I always wanted an exhibition exploring the place of fakes and copies in art history. Suddenly, the Courtauld announced one and I was pumped.

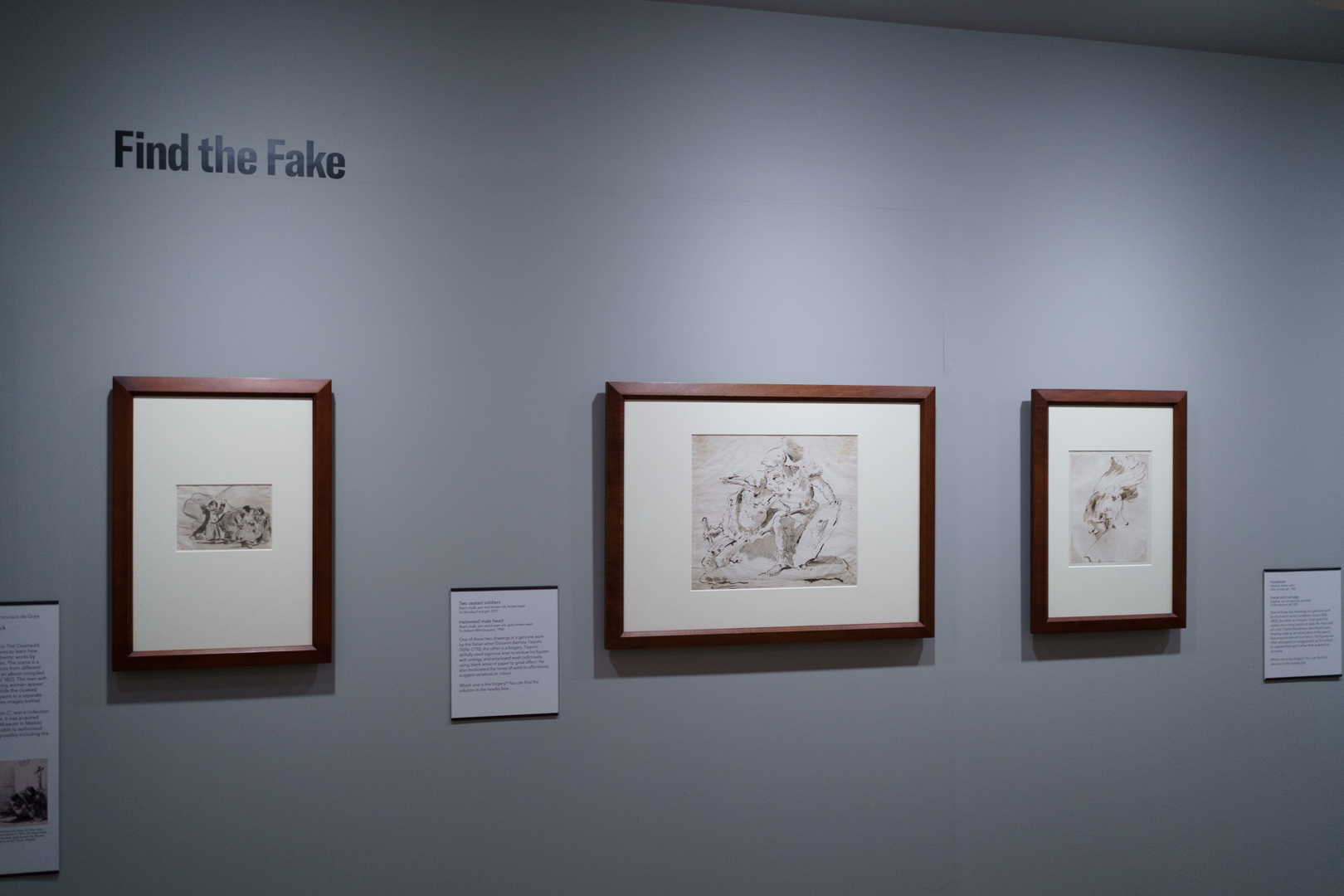

Divided into two parts, Art and Artifice: Fakes from the Collection openly hands us the connoisseurial crown, encouraging us to re-examine problematic works in the Courtauld collection and really look at the visual evidence in front of us. Some were donated specifically as fakes for teaching purposes, others acquired as genuine articles. It’s a detective hunt through and through.

In the paintings department, a forgery by Han van Meegeren greets us at the door. Nearby, a Botticelli aroused suspicion because the Madonna’s face didn’t look quite right. Meanwhile, there are also terrible versions of Seurat and Bruegel paintings. It’s all quite hilarious.

