Recently, I finally had the chance to view George Frederic Watts’ huge fresco in the Great Hall of Lincoln’s Inn, open just once a year as part of the Open House Festival. The estate is home to the Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn which provides training for future barristers and maintains its existing community of legal professionals.

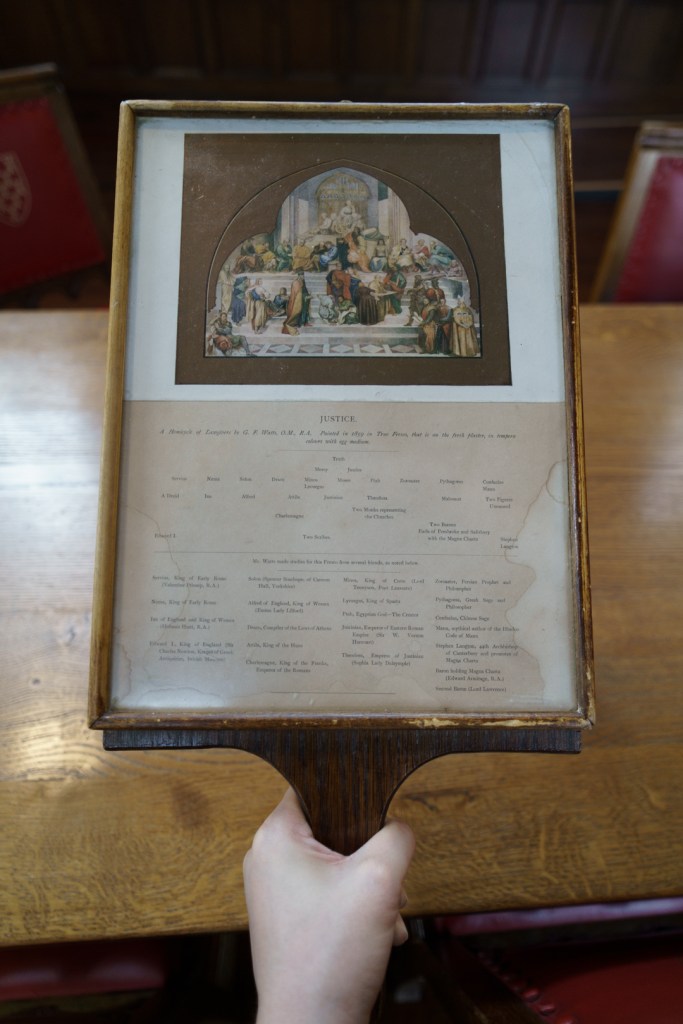

Situated on the north wall, Justice: A Hemicycle of Lawgivers (completed October 1859) served as a perspectival extension to the Tudor-inspired hall (built 1843-45), and also as a conduit to the past. The hall evokes the one in Hampton Court Palace and still functions as the Society’s dining area.

The participatory nature of this fresco meant that the gathering of past rulers (Edward I, Alfred the Great, Attila the Hun), philosophers (Confucius, Zoroaster, Pythagoras), even the Egyptian god Ptah, was ‘completed’ by the present lawgivers (Benchers of the High Table) sat on the raised platform beneath it, and the future lawgivers (barristers and students). In other words, the fresco acts no different than a Last Supper scene in the refectory of most Italian churches.

Some of the figures were modelled from close friends such as; Alfred Tennyson as King Minos; William Holman Hunt as Ina of England; Sophia Lady Dalrymple as Theodora, Empress of Justinian, etc. The sculptures represent Justice, Truth, and Mercy.

In June 1842, Watts approached the Society with an offer to paint a fresco for them, for free, asking only for the cost of materials. This was part of Watts belief in ‘awakening a national sense of art’, advocating for large-scale wall paintings in fresco to decorate public buildings.

‘I venture to make to the Benchers and students of Lincoln’s Inn the following proposition, namely, if they will subscribe to defray the expenses of the material, I will give designs and labour, and undertake to paint in fresco any part or the whole of the Hall’

G.F. Watts, June 1842

Work began on 19 April 1854, taking a long 5 years to finish; fresco painting requires working quickly, with each section completed before the freshly-laid wet plaster dries up completely. By contrast, the whole of the Sistine Chapel ceiling took Michelangelo just 4 years.

This was because Watts was frequently ‘so very ill that it has been out of my power to do any work at all’, preferring to travel abroad as a consequence of his ill health. Scaffolding stayed in place for years, and an 1856 Council meeting prompted a removal.

‘I have been long suffering from an affection of the brain of a very severe kind and am promised recovery only upon condition of abstaining from all work and spending the winter in a warm climate.’

G.F. Watts to Philip C Hardwick, August 1856

On 14 June 1857, Watts wrote to say that he was back in England and anxious to start work on the fresco again. Another bout of ill health delayed some already significant progress, but eventually ‘a month’s good work would suffice to bring it to a close…[in] the long days of next vacation’ and it was finished at last, praised by friends and critics.

Yet, Watts himself had mixed feelings, veering between the conclusion that this had been a wasted opportunity – ‘I don’t mean to say it is a disgraceful or mean failure, but it is a failure’ – to claiming the work as ‘perhaps the best thing I have done or am likely to do’. He was also proud to point out the work’s status as ‘the only true fresco’ in the country; this does appear to be the case.

Pleased with Watts’ fresco, the Society gifted him 500 sovereigns ‘in a handsome purse contained in a silver cup’ as thanks (‘a complimentary, a friendly, and a grateful remembrance.’), rather than as remuneration or compensation. After his death, Watts’ widow, Mary Setton Watts, gifted the silver-gilt ciborium back to the Inn in 1925.

In her biography of her late husband, Mary recalls his working methods when tackling the Lincoln’s Inn fresco:

‘preferring to work without having made any cartoon…made drawings, sometimes on so small a scale that the whole composition went into half a sheet of notepaper; no study seems to have been larger than a medium-sized sheet of drawing-paper could carry, though many of the heads of the legislators were drawn or painted life-size, his friends being laid under contribution in some degree as models for the various types’

Mary Watts, George Frederic Watts – The Annals of an Artist’s Life, London, 1912, Vol I, p.150-51

Upon his death in 1904, many of the related drawings for Justice: A Hemicycle of Lawgivers were bequethed to the Royal Academy of Arts.

You can read more about the project on the Society’s website.

Leave a comment