When we think of Japanese printmaking, images of beautiful courtesans, samurais, and Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831) immediately flood our consciousness. For many, these ukiyo-e prints (‘pictures of the floating world’) from the 17th to 19th centuries may seem like the country’s only contribution to the world of printmaking.

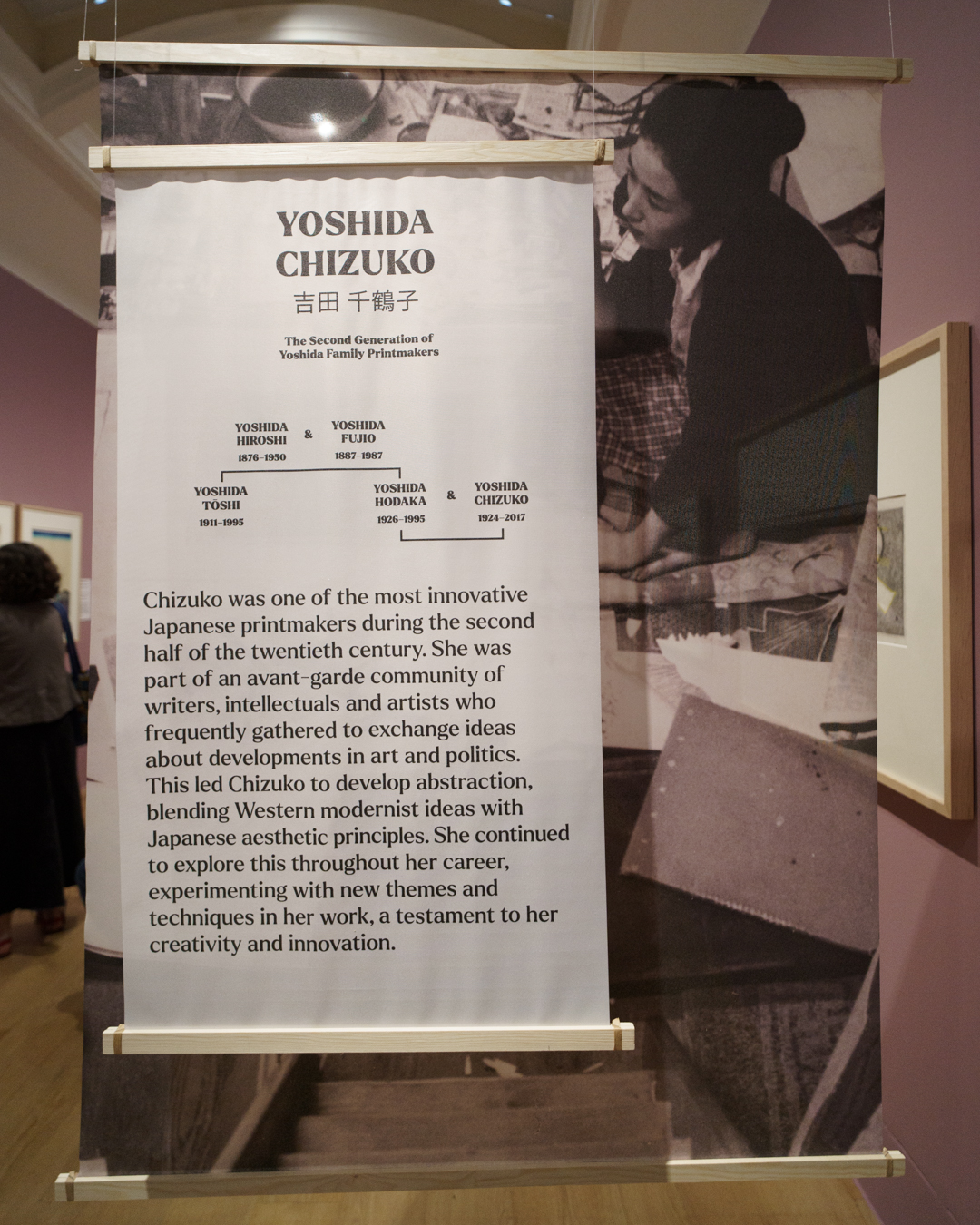

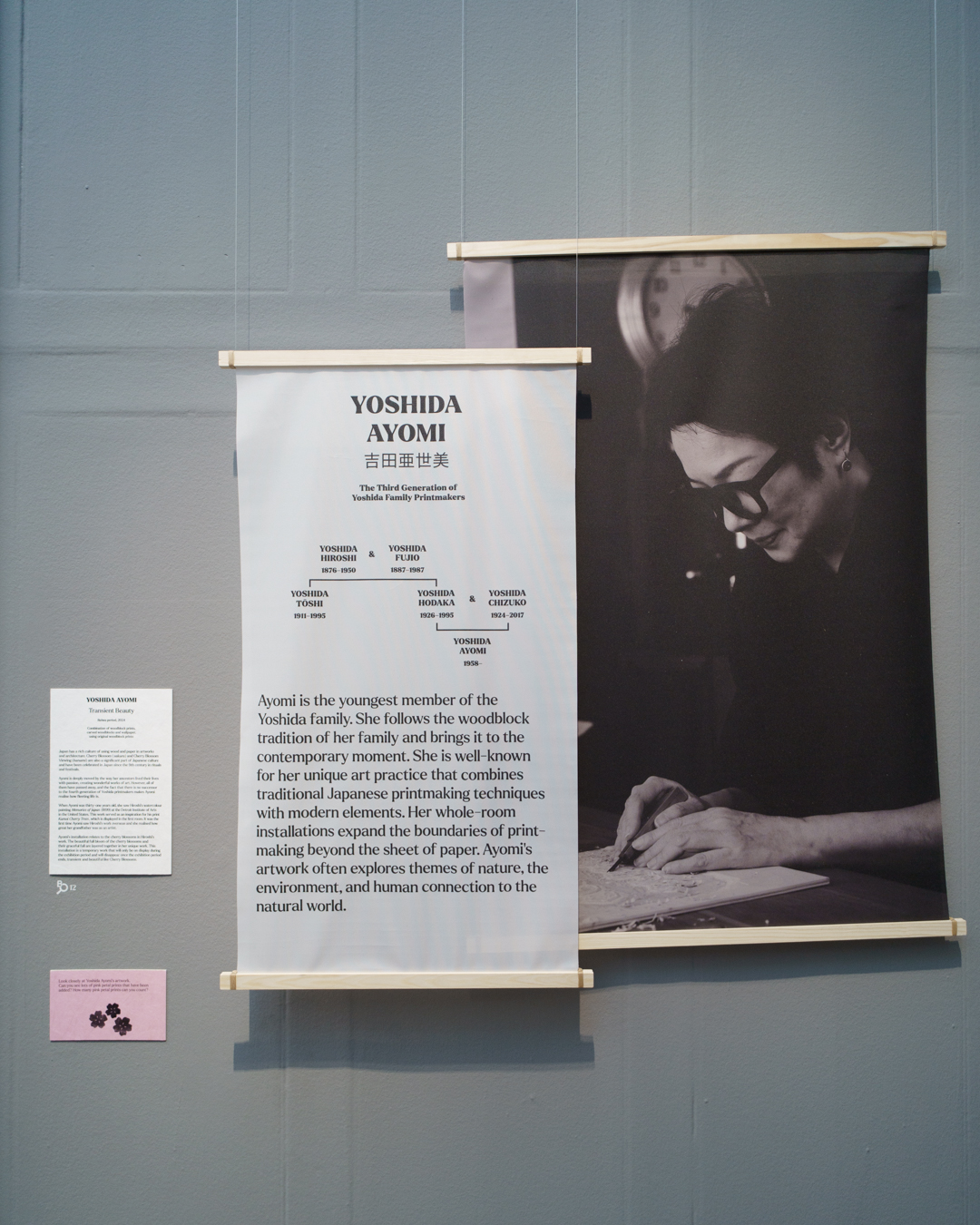

The Yoshida exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery finally addresses this imbalance with an unbroken survey across three generations of the Yoshida family starting with Yoshida Hiroshi, one of the pioneers of the shin-hanga (‘new prints’) movement. The gallery’s visitor book records his visit on 29th May 1900.

