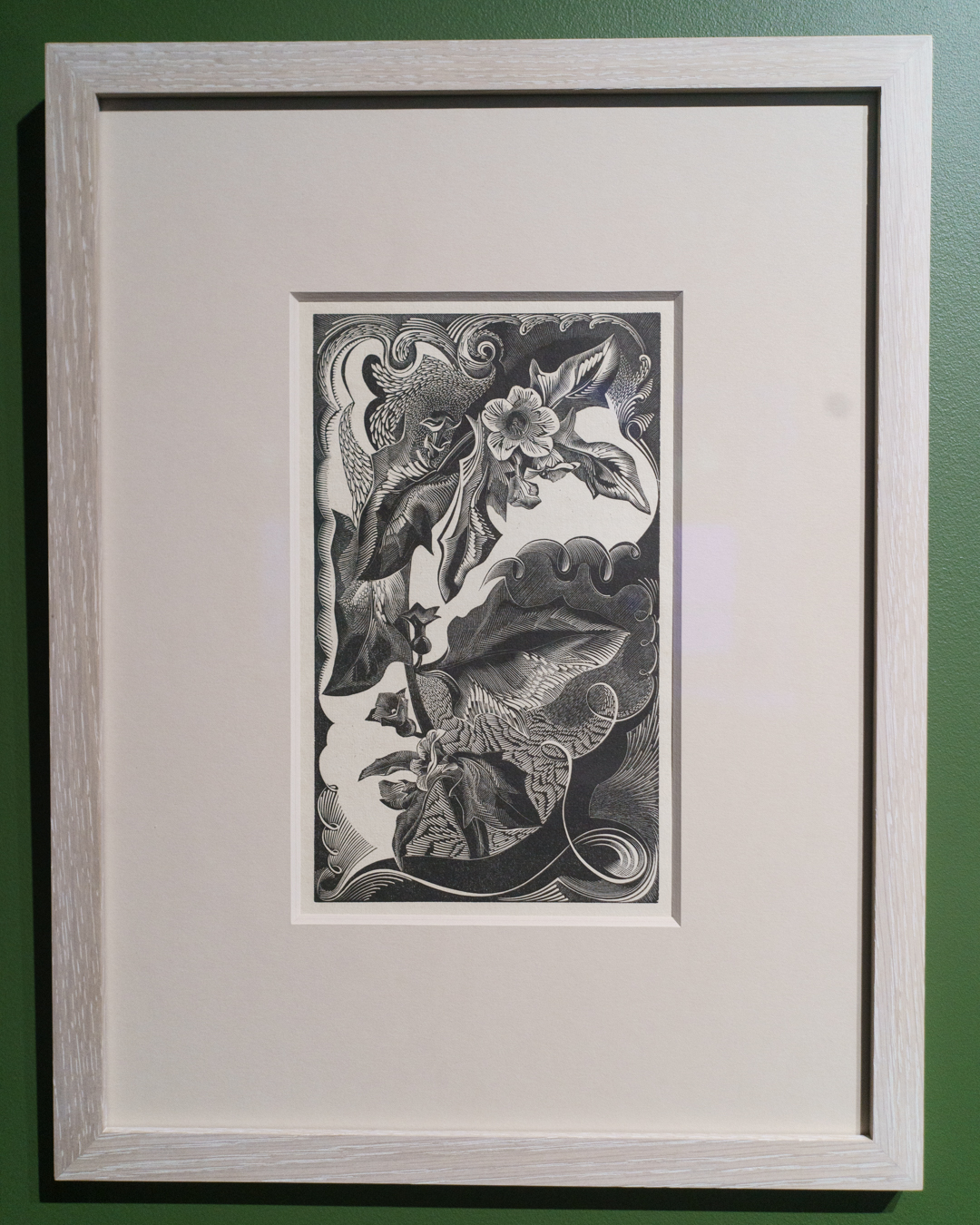

For example, I did not anticipate seeing wood engravings by Monica Poole and Gertrude Hermes, a relatively unfashionable area of print collecting due to the technique’s association with book illustration. Yet Brown is also exactly the kind of artist who can properly appreciate a wood engraver’s mastery of line, in the same way Goltzius’ burin carved the image of a Pietà (1596), a prized engraving that usually hangs in Brown’s studio.

Overall, the Brown Collection invites us to understand Brown’s work via the lens of art history in a manner that is meaningful and accessible. Where possible, each room contains an assortment of literature related to the artists or works exhibited, offering further avenues for thought. The collection is great to explore and free to visit. Or just go for the Goltzius chiaroscuro woodcut, as I did.

The Laughing Stock of the Heartless Stars (12 September 2024 – 2 August 2025) is at The Brown Collection, Marylebone, London, https://glenn-brown.co.uk/the-brown-collection/

Leave a comment