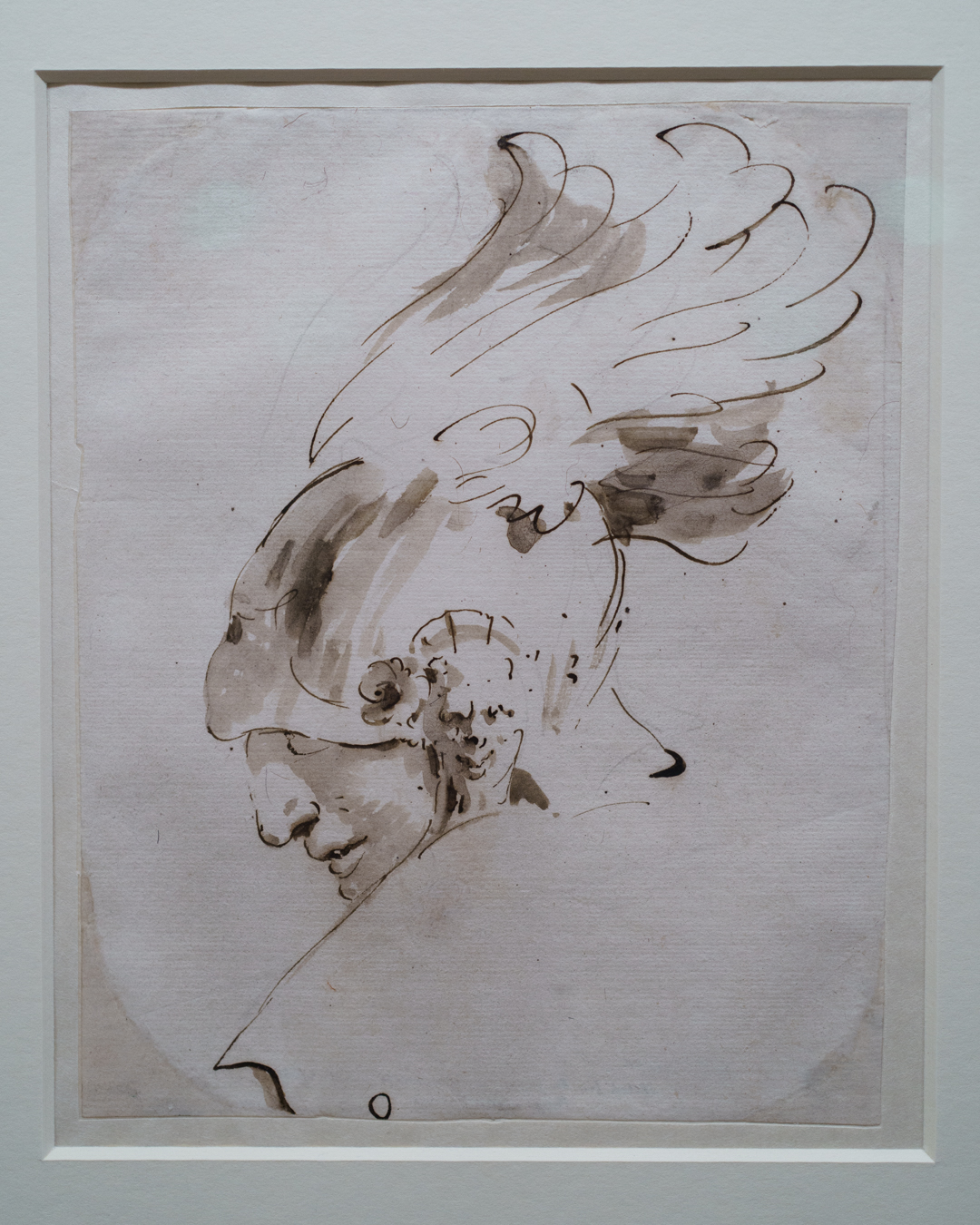

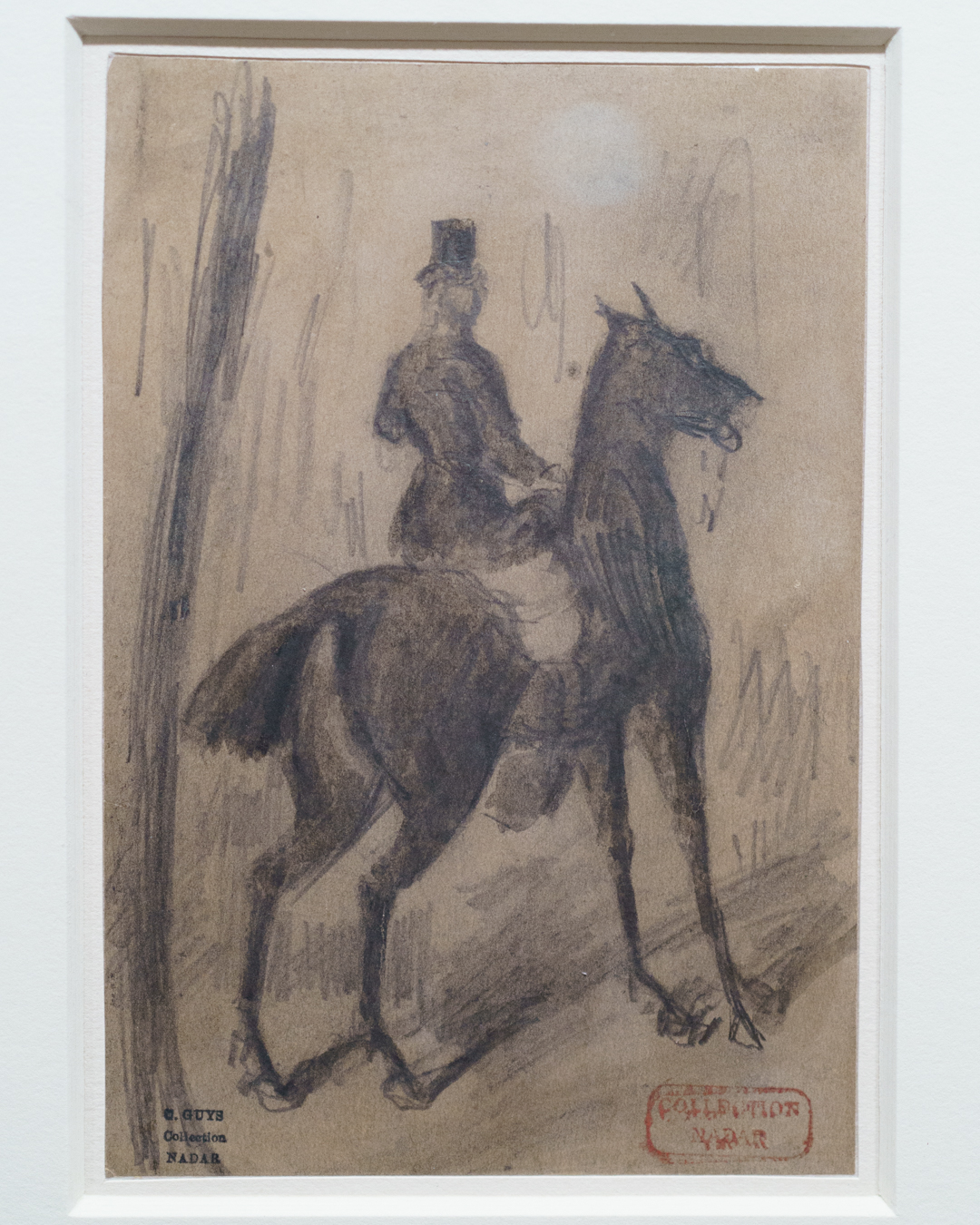

But the drawings are the testy ones. One wall of Tiepolo and Constantin Guys drawings invites us to spot the fake, while another asks for your opinion on a contested Michelangelo drawing. Your eyes will be tested and your mind possibly blown.

Armed with a wealth of information, modern forgers like Eric Hebborn made his own inks and sourced period-specific paper, preferably without identifying watermarks. A few were sold and identified in the Courtauld; others were claimed and disproved to be his doing.

