A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography at Tate Modern starts off strong: a procession of Nigerian monarchs photographed by George Osodi; Zohra Opoku’s massive fabric piece commenting on globalisation; and Kudzanai Chiurai’s photographic series reinterpreting Christian themes that could parallel Beyoncé’s Renaissance tour. This show of strength and vulnerability immediately forces us to reconcile with the continent’s troubled colonial past and its present rejuvenation.

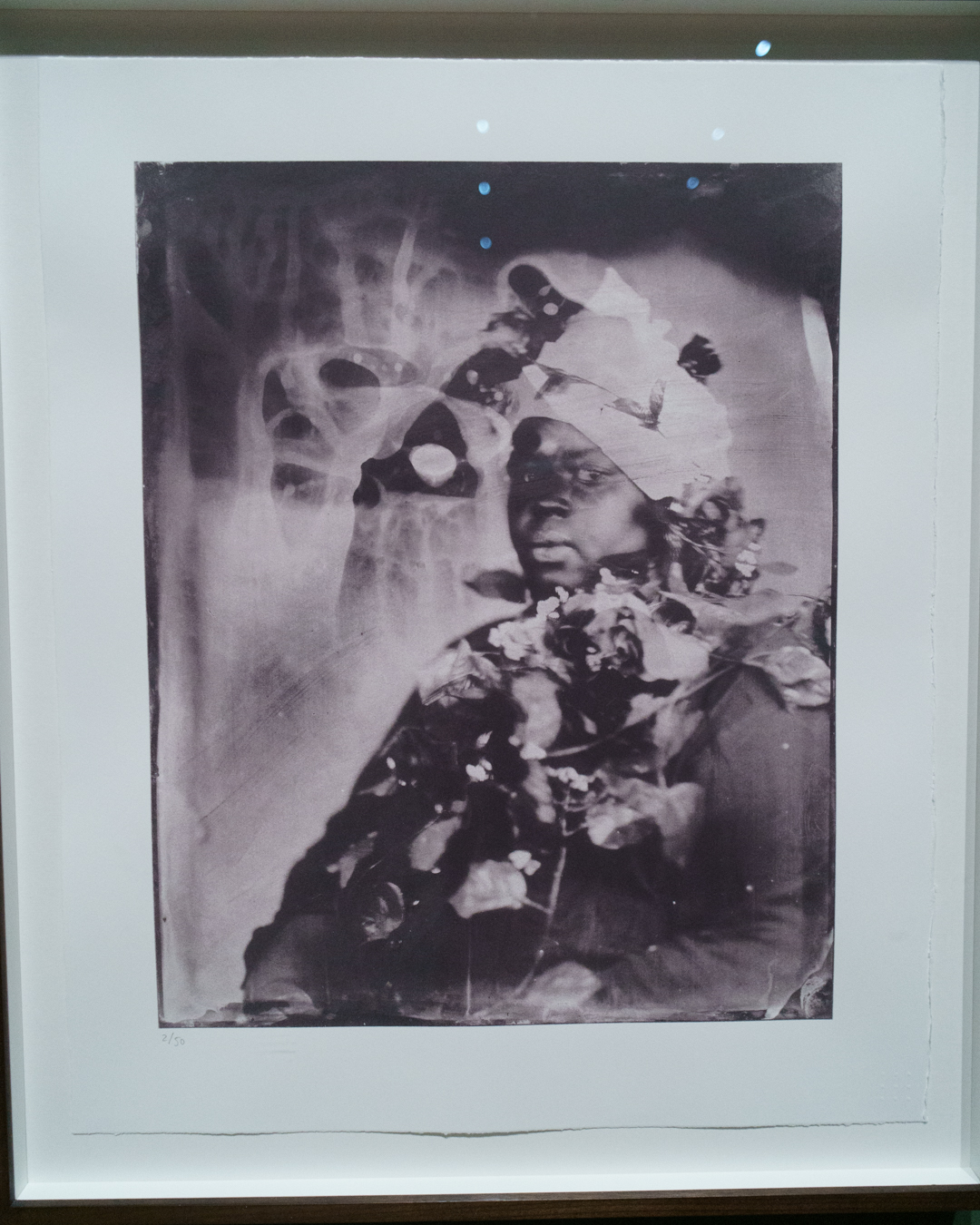

In later rooms, we are enchanted by the spiritualism and ritualistic practices that we have come to associate with African culture, such as those practised by the Yoruba people of Nigeria. Using masks and performances, the artists engage their ancestors in a process of renewal and reclamation in a post-colonial age.

