I really like The Rossettis at Tate Britain, but not for the reasons it set me up to expect. Veiled under a survey of the Rossetti family is in fact a Dante Gabriel retrospective in which there were no other voices but his own. Everything was either through the eyes of Gabriel or in dialogue with him, shifting focus to his models/lovers instead of his actual family.

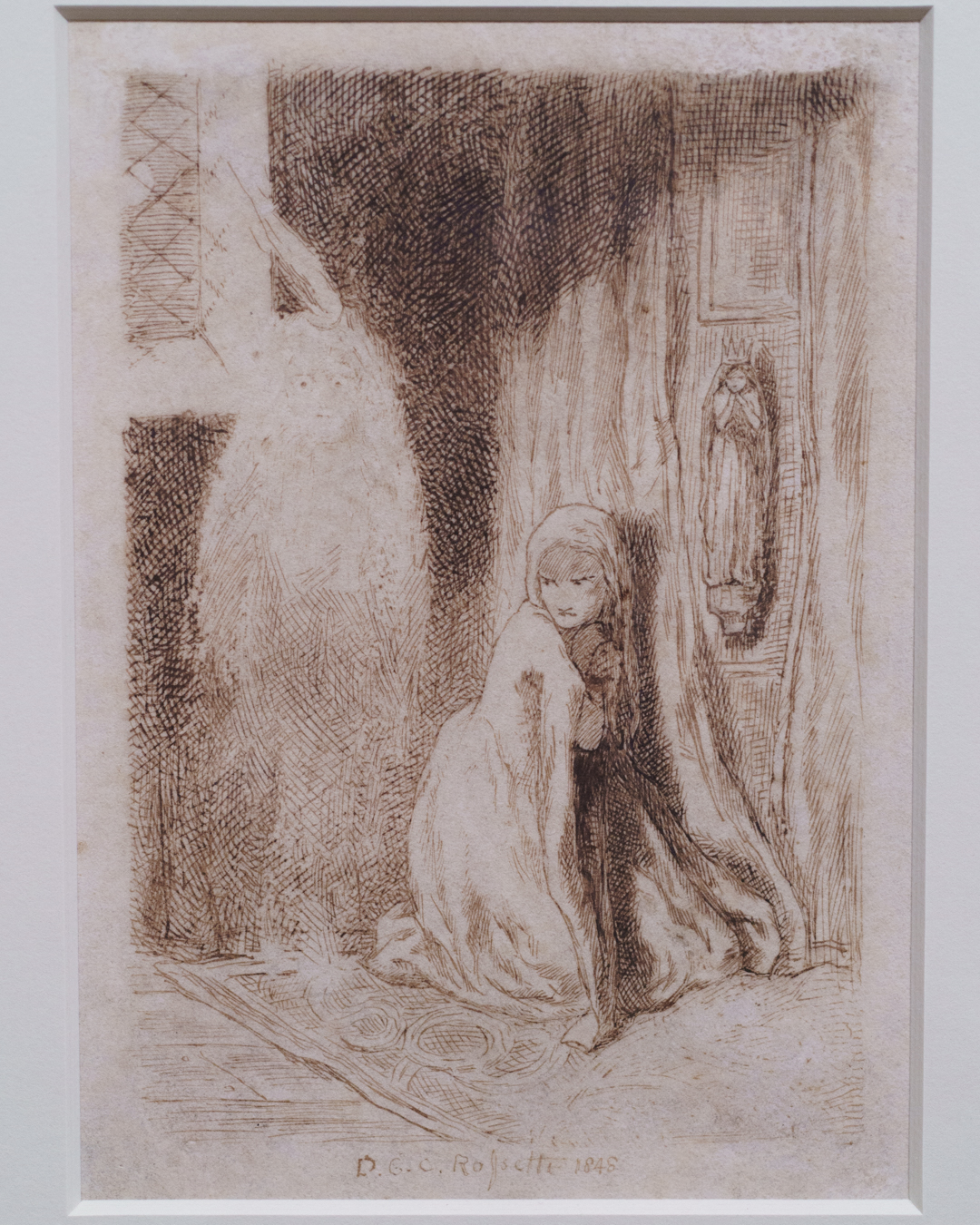

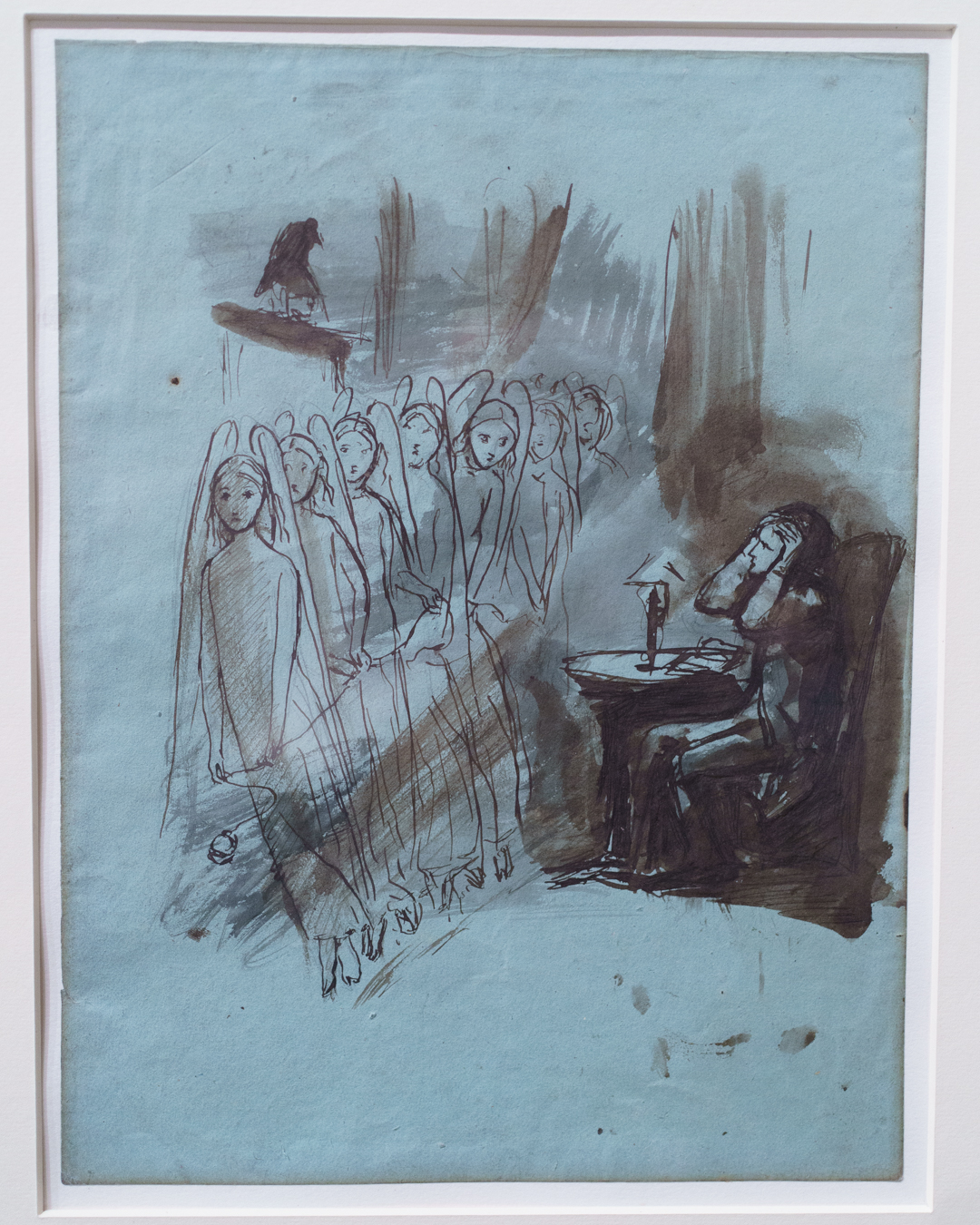

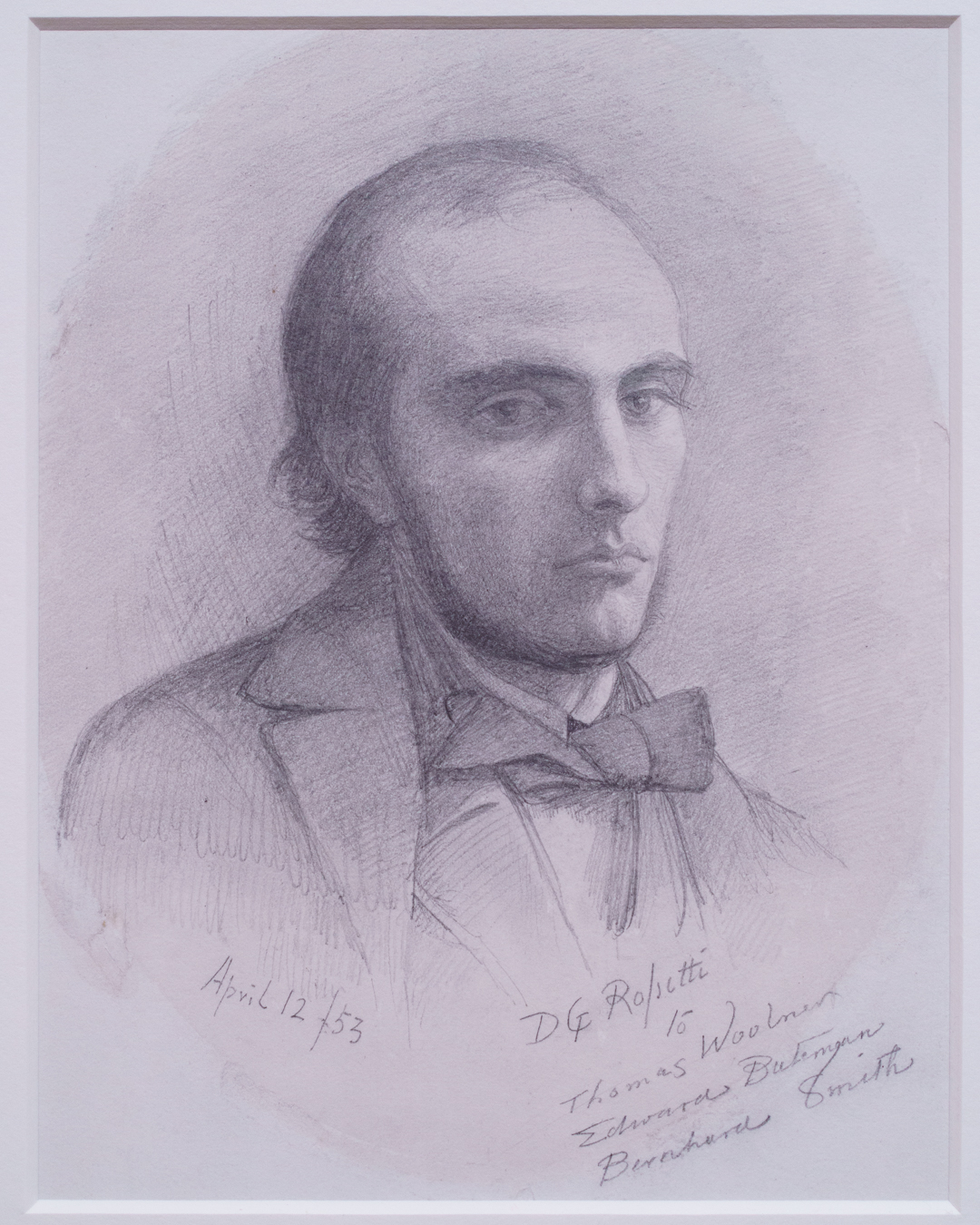

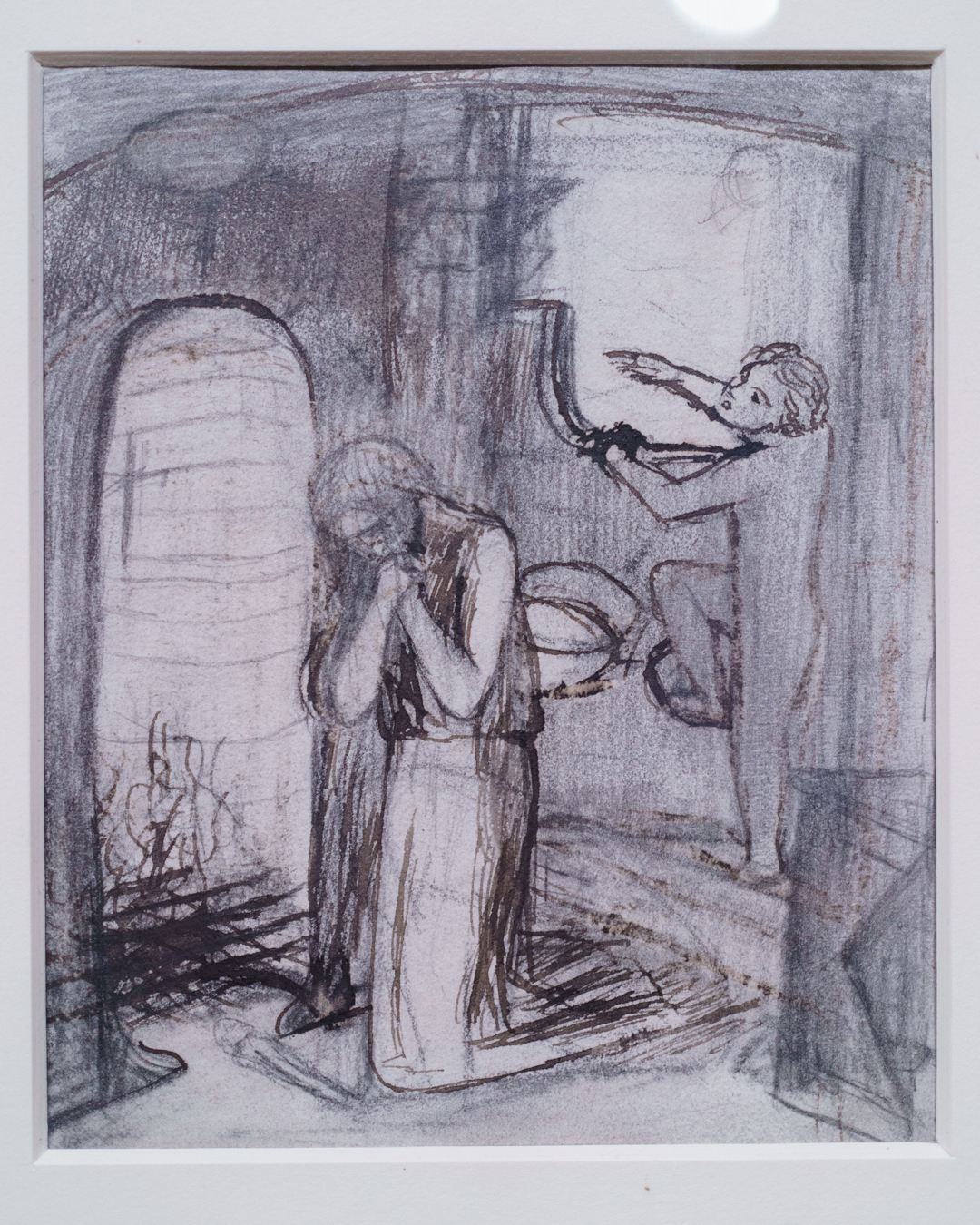

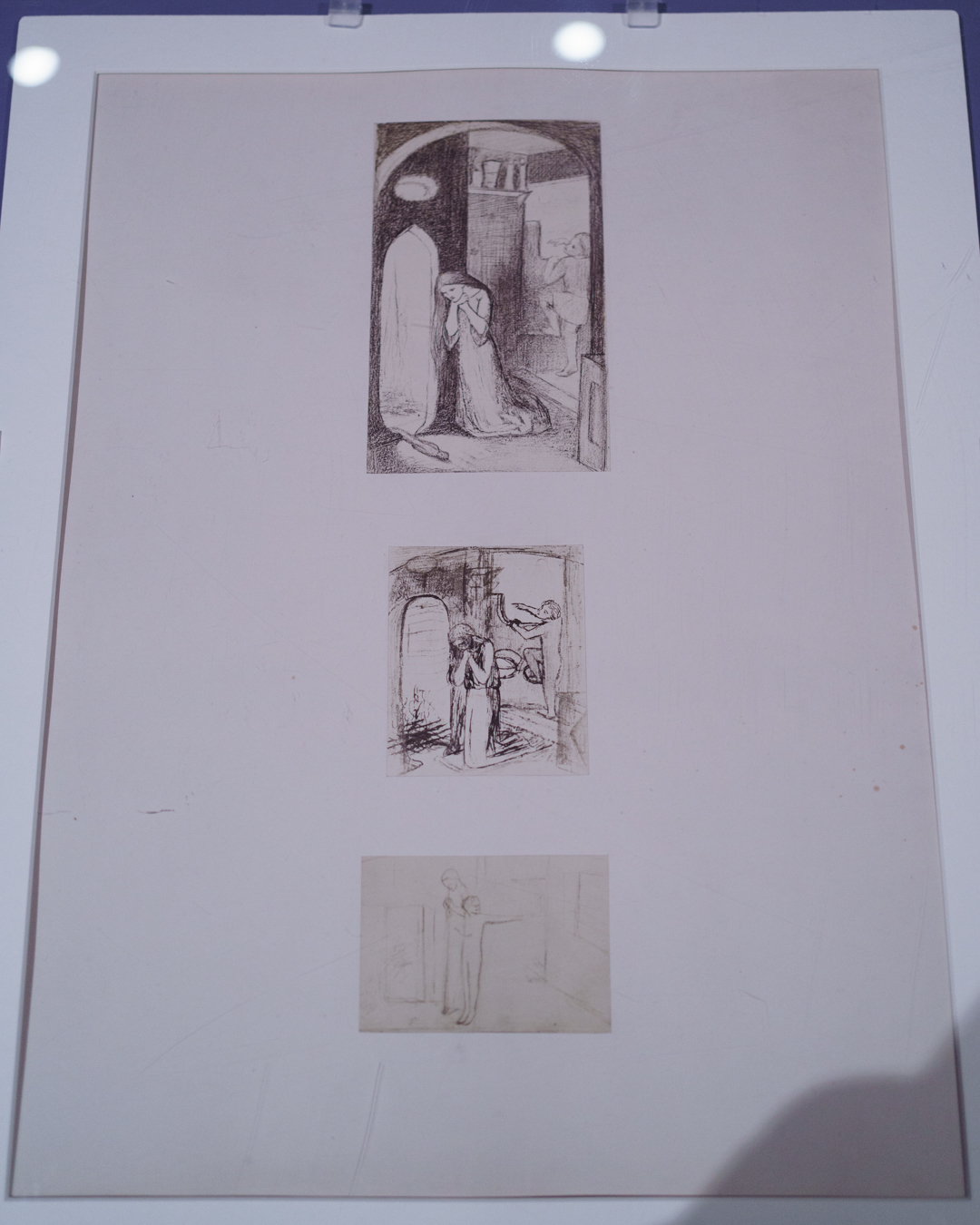

There is a very interesting section on his early drawings preceding the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s formation in 1848, some showing the graphic influence of Paul Gavarni and George Cruikshank, and others incorporating cut-and-paste methods (which are not mentioned!). I also admired the brilliant gathering of works relating to Found (Delaware Art Museum) probably the largest of its kind.