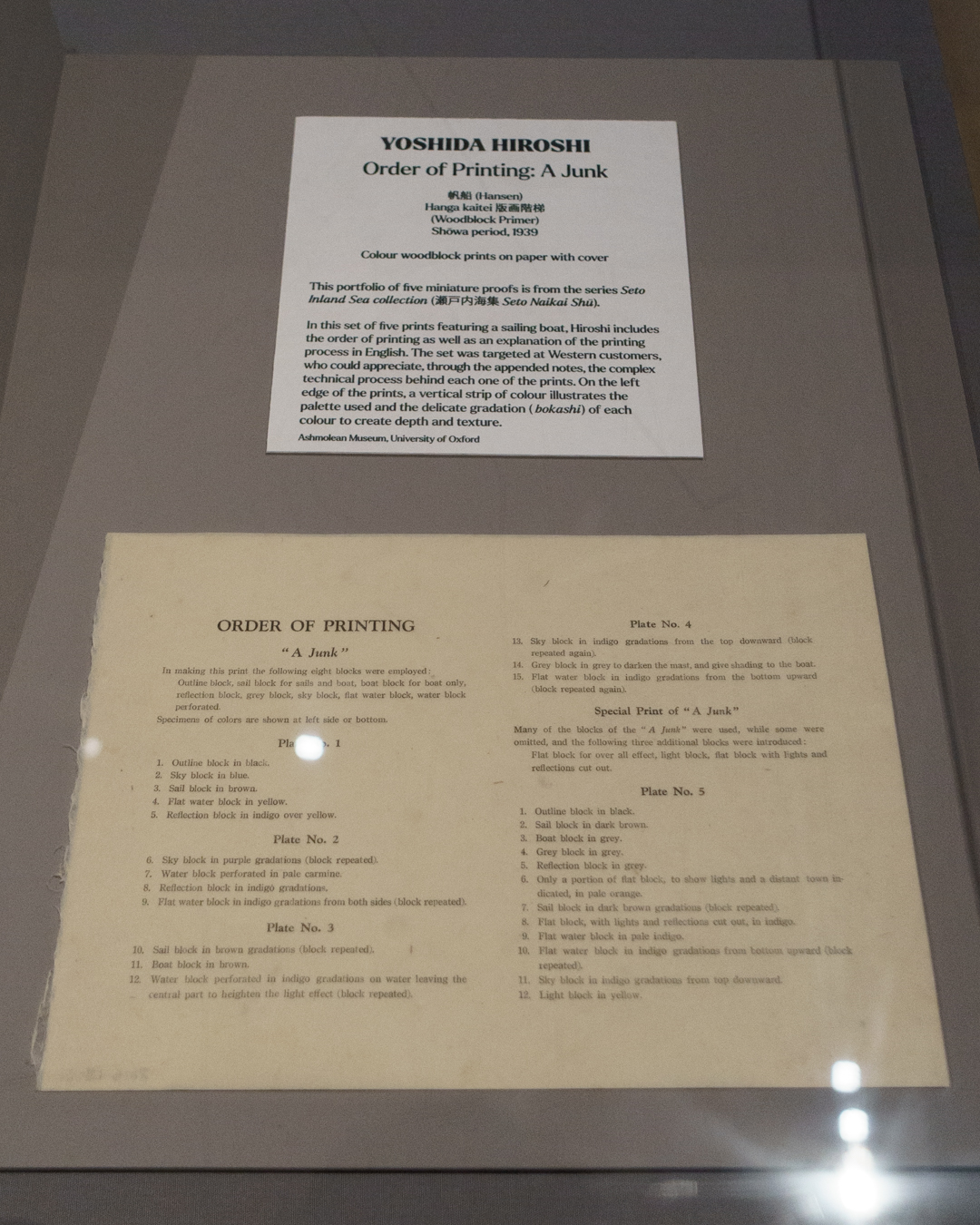

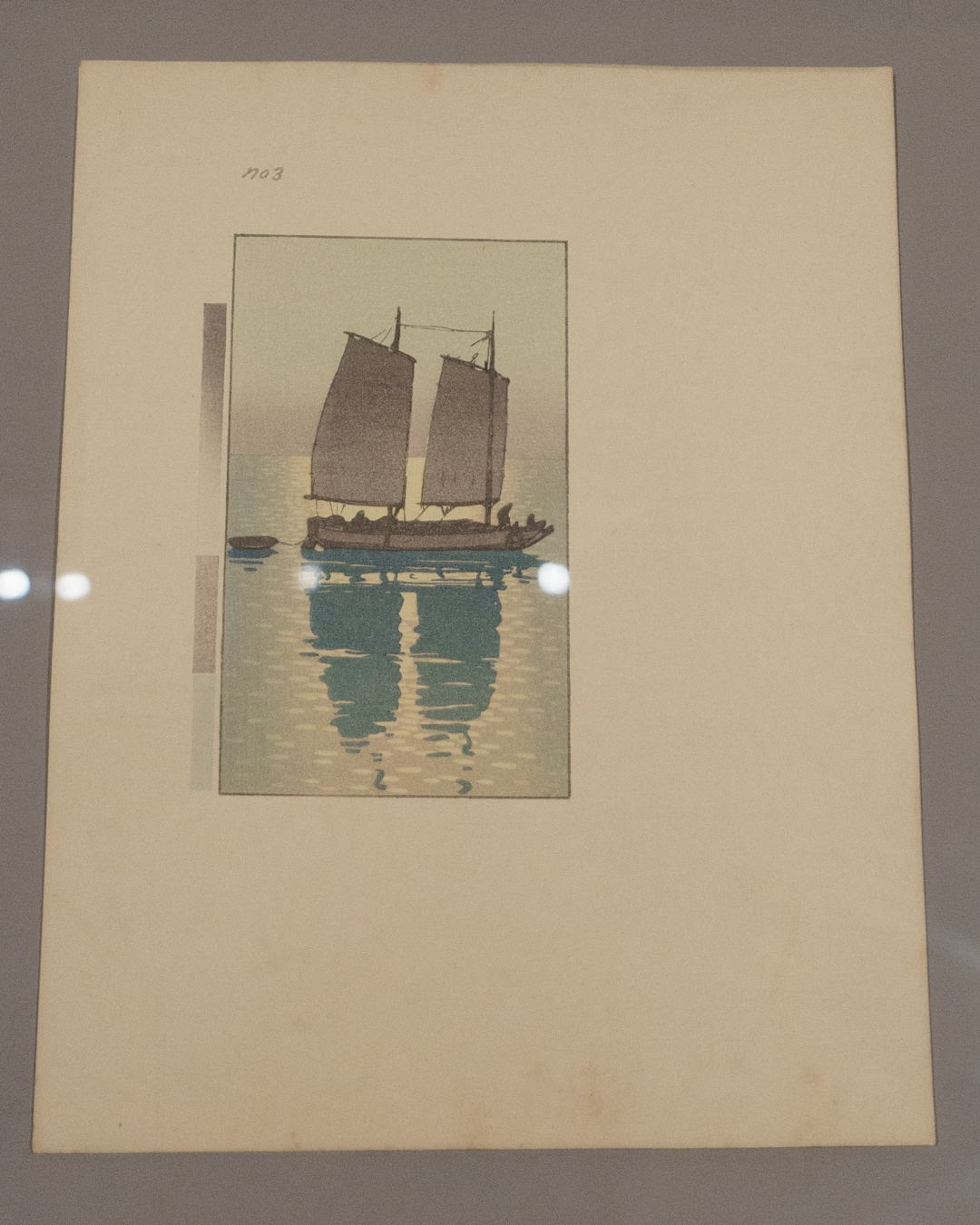

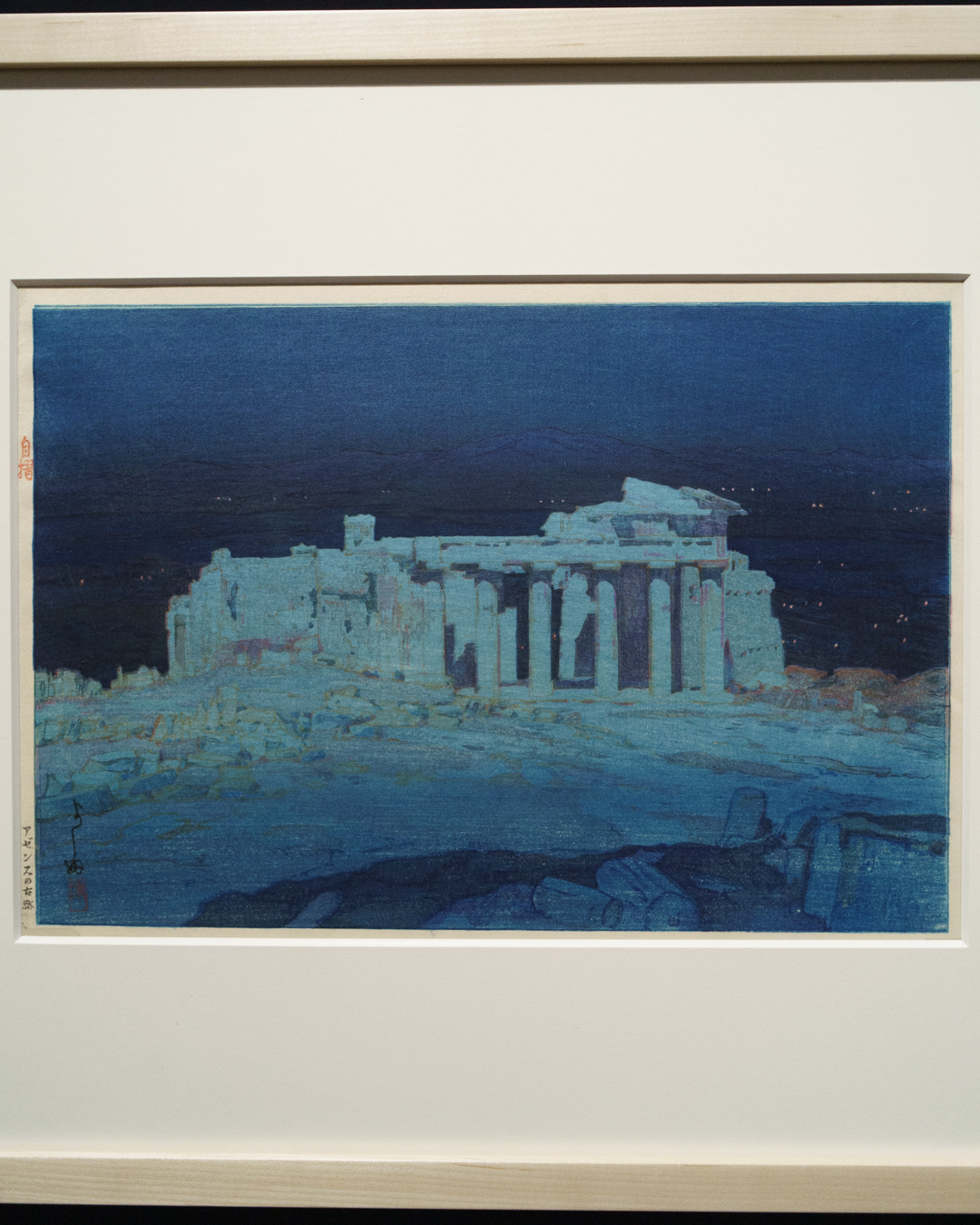

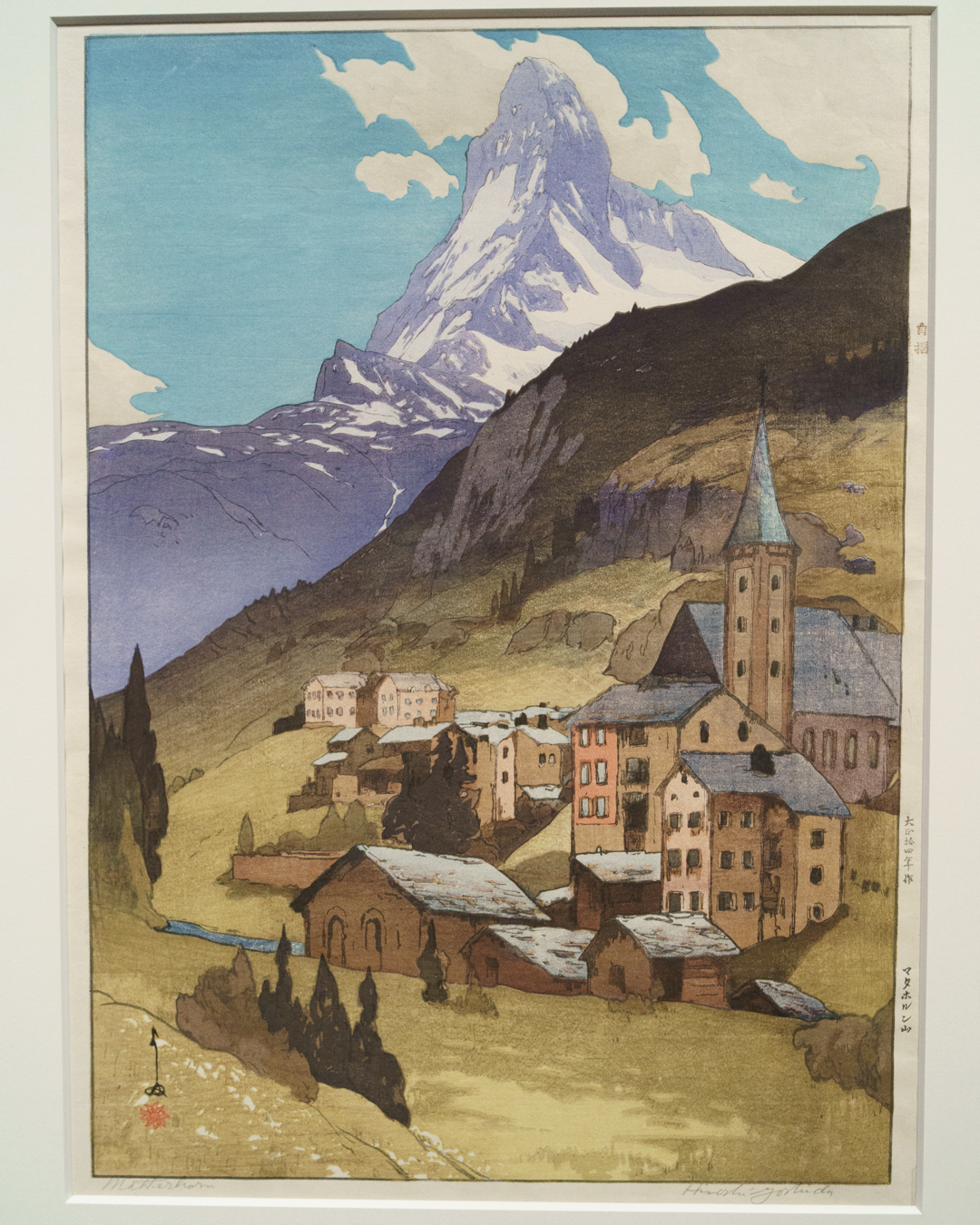

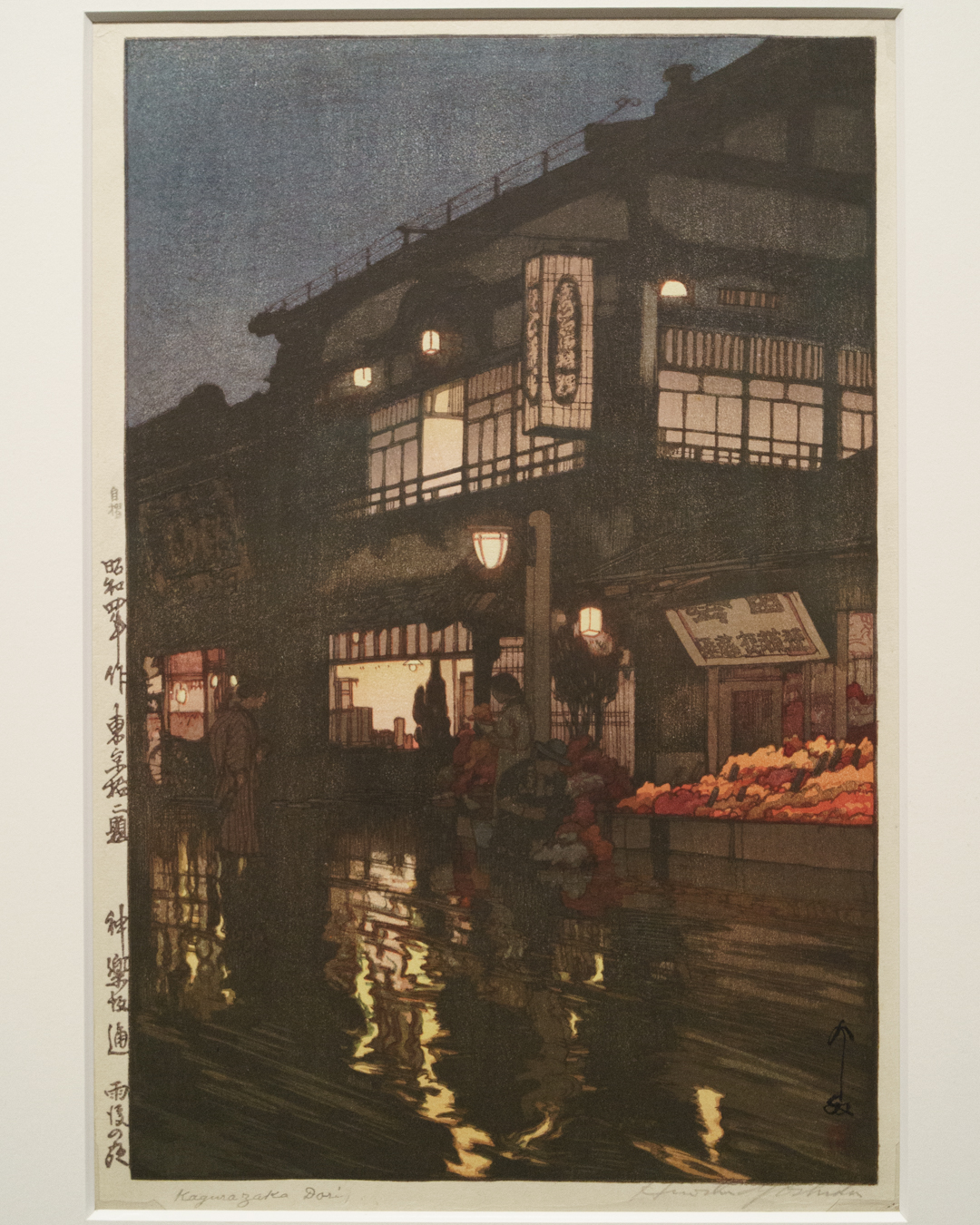

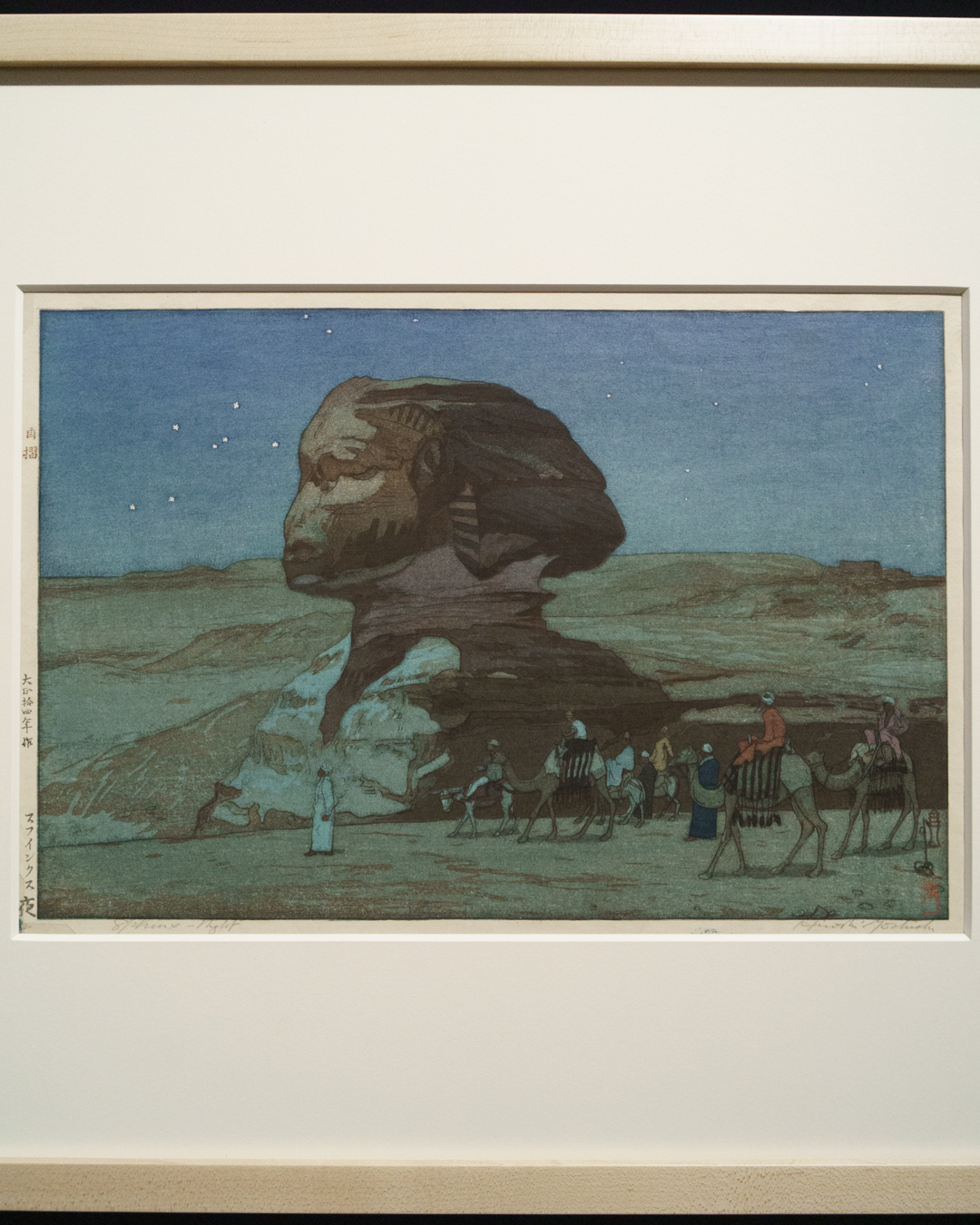

In the first room, we see Hiroshi’s depictions of Japanese and international