Impressed on me was Edson Chagas’ Tipo Passe series, passport-style photographs of sitters wearing traditional Bantu masks and contemporary clothing, essentially reactivating the spirits of ancestors after a long slumber as cultural artefacts for passive display rather than use in active rituals.

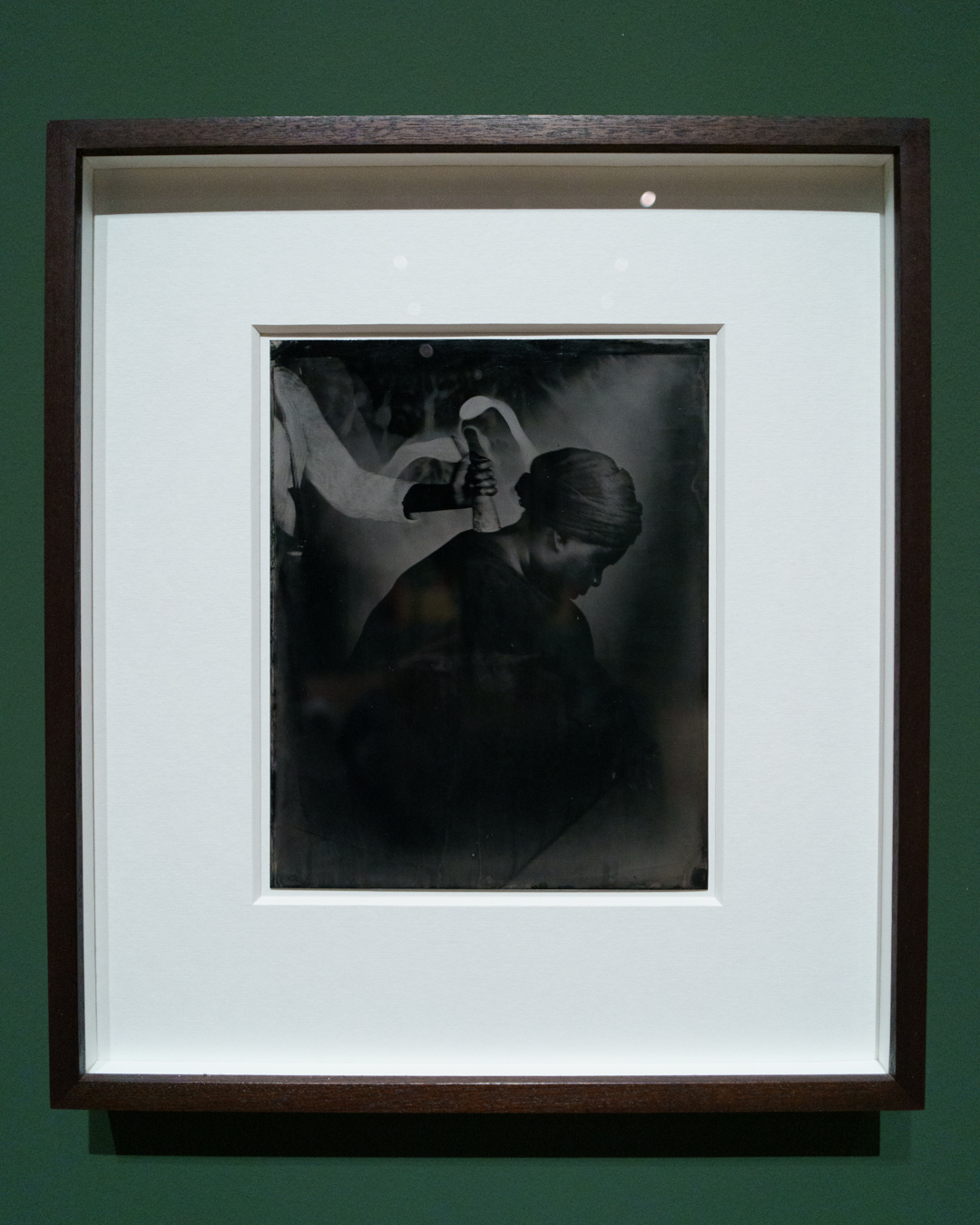

Unfortunately, some artists have been lost to us too soon, mainly Khadija Saye whose wet-plate collodion self-portraits adorn a single wall; she died in the Grenfell Tower Fire in 2017 and is currently memorialised in Chris Ofili’s mural Requiem at Tate Britain’s North Staircase. The two artists met in May that year when both were exhibiting at the Venice Biennale, a month before her tragic death.