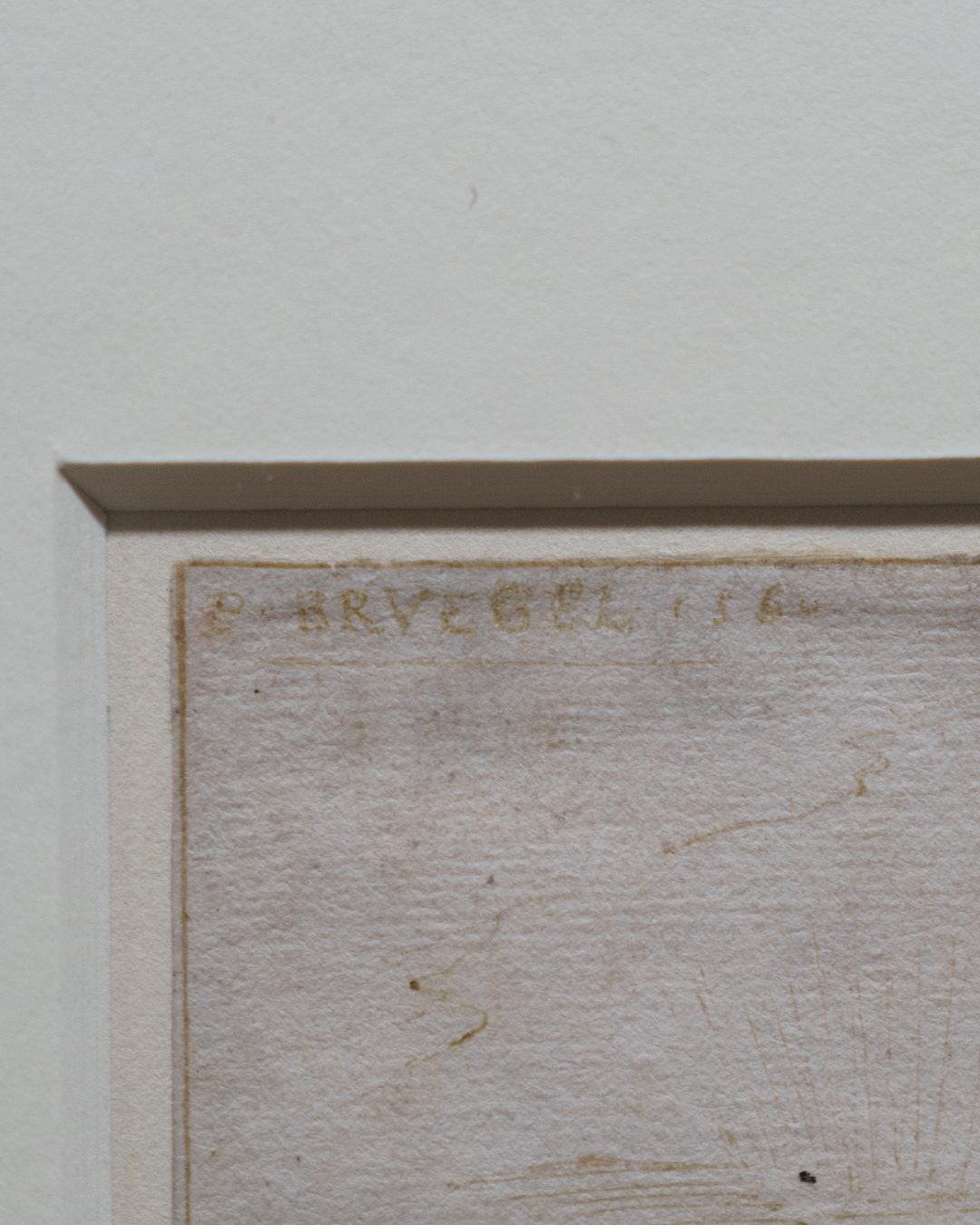

But the early modern period wasn’t so clever. A fake Bruegel signature features on a nice Jacob Savery landscape drawing, but the watermark post-dates Bruegel’s life. Similarly, two Louis-Philippe Boitard drawings on a single mount bear near-identical depictions of a child’s head; one is on laid paper, the other on wove paper, invented in 1857, only a year before Boitard’s death and not widely available until 20 years later.