landmarks, utilising Western artistic tropes like proper perspective, while reviving the collaborative production system of the ukiyo-e tradition where labour was divided between the artist, carver, printer, and publisher. Especially interesting are the different versions of single images, such as the Taj Mahal or Great Sphinx, both depicted as either day or night scenes.

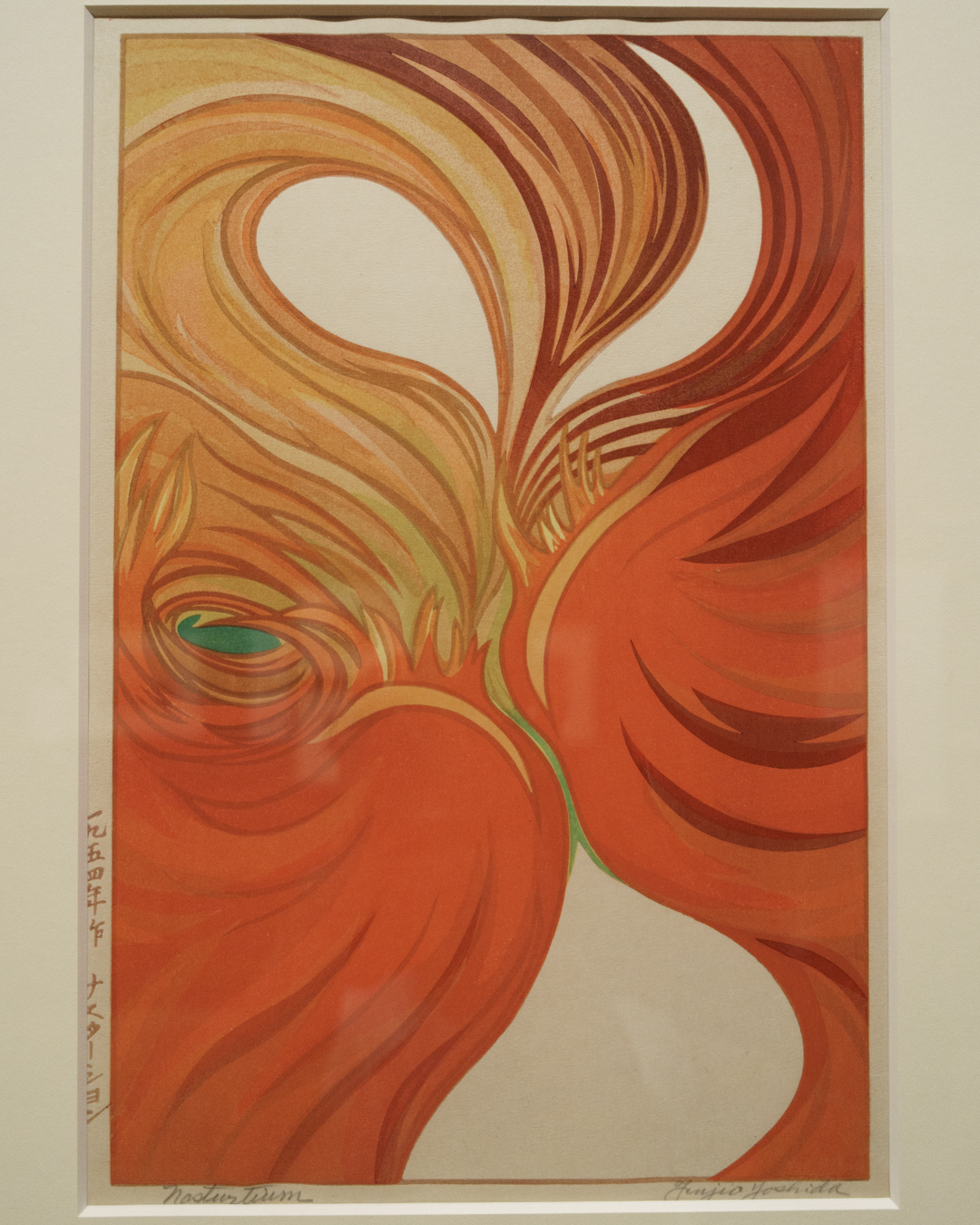

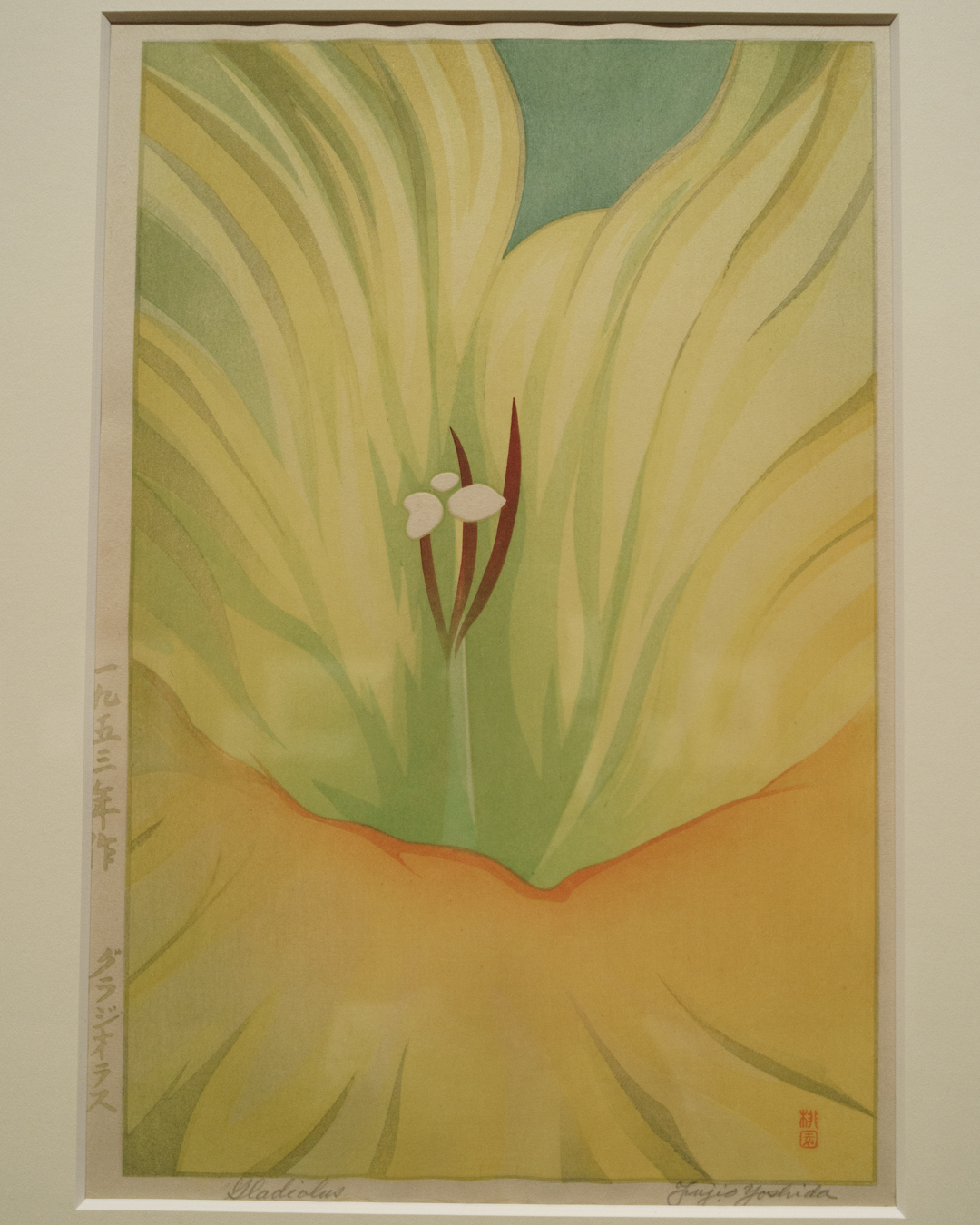

Hiroshi’s wife Fujio was also a major innovative artist in Japan; she is represented here by her close-up prints of flowers which could easily rival Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings.