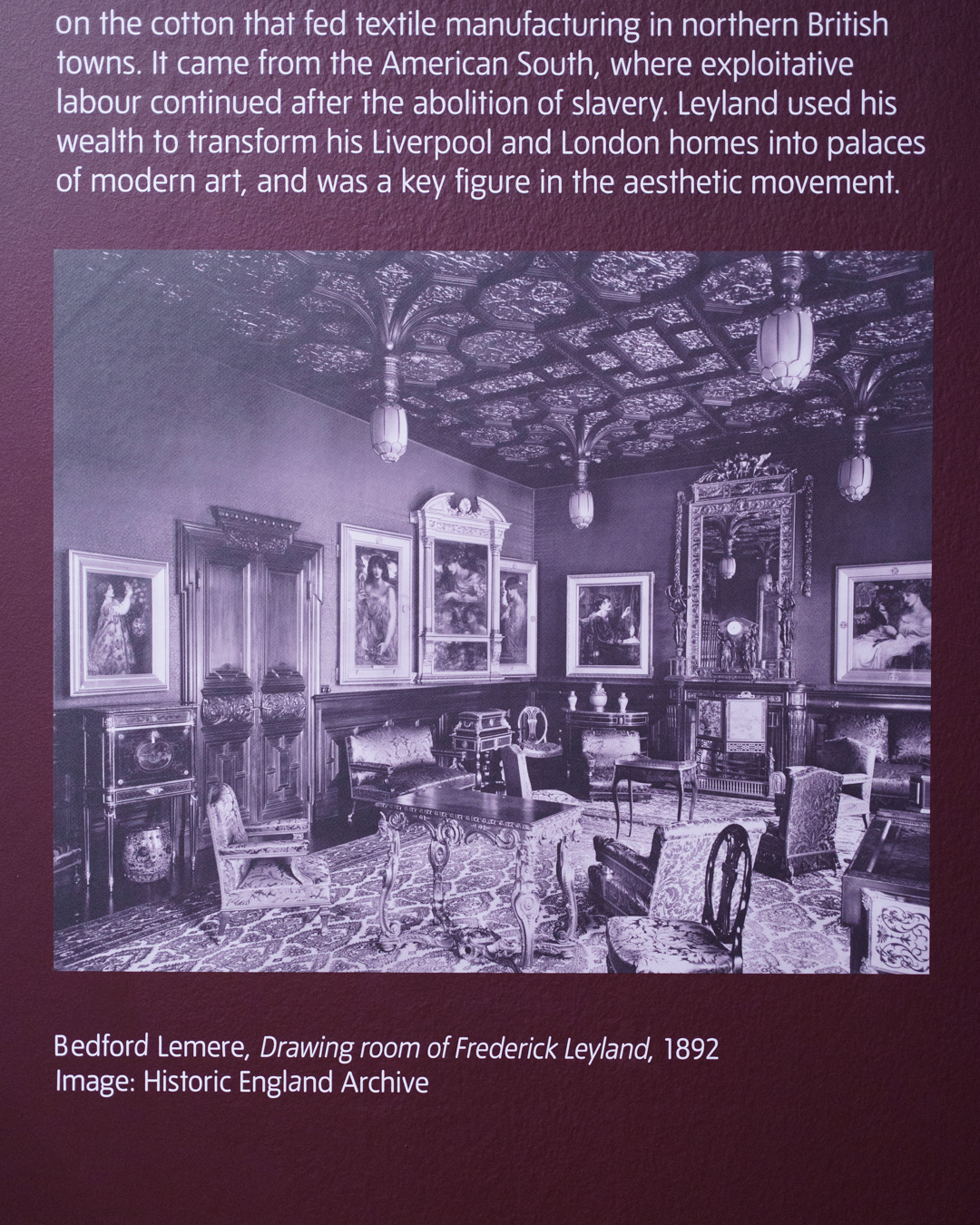

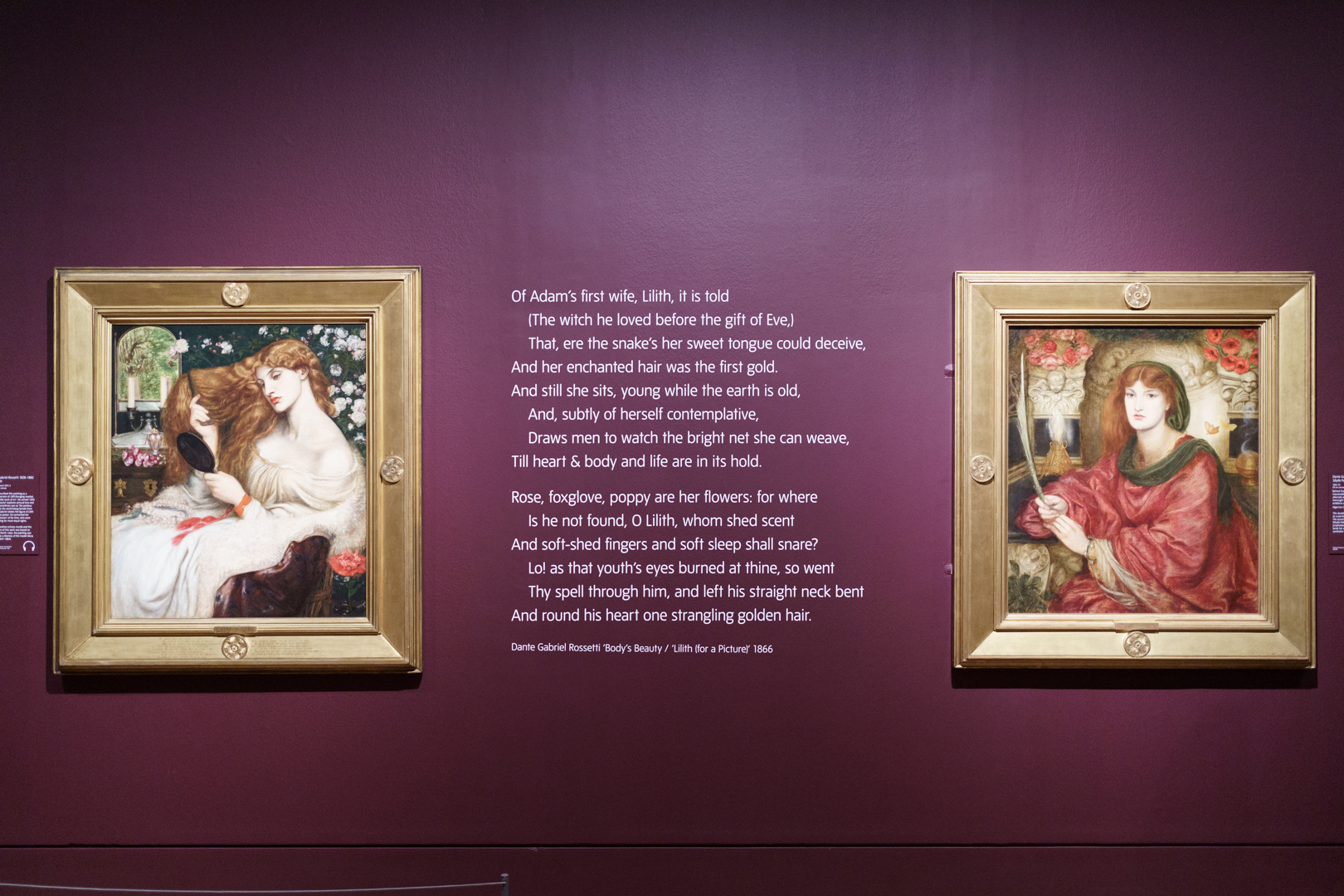

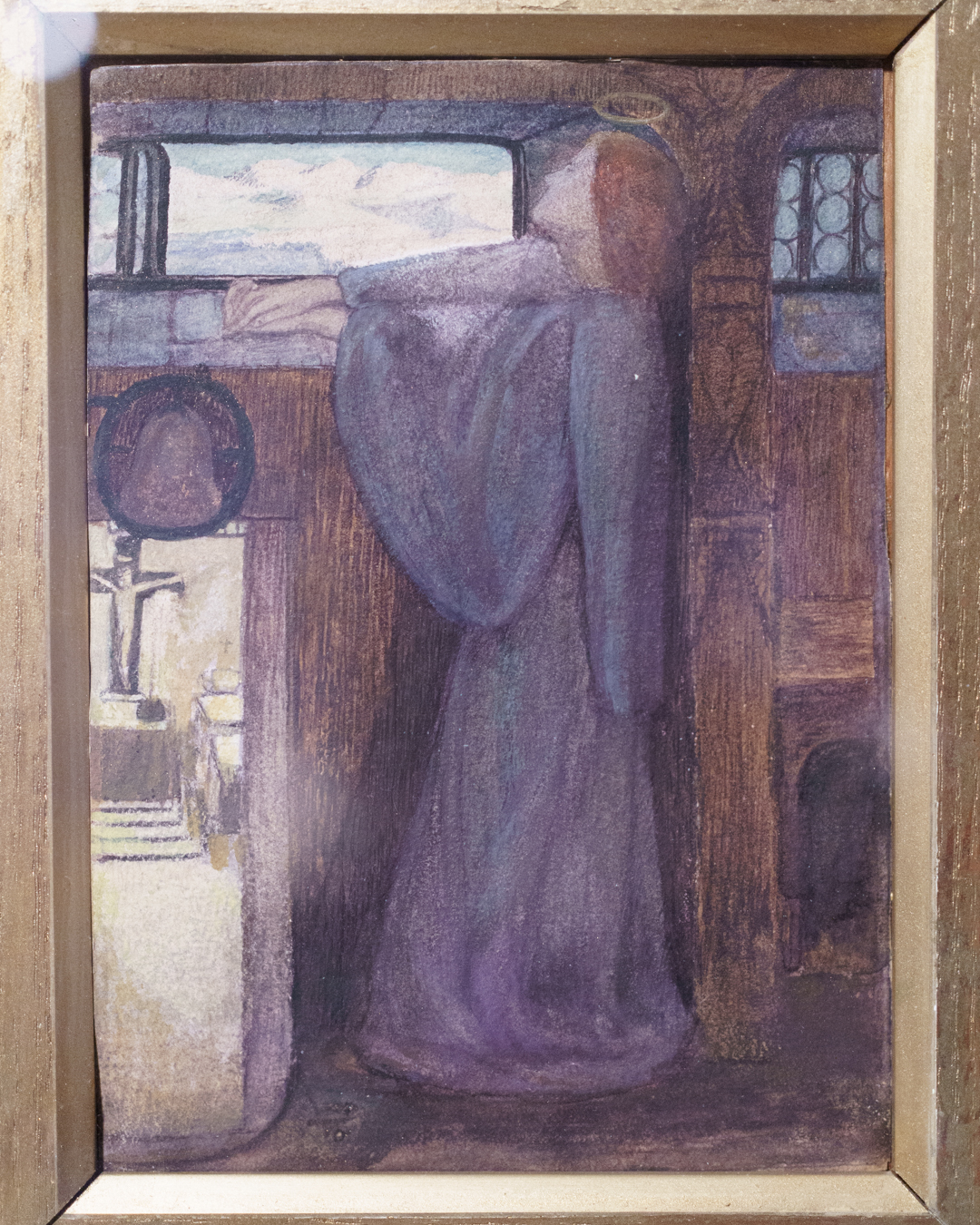

Finally, one is treated to an exceptional hang replicating Frederick Leyland’s drawing room, featuring Gabriel’s revival of the Renaissance predella panel in The Blessed Damozel (Lady Lever Gallery, Port Sunlight), itself a replica of the original commission from William Graham. Yet, with all the mention of ‘double works of art’ (interplays of text and image in a single piece), nothing is mentioned about how the inscribed poetry on the frames themselves enforced this radical hallmark of Gabriel’s art-making, as in the case for Lady Lilith (Delaware Art Museum).

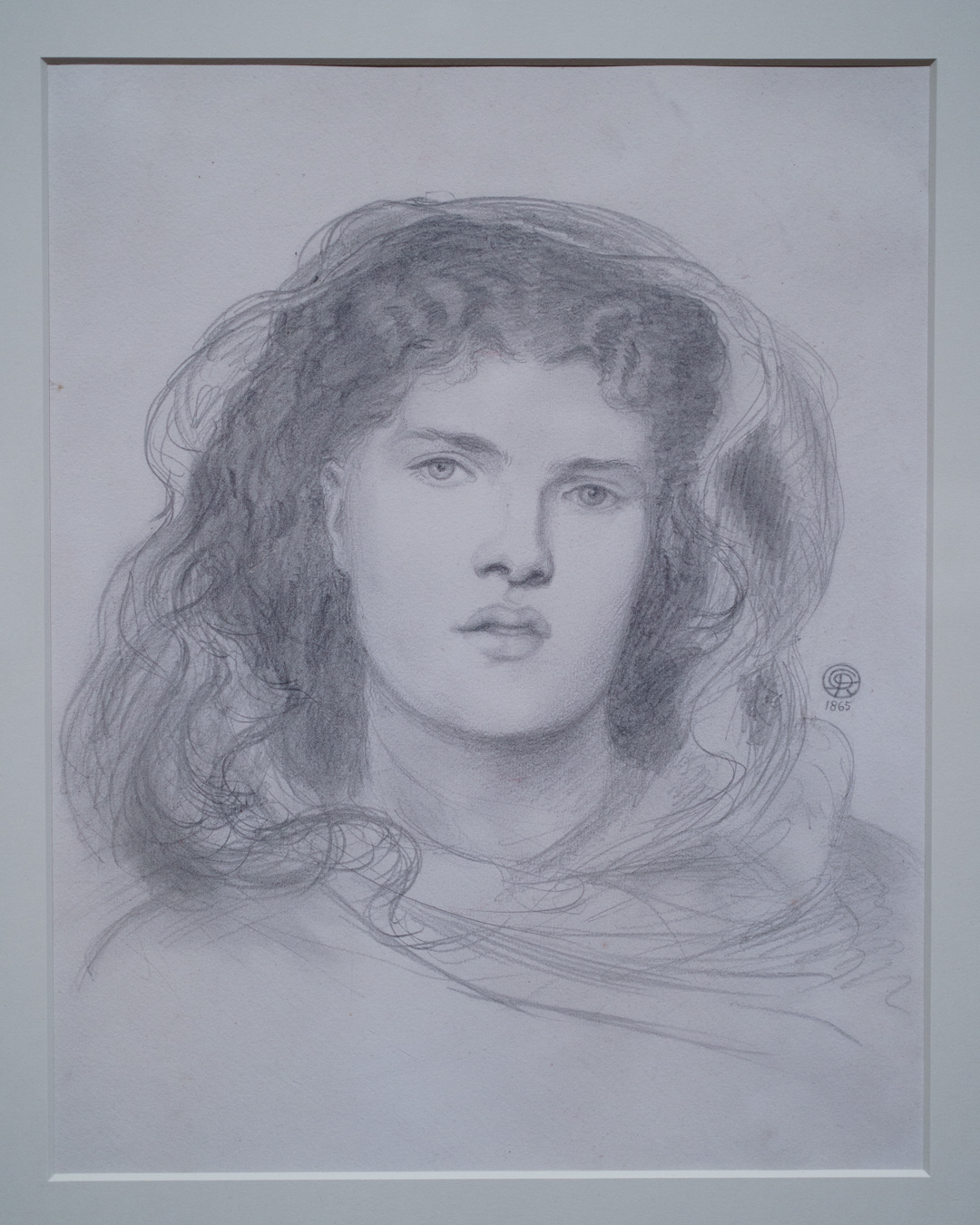

A final treat is the impeccable vista of Jane Morris guises, juxtaposed against 13 rarely-seen photographs by John Robert Parsons of her posing in Gabriel’s garden at 16 Cheyne Walk.