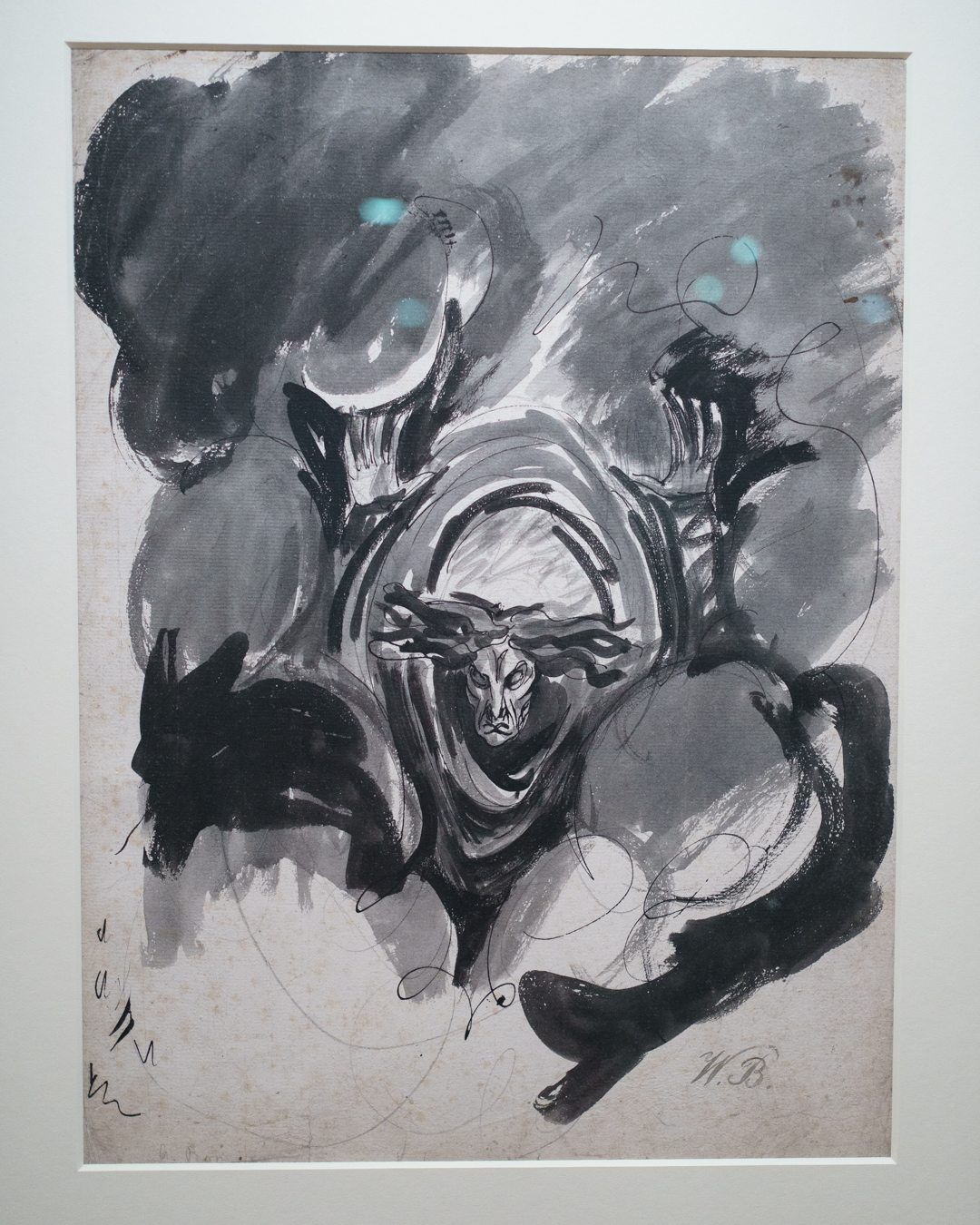

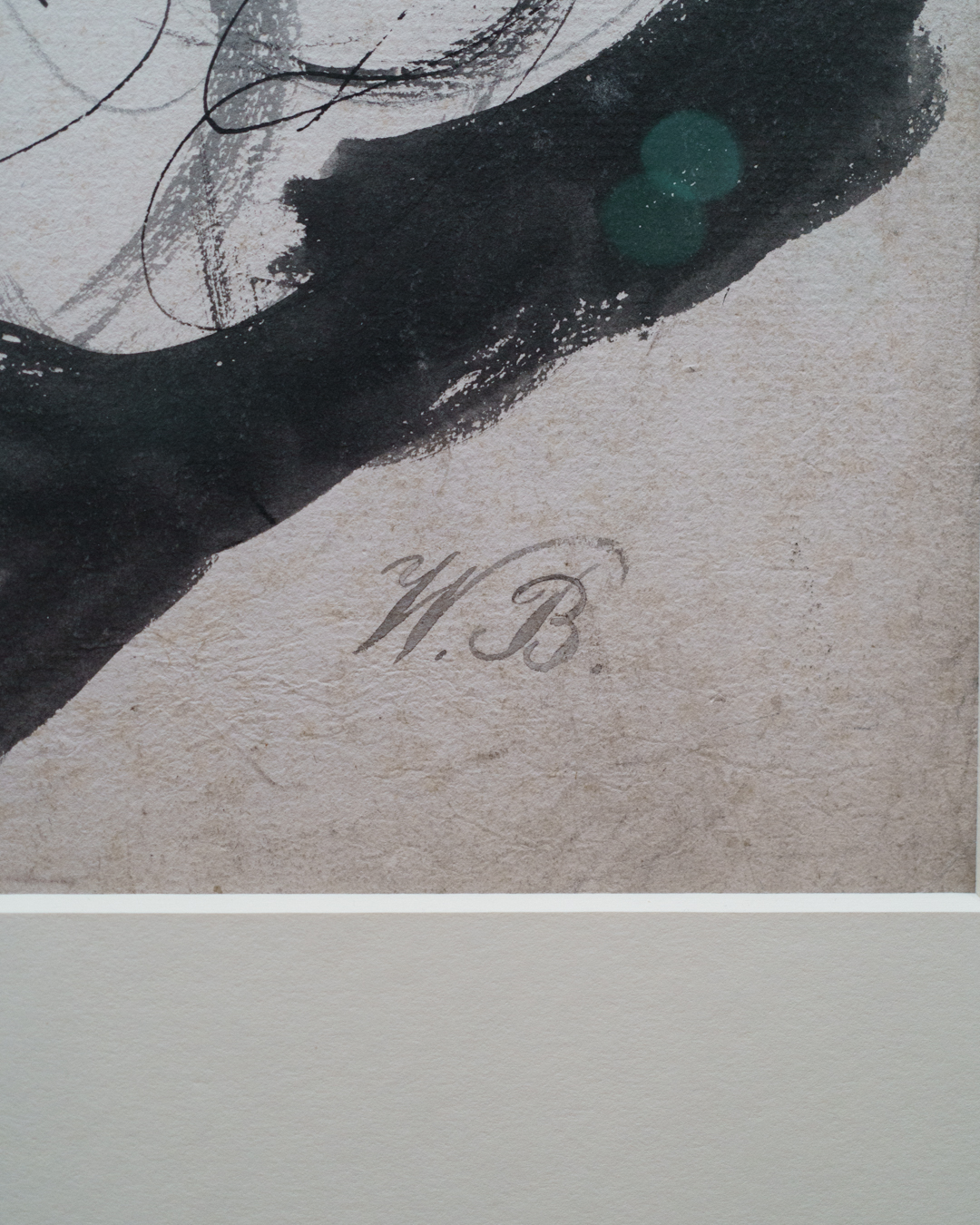

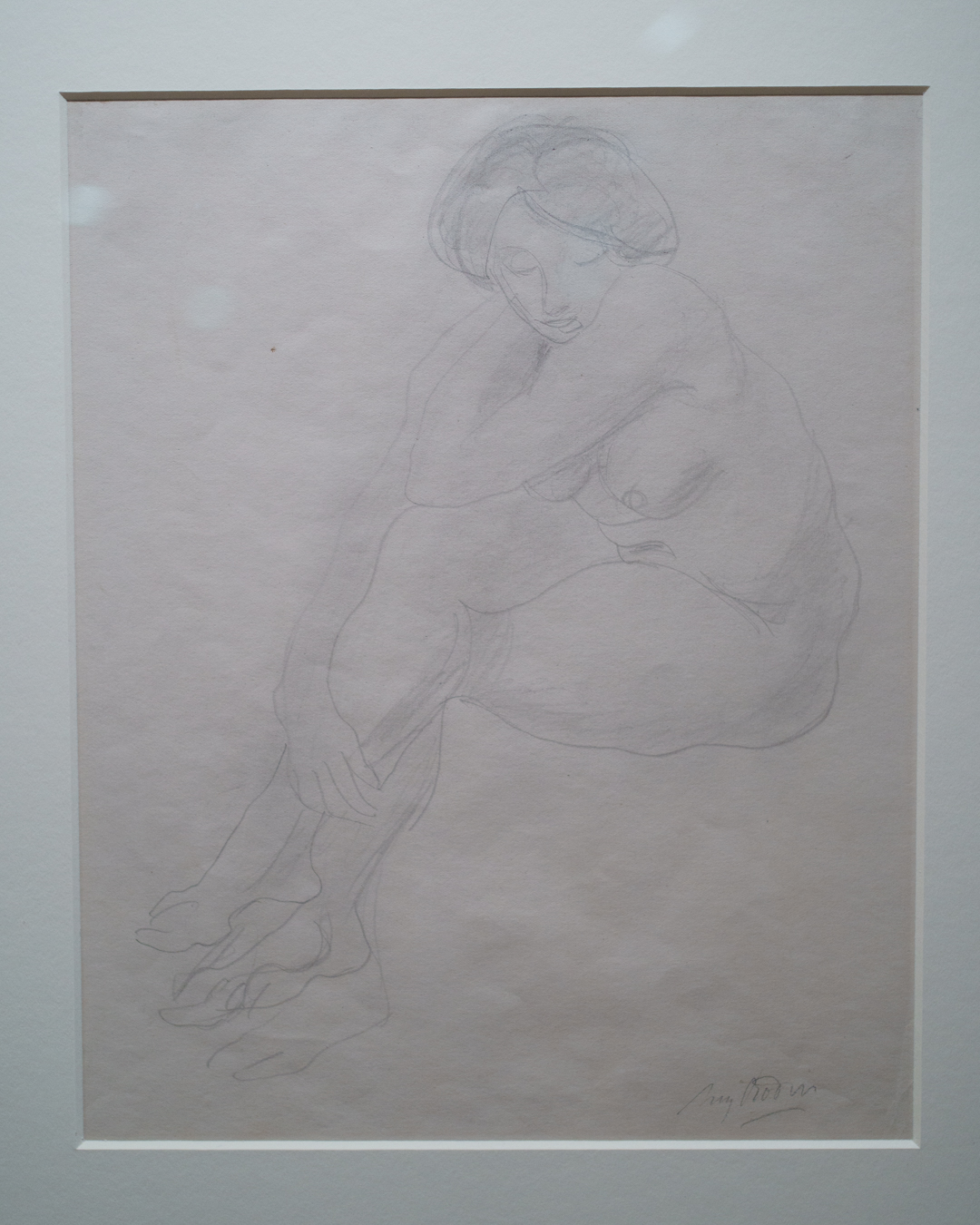

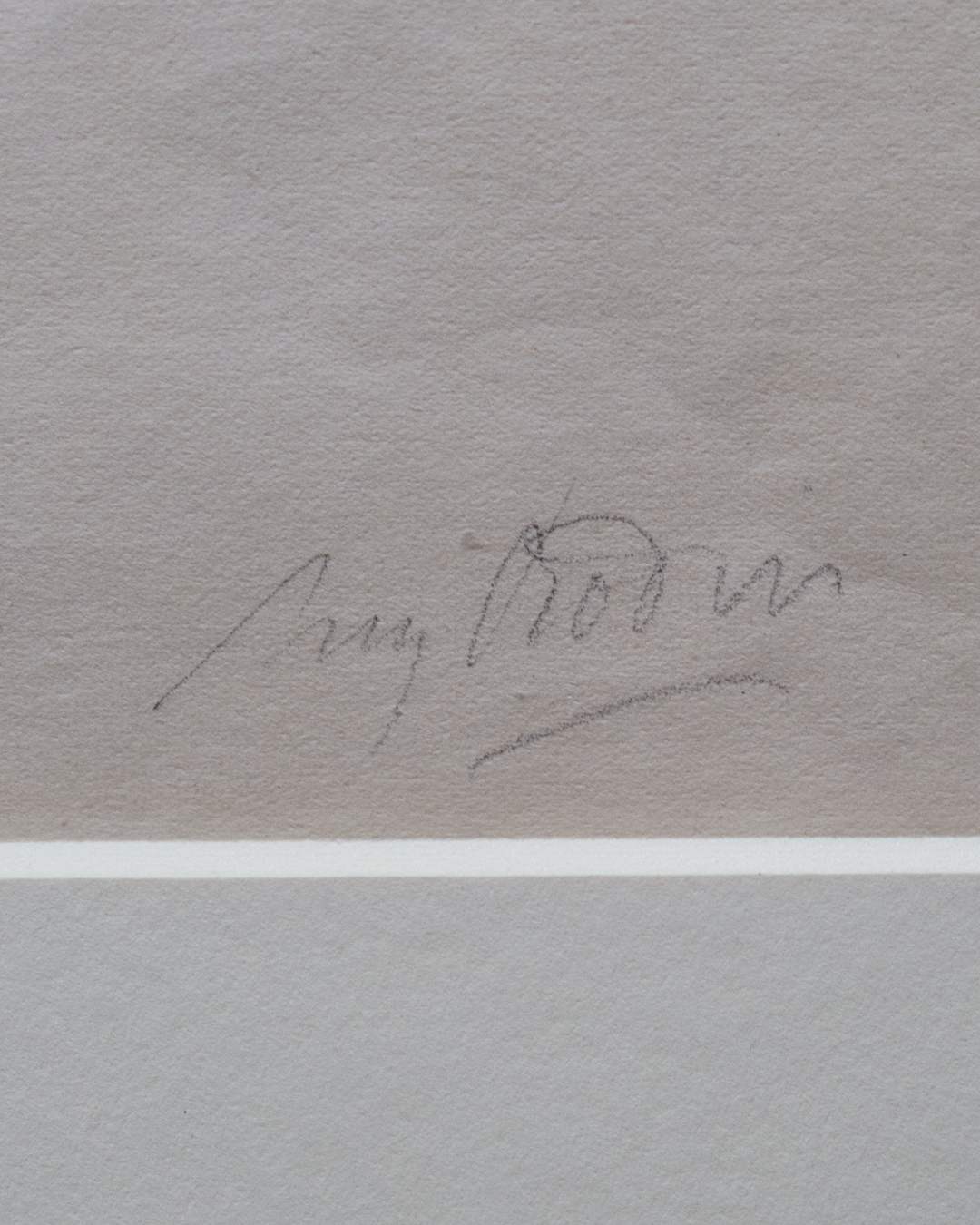

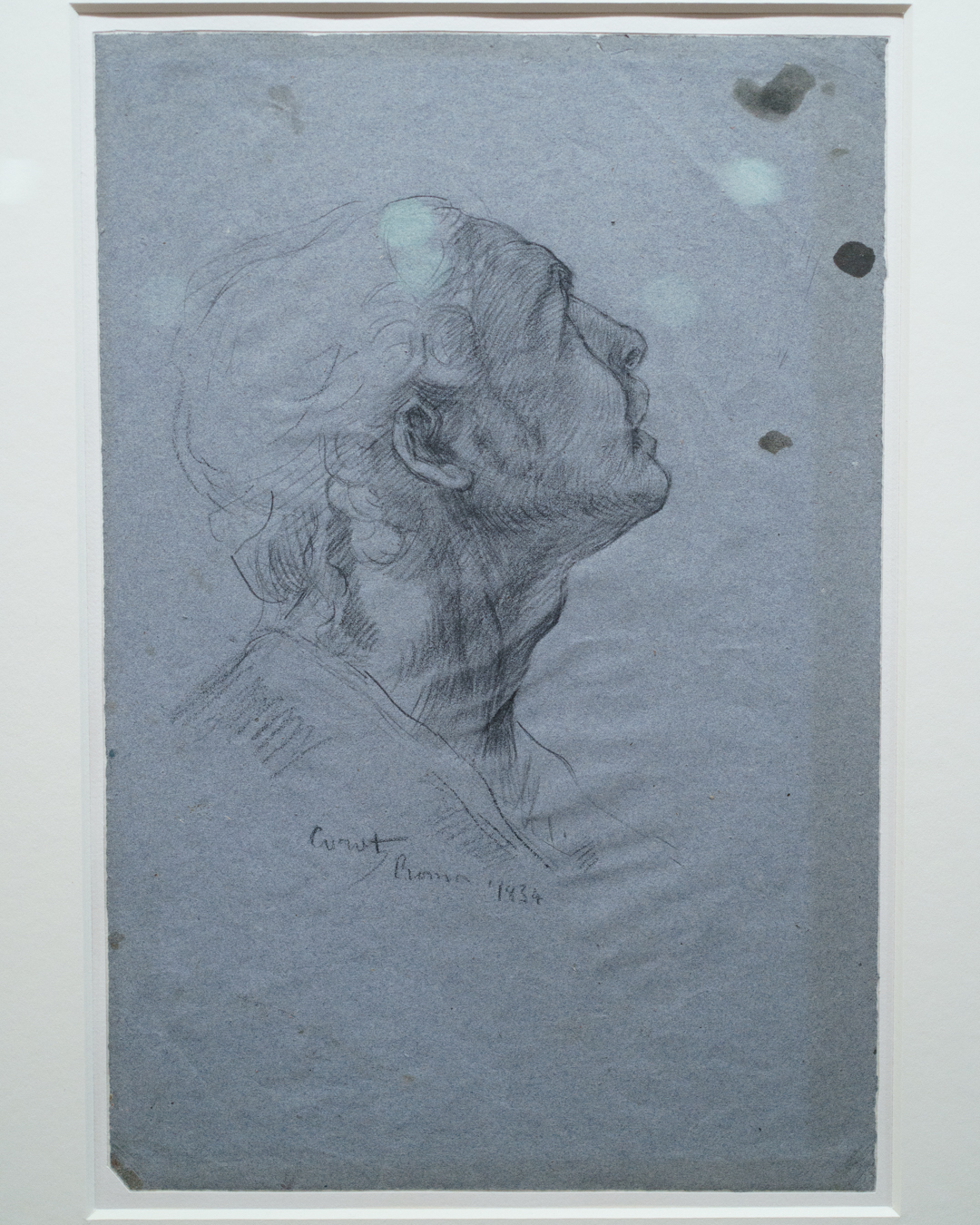

Other deceptive features are common enough and we learn never to trust them anyway. A fake William Blake monogram on a genuine George Romney to increase its commercial value; a Rodin drawing that looks slightly nicer than a real Rodin (they’re usually more free-flowing and loose). Someone even went far enough to fake an esteemed Pierre-Jean Mariette mount