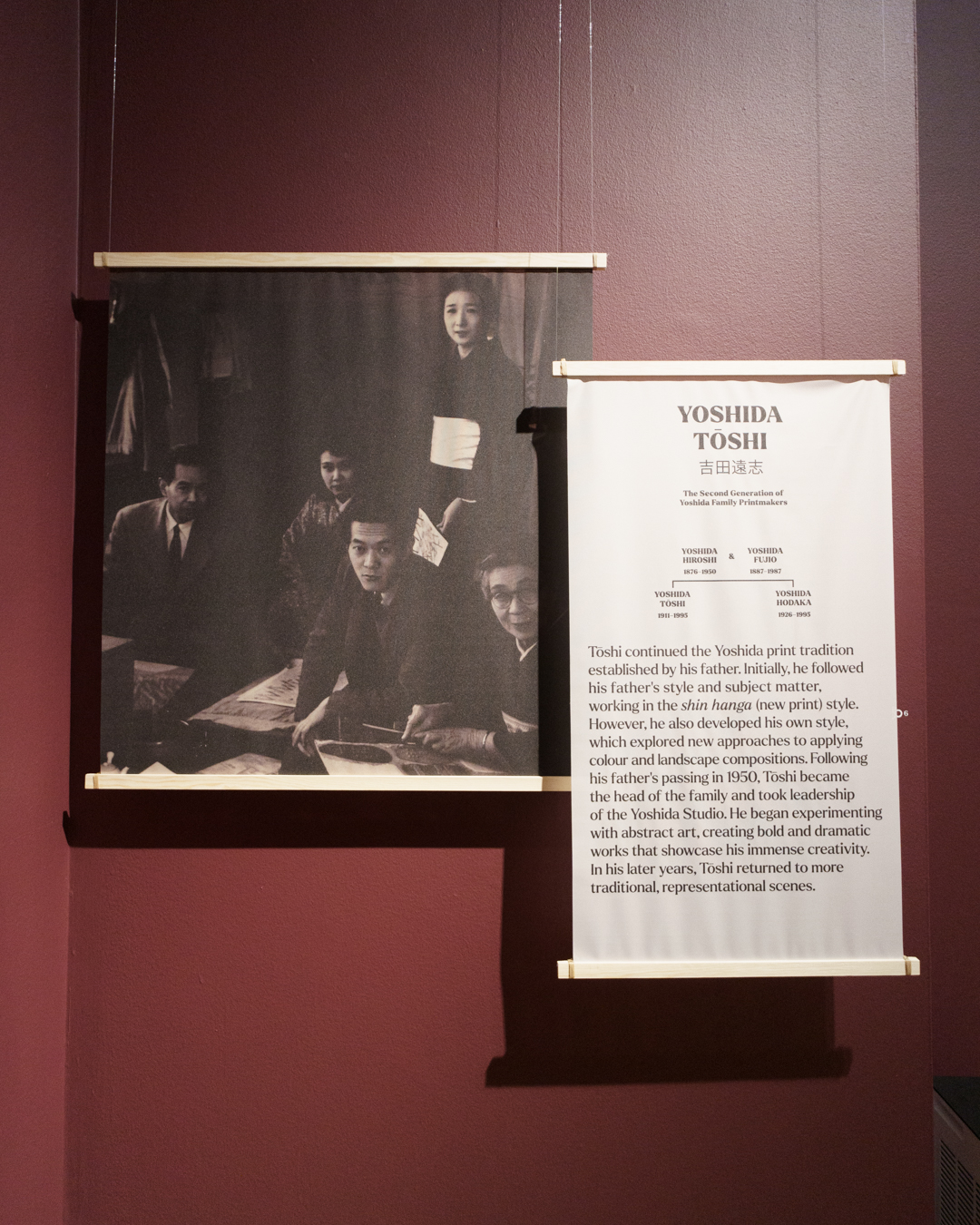

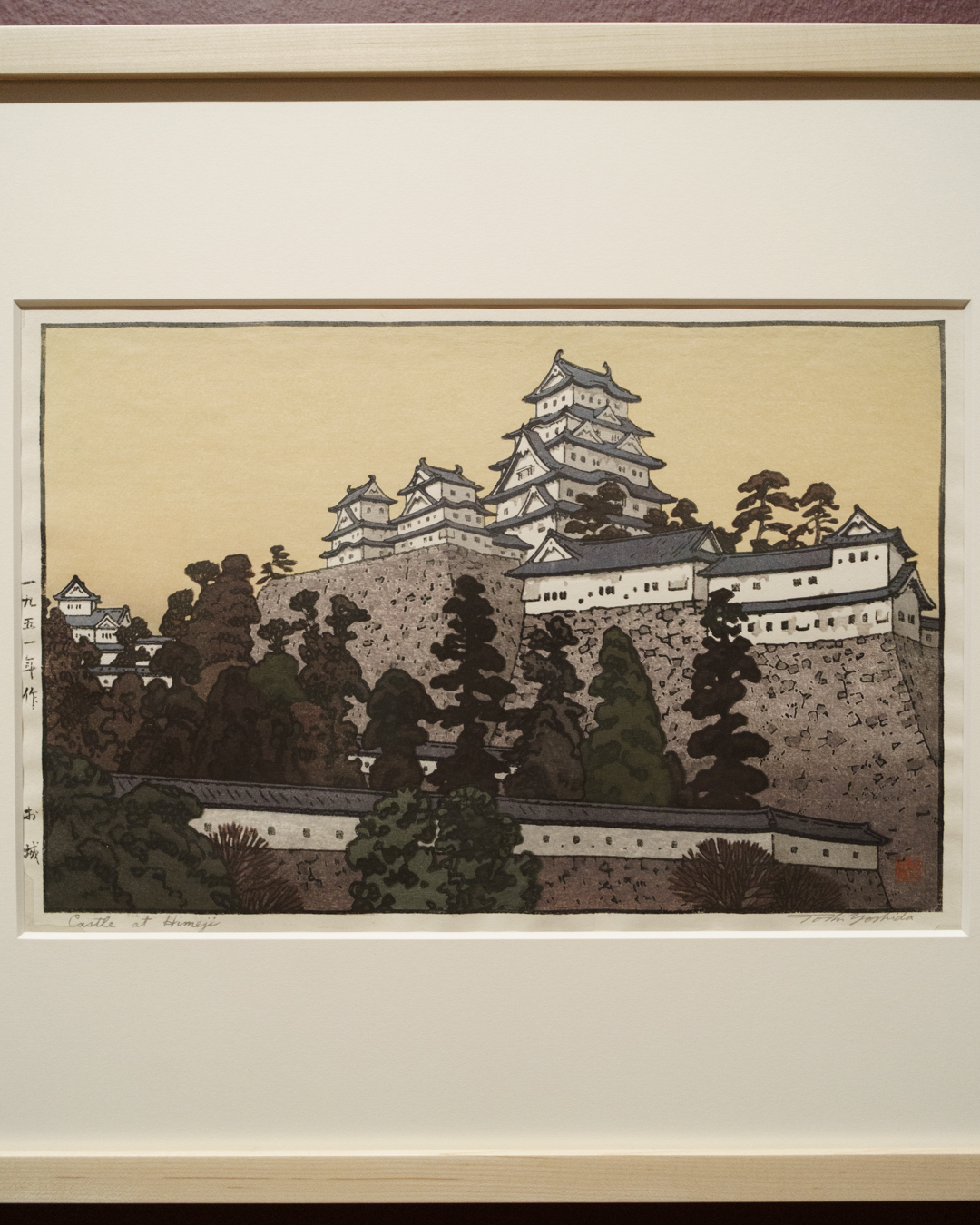

This modern, abstracting approach to subject matter feeds nicely into their eldest son Tōshi’s work, whose continuation of depicting local landmarks is combined with a formal interest in geometry, colour, and the texture of print.

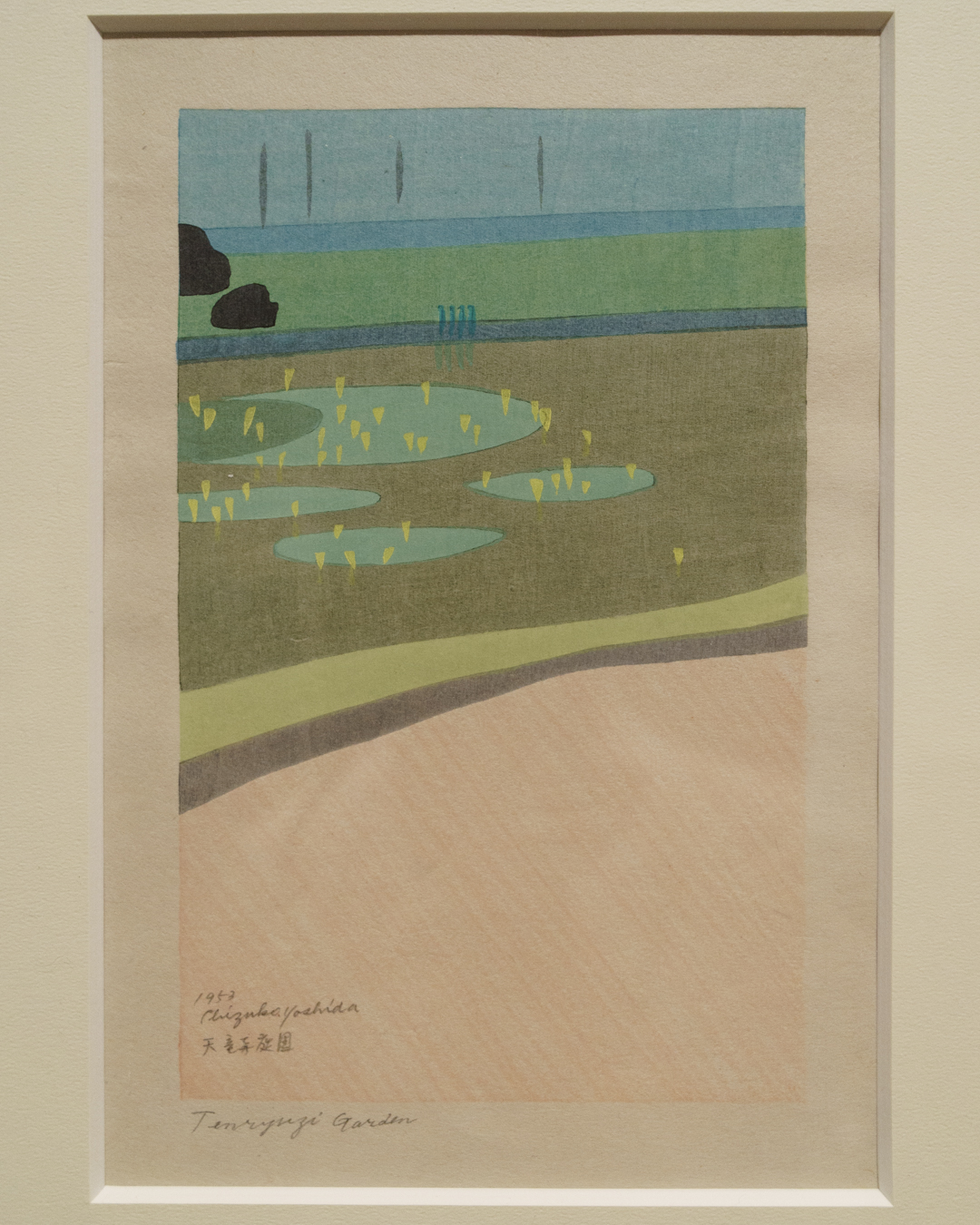

In Tenryuji Garden (1963), the raked lines of the rock garden are created by blind-stamping alone; it is part of his White-line print series where black lines are replaced with white outlines instead.

