Entangled Pasts, 1768 – now is an apologetic dive into the Royal Academy of Arts’ past cultural contributions to Britain’s colonial history, mainly via its promotion of desirable artistic values and themes.

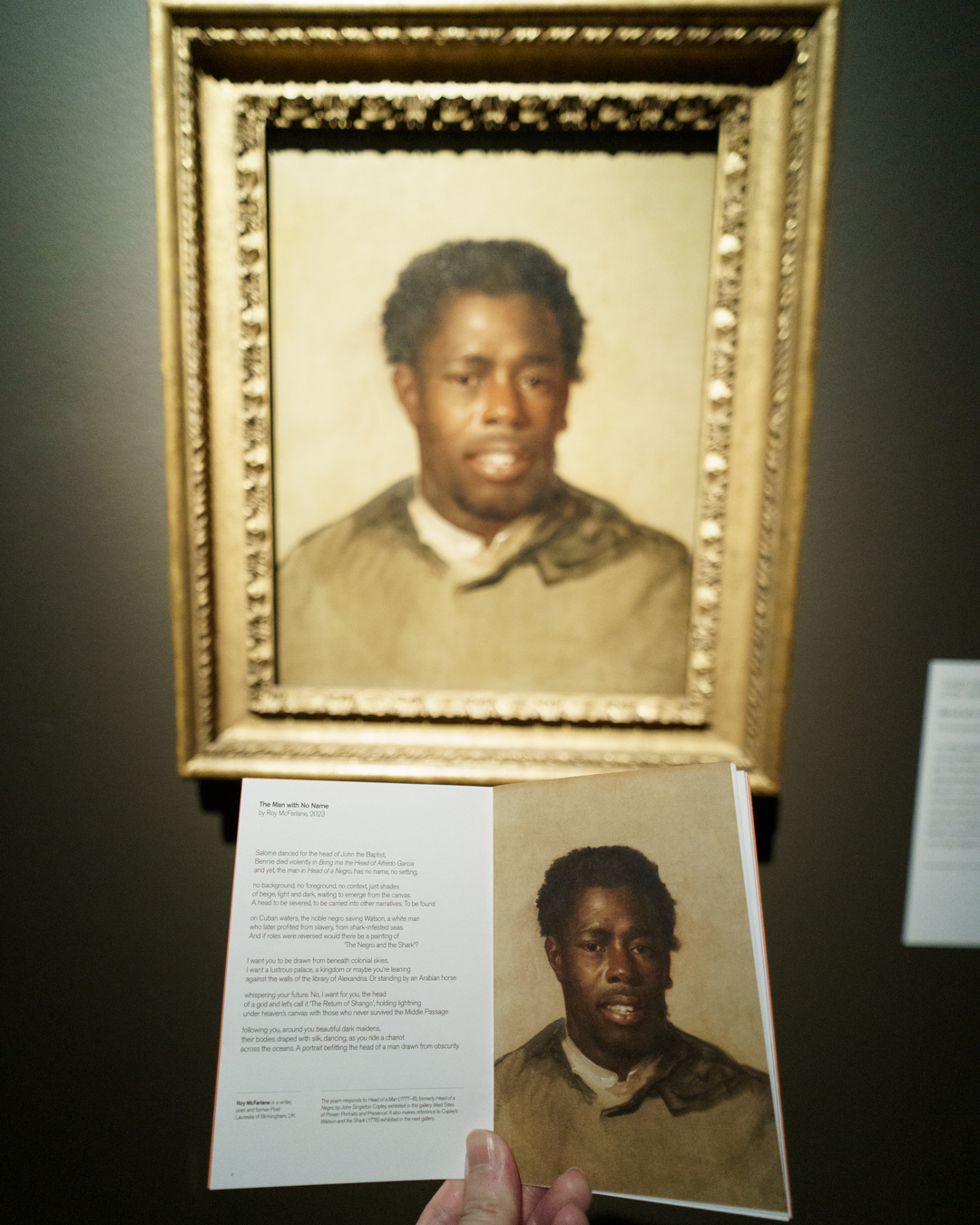

Although the topic is particularly dense, the exhibition is surprisingly light and palatable; captions sometimes felt a bit too sparse, particularly for impressive-looking works like Yinka Shonibare’s Woman Looking Up. The first few rooms elegantly address core issues head on: portraits of lost Black identities, coloured models painted in subservient roles, and imperialist subject matter with martyrdom vibes, all painted by esteemed Royal Academicians like Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.