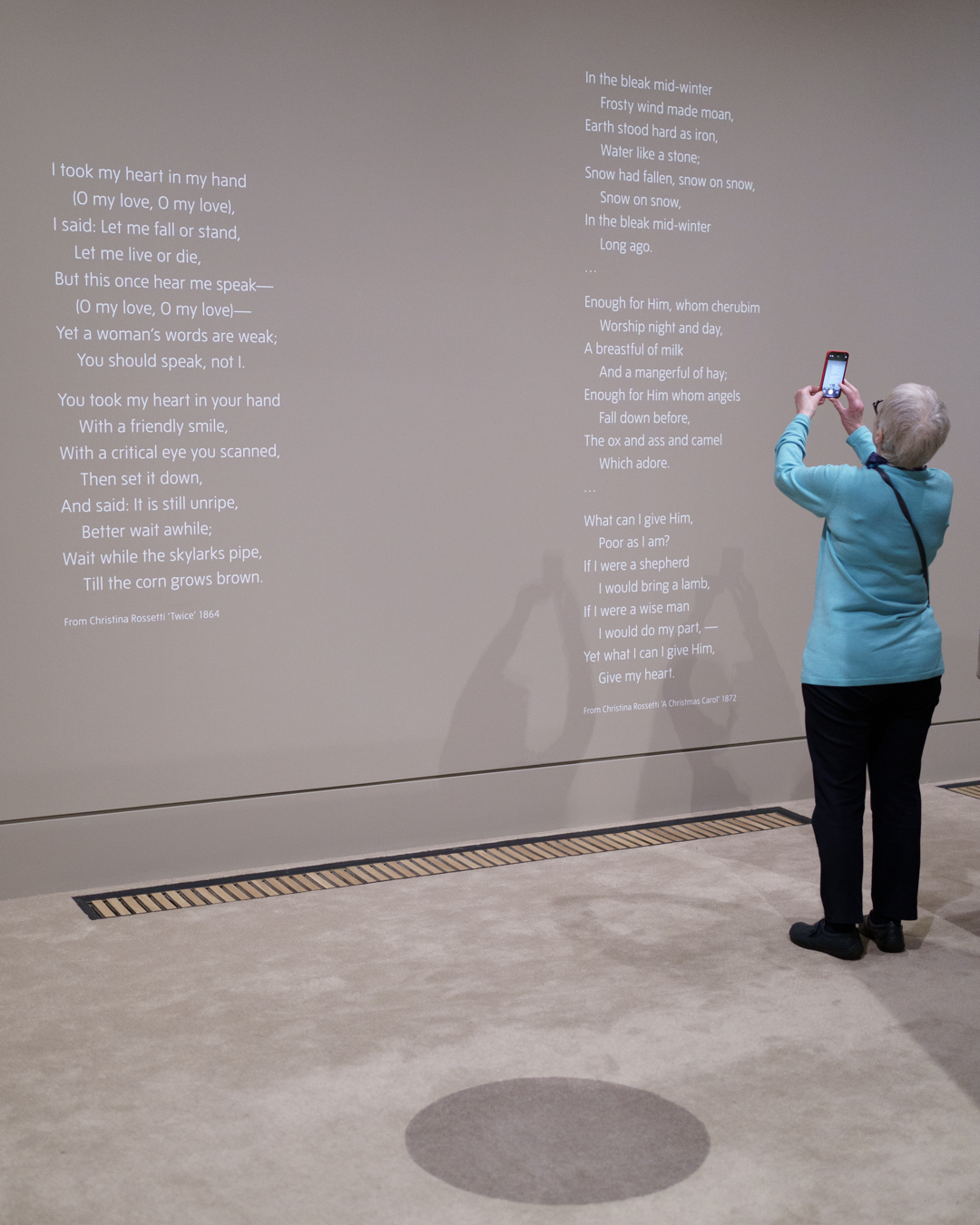

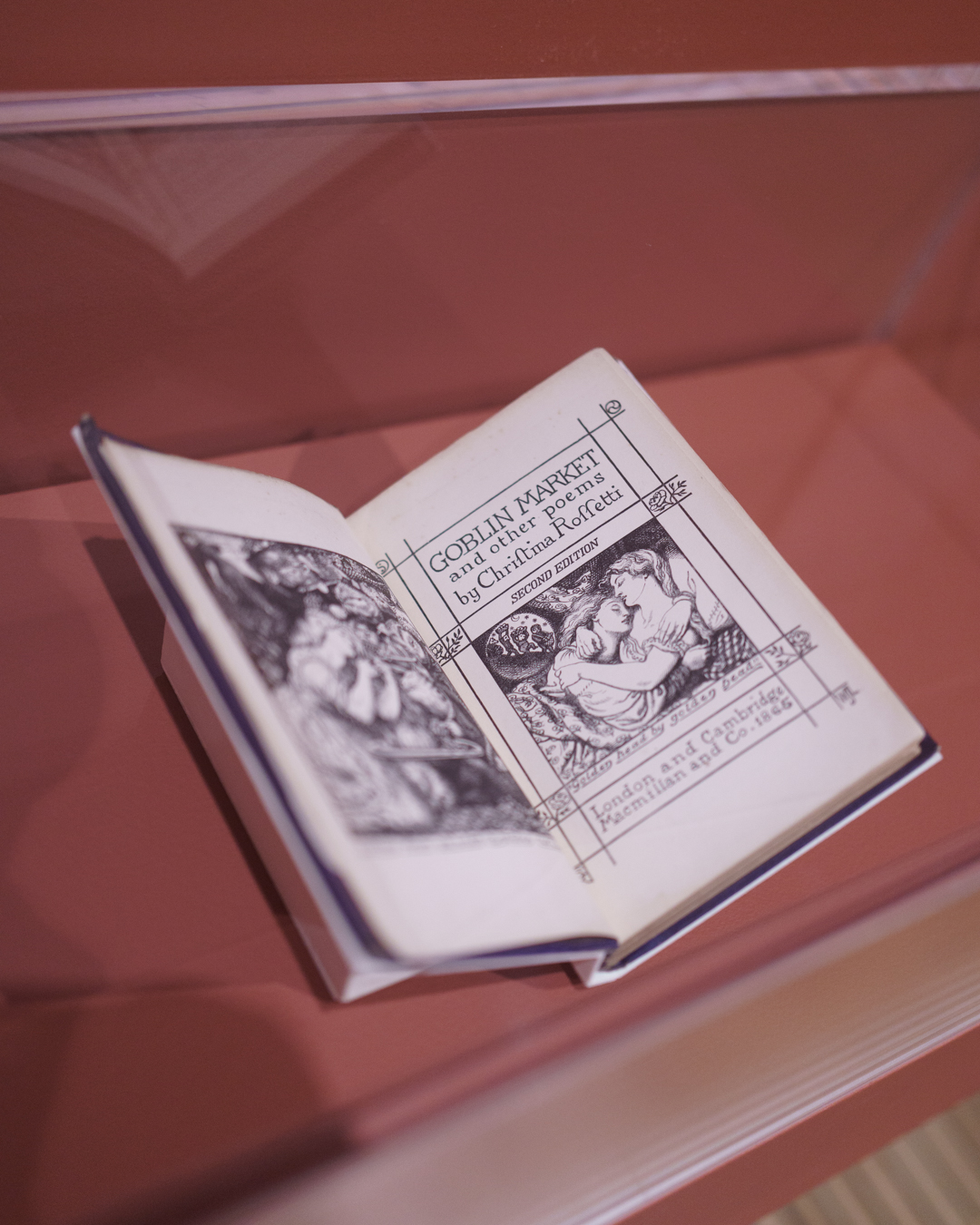

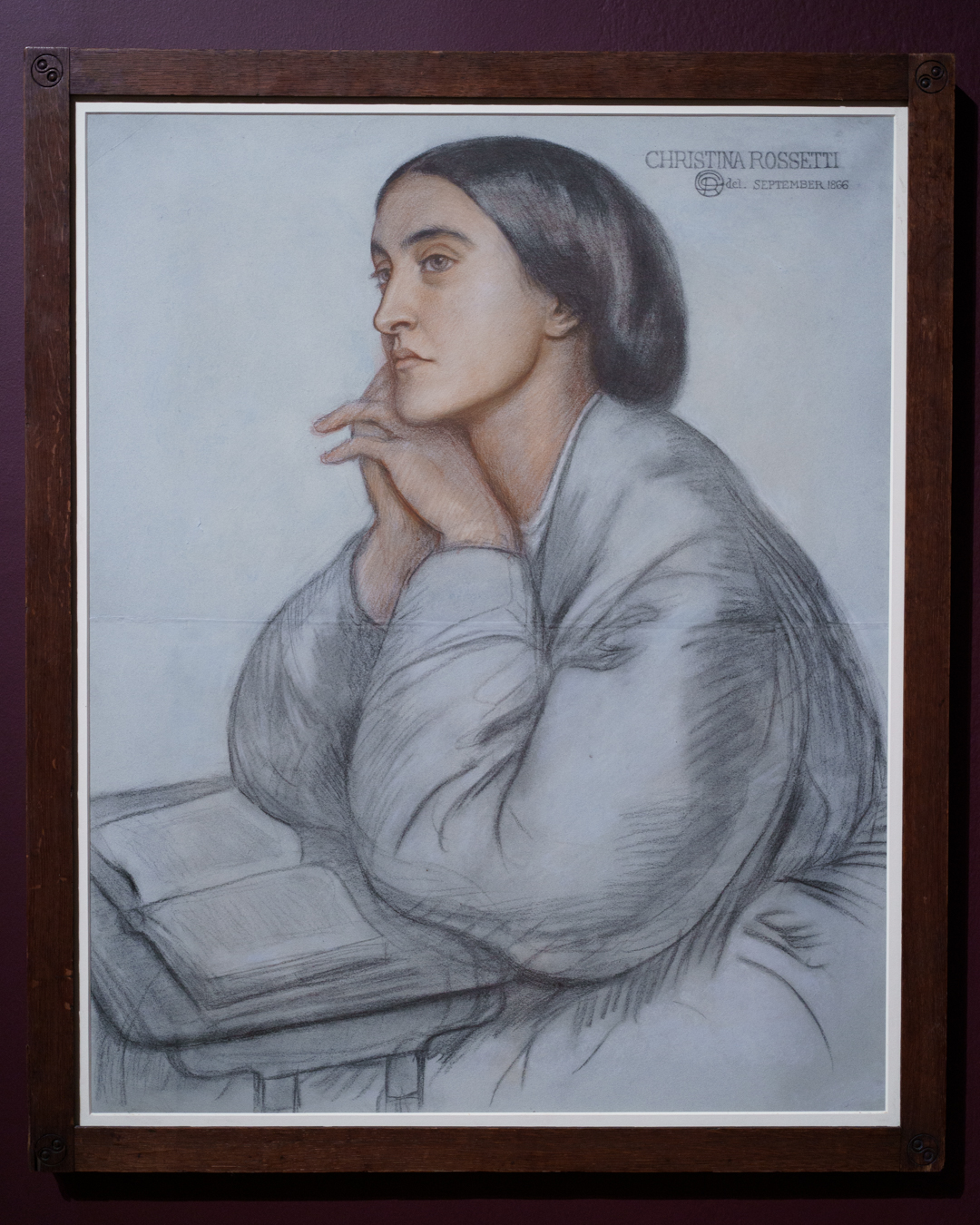

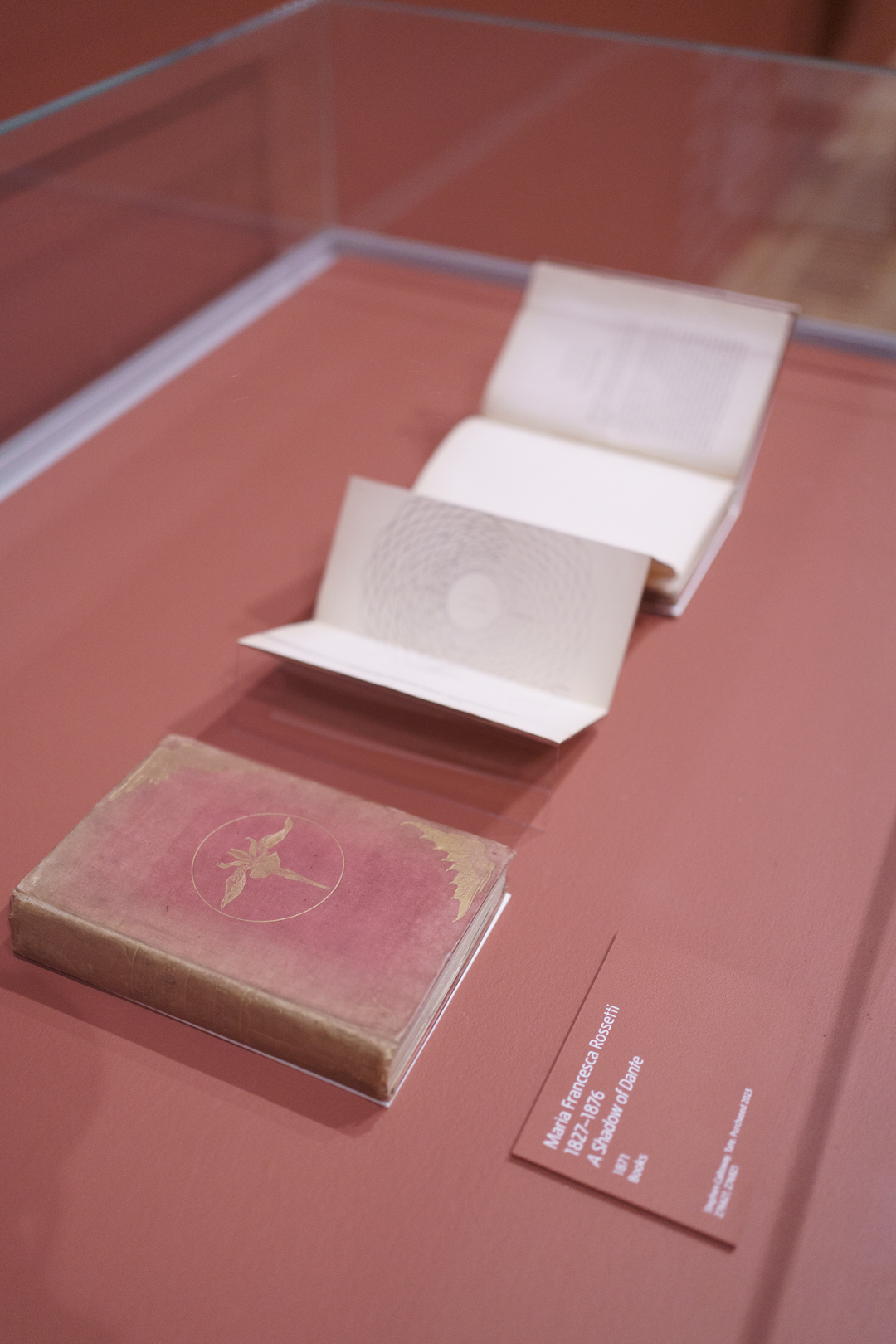

Unfortunately, one learns almost nothing about the pious Maria Francesca Rossetti; Christina receives a good headstart with her poetry recited via sensors on the floor; and William Michael is largely unrepresented after his role in forming the PRB until revived at the end by his anarchist children who launched The Torch journal between the ages of 13 and 16.