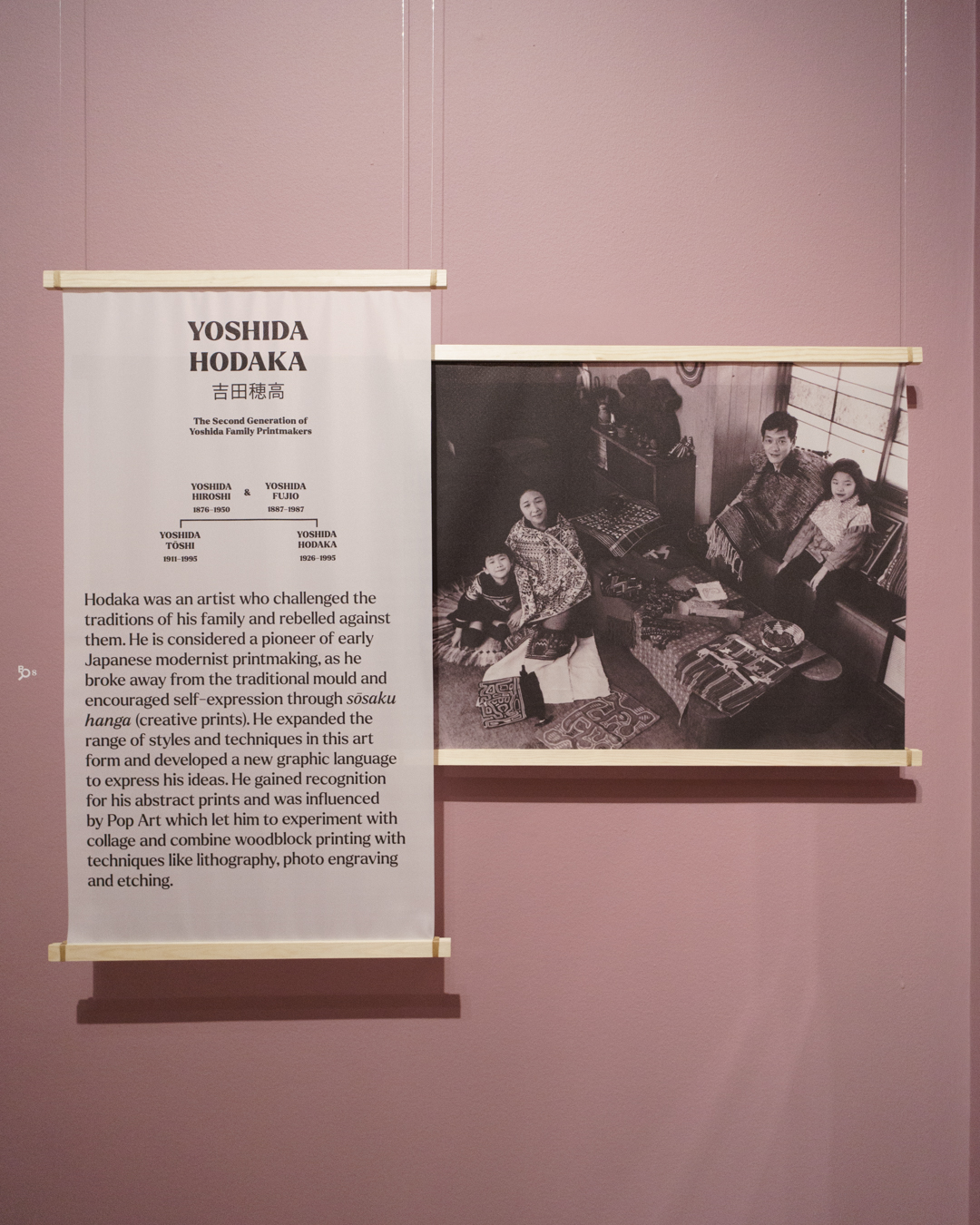

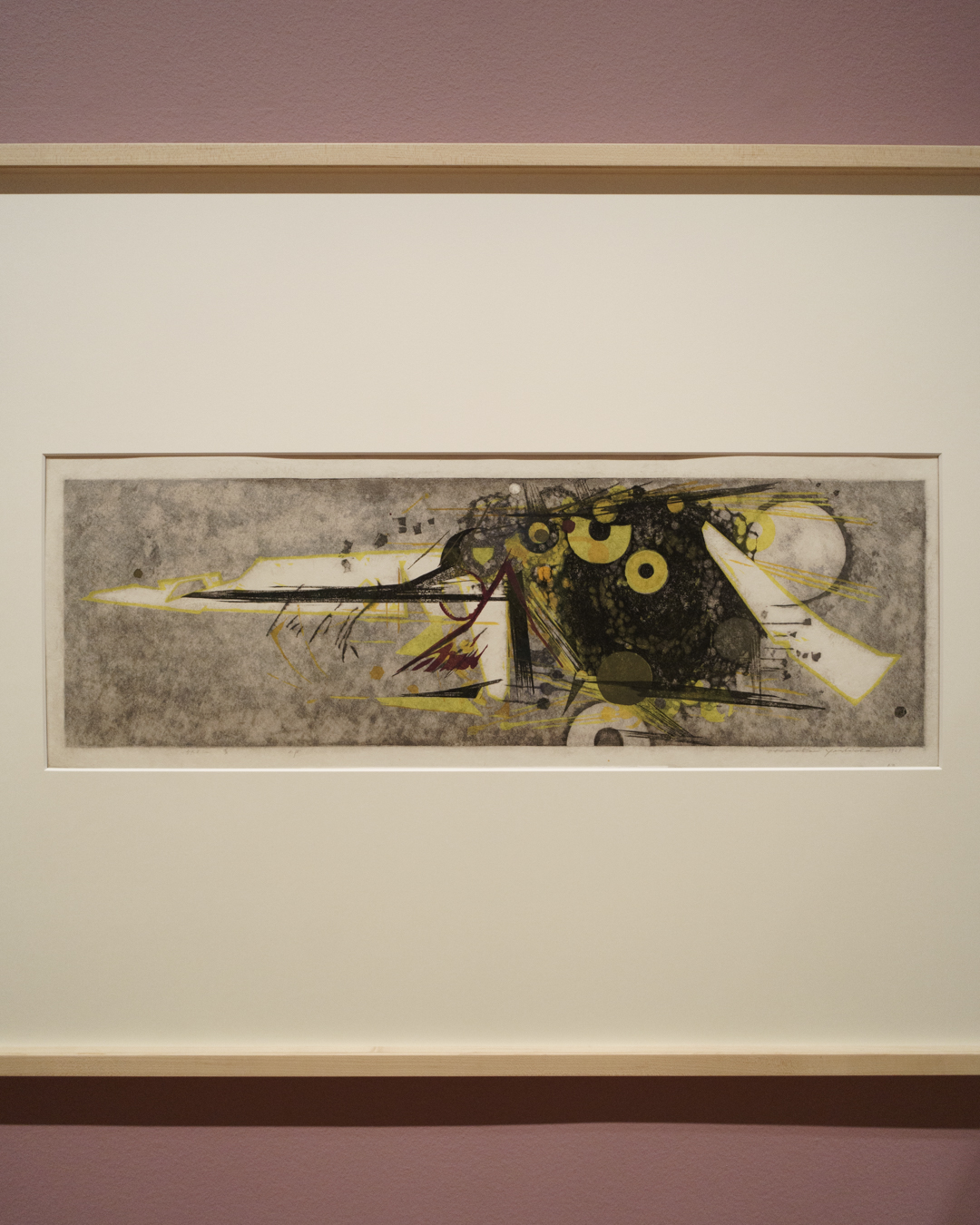

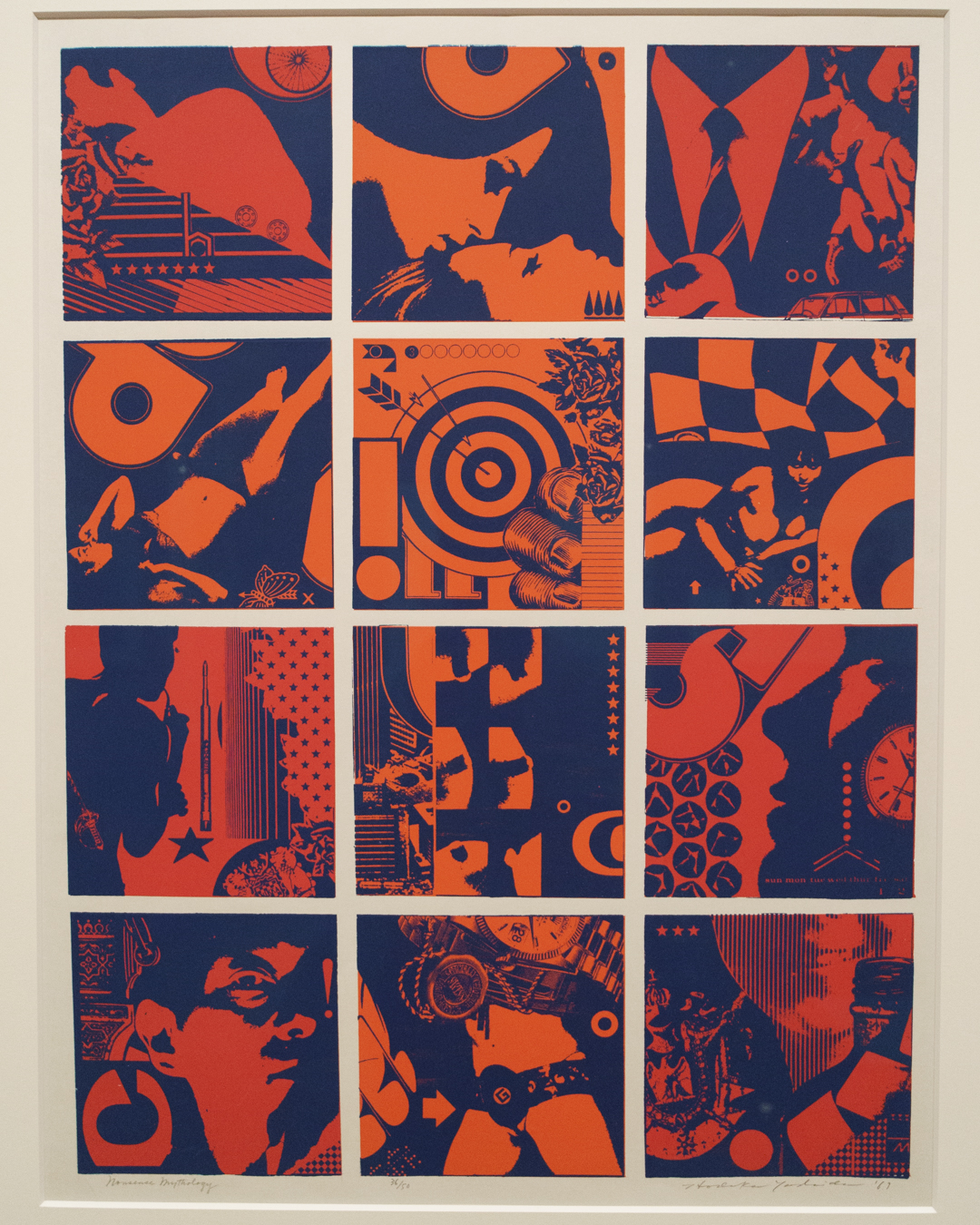

Meanwhile, the youngest son Hodaka departed from the family tradition entirely, embracing the parallel movement of sōsaku-hanga (‘creative prints’), where every aspect of production is done by the artist alone, thus prioritising their self-expression. As well as working in a radically new, dynamic visual style inspired by Western modernism and Pop Art, Hodaka also