Emerging from the pictorial cloud of unknown sitters in the first room is Ignatius Sancho, the first man of African descent to vote in a British election. His letters were one of the earliest English accounts of African slavery written by a former slave. At the bottom of one of his letters to William Stevenson, dated 1 April 1779, he wrote:

‘I am Sir an Affrican – with two ffs – if you please – & proud am I to be of a country that knows no politicians – nor lawyers – […] –nor thieves of any denomination save Natural….’

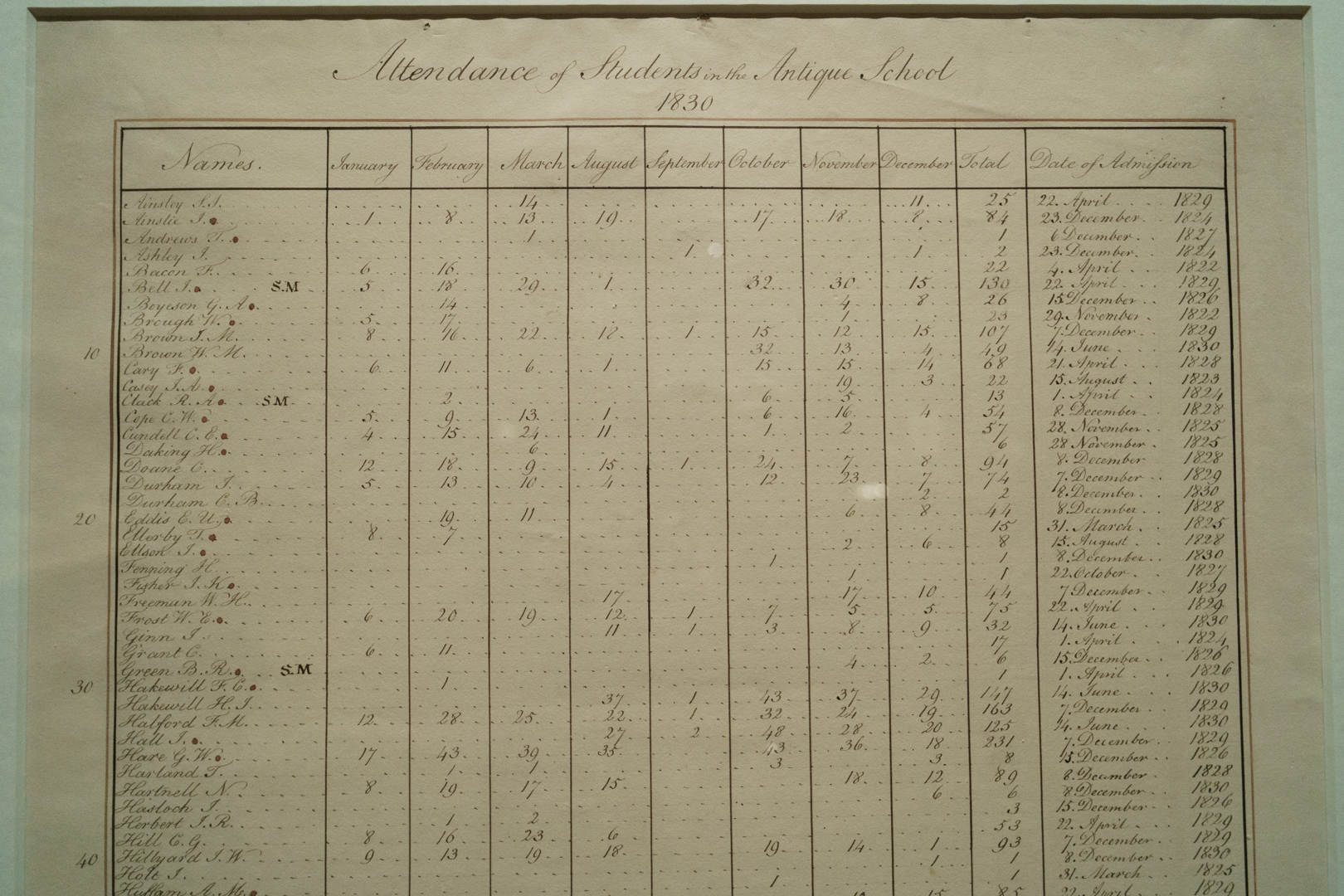

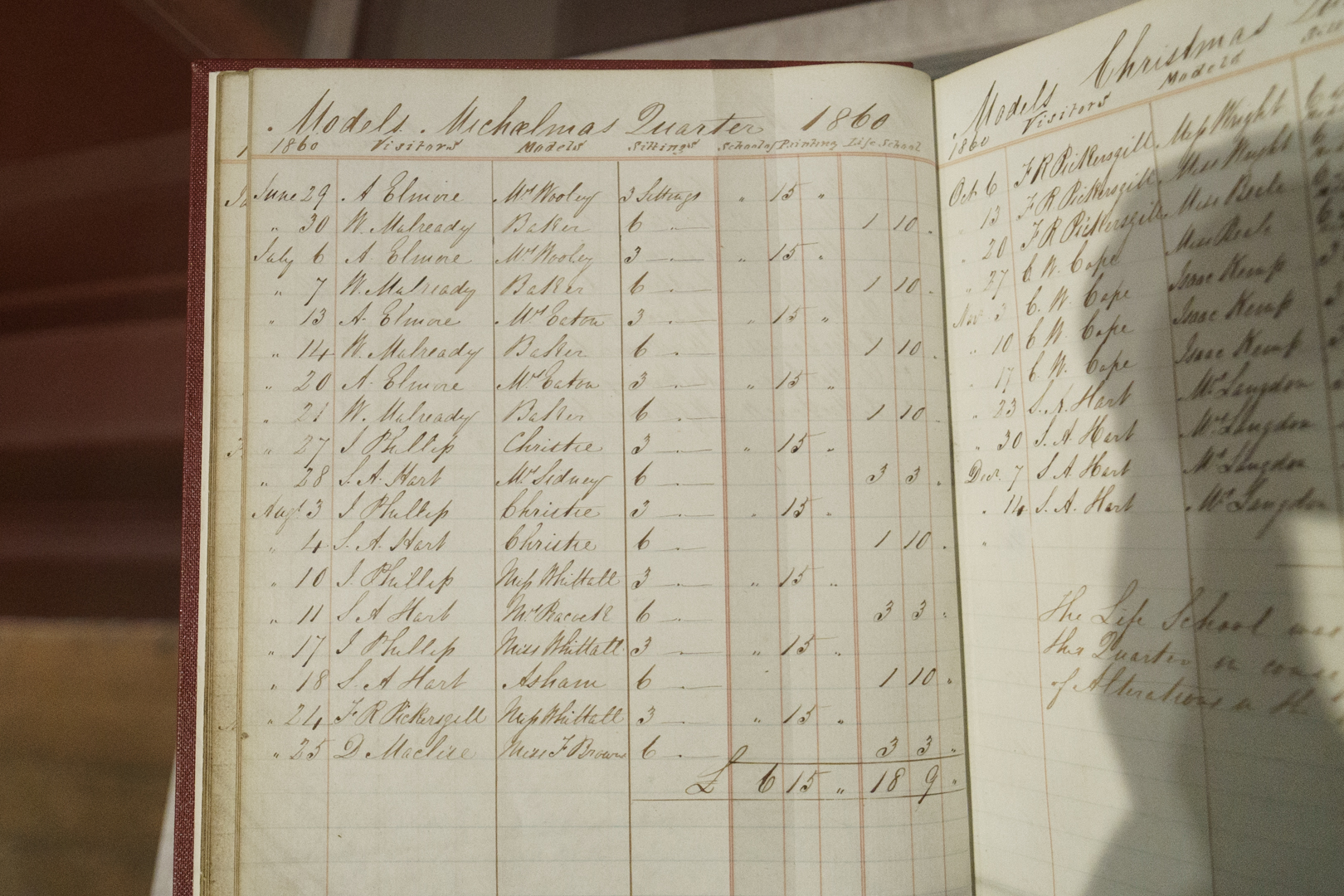

There’s very little that you wouldn’t expect from a show like this – portraits of slave owners, Arcadian scenes of plantation life – yet we do find some interesting progressive turning points concerning the Academy itself. In my favourite room by far, the earliest date of admission of a Black student, William Morrison Brown (9th line), into the Royal Academy Schools is recorded on 14 June 1830, while a corner dedicated to Pre-Raphaelite model Fanny Eaton documents her 2-hour life modelling sessions in the RA schools (5th and 7th lines as ‘Ms Eaton’) for a fee of 15 shillings in 1860. A full circle moment happens at the end of the show, where recent RA Schools graduate Olu Oguunaike’s I’d Rather Stand, referencing the Fourth Plinth, is proudly shown with Shonibare’s Justice For All.