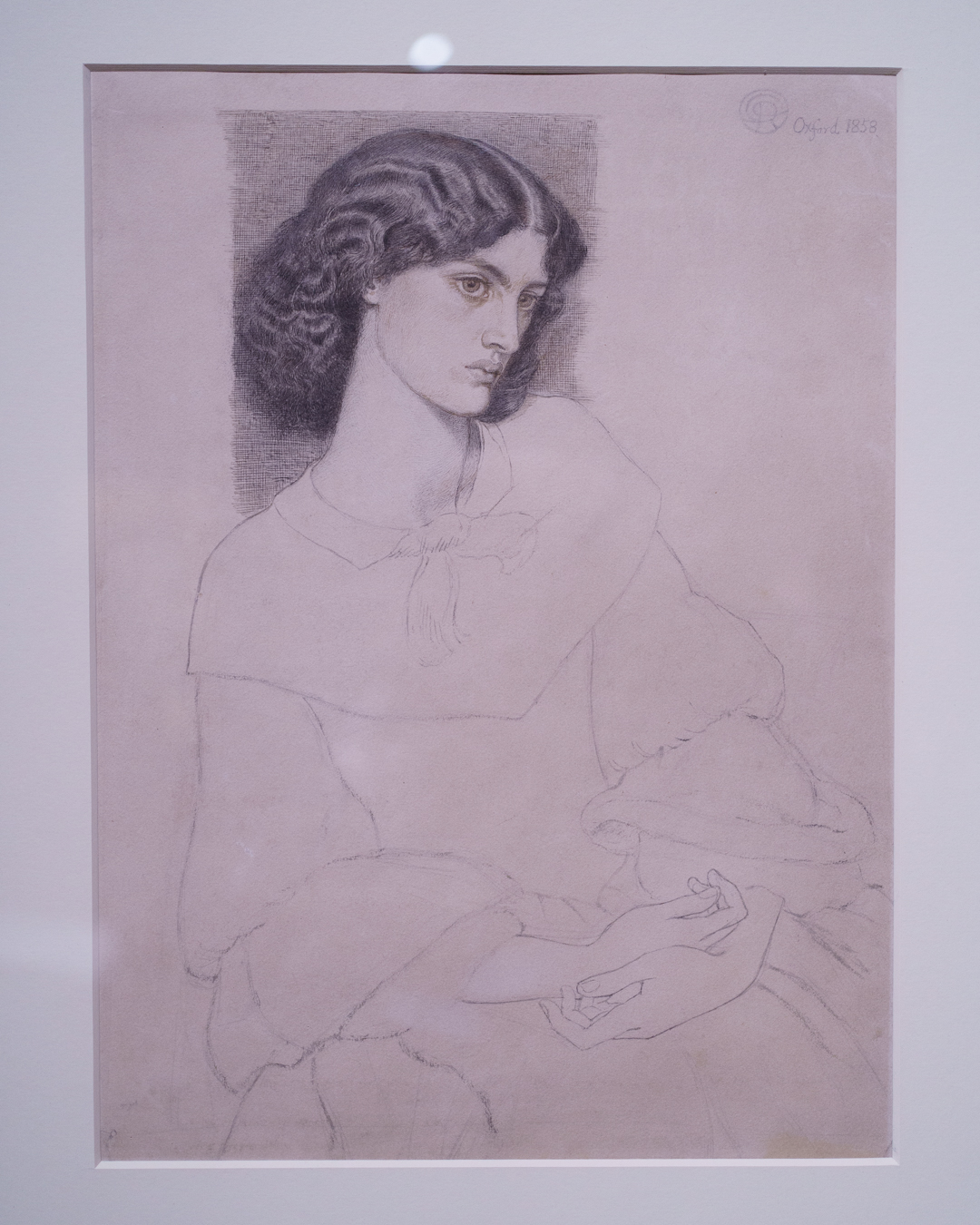

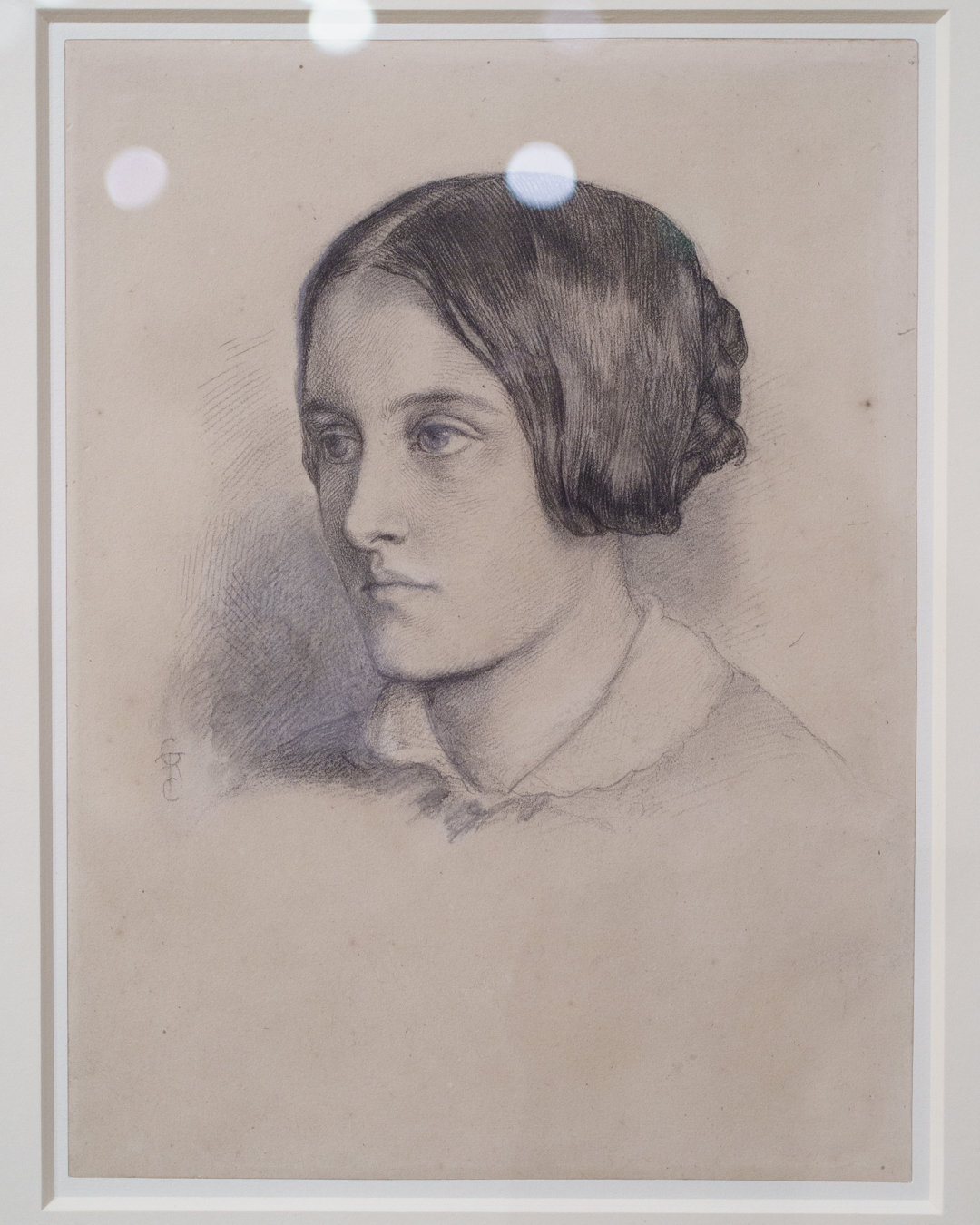

The re-evaluative potential of the largest gathering of Elizabeth Siddal’s works also loses its power from being paired with her husband’s similarly themed works; the aim was to show how she influenced Gabriel, rather than the opposite. They should have received their own room to properly showcase her idiosyncratic voice and character.

Lastly, a significant portion of reunited drawings relating to The Beloved (‘The Bride) (Tate) in one of the most visually impressive rooms were in fact facsimilies; the over-reliance on facsimilies elsewhere was equally irritating. Thankfully, the striking drawing of Fanny Eaton was original and held its visual power in my mind well beyond the exhibition.

Regardless, this show succeeds very well in delivering the most spectacular array of Gabriel’s work to date and is a privilege to visit.

The Rossettis runs until 23 September 2023 at Tate Britain, London, https://www.tate.org.uk

Leave a comment