adopted additional printmaking techniques like lithography, screenprinting, and photo-engraving.

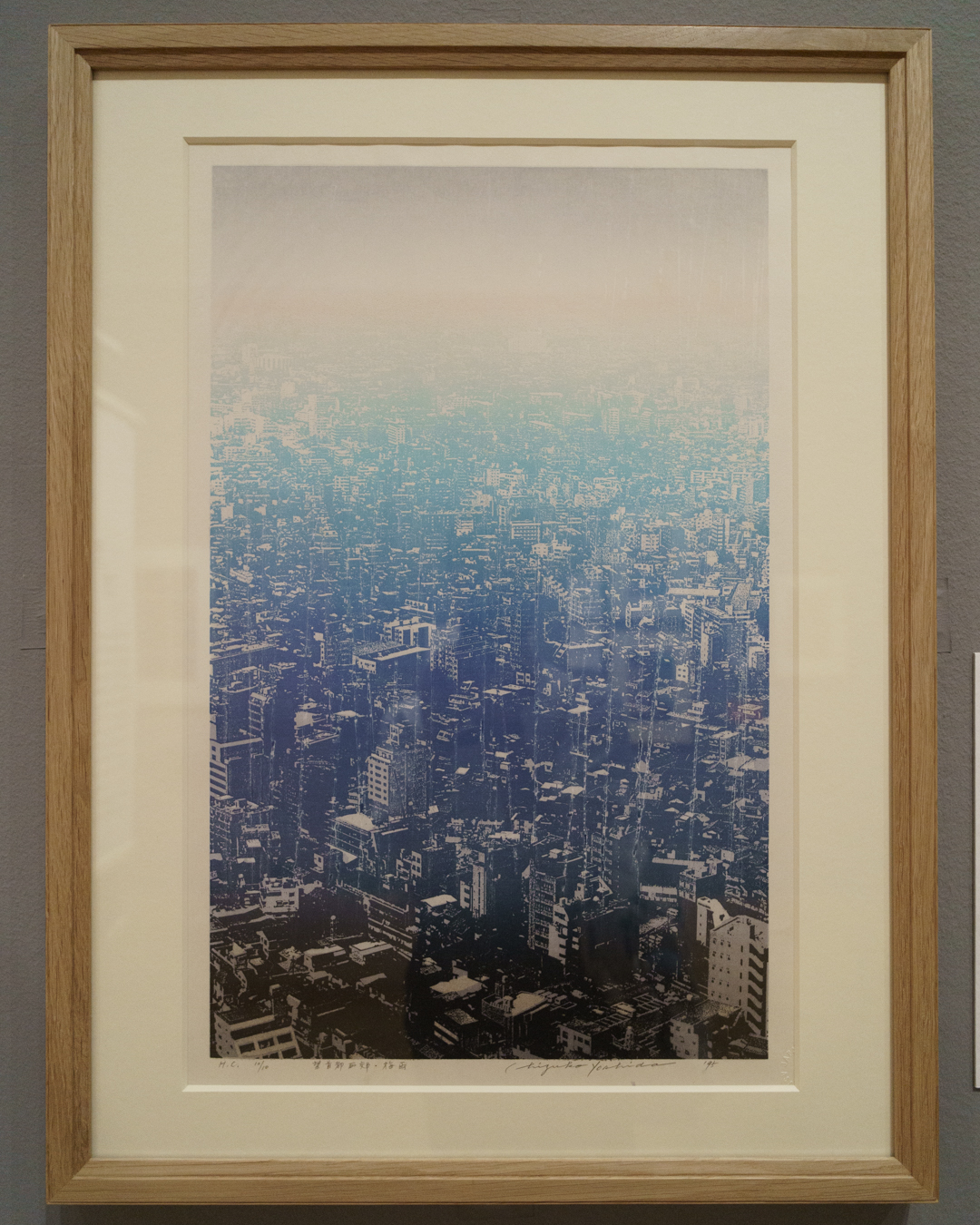

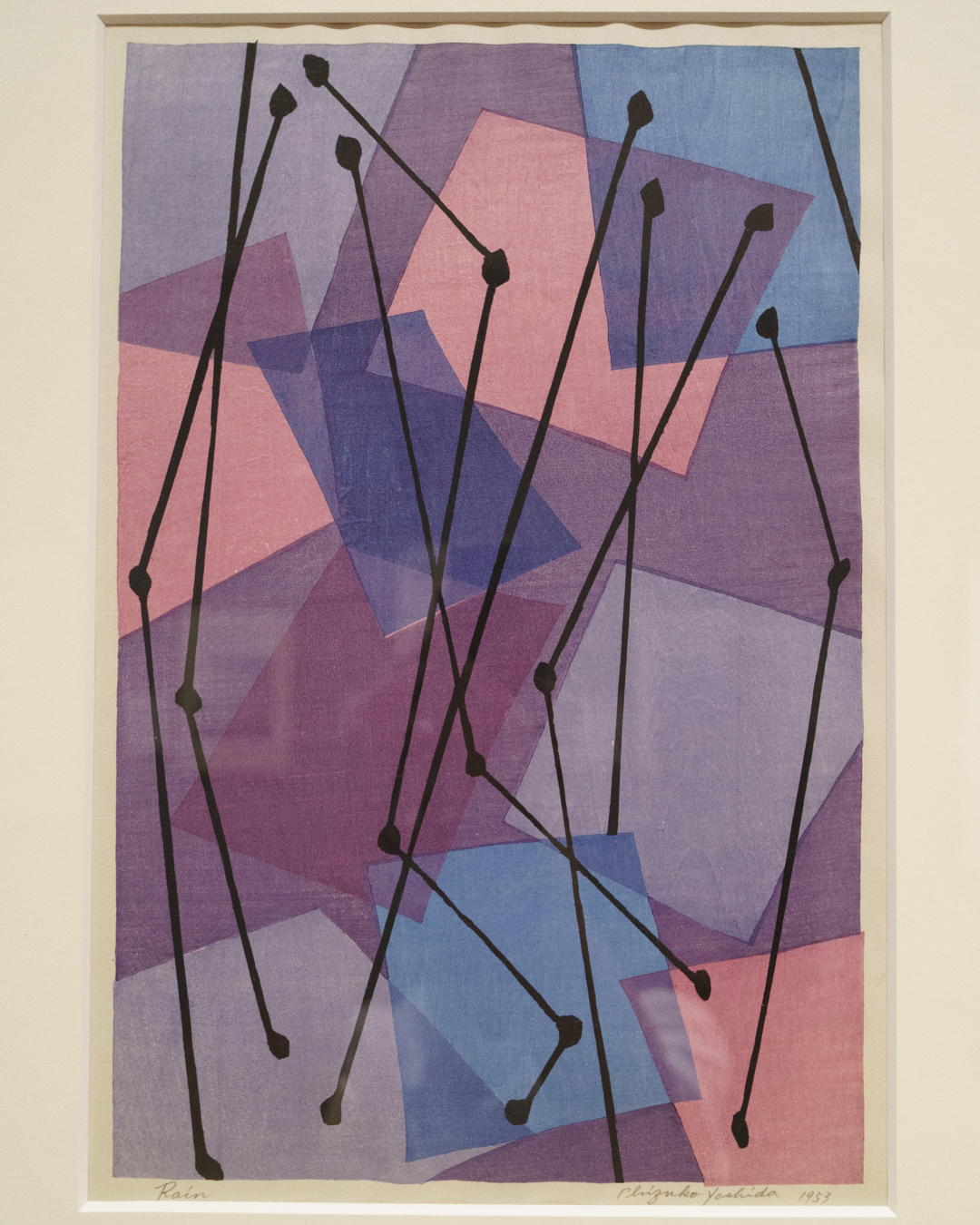

On the other hand, his wife Chizuko’s approach to woodblock prints aligns more closely with her brother-in-law, both relishing in the expressive potential of blind-stamping and abstraction. Her printing methods are particularly experimental, at times capable of producing calligraphic marks reminiscent of brushwork.