Edwin Longsden Long’s massive The Babylonian Marriage Market is also just a marvellously executed painting despite its disheartening subject matter; the racialised hierarchy of skin tones in the line of soon-to-be brides just hits home, especially paired with Keith Piper’s contemporary parody The Coloureds’ Codex, An Overseers’ Guide to Comparative Complexion, a pigment box documenting the skin tones of people involved in the slave trade.

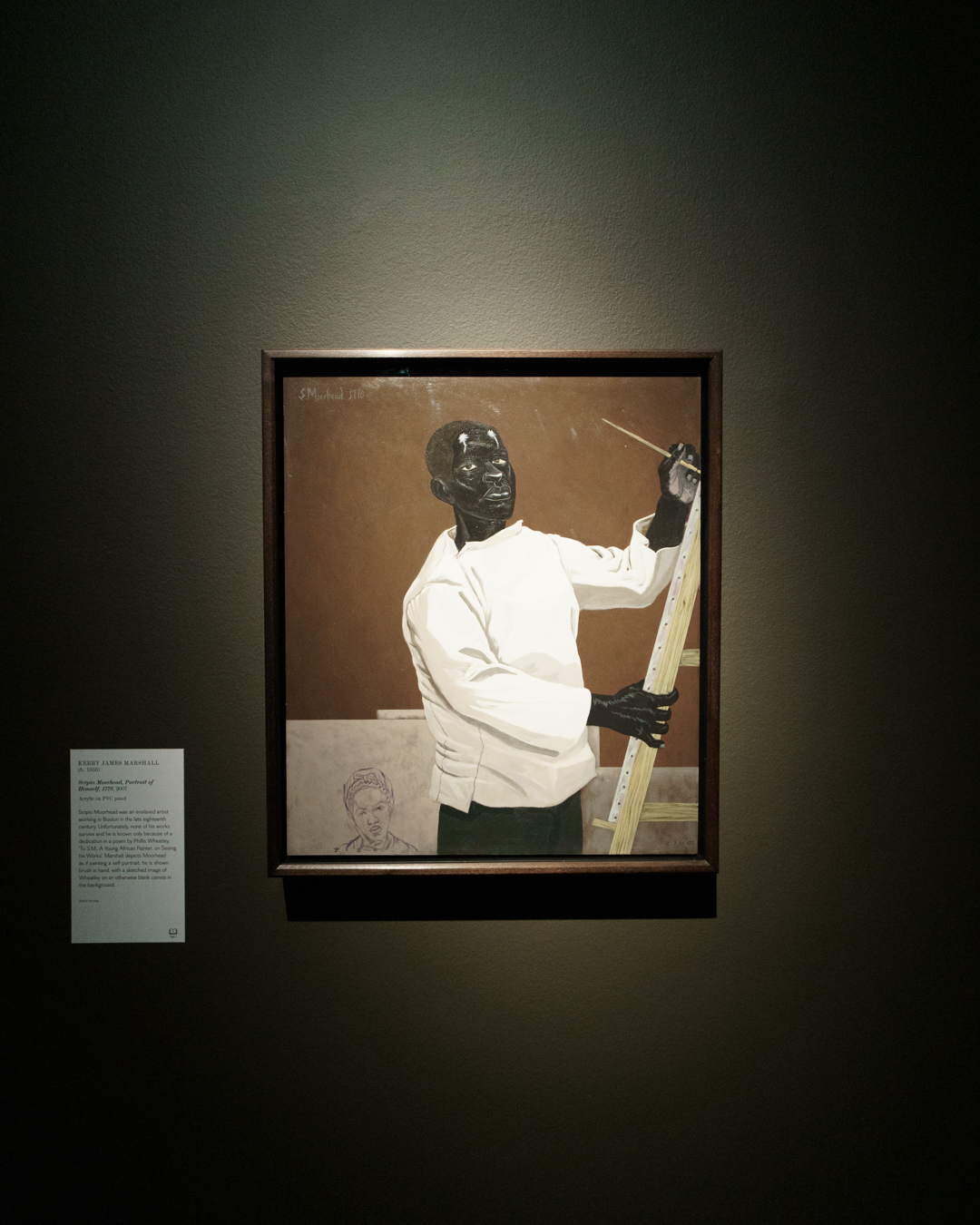

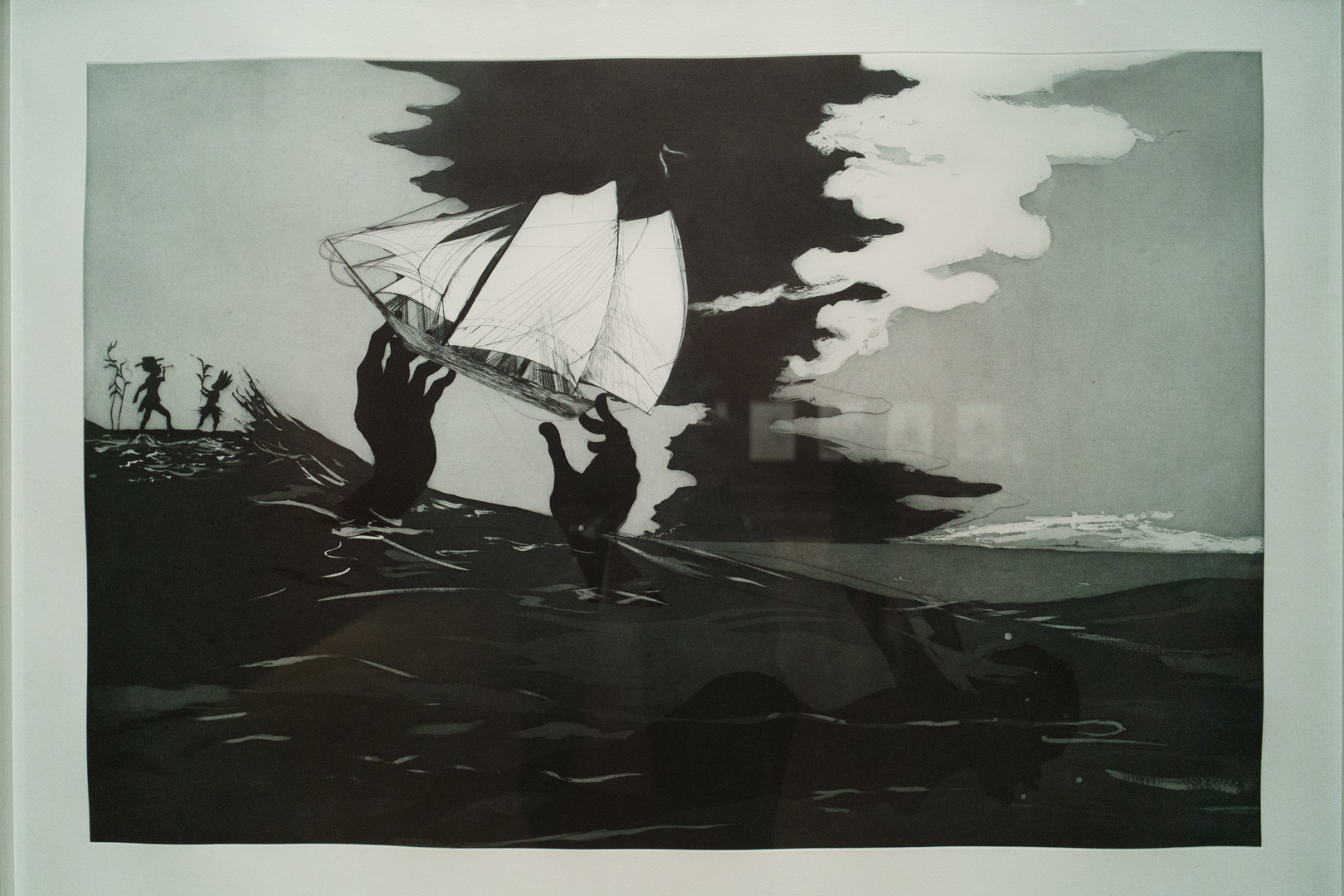

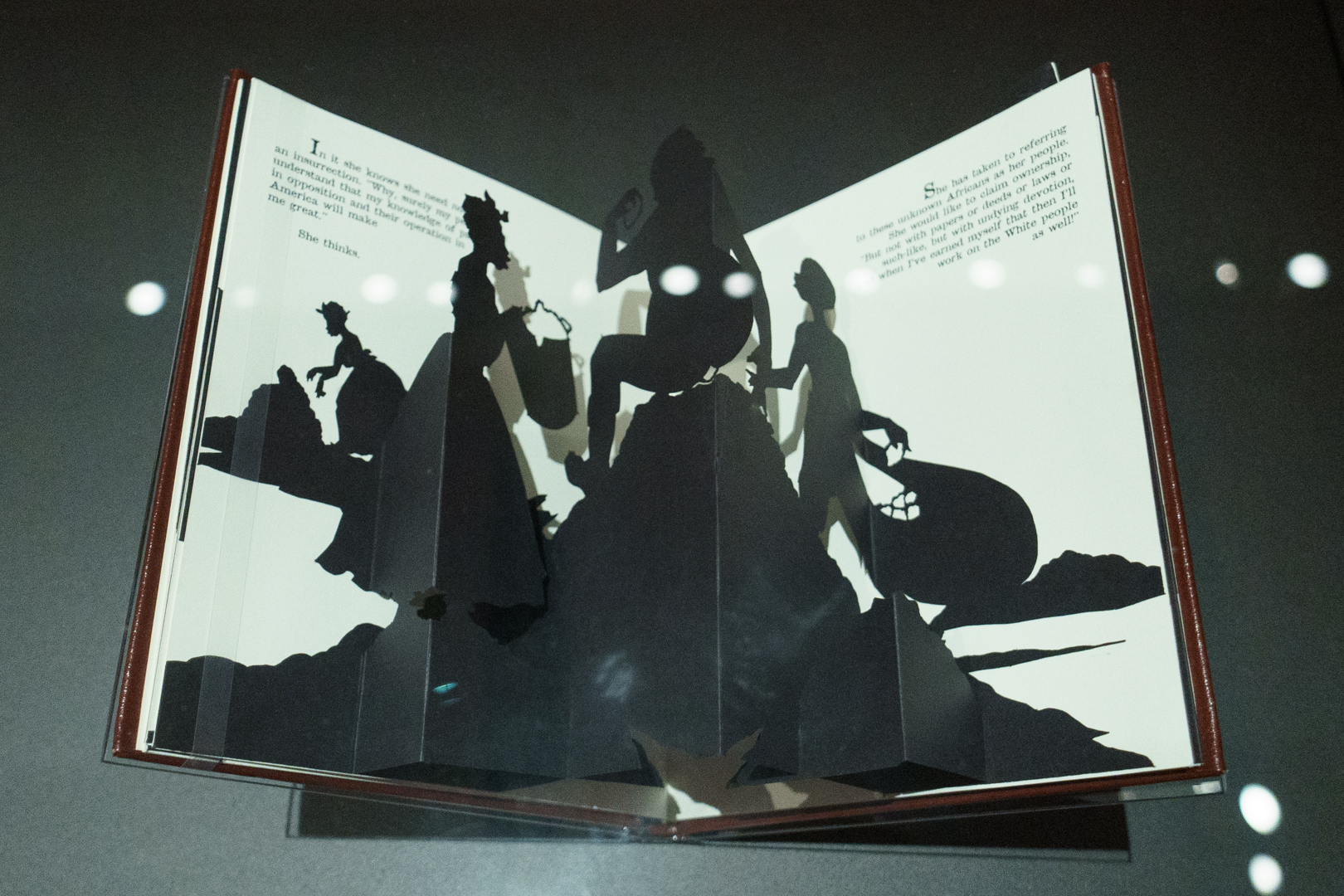

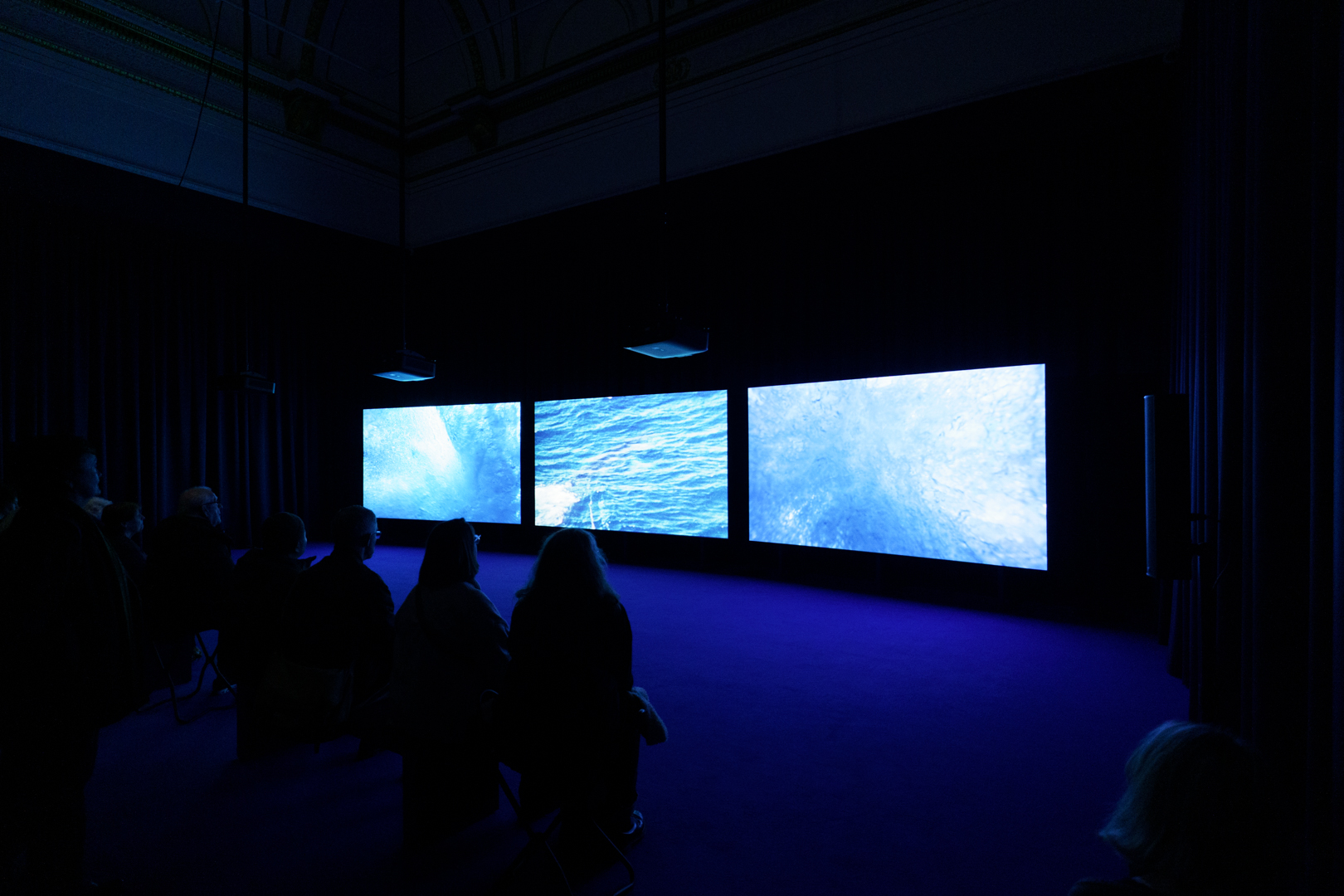

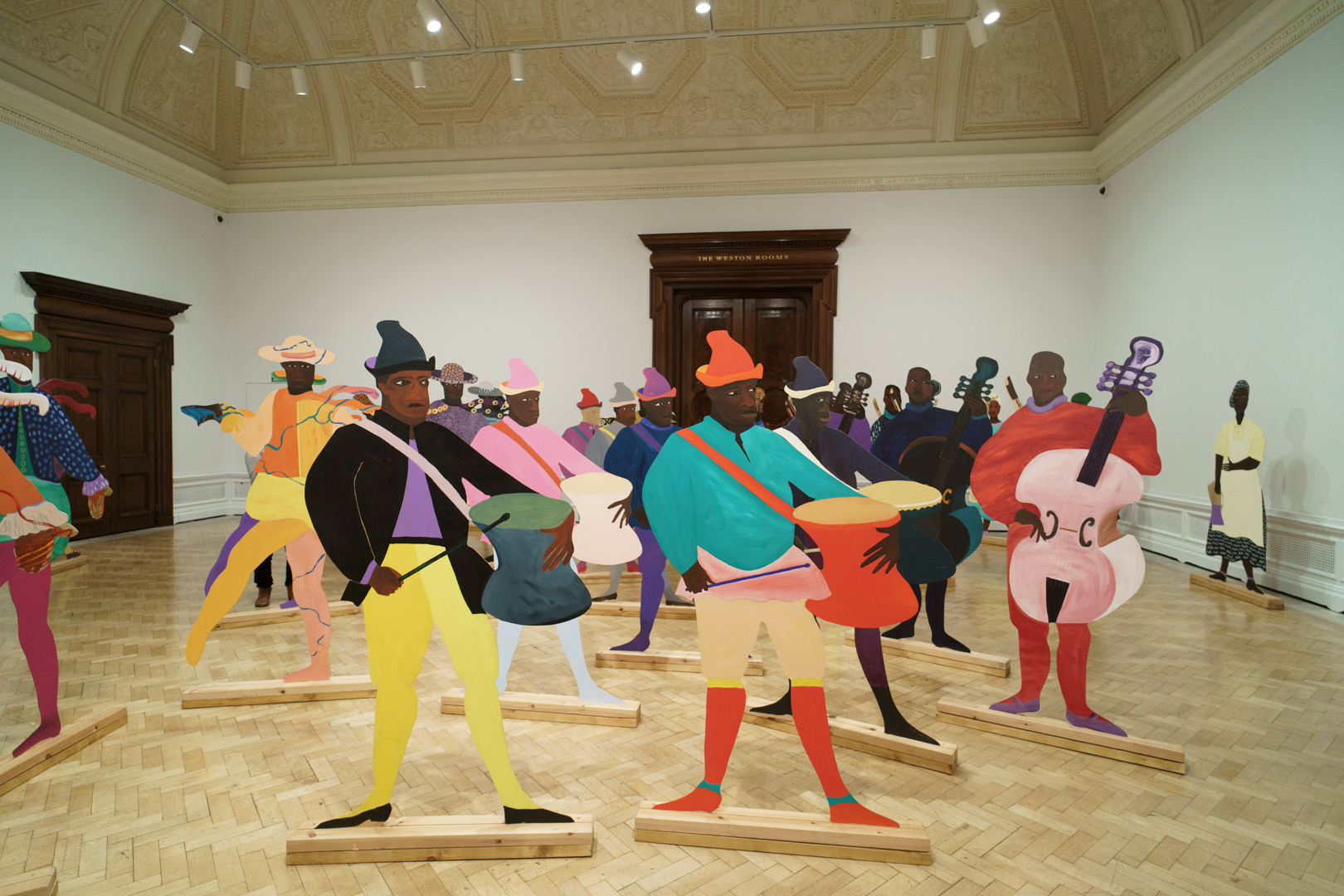

The contemporary interventions responding to this wealth of historical material really do bring it all together, emphasising how much has changed since the 18th century but also what problems have remained. Hew Locke’s Armada invades the second room, Kehinde Wiley gives Black sitters authority and power in his portraits, Kara Walker muses on Britain’s imperialism, Isaac Julien pays homage to the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, Barbara Walker draws attention to Black models in Old Master paintings, El Anatsui explores drowned migrants crossing the sea, and Lubaina Himid gives a voice to underappreciated workers in society.

If there is one unmissable work to see, it is Betye Saar’s I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break, an ironing board bearing the famous diagram of the 18th-century British slave ship Brookes, with an iron shackled to the board, and a white, ‘KKK’-embroidered sheet hanging behind it.

This is a must-see exhibition, one that’s been long overdue and rightfully part of a national open letter admitting that British institutions and individuals did wrong in the past, and are open to progressive change in the modern age. A phenomenal effort.

Entangled Pasts, 1768 – now: Art, Colonialism and Change runs from 3 February to 28 April 2024 at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/

Leave a comment