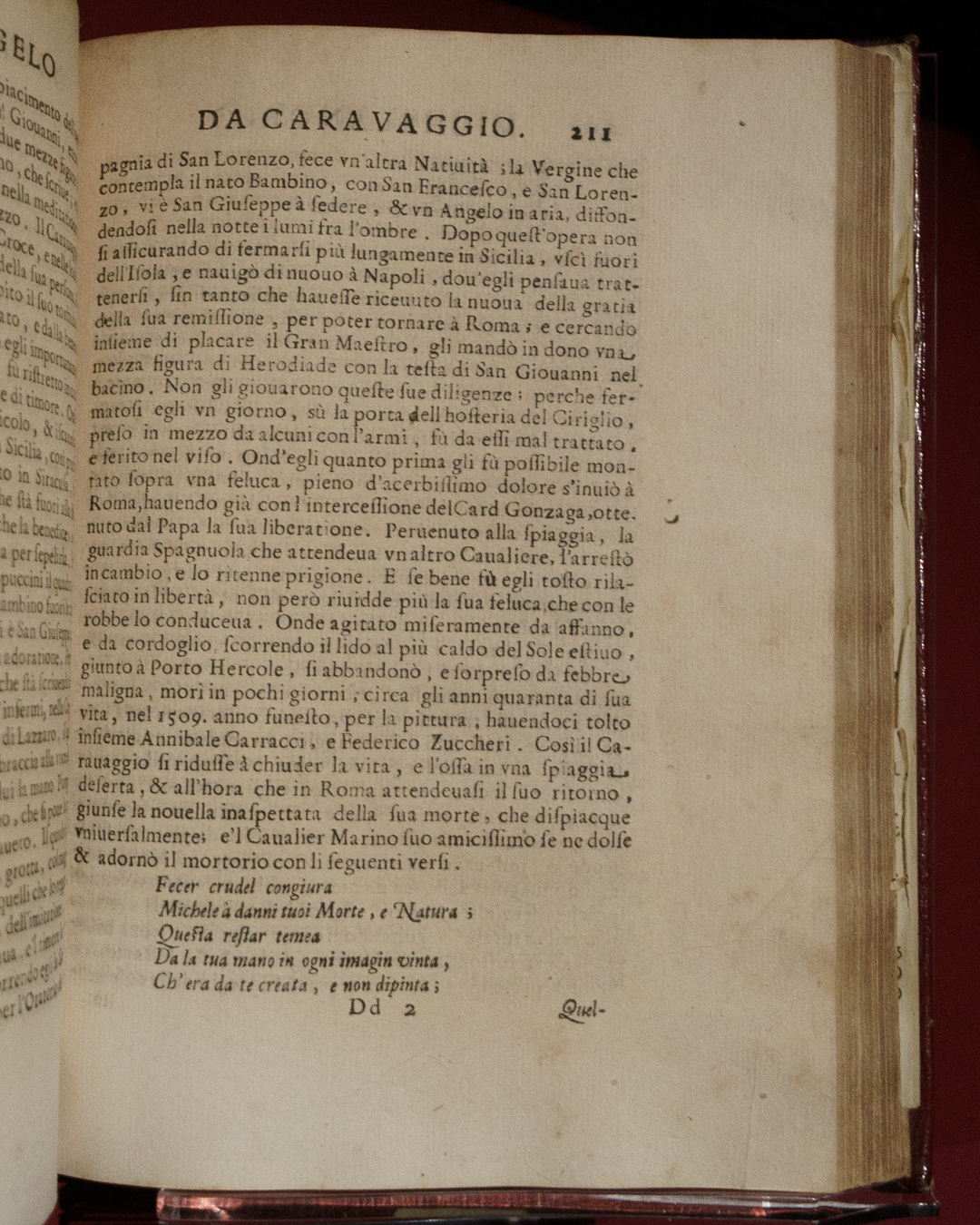

If you’ve visited the National Gallery recently, you may have noticed a curiously long queue extending from a small, unassuming room all the way to the staircase with the Bridget Riley installation. This is The Last Caravaggio, a free display containing just two paintings and three textual sources.