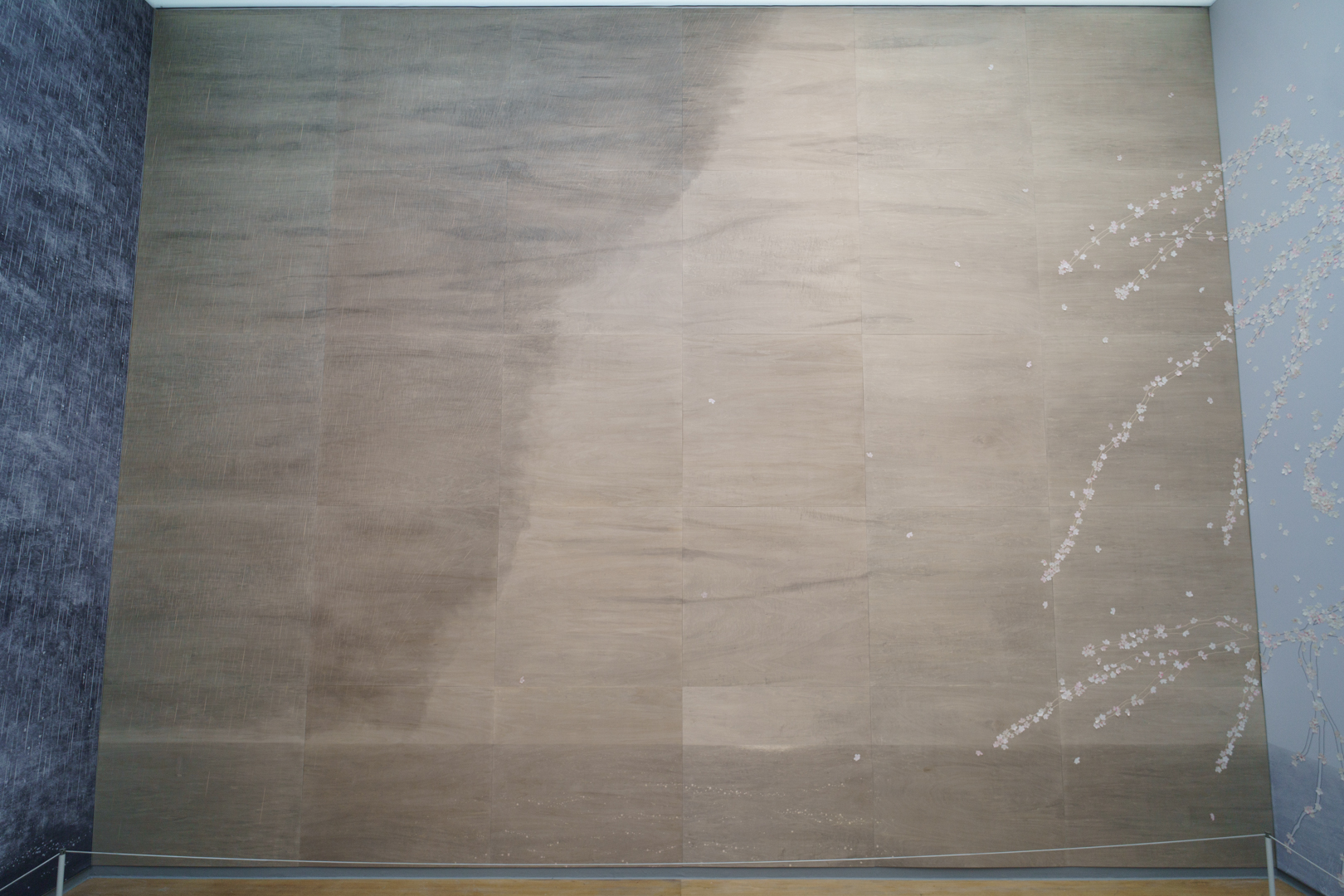

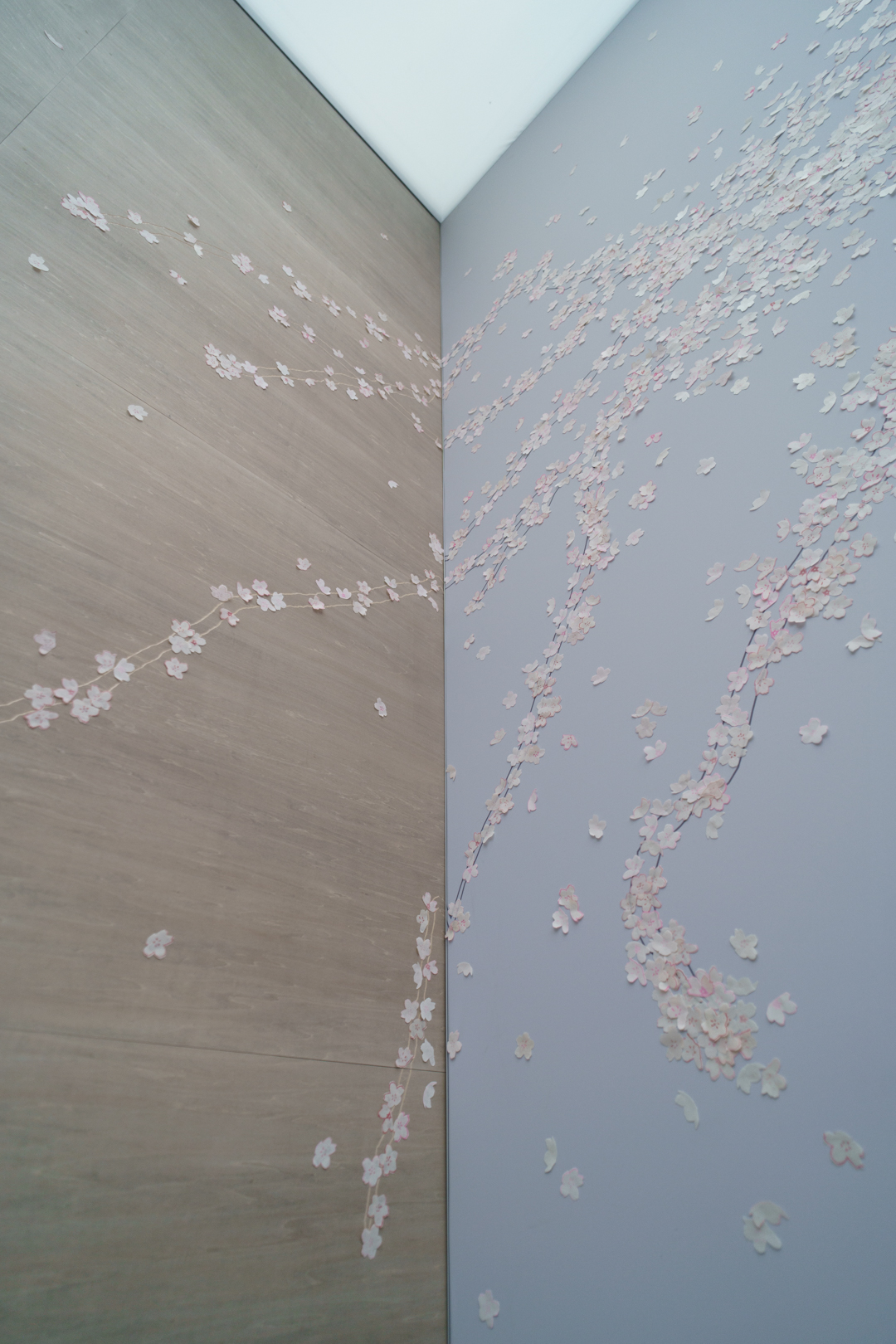

Finally, the last room is occupied by Transient Beauty (2024), a temporary, site-specific installation by Yoshida Ayomi, daughter of Hodaka and Chizuko. Inspired by her grandfather’s print Kumoi Cherry Trees (1926) in the first room, the collage of woodblock prints evokes the cherry blossom viewing experience (‘hanami’). Yet, it is also a partial lament in which the fleeting nature of the subject parallels the end of the Yoshida family of printmakers; there is currently no successor to lead a fourth generation.

This is a beautifully conceived exhibition that thoughtfully highlights each member’s contributions to the print world. That such a lineage of artists still exists is a brilliant testament to the family’s pride and devotion to the trade, and opportunities to fully assess several generations’ worth of output are rare indeed. For Western audiences, it’s a great entry point into the little-explored world of 20th-century Japanese prints.

Yoshida: Three Generations of Japanese Printmaking runs from 19 June to 3 November 2024 at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/

Leave a comment