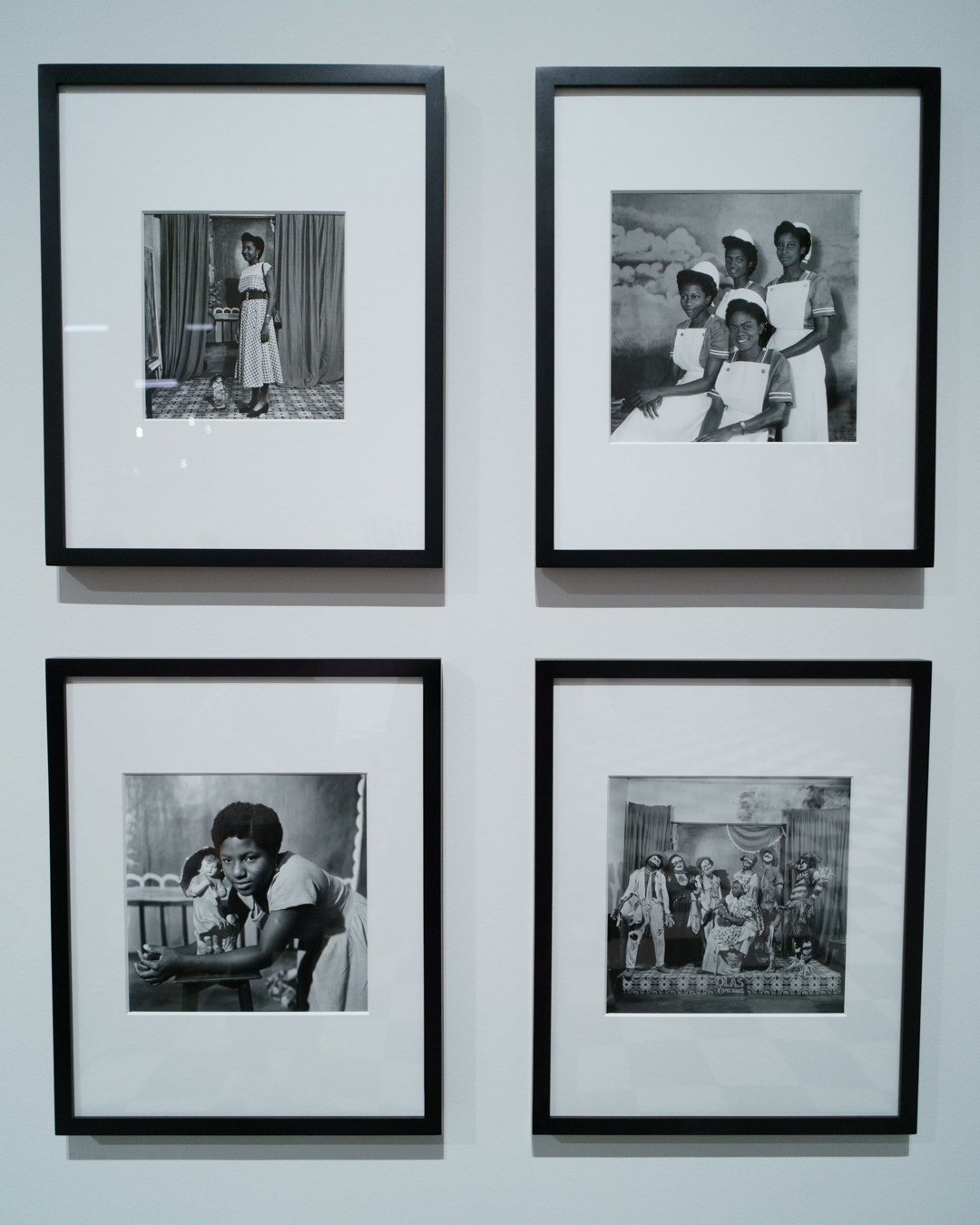

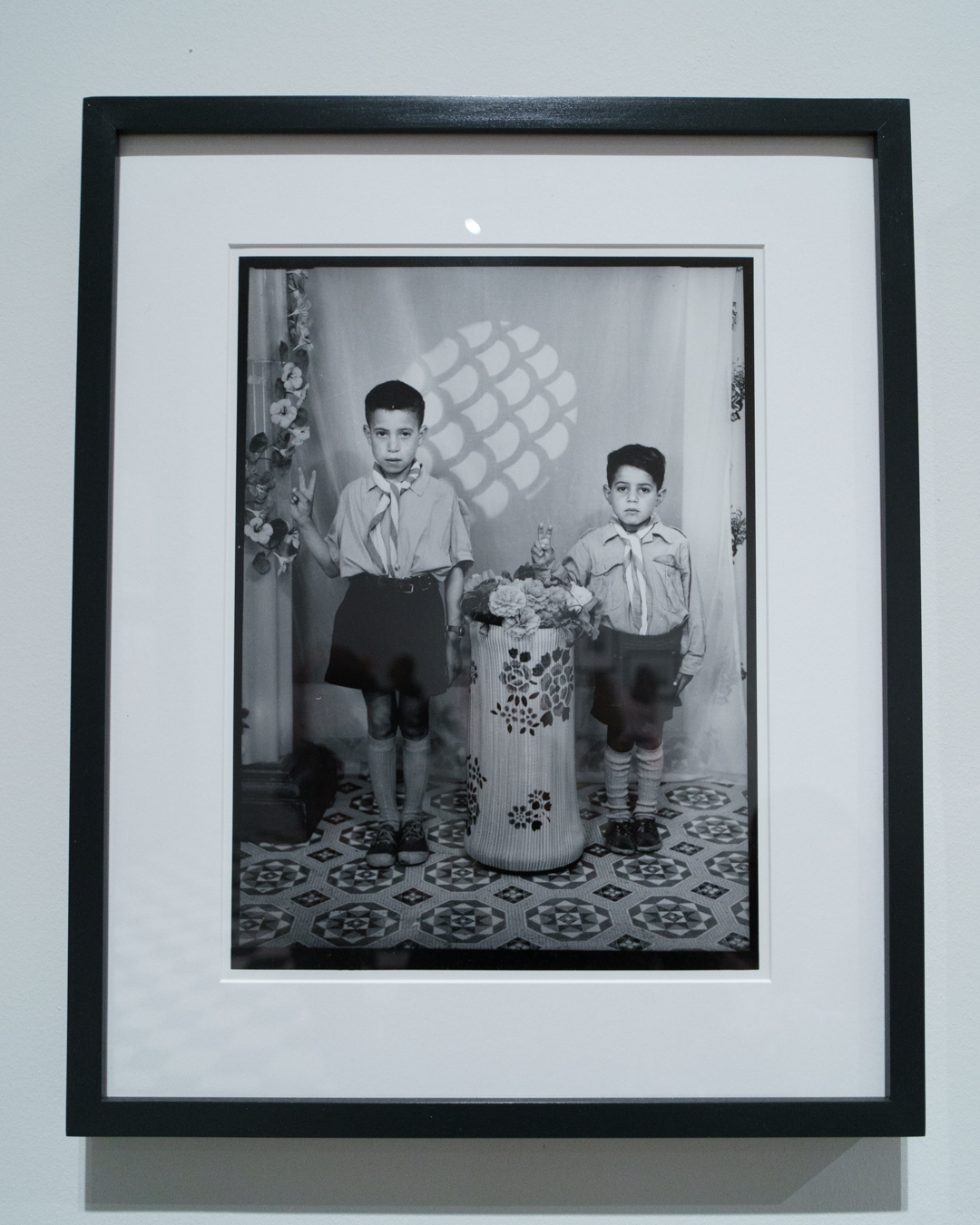

The nuances of photographic styles and techniques play a poignant contextual role in the adoption of Western tropes within the African diaspora. Many images from the first half of the 20th century show the richness of Black families, with some attempting to integrate (including commissioning studio portraits) yet official government photographs of life in Mozambique show only White families with little or no Black individuals (except servants). Meanwhile, photo-montage in the present era allows artists to make critical and personal dialogues with the past.

The exhibition ends with a call to the future, contemplating shared dreams towards a better, unified approach to the climate crisis and our developing ecosystem. Fabrice Monteiro’s The Prophecy series are my favourites works in the show, depicting powerful spiritual figures emerging from rubbish dumps, discarded fishing nets, and burning landscapes, warning us of the environmental issues that face humanity today and in the future, as a result of rapid urbanisation.

This show cleverly weaves its central themes of colonialist critique, lost identities, and challenging public perceptions of the African diaspora across a transhistorical journey that makes their issues feel almost universal. It’s effective and absolutely lives up to its title.

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography runs until 14 January 2024 at Tate Modern, https://www.tate.org.uk/

Leave a comment