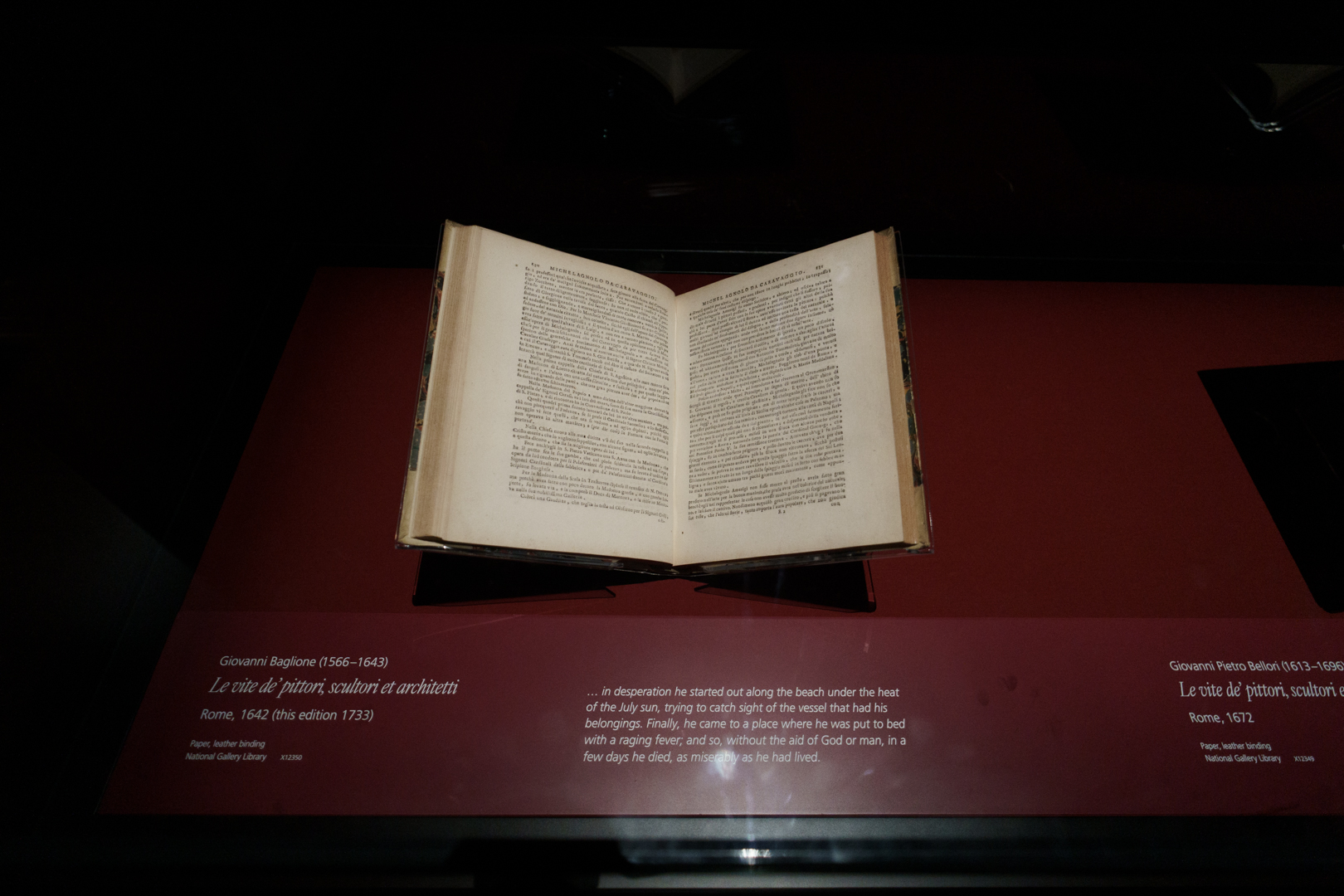

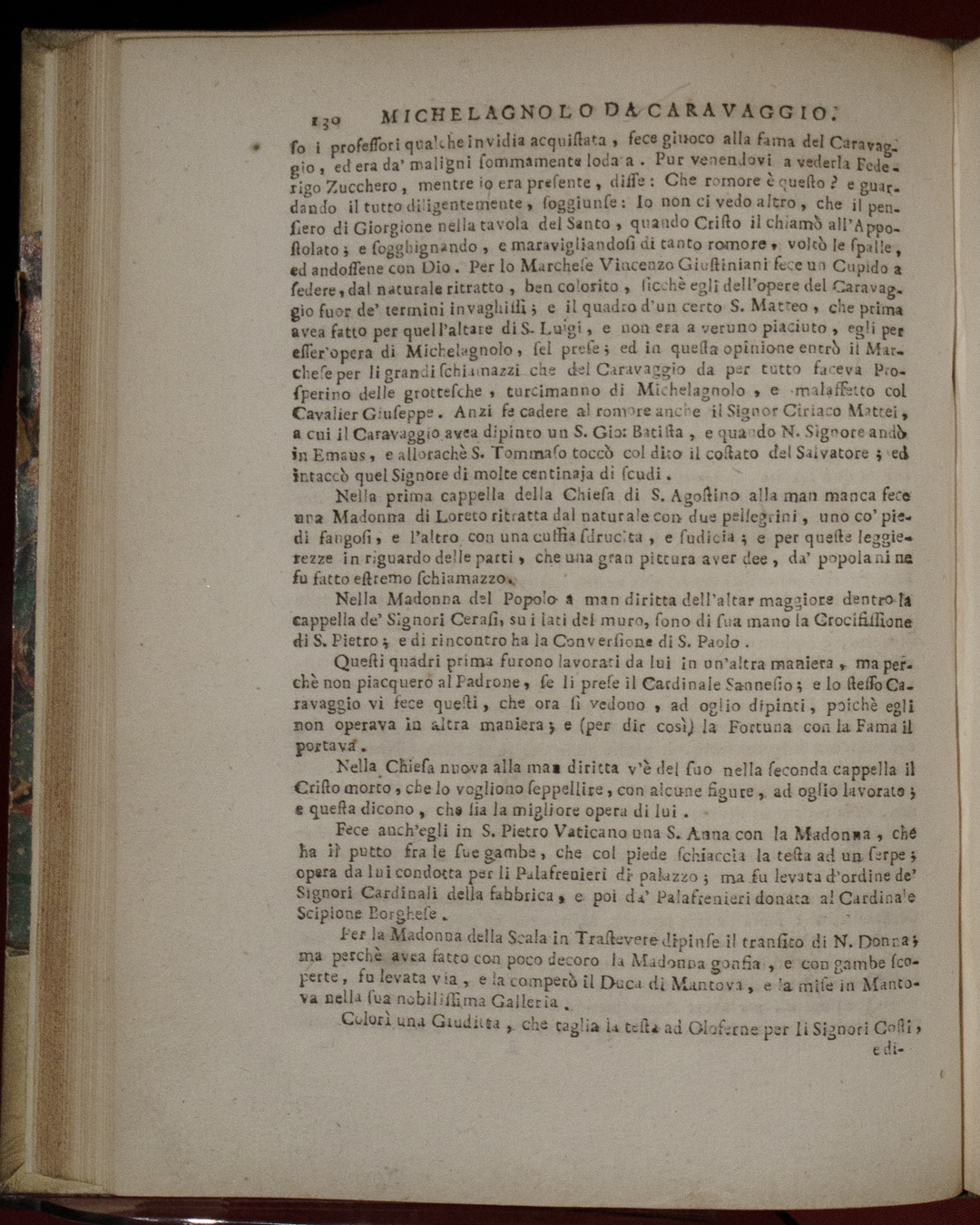

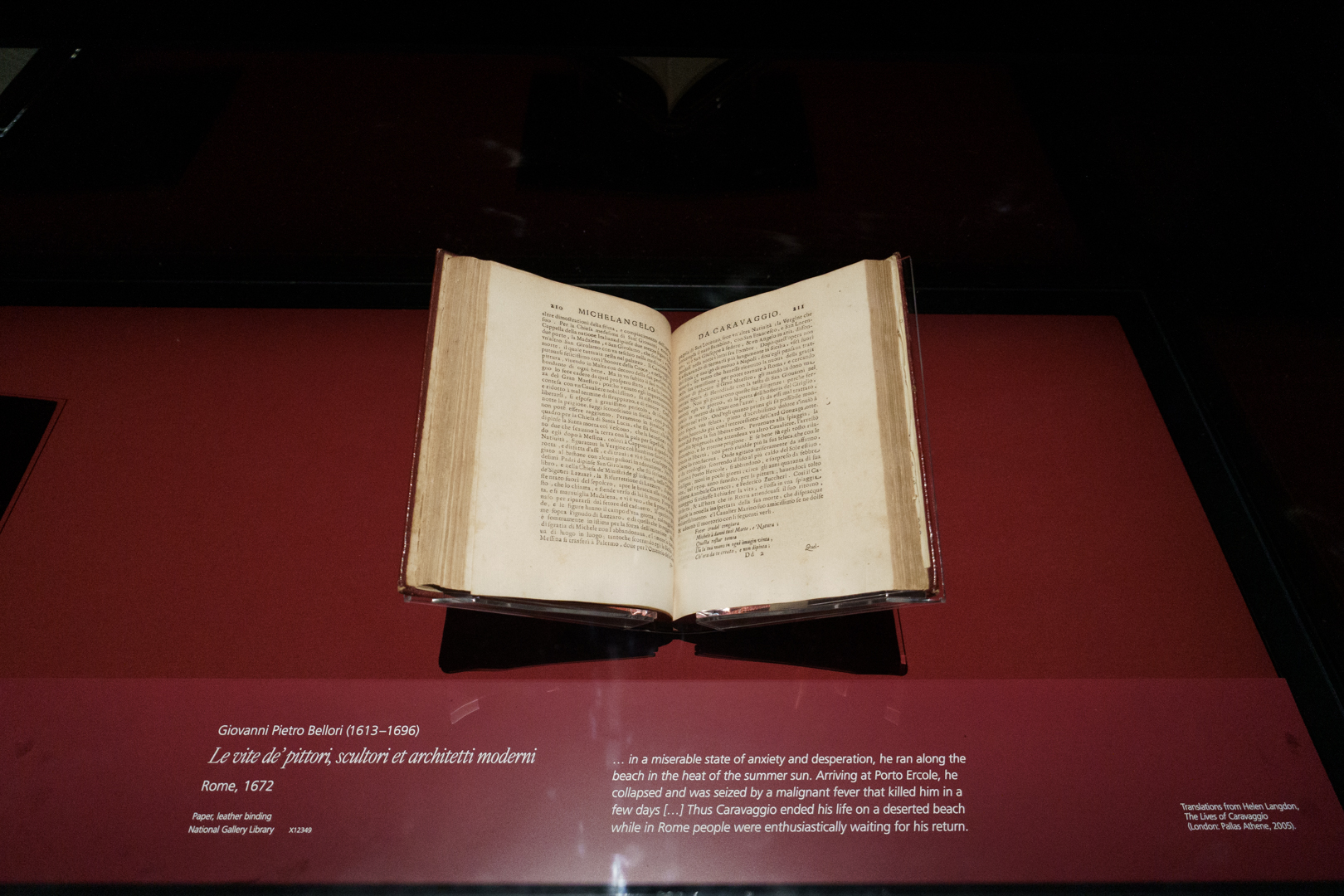

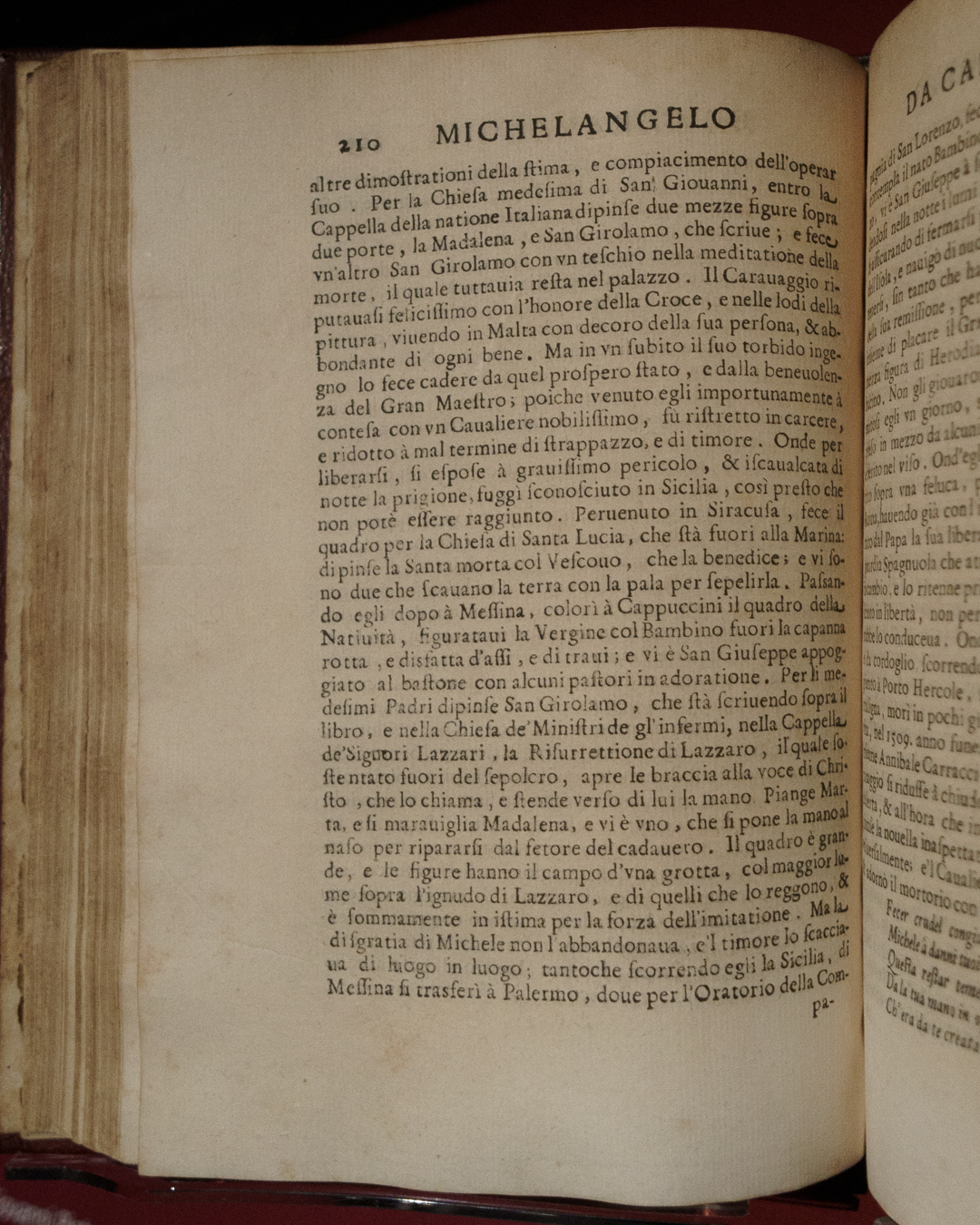

The star of the show is The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula from the Intesa Sanpaolo Collection (Gallerie d’Italia, Naples). Completed in May 1610, it is the artist’s last documented painting, possibly the last one he ever made. According to two contemporary biographers, Giovanni Baglione and Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Caravaggio landed on a beach in Porto Ercole on his way back to Rome, eventually losing his life to a fever in July that same year; both accounts are on display in the exhibition.

Accompanying Caravaggio’s last painting is the National Gallery’s own Salome Receives the Head of John the Baptist, another late work from about 1609 onwards. Collectively, they demonstrate his use of heavy chiaroscuro and powerful storytelling, particularly his treatment of violence, which he had personal experience throughout his life. In 1606, Caravaggio was forced to flee Naples because he had murdered Ranuccio Tommasoni (a pimp) over a bet in a tennis game; specific reasons remain unclear.

