Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.

The above is the opening sentence to Paul Klee’s Creative Confessions, a critical text written in 1920 that reflects on the artist’s thinking and creative processes. He sees the visual piece as a record of movement, a journey through unploughed fields, rivers, fog, a “flash of lightning across the horizon.” The lines and streaks of colour in a creative work are analogised as features of the visible world. Along the way we even encounter a companion who joins us in the form of a converging line, but differences cause us to move independently, and our personalities and excitement during the journey are shown by the “expression, dynamism, emotional quality of the line.” There is also an intense focus on time, during the creative process and in the process of contemplating a piece of art. By the end of the text, Klee encourages the viewer to “value such country outings”, to have a “change of air” from the dull working day, to inspire your imagination – “to fancy for a moment that you are God” – and to nourish your mind with new ideas and insights, or “new sap” as he calls it.

The ‘Gradation’ room, Klee’s own painterly conception. Image via www.ikono.org.

With 17 rooms to appreciate, Tate Modern has presented a chronological exhibition of this deeply curious artist, from 1911 when he began numbering his works, to his death during the Second World War in 1940.

The EY Exhibition: Paul Klee – Making Visible begins with a timeline of the artist’s life – annoyingly, so does the exhibition guide which gives only a little more detail – from his birth in Münchenbuchsee in 1879, his studies at a private drawing school with Heinrich Knirr, marriage to Karoline ‘Lily’ Stumpf in 1906, the series of solo exhibitions which led to his international fame, to his diagnosis with the incurable degenerative illness scleroderma in 1935. The latter half of his life was closely linked to the political and economic situation of Germany, having moved into an apartment in Munich with Lily the same year they married.

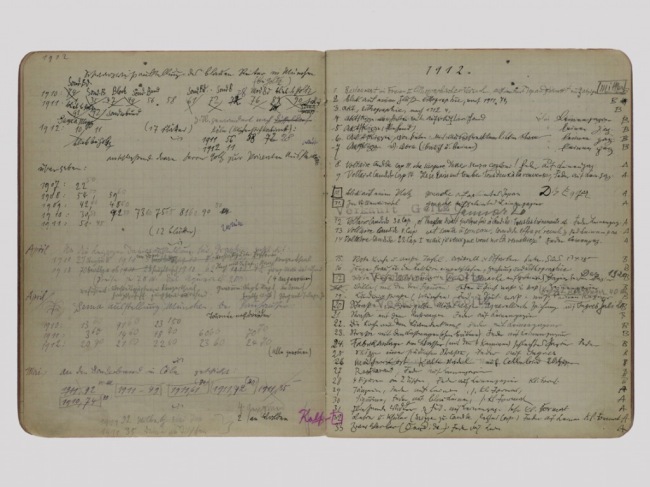

In this first room lies two notebooks with almost identical covers: facsimiles of his ‘oeuvre catalogue’ and his teaching notes from his professorship at the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany. The ‘oeuvre catalogue’ lists his paintings from the year 1911, noting the year they were made, number, title, and even medium and owner of each work where applicable. Having had no previous teaching experience, his notes were very well thought out, some eventually making it into his Ways of Nature Study (1923).

The ‘oeuvre catalogue’. Image via www.tate.org.uk.

The paintings exhibited in the exhibition begin from 1912, during his involvement with artists associated with the Blaue Reiter Almanac, such as Kandinsky, August Macke and Franz Marc. These artists helped the struggling Klee to develop a personal means of expression and encouraged a free use of colour. Other influences were drawn from expressionism and cubism. His early works were very much rooted in the visible world, such as Group of Houses (1912), but abstraction and colour eventually feed into the main composition – Flower Bed (1913).

As you progress through the rooms, the forms become much more ambiguous – you tend to only realise what the paintings are about by looking at their titles. In many cases they follow a certain trend; the subjects of his titles tend to stick out of the compositions like sore thumbs. Fire at Full Moon (1933) is just one of several such works, rendering a yellow circle for a moon in the top-left corner while a deformed bright red cross represents a campfire.

Paul Klee, Fire at Full Moon, 1933. Image via www.elcomercio.com.