and his collector’s mark to add prestige to the provenance of a Jacopo Ligozzi drawing. Or perhaps a signed and dated Corot drawing claiming he visited Rome in 1834; the handwriting is wrong and Corot actually did Rome in the late 1820s.

One especially sneaky forger capitalised on Rubens’ well-known practice of retouching drawings he collected, to ‘correct’ them. It’s an edge case in a centuries-long history of deception and deceit. An engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi copying a Dürer woodcut is a famous recorded example in the early modern period’s culture of copying (more about this HERE). The ability to copy well was a highly regarded skill expected of great artists in training; a teenage Michelangelo famously forged an antique head of a faun to secure the patronage of Lorenzo il Magnifico.

Even if a modern fake is technically accomplished, can we really dismiss them outright, or can we view them as independent works of art in the same way we look at earlier copyists? Personally, I think forgers have an attributional toolkit that even art historians envy. They might even make great conservators.

This exhibition bravely sheds away the mystique of attribution methodologies and engages us in discussion about the changing definition of fakes and copies, and their place in art history and the commercial art world. It’s a fascinating display that deserves its own digital resource and opportunities for feedback.

Art and Artifice: Fakes from the Collection runs until 8 October in the Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Drawings Gallery and Project Space of the Courtauld Gallery, London, https://courtauld.ac.uk/

Leave a comment