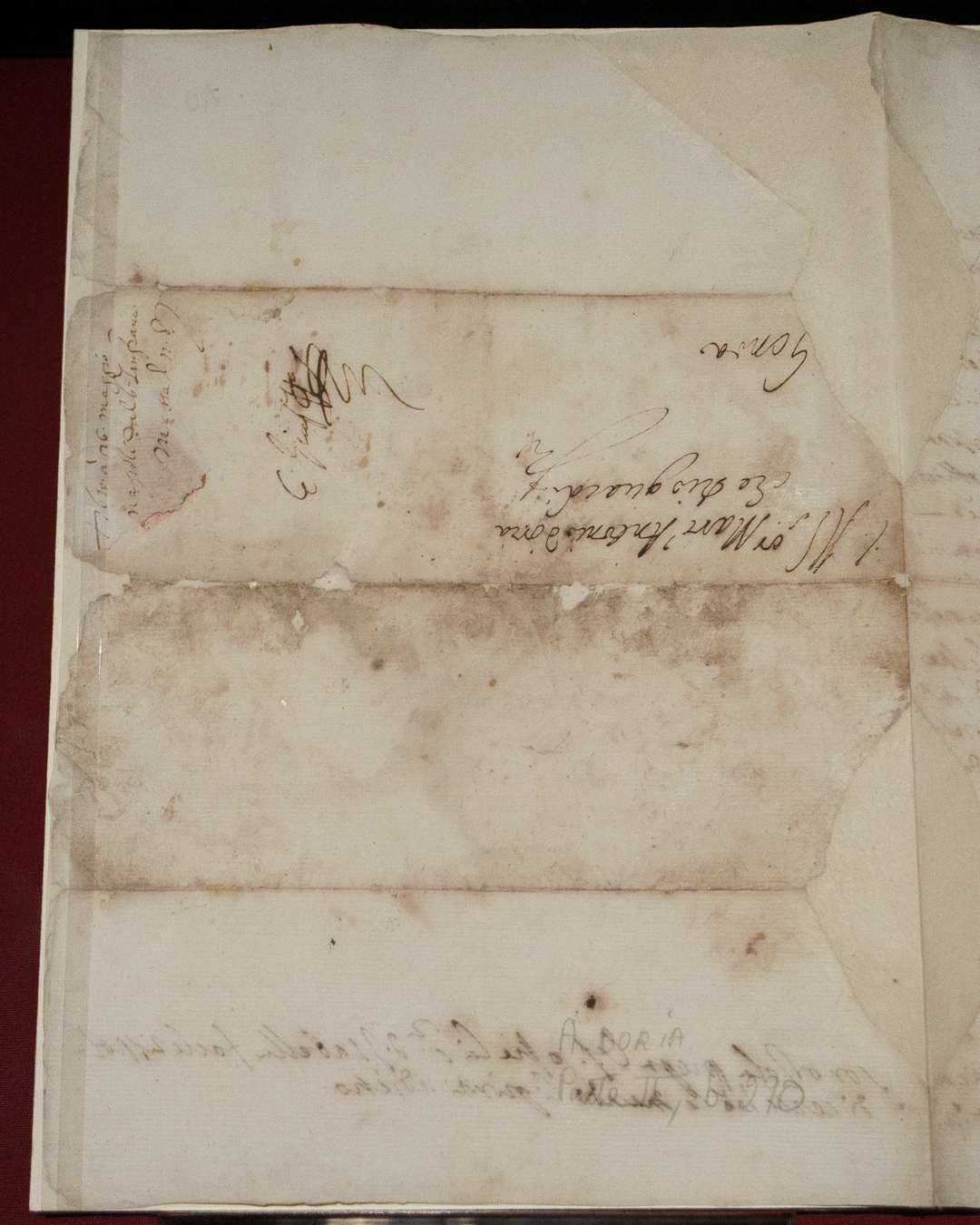

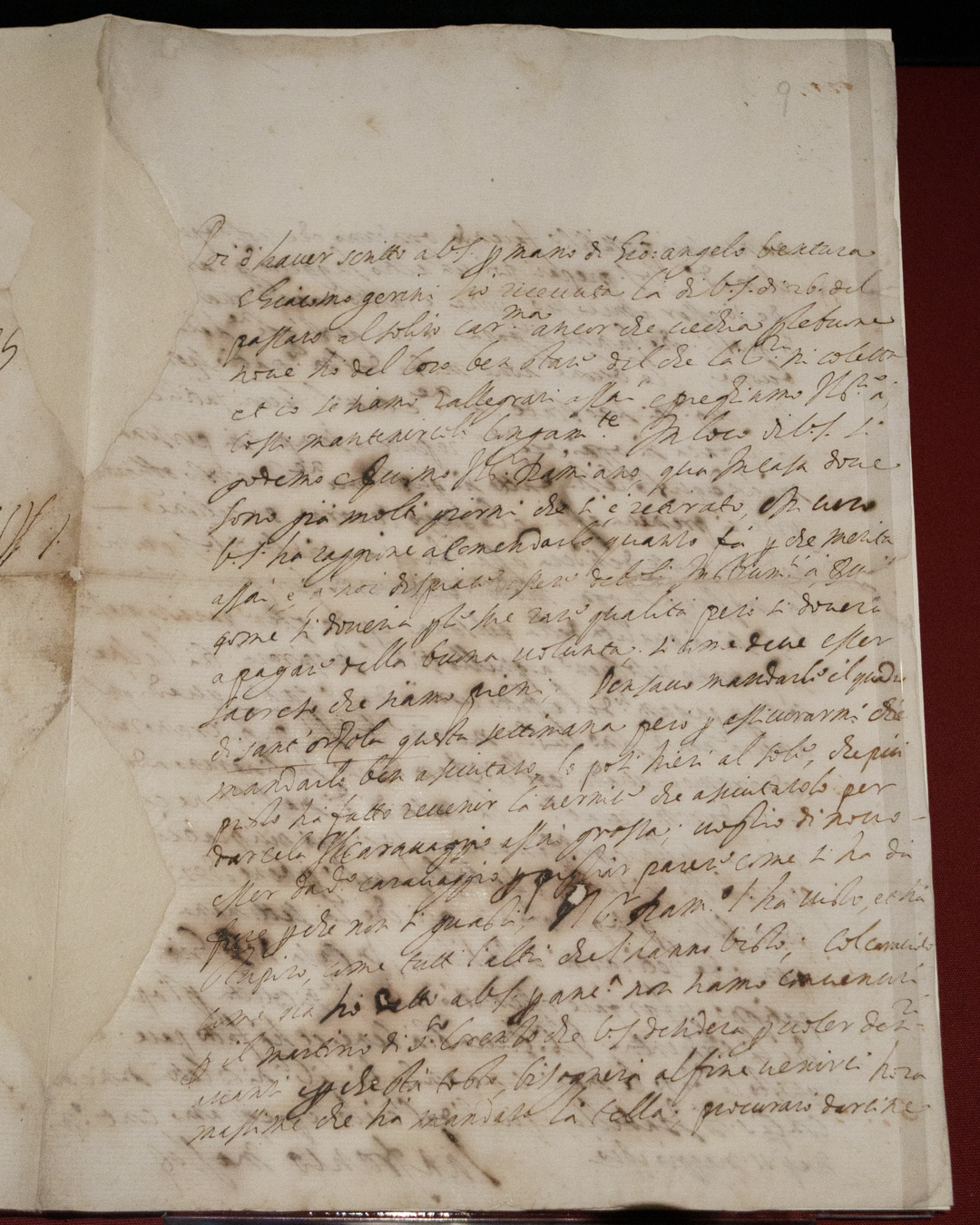

Yet, for a long time, it was believed to have been painted by one of Caravaggio’s followers. This is where a crucial piece of evidence comes into play, a handwritten letter (dated 11 May 1610) to the Genoese nobleman Marcantonio Doria (who commissioned the painting) from his business agent in Naples, Lanfranco Massa. Discovered in 1980 and on display in the UK for the first time, the letter explicitly mentions Caravaggio’s participation in the work:

‘I had intended to send you the picture of Saint Ursula this week, but to make sure of sending it perfectly dry I put it out yesterday in the sun, which, rather than drying out the varnish, made it soften, since Caravaggio applied it quite thickly; I will go round to the said Caravaggio’s again to get his opinion on what to do so I can be sure of not ruining it; Signor Damiano has seen it, and was amazed, like everyone else who has seen it.’

For the Martyrdom, Caravaggio departed from Saint Ursula’s traditional depictions, opting to portray instead the moment she is shot with an arrow by the king of the Huns, whom she refused to marry because he did not share her Christian faith. Meanwhile, the artist himself helplessly peers over the saint’s shoulder. Rather than showing us the gore and bloodiness of this graphic act of violence, Caravaggio has left it to our imagination, giving us a weirdly graceful depiction of the scene instead. A similar approach underpins the Salome painting.

While both paintings are difficult to compare in the room, this focused exhibition offers some nice, sensationalist context to Caravaggio’s final months. Quite fitting for one of art history’s famous ‘bad boys’, I think.

The Last Caravaggio runs from 18 April to 21 July 2024 at the National Gallery, London, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/

Leave a comment