We learn of his ‘oil-transfer’ method which allowed him to trace his drawings in oil paint, before being turned into another set of watercolour paintings, the earliest of which – Aerial Combat (1920), Memorial to the Kaiser (1920) and Christian Sectarian (1920) – are shown to us consecutively; they are numbers 2, 3 and 4 in his ‘oeuvre catalogue.’

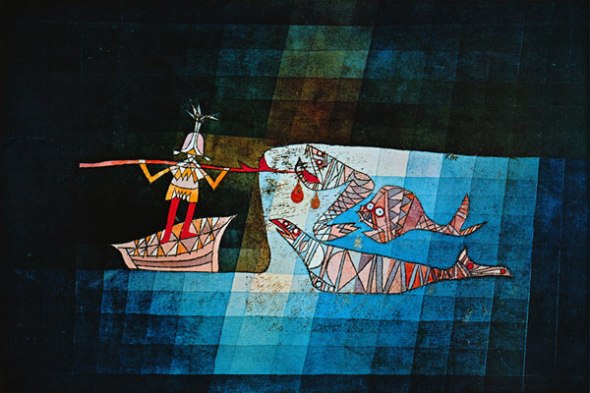

His gradation paintings are wonderfully animated, using only the varying tones and hues to create an illusion of movement, such as the swimming Fishes in the Deep (1921) or the spinning Suspended Fruit (1921). This style of painting was invented when he first arrived at the Bauhaus in January 1921, and he went on to develop it further, including mounting the works on coloured paper. I particularly admired the convincing, yet gradated, spotlighting effect in Battle Scene from the Comic-Fantastic Opera ‘The Seafarer’ (1923).

Paul Klee, Battle Scene from the Comic-Fantastic Opera ‘The Seafarer’, 1923. Image via www.penhook.org.

Klee was particularly well-known for his ‘magic squares’ – Static-Dynamic Gradation (1923) – paintings that had a certain freedom from the constraints of Russian geometric constructivism, but he also had a fascination with still-life painting. Works such as Flowers in Glasses (1925) show his concern with visible appearances while merging his own fascinations into the depicted subject; in the example the flowers oscillate between an obvious depiction of the real thing and a near-abstract surface of colourful forms.

By the late 1920s, Klee had reached a highpoint in his career. He began experimenting more, combining drawing with his own form of spray-paint. Threatening Snowstorm (1927) shows his use of this new technique. His experimentation included pointillism, first hinted at by his landscape of a Seaside Resort in the South of France (1927) before going on to merge it with abstraction in Dancer (1932).

Paul Klee, Dancer, 1932. Image via www.posterlounge.de.

As the Second World War was on the verge of outbreak, the themes and titles of the artist’s work began to reflect the events in Germany. Taking inspiration from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s epic Faust, in which the central scene is when the hero Heinrich Faust makes a pact with the Devil, Klee’s later works depict supernatural interventions into the earthly realms. Earth Witches (1938) and Forest Witches (1938) take calligraphic forms, laughing and smirking at the viewer. In 1935, he was diagnosed with an incurable degenerative illness, scleroderma, and these works may have been influenced by his declining health. Despite his illness, his last two years were rather productive, and it is here when we see his abnormally large Rich Harbour (1938) as well as his last ever painting, Twilight Flowers (1940).

Paul Klee, Rich Harbour, 1938. Image via www.waldemar.tv.

This exhibition is a fine example of how documentary evidence such as Klee’s ‘oeuvre catalogue’ can help create opportunities for detailed artist retrospectives. It allows us to examine the artist’s journey and ways of thought, charting his experiences and potential influences. His experimentation reminds me a little of Leonardo da Vinci, especially in the following passage by the German-American expressionist painter Lyonel Feininger and his wife Julia in their Recollections of Paul Klee (1945), which sounds a bit like Giorgio Vasari’s description of Leonardo approaching his famous Last Supper (1494-98) mural in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan:

For hours he would sit quietly in a corner smoking, apparently not occupied at all – but full of inner watching. Then he would rise and quietly, with unerring sureness, he would add a touch of colour here, draw a line or spread a tone there, thus attaining his vision with infallible logic in an almost subconscious way.

The EY Exhibition: Paul Klee – Making Visible runs until 9th March 2014 at Tate Modern, London, www.tate.org.uk.

Leave a comment